Last updated: July 28, 2023

Article

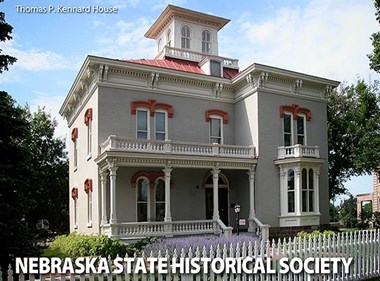

Thomas P. Kennard House: Building a Prairie Capital (Teaching with Historic Places)

“No man in his senses believes that the present location [is] to be permanent. It is in one corner of the state -- away from all lines of travel, possessing neither the advantages of railroads, navigable rivers nor telegraphs.”

Omaha Weekly Republican, Wednesday, August 7, 1867

This is how one of the state's leading newspapers described the site chosen to be the capital for the new state of Nebraska. The three commissioners followed the Nebraska Legislature's orders to relocate the capital, which went against the interests of the city of Omaha. The commissioners selected the tiny village of Lancaster as the future seat of government and changed the town's name to Lincoln in honor of the late president. These commissioners were Governor David Butler, Auditor John Gillespie, and Secretary of State Thomas Kennard.

The commissioners had high hopes for a grand capital city in the midst of open prairie near Salt Creek. In addition to the construction of a new capitol building, they planned for a state prison, mental asylum, and university, none of which existed in the newly-organized state. To bolster confidence, the men all risked their own money and built imposing homes, exhibiting some of the finest architecture in the state at the time. The Thomas P. Kennard House is the only one of these houses that still remains. Today, visitors can tour the house as a way to gain a deeper understanding of Lincoln's early years and an appreciation for those whose vision shaped its development.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places nomination form for the "Thomas P. Kennard House" (with photos), as well as primary and secondary resources in the collections of the Nebraska State Historical Society. The Nebraska State Historic Preservation Office, a division of the Nebraska State Historical Society, initiated this project and funded the initial research and writing of this lesson under a grant from the National Park Service. Research for this lesson was done by Lincoln Public Schools teachers David Beatty, Jill Carey, Sandra Dorn, Jennifer Fisher, Laura Parks, and Shawn Podraza; Annette Parde of Nebraska Wesleyan University; and staff at the Nebraska State Historical Society. Teaching with Historic Places staff edited the final draft. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be utilized in United State history courses, specifically in units on westward expansion, state government, and town building history.

Time period: Late 19th century

United States History Stndards for Grades 5-12

Thomas P. Kennard House: Building a Prairie Capital relates to the following

National History Standards:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Standard 2E – The student understands the settlement of the West.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Thomas P. Kennard House: Building a Prairie Capital

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity, & Change

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places, & Environments

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors, in local regional, national, and global settings.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, & Governance

Standard B - Describe the purpose of government and how its powers are acquired, used, and justified.

Objectives for students

1) To describe the challenges Nebraskans faced in selecting a state capital and how they responded to those challenges.

2) To explain how Nebraska's first commissioners worked to ensure the success of the capital city.

3) To identify factors important in planning a capital city and to design a state capital.

4) To create an exhibit about the history and significance of their community’s oldest buildings.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can be used directly on the computer or printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a small version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps showing the eastern counties of Nebraska and the plat for Lincoln;

2) three readings about the selection of Lincoln as the first state capital and the work of the state commissioners to ensure its success;

3) five photos of the city of Lincoln in the 1860s and 1870s and of the Kennard House.

Visiting the site

The Nebraska Statehood Memorial, Thomas P. Kennard House, is a historic site operated by the Nebraska State Historical Society. The Kennard House is located in Lincoln, Nebraska at 1627 "H" Street. For more information or to arrange a tour of the house, contact staff at the Nebraska State Historical Society.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Why do you think someone would build a house like this in a new city?

Setting the Stage

Westward expansion helped define the American experience in the 19th century. The United States extended from coast-to-coast, with the largest acquisition being the Louisiana Purchase (1803). New transportation technology, such as canals and railroads, and settlement acts like the 1862 Homestead Act helped spur settlement. Thousands of people left the eastern half of the continent looking for better opportunities in the west. Sitting in the middle of all of this movement was Nebraska and thousands of people settled there to form agricultural communities with the land they acquired from the government's land holdings.

