Last updated: May 29, 2024

Article

“Wake Nicodemus:” Archeology at the Thomas Johnson/Henry Williams Farm

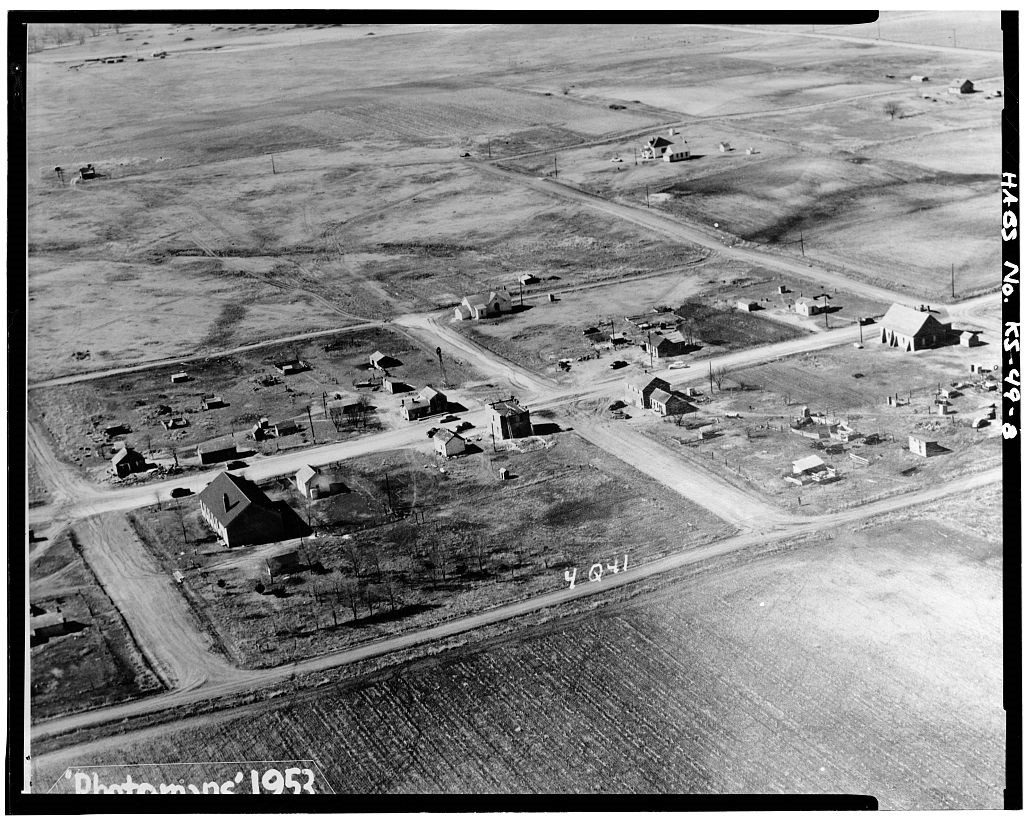

Historic American Building Survey Collection. Library of Congress.

Fleeing from new forms of oppression that were emerging in the post-Reconstruction Era South, a group of African American settlers established the community of Nicodemus on the windswept plains of Kansas in 1877. From this time onward Nicodemus became a community of primarily Black farm families.1 Nicodemus National HIstoric Site preserves five remaining historic structures—First Baptist Church, African Methodist Episcopal Church, St. Francis Hotel, the First District School, and Nicodemus Township Hall. Students, under the guidance of Dr. Margaret Wood of Washburn University, conducted archeological testing on the Thomas Johnson/Henry Williams farm site (14GH102), located approximately four km north of Nicodemus, Kansas. The objective of this research was to identify and explore archeological sites related to the settlement period and early occupation of Nicodemus.

Historic American Buildings Survey Collection, Library of Congress.

