Part of a series of articles titled Selections from Historic Contact: Early Relations Between Indian People and Colonists in Northeastern North America, 1524-1783.

Article

Understanding Northeastern Contact Part V

https://www.loc.gov/item/2017855503/

Selections from the National Historic Landmark Theme Study

By: Robert S. Grumet, National Park Service, 1992

Understanding Northeastern Contact Part V

No matter how deeds worked, few colonists found Indians eager to sign papers surrendering their birthrights. Although most Indian people probably did not completely appreciate the full consequences of the first sales, they soon established creative misunderstandings with colonists interested in acquiring their lands. Even after establishing this relationship, most Indian people initially refused to sell all but the smallest portions of ancestral domains. Even fewer were willing to move among strangers after running out of land to sell. All Indians, however, were forced to face the fact that they ultimately could not stop settlers from trying to take their territory. Unwilling to capitulate outright to European demands, most gradually accepted the political realities of their situation by doing their best to slow the rate of land loss. Records of thousands of Indian deeds in archival repositories throughout the Northeast show that many succeeded in buying time by selling as little land as possible while extracting the maximum number of concessions from purchasers.

In the end, even this stratagem failed. By the time the newly independent colonies took their place among the world’s nations in 1783, newcomers had used deeds to extend sovereignty over most Indian lands within modern state boundaries east of the Appalachians. Like other dispossessed people, Indians forced to part with their lands had to remain on small reservations or missions, establish homes on land owned by other people, settle on vacant or unwanted territory, or move elsewhere.

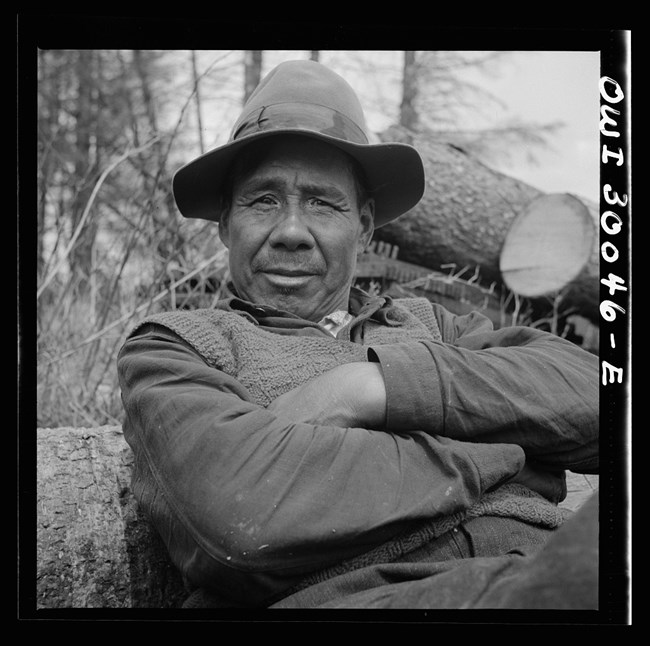

Once the land was obtained, speculators, powerful proprietary lords, and government administrators competed for the labor of settlers, servants, and slaves to make it productive. New landowners from Maine to Virginia used African-American, Indian, and European slaves, indentured servants, and hired laborers to clear brush from former Indian fields, cut down forests, and plant crops. Laborers also worked to dig mines, build mills, and erect townsites. New roads and old waterways were used to link newly emerging colonial communities throughout the region. Many aspects of these and other economic developments have been extensively examined. Not surprisingly, much of this documentation has focused upon colonists and their activities.

Last updated: June 3, 2019