With the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, Congress created the Kansas and Nebraska territories out of land acquired under the Louisiana Purchase. This bill overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had banned slavery in new territories in the north. The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed the people of each new territory to decide whether they would allow slavery or not. After experiencing bloody disputes over slavery, Kansas became a free state in 1861. The initial boundaries of the Nebraska Territory encompassed much more land than today's borders. But by 1864, parcels of land had been taken away, leaving the borders of Nebraska similar to that of today. By that time, it was clear that Nebraska had firmly entered the road to statehood.

The United States Congress gave Nebraskans the authority to draft a state constitution in 1864, but none was drafted. In 1866, two years after the enabling legislation, a constitution drafted by the legislature was narrowly ratified and sent to the President and Congress for approval. Because Congress required the Nebraska state constitution be changed to allow black men the right to vote, President Andrew Johnson vetoed the statehood bill. He believed that Congress had no right to dictate to states provisions of their constitutions. Congress overrode the veto and Nebraska entered the Union as the 37th state on March 1, 1867.

Locating the Site

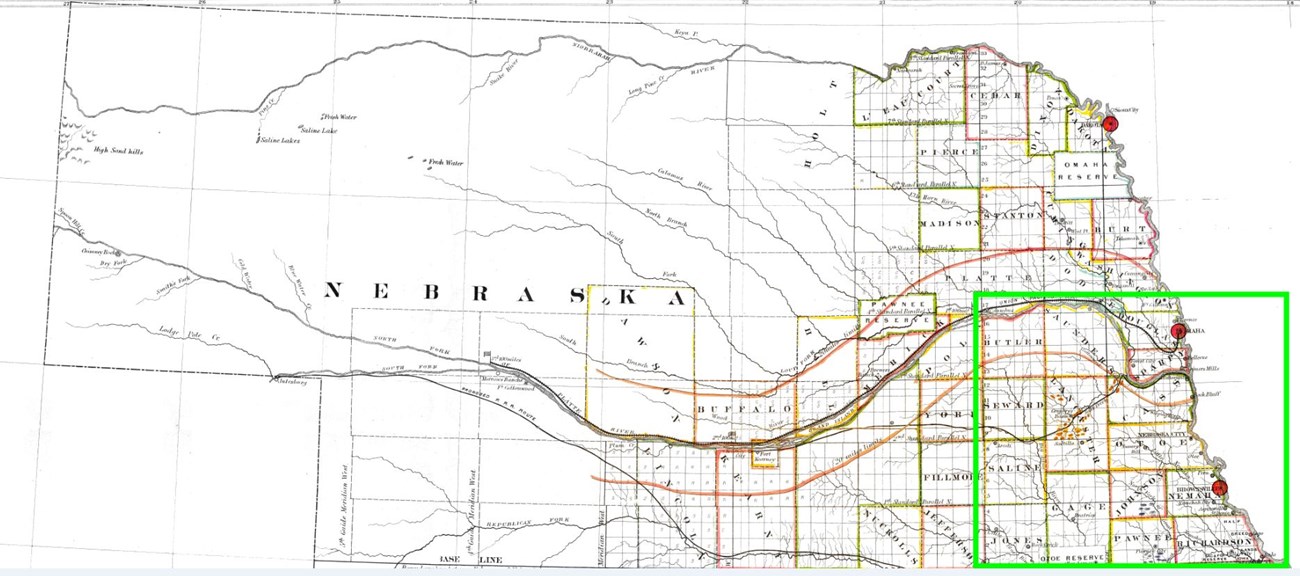

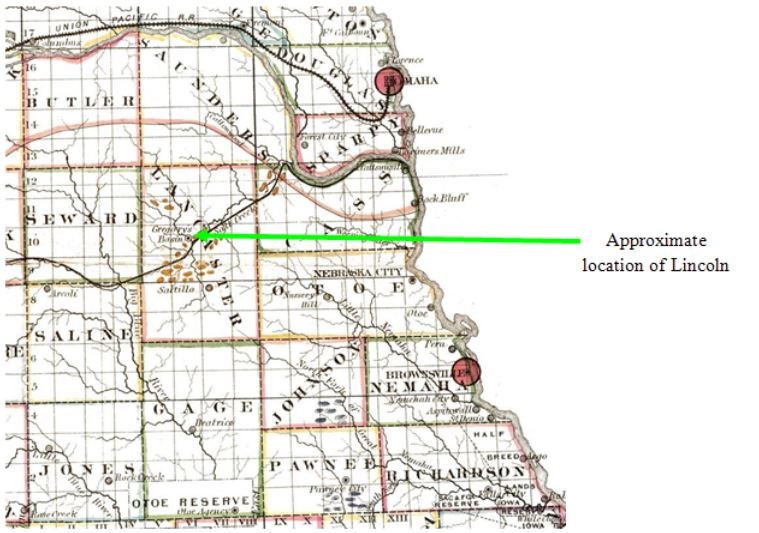

Map 1: 1866 U.S. General Land Office Map of Kansas and Nebraska Close Up of Southeast Nebraska