A Brief History of Nicodemus

In the summer of 1877, the Reverend M. M. Bell and his congregation watched cautiously as a white man, W. R. Hill, stepped to the podium of a small African American Baptist church near Lexington, Kentucky. Hill began to speak. The “Great Solomon Valley of Kansas,” he said, “offered the opportunity of a lifetime if they were brave enough to seize it.” The area, he extolled, was blessed with rich soil, plentiful water, stone for building, timber for fuel, a mild climate, and a herd of wild horses waiting to be tamed to the plow. Government land was available for homesteading and Kansas was a state known for its liberal leanings, especially in regard to the rights of blacks.2

As the early settlers to Nicodemus were later to discover, Hill’s claims were wildly exaggerated. In truth, Graham County was relatively unsettled in 1877 precisely because it was not as conducive to agriculture as Hill had claimed. Many considered the area, with an annual rainfall of less than thirty inches, too dry for farming. No timber was available for building or fuel except for a few stands of softwood along the rivers or streams. Transportation was a problem as well. No railroads or stage lines served the area in 1877 and the nearest towns were more than a day’s ride away.3

Nonetheless, 350 people from the Lexington area paid a five-dollar fee and signed up for the September migration to Kansas. Winter was only a few months away and few had sufficient capital to see them through the cold season. These concerns, however, were overshadowed by the desire to build a future for themselves and their children in a land where a person was judged by the quality of their character and not by the color of their skin. Traveling on trains, in wagons and, sometimes, on foot, they arrived in Nicodemus on September 17, 1877. The barren landscape surrounding Nicodemus was a stark contrast to the wooded hill country of Kentucky. Fifty of the most disillusioned returned to eastern Kansas the following day, while those that remained set about making preparations for the coming winter. Between the spring of 1878 and 1879 over 225 additional migrants from Kentucky and Mississippi arrived in the colony. Before long the settlers had established themselves on 70 farms scattered across the landscape.4

The settlers’ most immediate need was housing. Faced with a lack of timber, transportation and money, the dugout was the only realistic option for shelter in the area. As soon as basic shelters were constructed, colonists began to break ground for gardens and crops. Whole families–men, women and children–participated in the backbreaking task of breaking the prairie. In spite of all of this labor, the first crops failed. Determined to make their efforts pay off, farm families continued to turn and cultivate the land. In the spring of 1879 the average farm had 7 acres or more in cultivation.5

Nicodemus experienced steady growth and prosperity throughout the first half of the 1880s. The expected arrival of the railroad and the financial success of farmers in the area brought an influx of capital and businessmen into the community. Unfortunately, Nicodemus’s golden age was short lived. In 1887, the railroad failed to fulfill its promises and bypassed Nicodemus in favor of a small town a few miles to the southwest. The impact was devastating for the burgeoning community. The failure of commercial development in the town was coupled by a series of droughts lasting from the late 1880s until the mid 1890s that besieged the farm families living in the surrounding township. Given these challenging conditions, many farmers lost or sold their property in this period. Between 1885 and 1900 land ownership rates in Nicodemus Township plummeted from 96 percent to 54 percent. In this same time period the number of farms in the Township fell from 70 to 48. After 1900, however, farmers began to recover from these catastrophes and both land ownership and farming conditions improved.

Thomas Johnson/Henry Williams Family

Thomas Johnson, one of the earliest settlers to Nicodemus, homesteaded a piece of land just outside of the town of Nicodemus in 1878. He filed his claim in 1885 and received the patent for his property in April of 1889. He and his extended family farmed the land and adjacent properties for over a decade. Johnson’s grandson, Henry Williams continued to farm Johnson’s original claim until the middle of twentieth century. The property is still in the hands of a close family member. This farm became the focus of archeological investigations. Johnson’s properties formed an L-shaped area of land in Section 23 of Nicodemus Township. His property was bounded by the properties of his sons, daughters, and son-in-law.6

Thomas Johnson brought his extended family with him including his wife Zerina; his son Henry, daughter-in-law Mary, and granddaughter Ella; his daughter Ella (who also may have been known as Ellen); his daughter Emma Williams, son-in-law Charles Williams, and an adopted grandchild Mack Switzer; his widowed sister-in-law Mary Johnson, nephew Joseph, and great nieces Liz and Clarina Johnson.7 In all, 13 people made up the Johnson/Williams families in 1880. While the extended family probably migrated as a group, they are listed as five distinct households in the census records. Maps of the township, however, show only a single dugout on the properties owned by the Johnson and Williams families. Whether they lived together or in distinct households is unclear.

