Last updated: November 22, 2017

Article

Mid-Nineteenth Century Celestial Observations at Vancouver Barracks

On the evening of September 9, 1858, Post Surgeon Joseph K. Barnes gazed into the heavens above Vancouver Barracks, then known as Fort Vancouver, and spotted a large comet blazing across Washington's night sky, noting in his weather observation journal, "Comet of first class visible in N.W. 10º above horizon at sundown." Barnes, who would later rise to meteoric heights himself as Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, witnessed what was known as Donati's Comet, one of the brightest comets to be seen in the 19th century. By October, he had submitted a more technical description of the event:

Donati's Comet, also known as the Great Comet of 1858, or by its formal designation C/1858 L1, is noteworthy because it was the first comet ever to be photographed. Named for Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Donati, who first discovered it on June 2nd of that year in Florence, the comet was tracked across the skies by astronomers for ten months. One noted observer, then-Senate hopeful Abraham Lincoln, reportedly sat for over an hour on the front porch of his hotel in Jonesboro, Illinois, on the eve of his third debate with Stephen Douglas, and "greatly admired this strange visitor." The comet was exceptionally bright and visible to the naked eye for many months. By October 16, Barnes noted that the comet was seen for the last time over the post, but it was still visible around the world until March 1859."The Comet - visible upon the evening of [September] 9th 10º above horizon in North West - increased in brilliancy and size throughout the month. Until the 15th it was also visible at 4 a.m. in the N.E. On the 30th the elevation at sundown was 50º length of coma 30º. The nucleus was on the horizon at 9 h. 11 m P.M. at which time the coma had increased in size & brilliancy, extending nearly 50º from west to N.W. with well marked curve in direction of the course of its flight."

Though it might seem peculiar for a surgeon to report astronomical and weather observations, this is not uncommon. Nineteenth-century physicians recognized that a relationship existed between illness and changing weather conditions. In 1818, Army Surgeon General Joseph Lovell mandated that the personal duties assigned to Army surgeons included the observation and recording of meteorological events, and that the surgeon "shall keep a diary of the weather in the form and manner prescribed, noting everything of importance relating to the medical topography of his station, the climate, complaints prevailed in the vicinity &c." The surgeon's weather diary took the form of a monthly "meteorological register," with itemized columns for temperature, precipitation, cloud cover, wind direction, and any other notable remarks. The instructions published in 1844 reminded observers to "examine the heavens at the latest observation, whether there by any Aurora or shooting stars [and] any great numbers of luminous meteors visible."

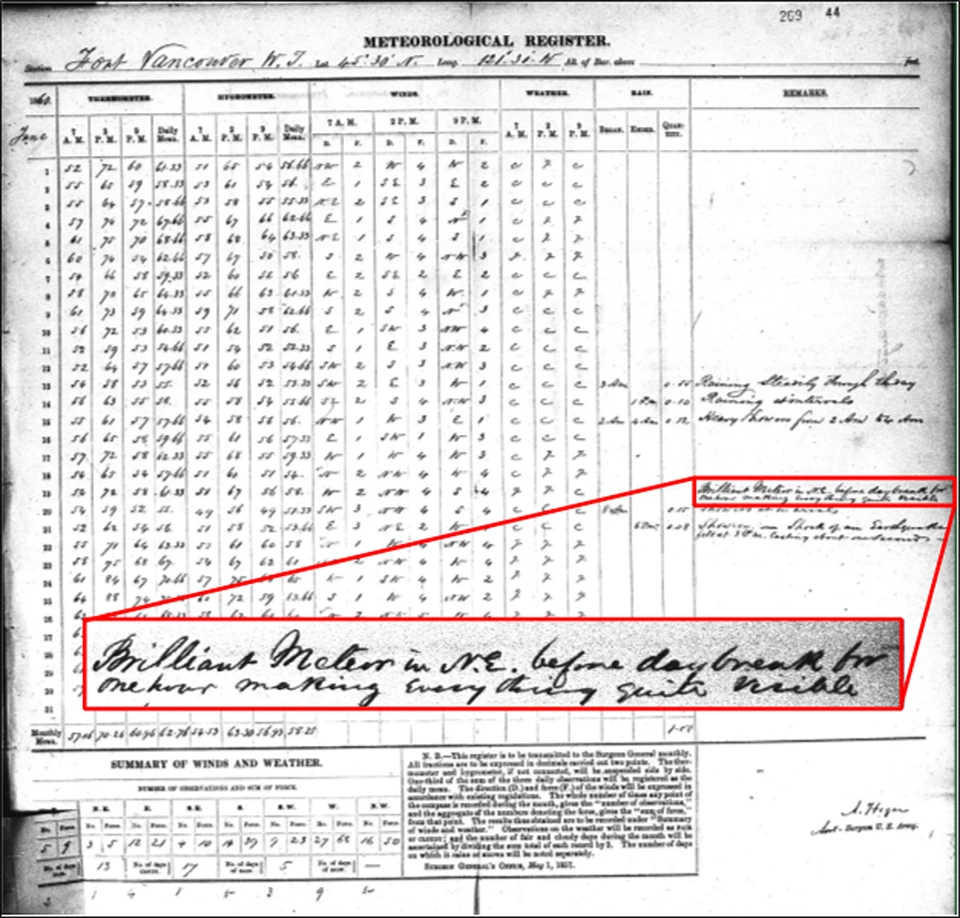

Climatological Records of the Weather Bureau, 1819-1892. National Archives and Records Administration. Publication #T907C, Microfilm Roll #537.

On June 19, 1860, Assistant Surgeon Anthony Heger wrote, "Brilliant Meteor in N.E. before daybreak for one hour making everything quite visible." This sighting was probably not a meteor, as the duration of a true meteor is usually measured in tenths of a second. Instead, this most likely refers to Comet C/1860 M1, which was visible until June 22.

Assistant Surgeon Joseph B. Brown, who had arrived only three days earlier for duty at the post, noted the following entry for July 1, 1861: "Comet visible at Sunset above 45º in N.W." This comet, named the "Great Comet of 1861," or C/1861 J1, was reported to have six tails, although this view is most likely due to Earth's orbit passing within the comet's tail, giving the appearance of streams of cometary material converging towards a distant nucleus. Brown continued to note its presence every day in the register, until finally remarking, "Comet disappearance," on July 19.

On August 23, 1862, Assistant Surgeon Anthony Heger, who had returned to Fort Vancouver from Fort Steilacoom, most likely made a sighting of the Swift-Tuttle Comet (109P/Swift-Tuttle), when he wrote, "Comet (Small Size) about 70º above horizon in N.W. from north to south." Although cloud cover was minimal during the late summer of 1862, Heger did not make any further notations of the comet until the September 1 entry, which reads "Comet obscured by Moon & cloudy weather."

No further celestial observations were noted at Vancouver Barracks after Heger's last entry in September 1862, and by 1870 the duty of recording meteorological conditions for the U.S. Army was transferred to the Signal Corps. The Army Surgeon General did continue to receive weather reports from post surgeons at approximately fifty Army posts by the 1890s, including Vancouver Barracks, but by that time the form used to record the data had changed so that only temperature and precipitation observations were made.