The lower map is a close-up of southeast Nebraska in 1866, before Nebraska became a state.

The towns of Omaha, Plattsmouth, Nebraska City, and Brownville were founded shortly after the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which opened Nebraska Territory to settlement. These towns were founded on the Missouri River, the eastern boundary of Nebraska Territory, and took advantage of the Missouri River for commerce. Omaha was the territorial capital. Soon, settlement moved west. A new location for the capital was proposed when Nebraska became a state in 1867. The new location would have to possess economic potential and a more central location.

Questions for Map 1

1) Locate the city of Omaha, the Platte River, and the site for the future city of Lincoln on this map. Also locate Saunders, Butler, Seward, and Lancaster counties. The state legislature instructed the capital commissioners to choose a site for the new capital city from these counties. Why do you think those specific counties were chosen?

2) The new capital of Lincoln was established just east of "Gregory's Basin" in Lancaster County. Compare how far that area is from the well-established Nebraska cities of the day: Omaha, Plattsmouth, Nebraska City, and Brownville. Do you think this area was a good place for the new capital? Is this where you would have located the capital? Why or why not?

Locating the Site

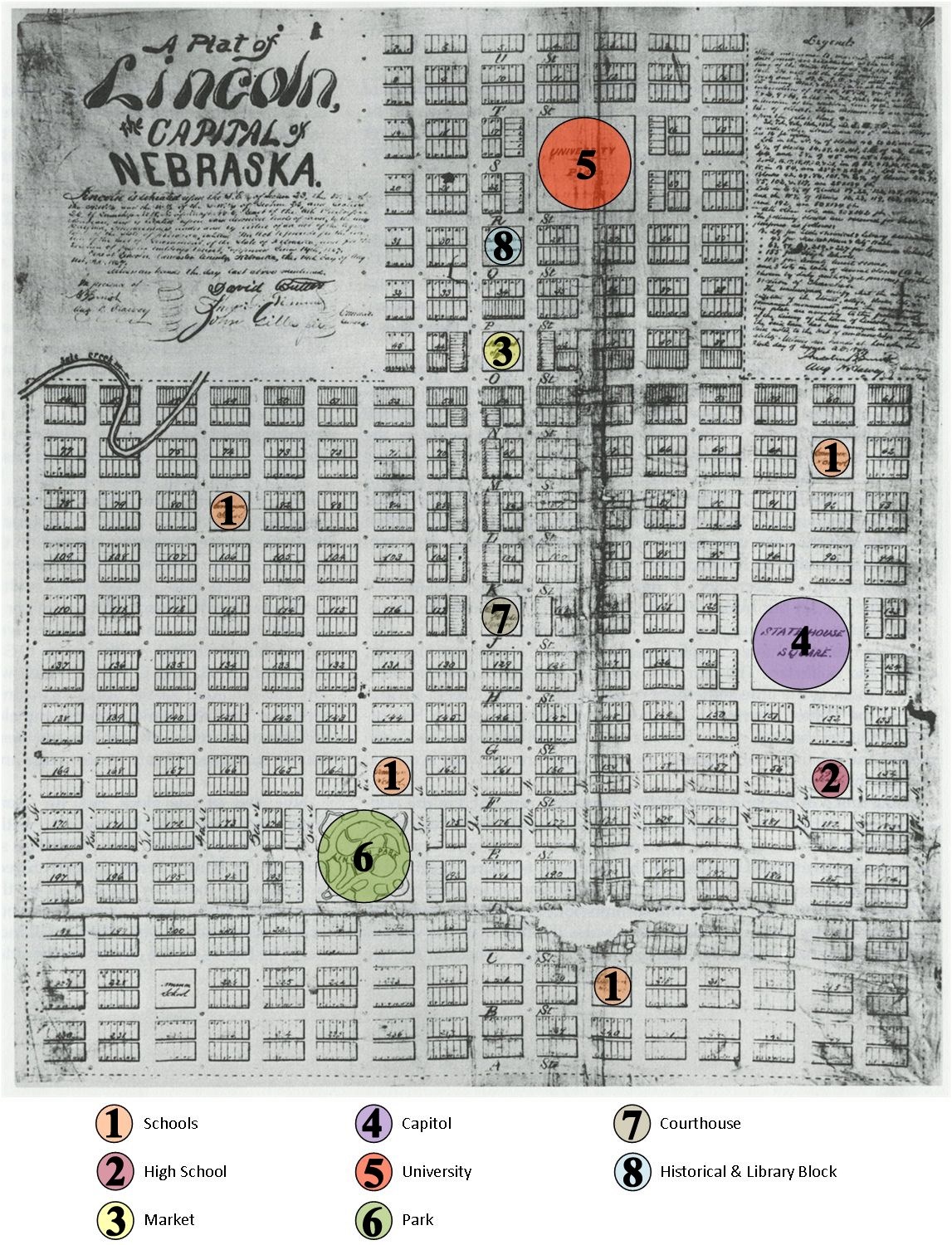

Map 2: The Original Plat of Lincoln, 1867

(Nebraska State Historical Society)

This is the plat for the new capital city of Lincoln, drawn before any new buildings were constructed. A "plat" is a map of a town, used for legal titles. Properties are identified in this map by blocks. Within each block are individual lots, meant as the location for buildings. To promote the new city, the plat identified areas reserved for certain public uses and institutions. The plat made provisions for a courthouse, public market, parks, a state university, a state historical association and library, and schools. Although not denoted on the map, lots were offered to religious institutions for churches.

The large "State House Square" was the designated location for the new capitol building. Nebraska Secretary of State Thomas P. Kennard and Auditor John Gillespie bought lots for their private homes. The lots were in close proximity to the new capitol building.

Questions for Map 2

1) What institutions were included on the original plat? Why might the map have shown the location of places before any buildings were built? Why were certain blocks reserved for certain purposes? How might that be useful in planning and promoting the city? Would you want to move to a city like the one in the plat?