In 1885, Thomas, Henry, and Joseph Johnson and Charles Williams each worked 160 acres, valued at $2700,8 according to Kansas State census records. Collectively, the family owned $85 worth of machinery, 4 milk cows, 9 head of cattle, 2 pigs and 1 horse. Like other farmers in the area, the Johnson and Williams families grew mostly corn and wheat, although some sorghum and hay for feed was under cultivation as well. Each farm also had a half an acre planted in potatoes and, collectively, the women of the family produced six hundred pounds of butter.

In 1886, A.G. Tallman of the Western Cyclone newspaper visited the Thomas Johnson farm. In his description, Tallman suggests that the extended family operated as a common unit, sharing equipment, pooling labor, and diversifying crops among the various farms.

A visit to the farm of Thos. Johnson is enough to encourage the homesick farmer of any state. He and his children, all with families, own a tract of land of a thousand acres about one fourth of which is under cultivation. He has about 60 fine hogs and the whole family owns a large herd of cattle and several fine horses. They have recently bought a twine binder and are in the midst of harvest. When you make a visit to Mr. J’s farm do not forget to look at Mrs. Johnson’s chickens and ducks.9

The collective nature of this farming venture is further suggested by information from the agricultural census. Henry Johnson planted over 37 acres in corn and wheat, while Joseph Johnson owned a barn and Henry Williams had invested in expensive farm machinery. Each family seems to have specialized in some sort of production with little duplication of effort across the family groups. Oral history and agricultural census data suggests that Thomas Johnson lived on his property in a dugout near Spring Creek. The flowing stream provided much-needed fresh water for animals and could be used for various household needs, food, and religious rituals. Thomas Johnson was not only a farmer and a Civil War veteran; he was also a deacon in the Baptist Church. When he moved to Nicodemus he organized a congregation and held revival services in his dugout. Spring Creek became an ideal location for baptism ceremonies.

During the late 1880s the entire region experienced a series of droughts that devastated family farms. The difficult environmental and economic times weighed heavily on the Johnson and Williams families which were compounded by additional setbacks when Joseph Johnson lost his barn, feed and many of his animals to a grass fire in 1887.10 The combined effects of the drought and fire led Thomas Johnson and most of the extended family to sell their claims in 1889. The only family from the original Johnson/Williams group to remain at Nicodemus was the family of Charles Williams. By 1900, Emma Williams was a widow raising four children. Her sons Henry and Neil worked on the land.

Although the property of Thomas Johnson passed through several hands it ultimately ended up in the ownership of the Midway Land Company of Wyandot County, Kansas. The land was corporately owned until 1906 when Henry Williams, son of Charles and Emma Williams and grandson of Thomas Johnson, purchased the property. Henry Williams and his wife Cora raised six children on this property. They worked and lived on this land until the middle of the twentieth century.

Midwest Archeological Center, NPS.

Archeology at the Thomas Johnson/Henry Williams Farm

Constructed approximately 130 years ago, dugout and sod structures associated with the settlement of Nicodemus have been obscured by the passage of time and the powers of nature. Dugouts were constructed with hand tools in the slope of a hill or a stream bank. Excavations were carved into the slope and then covered with a roof of poles, brush, and enough dirt to keep out the rain. A fireplace built into the earthen walls served for heat and cooking. The front wall and entrance were constructed with scrap lumber, stone, or sod. If glass could be obtained, a window that provided light and ventilation was included.11 The floor and walls of the dugout were made of packed earth that was sometimes plastered with a clay-like mixture of water and a yellow mineral native to the area.12 Dugouts were seen as a temporary solution, however, and over time these modest homes were replaced by sod and frame houses.

Several depressions were noted during a 2006 survey of the Henry Williams farm property . These were possible features associated with Thomas Johnson’s early occupation of the property. Field school students excavated 11 shovel test pits and 19 one-meter square test units, and were successful in identifying 2 structures and 17 associated features. The construction materials, size, and artifacts present suggest that one of the structures was a hybrid semi-subterranean dug-out/sod-up house The other major structural feature was a root cellar.

