Last updated: December 13, 2023

Article

Water Quality in Southwest Alaska

NPS/Paul Gabriel

Katmai and Lake Clark national parks and preserves were created, in part, to protect high-quality habitat for salmon. Cold water is a key habitat requirement, but exactly how cold depends on the salmon species, population, and life stage. To address this complexity, the State of Alaska uses several freshwater temperature thresholds that align with the upper end of the range of temperatures tolerated by salmon at specific life stages. According to these thresholds, water that supports spawning or incubating salmon may not exceed 13°C, and water that supports migrating or rearing salmon may not exceed 15°C. Also, water may not exceed 20°C at any time, if it supports aquatic life. In 2019, water temperatures in Katmai and Lake Clark national parks and preserves exceeded all of these thresholds.

Findings

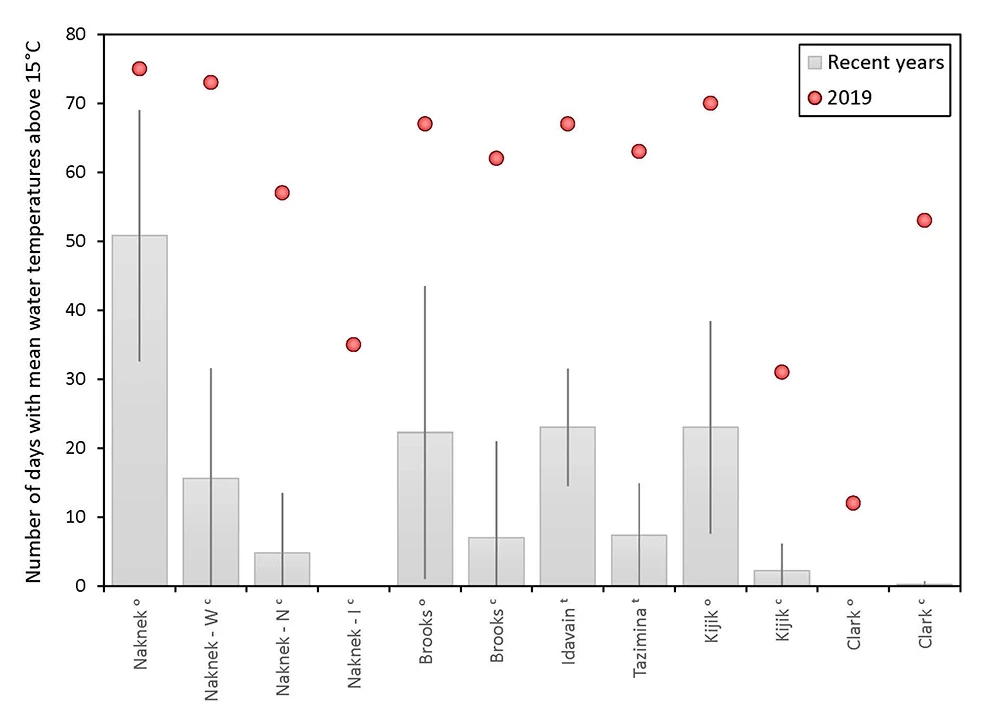

Air temperatures in Alaska during 2019 topped previous records for the warmest year. Water temperatures also broke records in many locations. For example, 12 monitoring sites that support salmon migration and rearing had the highest number of days where water temperatures exceeded the State of Alaska’s defined 15°C threshold (Figure 1; for all sites, summer encompasses June 1 through October 1.).

Methods

The Southwest Alaska Network (SWAN) uses several approaches to monitor water temperature, ranging from year-round measurements at targeted locations to once-a-year measurements at randomly selected sites. These measurements rely on various types of equipment located in different types of habitat. For example, moored arrays are deployed at seven lake center sites, where they record temperatures experienced by juvenile salmon while rearing. Likewise, multi-parameter sondes and pressure transducers are deployed, respectively, at two and four lake outlet sites. There, they record temperatures experienced by migrating smolts and spawners. In all, SWAN monitors temperature at more than 180 sites distributed throughout three parks.

References

Sauter, S. T., J. McMillan, and J. Dunham. 2001. Issue Paper 1: Salmonid behavior and water temperature. Prepared as part of US EPA Region 10 Temperature Water Quality Criteria Guidance Development Project. EPA-910-D-01-001.

Richter, A. and S. A. Kolmes. 2005. Maximum temperature limits for chinook, coho, and chum salmon, and steelhead trout in the Pacific Northwest. Reviews in Fisheries Science 13:23–49.