2) If you were planning a city, what buildings, institutions, and other places would you be sure to include on the map? Why would you include them?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Lincoln's Beginnings

In 1866, the Nebraska Territory was eager to become a state. The people had adopted a state constitution and elected state government officials. These new officials included the Governor, Secretary of State, State Auditor, State Treasurer, and Chief Justice. On March 1, 1867, President Andrew Johnson signed the bill making Nebraska the 37th state. Choosing the location for a new state capital was one of the first issues facing the new government.

The territorial capital had been in Omaha since 1854. It stayed there despite protests from angry residents south of the Platte River. They argued that they were not fairly represented in the legislature. The new state government created the Capital Commission in 1867 to select a new location. Its members were Governor David Butler, Secretary of State Thomas Kennard, and Auditor John Gillespie. Together the Commissioners chose the small village of Lancaster, which they chose in part because of its proximity to salt deposits. At that time, Lancaster consisted of two stores, one shoe shop, six to seven houses, and about thirty residents.

The Commission submitted their plan to the state legislature. They faced no major opposition. Omaha Senator J. Patrick attempted to provoke some, but failed. He tried to revive Civil War bitterness by replacing the name "Capital City" in the bill with "Lincoln" (for Abraham Lincoln). The bill passed anyway. "Lancaster" became "Lincoln," Nebraska's new state capital.

Newspapers in Omaha fiercely criticized the decision to move the capital. They objected for several reasons. First, they pointed out that the territorial capitol building was still in good condition. Therefore, continuing to use it would save money. Secondly, they argued that the town of Columbus was a much more central location if the capital had to be moved. Finally, Lincoln was not accessible by a navigable river and it did not yet have railroads, permanent roads, telegraphs, or much commerce to support a growing city. Lincoln's supporters cited the area's naturally occurring salt deposits as a source of potential wealth. The salt industry did not expand as many hoped, but the Capital Commission moved forward with great faith in Lincoln.