Located close to the creek and on a gently sloping area of land, the domestic structure is apparent as a series of indistinct mounds and a slight depression. This structure also has a C-shaped footprint and is oriented southwest to northeast. A 2 m wide doorway faces southeast. The center area of the C-shape is only slightly lower than the surrounding mounds. At its greatest extent the house measures 12 m in length (southwest to northeast) and 10 m wide.

Excavation revealed a limestone wall of regularly shaped soft limestone that extends 1 m into the ground. limestone is available from nearby quarry sites. Only the north wall of the area tested, however, appeared to be composed of limestone. The west (rear) wall of the structure was covered with a white plaster.

Only 151 nails were recovered from the excavations. This suggests that the walls of the house above ground surface were constructed from sod blocks rather than wood. The nails were probably used to secure window frames (window glass n = 76) and tar paper. The floor of the house was finished with a hard-packed white magnesia made of ground limestone to keep down dirt and insects.

Immediately above the floor of the house is a deposit of fine ashy soil associated with the last use and abandonment of the house. This layer contained a high frequency of material culture; over 495 artifacts representing 44 percent of the assemblage were recovered from the interior of the domestic structure. The domestic use of this building is clearly indicated by the types of artifacts recovered. Architectural artifacts include 98 wire nails and four cut nails, 16 pieces of window glass, a knob and a rivet. Personal and clothing items included 2 beads, 5 safety pins, a collar stud, 23 buttons, 2 snaps and a fragment of a shell hair comb. A variety of food related artifacts including three canning jar fragments, a spoon, mixing bowl sherds, tea ware, portions of a platter, tea pot, tea cups, and a saucer were present. All of the ceramics were a general whiteware/ironstone or porcelain type. A marble, doll parts, two white clay tobacco pipes and one whiskey bottle fragment also came from this layer. There were several diagnostic items in this layer including four coins (three pennies, one dime) dating to 1890, 1900 and 1904. We also recovered two pieces of Black Bakelite or plastic comb fragments. Bakelite was produced beginning in 1907. Finer forms of plastic that were commonly used in personal grooming products like combs and toothbrushes were not produced until 1915. It is not clear whether the comb fragments are Bakelite or plastic.

The diagnostic materials suggest that this semi-subterranean house was probably occupied as late as 1915. The abandonment of the structure probably occurred when the nearby frame farmhouse was built around 1919. The last occupants of this home were probably Henry Williams (grandson of Thomas Johnson), his wife, and six children. Excavations did not clearly reveal when the house was constructed. The presence of red transfer print whiteware (circa 1829-1859) in the lower levels of test units placed outside the north limestone wall of the house hint at either an early occupation date (Thomas Johnson) or the use of old ceramics by the inhabitants of the home.

Historical sources, however, strongly point to the likelihood that this house was built by Thomas Johnson around 1877. Agricultural census data indicate that Thomas Johnson had a spring on his property that he used for both domestic and agricultural purposes. Only 50 m from the ruins of the home are the remains of a pitcher pump marking the location of a natural spring. While natural springs are not unheard of in this area, they are relatively rare.

The root cellar is the most obvious feature on the site, consisting of a C-shaped depression cut into the sloping landscape. At its greatest extent the root cellar measures 7.7 m in length (SW to NE) and 6.1 m in width (SE to NW). These measurements include the soil that was probably mounded on the exterior of the structure to provide insulation and support. A doorway measuring approximately 2 meters wide is located along the south side of the structure. Mounds on either side flank the doorway. These mounds define the outline of the C-shaped building. In the center of the C-shape is a significant depression that is approximately 1 m deeper than the surrounding landscape. The packed dirt floor of the structure was situated approximately 1.4 m below the surface.

The walls of this structure were plain, untreated soil and it appears that a simple wood frame (possibly covered by sod) made up the roof. Partial excavation of a test trench revealed a stain that defined the north and east walls of the feature.

