Last updated: March 4, 2020

Article

U.S. Takes Possession of Louisiana

This multi-part switcheroo, which many call “Three Flags Day,” was the culmination of a nearly year-long bureaucratic transfer between France and the U.S. -- we know it as the Louisiana Purchase.

Technically, the purchase was finalized on April 30, 1803. But things like this take time to implement, so the official ceremony of transfer finally took place in New Orleans in December 1803. Because winter was about to set in, residents north of New Orleans didn’t get word of the changes until much later. In March 1804 it was decided another official ceremony should take place in St. Louis.

But there was one little issue – St. Louis and the surrounding area was one the Spanish hadn’t gotten around to turning over to the French, in accordance with the Third Treaty of San Idelfonso of 1800. Officials thought it best to symbolize these changes by having a two-part ceremony – the land needed to first be transferred from Spain to France, then from France to the U.S.

How did this process actual work? On March 8, 1804, Spanish governor Carlos de Hault de Lassus posted a notice on the door of the city church notifying the public about the upcoming changes.

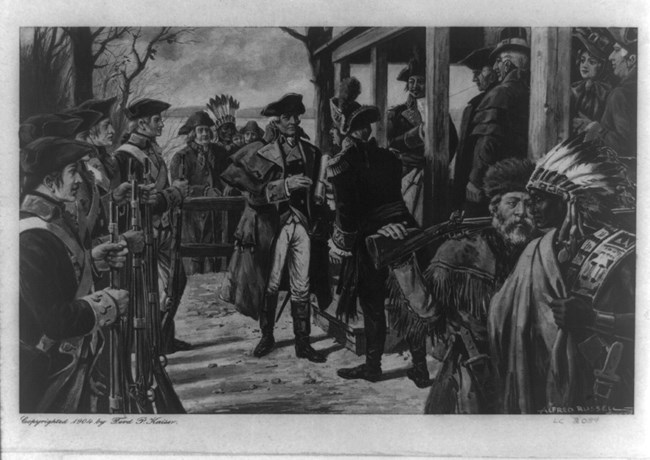

The next day, March 9, U.S. Army commander Amos Stoddard and Meriwether Lewis arrived from across the Mississippi River and marched to the governor’s mansion followed by a group of soldiers.

With a small crowd gathered outside, Stoddard and de Lassus signed some paperwork and de Lassus spoke, “The flag which has protected you during nearly 36 years will no longer be seen. From the bottom of my heart I wish you all prosperity.”

The flag of Spain was lowered and the flag of France took its place. A cannon boomed a salute. According to Walter Barlow Stevens in “St. Louis, The Fourth City,” the city’s citizens were excited to once again be French and rushed up to celebrate around the flag pole. For this reason the American officials agreed to leave the French colors flying until noon the next day. Stevens adds, “there was little sleep in old St. Louis during the hours the tricolor flew.”

Before 12 noon on March 10, everyone assembled again at the governor’s mansion, and since the French didn’t see the need to send an official representative, Captain Stoddard assumed the role for both France and the U.S. After he signed the papers and addressed the crowd, the French flag was dropped and the American flag went up. Stevens wrote, “Someone called for three cheers, but after all the celebrating the night before, people were exhausted and the response was not hearty.”