The plan was to pay for the construction of the new capitol building by selling lots in the new city. The first sale did not go well. Lots sold for much lower prices than their appraised values (an estimation of monetary worth). At their going rate, they would not raise enough funds to build the capitol and their attempts to move the state capital to Lincoln would be considered a failure. At this point the Commissioners, with a group of Nebraska City businessmen led by James Sweet, took action. They agreed to bid lots up to at least their appraised value to encourage other buyers. This group risked personal fortunes. If the plan failed, then their money was lost. However, the plan succeeded and Lincoln began to grow rapidly. By October 9, 1869, the Nebraska State Journal reported that 110 homes and businesses had been built in Lincoln. They averaged four buildings a week! That was quite a change from just 10 buildings in July 1867.

The three commissioners next turned their attention to their own houses. Thomas Kennard built a splendid residence on his lot. Both the stylishness and size reflected Kennard's high social status. Not only was the house designed in good taste for the time, but it also included two parlors and a servants' wing. David Butler and John Gillespie also built impressive homes. The Lincoln newspaper, the Nebraska Statesman, stated that the three houses cost between $8,000 and $15,000 (which would be about $940,000 to $1,760,000 today). The paper gushed by saying that the homes "exceed in tastefulness of design any private dwellings in the State." With these homes, the Commissioners demonstrated that, even in their private lives, they believed in the future of the new city. This display of faith was an important factor in the struggling city's ultimate success.

Questions for Reading 1

1) Which state officials were elected in Nebraska's first state election?

2) How many buildings were in Lancaster in 1867? How many buildings were there in Lincoln two years later?

3) What type of house did Kennard build? Why did Kennard build such an elaborate house? How did it show confidence in Lincoln?

4) What might have motivated somebody to want to move the state capital from already-established Omaha to the small town of Lancaster?

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Newspaper Article, from the Early Years of Statehood

The following is an opinion article published by the Nebraska Statesman newspaper in 1869. In it, the author responds to an earlier article published by the Nebraska City News.

The Nebraska Statesman

July 10, 1869

Lincoln, Nebraska

The [Nebraska City] News (we think) asks "who of the state officers has made the most money out of Lincoln?" We do not keep the private books of [our?] State officers, but believe we are safe in saying that Governor Butler has. He is probably $25,000 better off than when Lincoln was located. Mr. Kennard has made several thousand dollars, Mr. Gillespie has some; so has Mr. Sweet. We (not a State officer, however), have made eighty-one cents clear. Whose business is it? Yet, although it is nobody's business, we propose to state a fact or two.

On the day of the first sale, September 17, 1867, Lincoln was but a hair's breadth from a fizzle. The weather was cold and drizzly, not a tenth part of the buyers who had promised to be here had, in consequence of the weather, been able to arrive. Bidders, speculators, State officers, and small boys, felt dispirited and disheartened, and when the first lot was put up the auctioneer's hammer fell with a dull thud like a clod on a coffin. The thing looked busted. The Commissioners looked busted--for they were in for $1,000, which they had borrowed on their personal credit to pay the preliminary expenses. Everybody looked busted, and the forlorn appearance of affairs was not dispelled until Butler, Kennard, Gillespie, and Sweet, by bidding freely for lots at considerable advances over appraisements, and showing strangers that they were willing to take the risk, induced others to bid and buy, and thus established the first success. The Commissioners and Mr. Sweet bought, in all, at the first sales, about $20,000 worth of lots. The Governor and Mr. Sweet being tolerably well off planked down the cash. The other two not being blessed with large fortunes, sold part of their possessions, borrowed some money from their friends, and scratched gravel for the balance, and paid for their lots. They have also purchased freely at subsequent sales. They bid against determined opposition and had to pay as good prices as anybody.

Lots which were appraised like others on the same street, at $50, and the Governor bought at $80, have been sold as high as $1,200. Others bought by other State officers have brought one, two, and as high as six hundred per cent. Real estate business has been profitable in Lincoln.

Whose business is it, if the State officers have each made ten cents or ten thousand dollars? They deserve all they have made. They took big risks—risked all they had, and fortune—by their faithfulness in carrying out the "Lincoln scheme" has favored them. It was their own money they bought with, and it was their own property they have sold for more money than it cost. These men have had a burden to carry, and they have carried it well. They have never, at any moment, shrunk from any of their responsibilities; and at all times stood ready to perform any extraordinary service that the exigencies of the case required. When the work on the State House exceeded the amount of money received at the first sale, the Commission were waiting for the second sale to provide the necessary funds—and in the face of the most dismal cloakings and predictions that after all Lincoln would still fail—these men did not hesitate to advance the money from $5,000 to $10,000 to shut the clamorings of unpaid workmen. Out of their own pockets and credit, the risked the necessary funds. They knew that if Lincoln succeeded they would recover their loans; and if it failed, that Lincoln Sale wouldn't them, financially, politically or otherwise.