Artifacts from the bottom-most levels suggest the function of the structure. Seventy eight percent of all excavated food related material was identified as fragments of glass home canning jars. Several clusters of peach pits were also scattered across the floor. Rough, simple iron door hinges, a few bottle fragments, and faunal remains from small mammals, including mice and weasels, were recovered from the floor.

Several stains extending horizontally into the wall. These stains occurred in groupings and were irregular in size and shape. The stains that make up each grouping however are level relative to one another and probably represent shelves and bins that were built into the wall of the root cellar. The irregularity of shape and size of the stains suggest that the people who constructed the root cellar used some of the scarce, but locally available, wood from trees along the banks of the nearby Spring Creek. Although good diagnostic material was not present in the root cellar, it was probably used in association with the nearby house, and abandoned around the same time.

Historical Use of Local Resources

The Johnson and Williams families used locally available materials very intensively. Limestone blocks from a nearby quarry and sod from nearby fields were the primary components of the house. Shelves, bins, floor supports, and roofs were made from branches of nearby trees. Even the magnesia that was ground into the floor was primarily made of local soft limestone. A closer look at the faunal and floral assemblage reinforces the general impression of self-reliance. Both the root cellar and the domestic structure yielded a fair amount of faunal material, but each tells a slightly different story about the subsistence strategies of those who lived on the site.

Surprisingly, the assemblage contains a large number of wild mammal bones and a relative scarcity of domestic mammal bones. We had expected to recover a greater quantity of domestic mammal bone, given the fact that we were working on a farm site located in a region of the country known for its livestock production. This, however, was not the case. While wild mammals made up 37 percent (n=148) of the faunal assemblage, domestic mammals only constituted four percent (n=19) of the assemblage. Bird remains contributed 35 percent (n=141) of the faunal material, although this number probably over-represents the contribution of fowl to the diet. Eighty eight percent (n=124) of the bird related material was eggshell. Also a surprise, frog bones made up 13 percent (n=53) of the faunal assemblage.

Thirteen bones (9 percent) of large domestic mammals were identified. Seven of these were pig bones and two were cattle bones. The remaining four bones were only identifiable as large mammals. Three of the large mammal artifacts were dental molars and portions of jaws. All of these were recovered from the root cellar. Analysis of tooth eruption and tooth ware patterns indicates that all of the identifiable pig bones in the assemblage came from young individuals.

While the pig remains suggest that juvenile individuals were being butchered, cattle remains suggest that older individuals were being selected for slaughter. The single cow tooth recovered was heavily worn.13 The family who lived on this farm may have only slaughtered older cows who had outlived their use as dairy cattle. The fact that most of the large mammal assemblage was made up of jaw and skull fragments suggests that the residents were consuming portions of the animal with less meat and were selling the rest.

Thirty seven percent (n=148) of the faunal assemblage was comprised of small mammals; however, the majority of the specimens (n=123) came from the root cellar. Identified species include weasel, marten, possum, skunk, rabbit, gopher, squirrel and rat. Many of these small mammals may have been attracted to the food, or hunted other mammals in the root cellar. Some of these animals, however, may have been hunted or trapped by the family that lived on the site.

Spring Creek flows through the Thomas Johnson/Henry Williams Farm site and many visitors to the site indicated that they remembered fishing near the farm. Undoubtedly the creek would have been a good source of supplementary food. Yet, we found no fish bones or scales. This may be due to our small sample size or our recovery methods. We did however find a large number of frog (amphibian) bones and a single crayfish element. A total of 54 frog bones were recovered from the site. These constituted 13 percent of the faunal assemblage. The floor and occupation levels of the root cellar (Feature 1) yielded the most amphibian bones (n=52, 96% of amphibian assemblage). The frog bones represent only four lower skeletal elements including: the ilium, femur and tibiofibula, and the urostyle. The overrepresentation of these elements suggests that the residents of the farm were preparing frog legs. Indeed, the frog skeletal elements show signs of butchering and femurs are consistently cut across the acetabulum. The abundance of frog legs in the root cellar feature suggests that these delicacies may have been canned.

