Part of a series of articles titled Selections from Historic Contact: Early Relations Between Indian People and Colonists in Northeastern North America, 1524-1783.

Article

Understanding Northeastern Contact Part IV

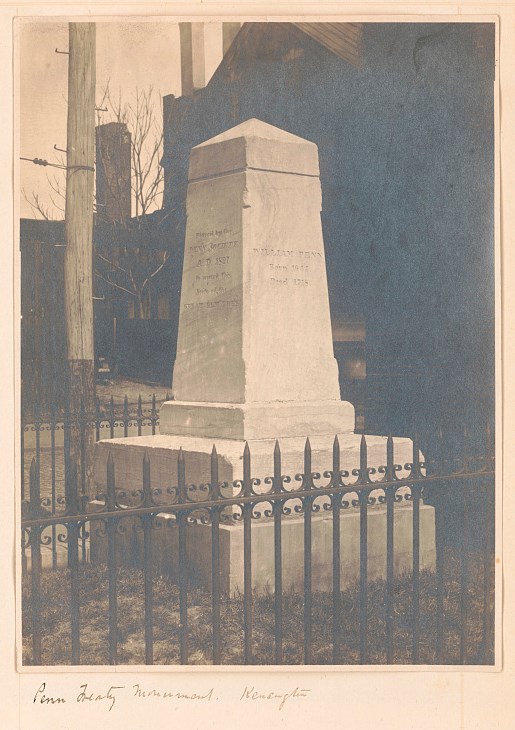

Collections of the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016647940/

Selections from the National Historic Landmark Theme Study

By: Robert S. Grumet, National Park Service, 1992

Understanding Northeastern Contact Part IV

Wherever they moved, newcomers struggled with Indians and each other for land and what it provided. Indian communities such as the Mohawk and other Iroquois nations anxious to maintain secure borders and adequate sources of supplies created buffer-zones around their heartlands by driving away or incorporating neighboring tribes. No less concerned with political and economic security, provincial authorities tried to obtain all the territory they could acquire. Many colonists used force against Indians and each other to seize land. Contending colonial administrators bickered over provincial boundaries and spheres of influence while their mother countries fought one another for control of the continent. Indian people ultimately were unable to avoid being embroiled in the wars growing out of these disputes. Some of these wars ended in devastating victories opening vast tracts of Indian land to colonial settlement. Others, however, resulted in far less decisive outcomes.

More thoughtful leaders warily weighed costs of war against potential benefits. Then as now, wars were disruptive and expensive. Their outcomes were neither always certain nor conclusive. Only a few struggles, like the above mentioned Pequot and Powhatan defeats, ended in clear-cut conquests. Most others dragged on interminably. French and English colonists battled one another off and on for more than 100 years while embittered tribesfolk like the Abenaki and Shawnee waged implacable war against invading settlers. More like feuds than wars, these imperial colonial struggles did not end until Americans began to impose centralized authority over most of the region after the War of Independence ended in 1783.

People concerned by the costs and uncertainties of armed struggle looked for less disruptive ways to expand their borders and defend what they already had. Most ultimately turned to diplomacy to come to terms with one another. Negotiations between Indians and colonists often were complicated affairs. Negotiators used highly stylized diplomatic forms blending European traditions and Indian protocols to reach agreements. Skilled forest diplomats, such as already mentioned Iroquois leader Teganissorens and New York’s Sir William Johnson, held treaties, negotiated covenant agreements, and affixed their names or marks to deeds. Concordances reached at these meetings established or maintained more or less stable relationships by settling disputes, formally transferring land rights, and by defining borders, rights, and obligations of treaty signatories.

Colonists began to use deeds to legitimate acquisition of Indian lands as early as the 1620s. Although Indian people did not believe in personal landownership, all recognized corporate land and resource rights. Such rights generally were transferred peaceably in ritualized negotiations or forcibly seized in no less ritually organized military conflicts. Unlike Indians, who did not possess writing before contact with Europeans, colonists employed written deeds to transfer land titles. Colonial authorities used deeds as a vehicle to extend sovereignty as well as ownership. Like earlier unwritten agreements, deed negotiations between natives and newcomers were ritualized transactions. More than a few guaranteed continued Indian rights to lands and resources within purchased tracts. When used in this way, Indian deeds served as a form of treaty as well as a type of title transfer.

Last updated: May 21, 2019