But the experiment – which the founding of this town was – is a success, and for the success thereof the credit is due to David Butler, Thomas P. Kennard, John Gillespie, and James Sweet. They saved it when fizzling and their cash account has been increased thereby—in an honest, legitimate way, by buying and selling lots. Now, whose business is it?

Questions for Reading 2

1) Why did the Nebraska Statesman, printed in Lincoln, call the founding of Lincoln an "experiment?"

2) According to the editorial, how did the Commissioners and James Sweet show and establish confidence in Lincoln?

3) What did Thomas Kennard and John Gillespie risk in this "experiment?" What would they lose if it failed?

4) Why do you think this article was written? Did the Nebraska Statesman defend or attack the commissioners? What criticisms do you think the Nebraska City News had made of the Commissioners' action? Do you think it was fair that they profited from the sale of the lots?

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Architecture of the Kennard House

Thomas Kennard built his house in 1869 at a cost of about $14,000 ($1.64 million in early 21st century dollars.) Today it is the oldest existing house in the original plat of Lincoln. Architect John Keyes Winchell of Chicago designed it, and he prepared drawings and detailed written instructions for the builders. The house originally included a rear wing with a kitchen, dining room, and servants' quarters. Later owners removed that part of the house in 1923.

The architect and builders chose both local construction materials and materials from other areas of the country for the house. If you visit the Kennard House, you can still see the stones that make up the foundation. Made of sandstone, they were quarried from the banks of Antelope Creek, near the present location of the Lincoln Children's Zoo. Local clay was used in manufacturing the brick for the walls, but a mill working company outside of the state made the woodwork in the house. This company shipped the woodwork to Lincoln by wagon, as the railroad had not yet reached the new capital. A new manmade material called "Frear Stone" formed the arches above the windows which were shipped to Lincoln from the factory.

The Kennard House is an excellent example of the style of architecture called "Italianate." The word "Italianate" refers to types of early buildings found in Italy. This style was fashionable in the United States from about 1840-1885. The Kennard House displays the following characteristics of the Italianate style:

-

Low sloping roofs

-

Overhanging eaves (the edges of the roof) supported by pairs of decorative brackets

-

Narrow windows with arches

-

Porches with railings on the roof

-

Cupola (a short tower on the roof)

Questions for Reading 3

1) In what architectural style did Thomas Kennard build his house? Where did the inspiration for that style come from? What are the main characteristics of the style? Why do you think Kennard might have chosen this style?

2) Do you think that Kennard's house was a typical house in Lincoln at that time? Why or why not? Why do you think Kennard wanted to build a house like this in Lincoln? (Refer back to Reading 1, if necessary)

3) Where did the materials used to build Kennard's house come from? What might have determined whether builders could use local materials or not?

Visual Evidence

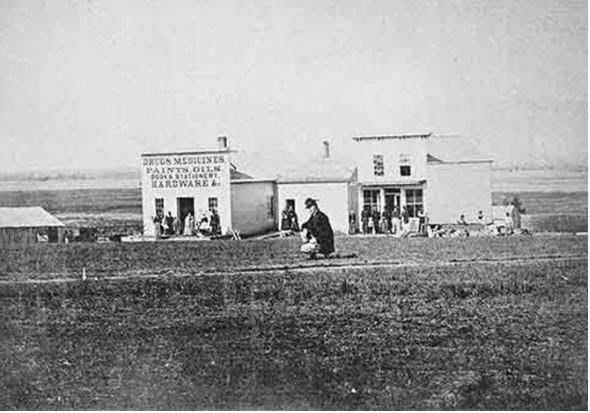

Photo 1: Thomas Kennard and John Gillespie houses, 1872

Questions for Photo 1

1) Based on the architectural description in Reading 3, which building in Photo 1 is the Kennard House? Which is the Gillespie House?

2) Compare and contrast the Kennard House with the house in the lower foreground of Photo 1. How do you think the lifestyles of the residents in these two houses would have differed?

3) Think about Lincoln's purpose. If you were Thomas Kennard, where in the community would you have wanted to build your house? From where do you think Photo 1 might have been taken? (Refer back to Map 1 and Reading 1, if necessary.)