Residents of this farm were utilizing a large portion of their natural environment. While they were farmers growing crops and raising livestock for sale, there is only sparse indication that they consumed many of these resources themselves. Research on other Kansas homestead sites is revealing a similar pattern on farms located in risky marginal environments like those around Nicodemus. Residents appear to rely heavily on local resources while selling their produce and livestock outside the community.

It would be simple to chalk these patterns up to rural poverty. While the farm families in and around Nicodemus were not wealthy by any stretch of the imagination the rest of the assemblage indicates that they decorated their homes with a sense of style. The presence of tea wares, decorative vases and candy dishes all suggest that these are not necessarily people living on the edge. A variety of decorative buttons suggest fashionable clothing, and toys for children also show some level of disposable income.

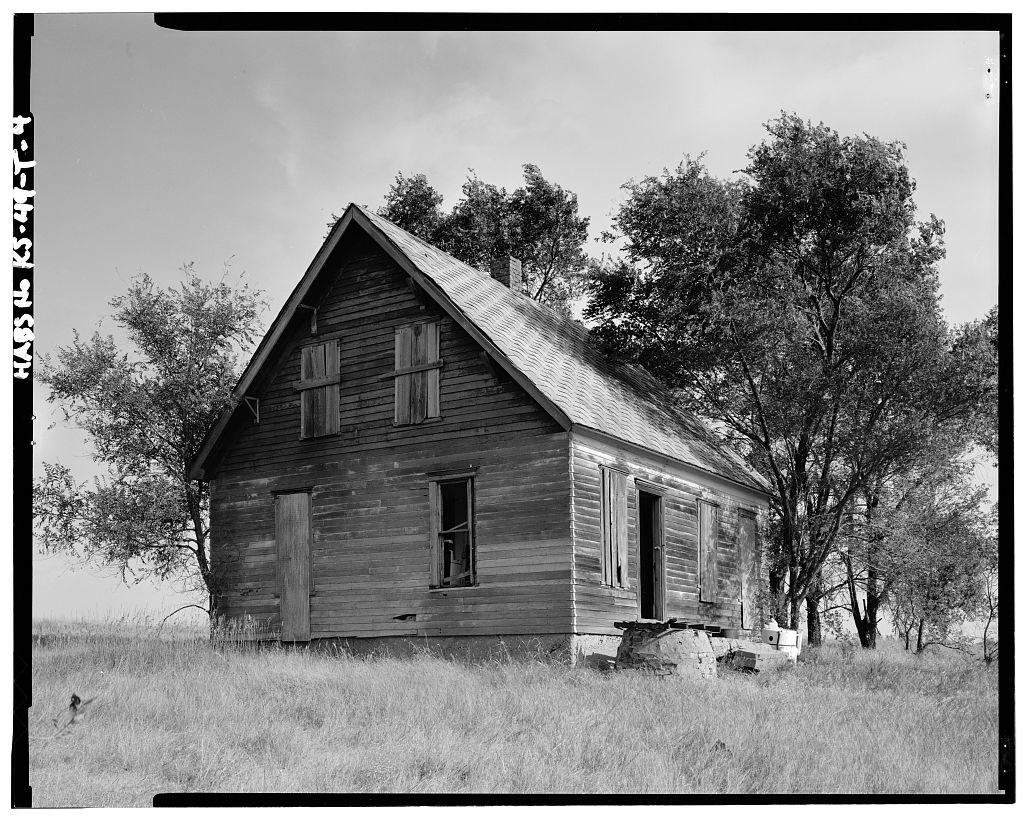

Historic American Buildings Survey Collection, Library of Congress photo.

Family and Landscape

The results of both archeological and historical research on the Thomas Johnson/Henry Williams farm site (14GH102) reveals a story of ingenuity, pride and the struggle to survive in a harsh and punishing environment. The material remains of this site give us glimpses into the web of kinship and community that link not only people and places but also the present and the past at Nicodemus. For the generations of people who lived in and around Nicodemus, the central ingredient of collective independence and autonomy was, and continues to be, kin based interdependence. It is this interdependence that has allowed this community to survive both socially and economically.

