On July 17, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln authorized the use of African Americans in federal service by issuing the Second Confiscation and Militia Act. It was not until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, however, that black men could serve in combat.

"[L]et the black man [...] get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder [...], and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship[...]." Frederick Douglass

Library of Congress

The United States War Department issued General Order Number 143 on May 22, 1863. This order established the Bureau of Colored Troops and it recruited many African American men into the Union army. The regiments of the Union army that were composed of African American men were called the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.).

Soon there were 200,000 black soldiers serving in the Union army and navy. These men were paid less than white officers, were given old and worn uniforms and poor equipment, and could not become officers. Despite the unfair treatment, black men volunteered to take part in combat.

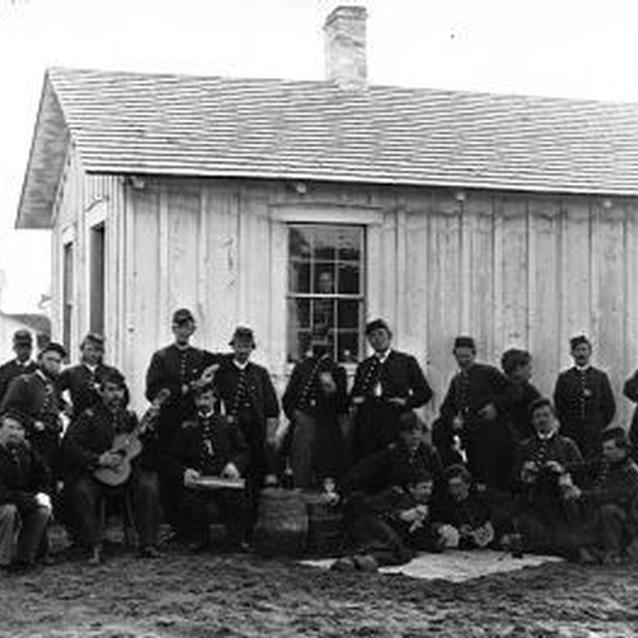

The U.S.C.T. suffered from racial discrimination despite serving the Union war effort. Seldom seeing active battle, many troops were assigned as laborers, construction workers, and guards on fortifications throughout the Union, including the Defenses of Washington. The 28th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops was one of the units attached to the Defenses of Washington. This regiment of infantry was established on November 30, 1863 by Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton. Reverend Willis Revels of the African American Episcopal Church was the chief recruiting officer. The recruits trained for three months and on April 25 1863, six companies of the 28th U.S.C.T. left Indianapolis for Washington, D.C. where they were attached to the capital's defenses.

Another regiment designated to the defenses was Company E, 4th U.S Colored Infantry, recorded by photographers at both Fort Lincoln and Fort Slocum.

Last updated: August 14, 2017