Photo 3: Portion of the 1872 Panoramic of Lincoln, taken from the Capitol, looking northwest

Photo 4: Portion of the1872 Panoramic of Lincoln, taken from the Capitol, looking north

The numbers in photos 3 and 4 are for the following features: #11 is K Street, #12 is 14th Street, and #13 is University Hall at the new state university. The fence shown in Photo 3 surrounds the Capitol.

The photos from 1872 are part of a panoramic photo that also includes the view of the Kennard House used previously in this lesson (Photo1). You can use Photo 1 to help with the following questions.

Questions for Photos 2-4:

1) Look at Photo 2. What kind of business is shown? What other types of business do you think would be necessary for a new town?

2) What do you notice about the houses and buildings in 1872? Are most simple or extravagant? How many stories do most have? What materials were used in their construction?

3) Is there a pattern to the roads in Photos 3 and 4? What do you think the road surface probably was at the time? Compare what you see in Photos 3 and 4 with Map 2. Do you think the Commissioners' vision for Lincoln was beginning to be realized? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Kennard House, 2010

Questions for Photo 5

1) What features of Italianate architecture do you see on the Kennard House in Photo 5? (Refer to Reading 3, if necessary.)

2) The historic Kennard House today is also the "Nebraska Statehood Memorial." Why do you think Nebraskans chose this house to be a "statehood memorial"?

Putting It All Together

By studying the Thomas P. Kennard House: Building a Prairie Capital lesson, students have learned how and why Nebraska established its capital city at Lincoln when it gained statehood. This lesson introduced ideas about what types of buildings people want in their capitals and the challenges civil leaders face when they plan a new state or city. Use the following activities to broaden and test students' understanding of these subjects

Activity 1: Breaking news in the territory.

Like Nebraska, many of the United States' western states were once territories founded in the 19th century. Assign each student or a group of students a state (including Nebraska) with an official territorial history. Then, ask them to imagine they are newspaper reporters living in the territorial seat and writing for the territory's residents. Have them research their state's history and then write a descriptive newspaper article about the creation of the state as if it just happened. There are many resources online that describe how to write a news article, including one from Purdue University.

Information in the articles should reflect the students' understanding of the history of the United States' involvement in the region, the economic makeup of the territories just before statehood, the groups or individuals who pushed for the territory to become a state and why, major federal laws or acts that influenced the territory and the creation of the state, major national or international events that influenced the creation of the state. The newspaper article can include quotes with attribution and students should also submit one historic image related to statehood when they turn in their articles.

Organize the articles and images in a word processor or graphic design program to create mock newspaper pages that you can display in the classroom. Ask each student or student group to present a short oral report to the class summarizing how the state became a territory and eventually a state. Were there any obstacles that had to be overcome or any controversial local, regional, or national political issues? Then, hold a class discussion comparing and contrasting the various stories and issues.

Activity 2: City Planning: Design a state capital.

Visit your local library or historical society or search online for a 19th century or early 20th century map or plat of your state's own capital. Some cities had "bird's eye" views created, which show natural features, early buildings, and streets. These were drawn by artists as if from the air or as a bird flies.

Have students study the map and identify important structures. These might include businesses, government offices, schools, libraries, cemeteries, parks, houses, and transportation systems (roads and railroads). After they've had time to look at it, ask them the following questions:

-

Why were these structures located where they were?

-

Why were they important to this city?

Now divide the class up into small groups. Each group should pretend that they are commissioners designing a state capital. Have each group create a map of their city, and select natural and manmade features for it. Students should first start with where the town is to be located. Ask them to consider the following when designing their capital city:

-

What topography (natural features, such as hills, streams, rivers) was selected as being the most favorable for the location of the new town? How did it influence the location?

-

Were there existing railroads or highways that influenced the location? Canals or sea ports?

-

What kind of economy does your city have (industry or agriculture)? How does this affect the ways people live and work in your city? How does this influence the way the city looks and the types of buildings it has?

-

What other factors in your state's history, population, and culture influenced the town's location?

After these exercises, have each group present their town to the class and give a persuasive speech that explains why their town would make a good state capital.

Activity 3: Local history on the Web

Ask your students to research their town's early history and turn their discoveries into a collaborative online resource that can take shape as a blog or website (various online resources will allow you to do these for free). Internet research might not provide enough local history information for this assignment, so take the students on a field trip to or ask them to visit independently their local library, historical society, or county courthouse to research the history of their county and county seat. Locate an early plat map of the city.