Like Thomas Johnson, the first group of immigrants to Nicodemus was made up of a handful of large extended families. Most of these families had been slaves on a single plantation in Georgetown and, thus, had close familial and personal ties. These family names persist in the area today. As extended families established themselves on the land, they sought to file multiple claims, each in the name of a different head of household, to maximize continuous acreage owned and controlled by the family. The Johnson and Williams families clearly utilized this strategy by filing claims to an entire section and portions of two adjacent sections. By dividing up the tasks, equipment, and resources necessary for farming they may have hoped to minimize the hazards associated with this risky endeavor. This web of family support, however, was not enough to overcome the fickle nature of the environment of western Kansas. A series of droughts and other catastrophes drove most of the Johnson family off the land. Only Emma (Johnson) Williams and her family remain on their original claim in Nicodemus after 1889.

Speaking of the environmental and economic tragedies of the late 1880s and early 1890s, Lula Craig indicated “it took many years for families to get back the land they lost.” Clearly, the Williams family considered this land their own and sought over time to reclaim it. Henry Williams settled on his grandfather’s original claim with his own wife and family, working the land immediately adjacent to his mother’s land.

Conclusions

The connections between family and land are strong in Nicodemus. On the Thomas Johnson/Charles Williams farm we see the sacrifice and ingenuity that African American families made in order to achieve independence. We also see the links of family bonds and filial responsibility that cross generations. This property was not only claimed by multiple generations of the same family, it also placed family members on the landscape in such a way that they could be near each other and support one another. Thomas Johnson and his extended family settled adjacent properties in order to combine their efforts and struggles in this new and challenging endeavor.

While many of the family members sold their lands, Charles Williams, Emma Williams and their children eventually reclaimed some of the property. Henry Williams may have grown up on this property, living with his parents and grand parents. As an adult, he established his own home, but within close proximity of his widowed mother and younger siblings. On this one relatively small piece of land we see the material remnants of kinship and family that linked people through time and space.

The farmers of Nicodemus bought economic independence and autonomy, by ingenuity and the skillful use of locally available raw materials. On the other hand, the interdependence of kin relations is powerfully encased in the use of the landscape and the transfer of land over generations. Ultimately, as the people of Nicodemus knew, it was the land and their relationships with others that afforded them their autonomy and freedom.

Endnotes

- Kenneth Hamilton, “The Settlement of Nicodemus: Its Origins and Early Promotion,” in Promised Land on the Solomon: Black Settlement in Nicodemus, Kansas (Washington, DC: National Park Service, Government Printing Office, 1986) 2-34: Kenneth Hamilton, Black Towns and Profit.

- James N. Leiker, “Race Relations in the Sunflower State” Kansas History (2002): 214.

- Daniel Hickman, Notes Concerning The Nicodemus Colony, transcribed by G. A Root, (Graham County History File, KSHS Archives, June 1913).

- Glen Schwendemann, “Nicodemus: Negro Haven on the Solomon,” The Kansas Historical Quarterly 34 (Spring 1968), 14.

- O. C. Gibbs, “The Negro Exodus: A Visit to the Nicodemus Colony” (Chicago Tribune, 25 April 1879).

- Orval L. McDaniel, A History of Nicodemus, Graham County, Kansas (Masters Thesis, Fort Hays State College, July 1950): 126-128.

- Census of the United States, 1880.

- Census of the State of Kansas, 1885.

- A.G. Tallman, “Visit to the Thomas Johnson Farm.” (Western Cyclone, 1 July 1886).

- Lula Craig Manuscript, Folder 5, RHMSD250.5 (University of Kansas: Spenser Library).

- O. C. Gibbs, “The Negro Exodus: A Visit to the Nicodemus Colony” (Chicago Tribune, 25 April 1879).

- Bertha Carter, “Oral Interview,” unpublished field notes, Nicodemus, (May 2006).

- Analysis of select faunal material was completed by Dr. Tanner, Kansas (September, 2006)

By Dr. Margaret Wood, Washburn University