Break the class up into small groups and divide the following questions among the groups:

-

Who first settled in your county or town? What kinds of uses did they find for the land?

-

Who founded your county or town? How many people settled there at the time it was founded? Did many of them come from the same place?

-

How did the region's industry/agriculture/society/culture change around the time of the founding? If it didn't change then, what was it like at that time?

-

What was the origin of the county's name? Why was that name chosen? What meaning did it have to the people who founded the county and the people who lived there?

-

Who named your town and what was the origin of that name? What meaning did it have to the people who founded the town and the people who lived there?

-

What historic events and movements were happening at state and national levels at the time your county or town was founded? How did they effect the founding of your county or town?

-

When was the county seat selected? Did the town exist before it became the county seat? Who chose it and why did they choose it? Was there controversy over the selection of the county seat?

-

What buildings were constructed at the time your town was founded? Do any still exist? Are they listed on the National Register of Historic Places? What kind of architecture or history do they represent?

Groups should also find digital images related to the questions they researched. With permission from the copyright holder, they can use historic artwork or photos that show the county or its people at the time of its founding. They can also look for government symbols like a seal or flag (these are in the public domain) for the web resource.

Each group should write a paragraph answering the questions they were assigned. You or the students should decide what kind of resource will best display their findings. A blog could showcase each group's findings in their own post. A website might organize the paragraphs by topic and have three or four pages. Contact the local historical society, library, or other groups with knowledge or expertise in local history Also, find out if they can link to your class's project from their own website.

Activity 4: Places where your state made history.

Have students investigate the historic buildings in your community and determine the oldest ones. Students can consult the National Register of Historic Places database and their state historic preservation office's website to find historic places. Also, your local historical society or library can assist you.

Divide the class into small groups and assign each group a different building to study.

-

Visit your local historical society or library and research secondary and primary documents to learn about the building.

-

When was the building constructed and for what purpose?

-

Who built the building?

-

Are there early photographs of the building?

-

Are there old maps of the town that show the building?

-

-

Visit the building.

-

What style of architecture is it?

-

What materials were used in its construction?

-

Is it used for the same purpose today as it was when it was built?

-

-

Take photographs of the exterior of the building to compare to early photographs.

-

How has it changed over the years?

-

Why do you think these changes were made?

-

Have students take their findings and create a poster series that the class can exhibit in your school. Consider offering the posters to their local library, historical society, or government to use as a temporary exhibit.

If any of the buildings your students selected are not on the state inventory or National Register of Historic Places, consider having your class select one of the buildings, contact the State Historic Preservation Officer, and initiate the process preparing and submitting a draft nomination for that building.

Thomas P. Kennard House: Building a Prairie Capital

Supplementary Resources

In this lesson, students learned about the Kennard House and the role it played in founding Lincoln, Nebraska, in the 19th century. Those interested in learning more will find much useful information on the internet. Some sources are:

Thomas P. Kennard House, Statehood Memorial

This is the official webpage for the Kennard House. It includes photos of the house and of the capital commissioners. more detailed information about the house, and information about visiting the house.

Andreas’ History of the State of Nebraska (1882)

This is another online version of a printed book. It has the history of the capital removal as well as population figures for all counties in Nebraska over several years.

NebraskaStudies.org

This website offers teachers, students, and history buffs access to archival photos, documents, letters, video segments, maps, and more ─ capturing the life and history of Nebraska from pre-1500 to the present.

Historical Maps of Nebraska

Hall County, Nebraska has compiled a digital collection of early Nebraska maps. They were scanned from atlases published between 1850 and 1901. They also utilized collections at the Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer and the Nebraska State Historical Society. The maps pertain to all of Nebraska.

Panoramic Maps from the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress offers a collection of 19th and 20th century panoramic maps that show a "bird's eye" view of American towns and cities. The main page includes guidance for teachers using these maps in the classroom.

American Memory from the Library of Congress

This digital archive at the Library of Congress provides free access to more than nine million digitized items that document U.S. history and culture.

Tags

- nebraska

- nebraska history

- westward expansion

- kansas-nebraska act

- settlement of the west

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- migration and immigration

- mid 19th century

- gilded age

- art and education

- immigration and migration

- statehood

- westward migration

- twhplp