Last updated: March 30, 2023

Article

The United States Air Force Academy: Founding a Proud Tradition (Teaching with Historic Places)

The Air Force Academy is built upon a proud foundation and so it should be. For the Academy is a bridge to the future, gleaming with promise of peace in a stable, sane world….Our airpower has kept the peace…it is keeping the peace, God willing, it will keep on doing so. This Academy, we are founding today, will carry forward that great effort.

--Air Force Secretary Harold E. Talbott, July 11, 1955

Set in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains near Colorado Springs, Colorado, the Air Force Academy's sleek modern architecture, monumental scale, and dramatic setting combine to create a stunning national monument. Its gleaming aluminum, steel, and glass buildings are not only a reflection of modern architecture but are a "living embodiment of the modernity of flying."1

Established during the first decade of the Cold War, when the threat of nuclear attack and Communist expansion loomed large, the Air Force Academy symbolized the importance of air power to our nation's security. As the Air Force became the nation's primary military arm during the 1950s, the Air Force Academy was charged with training and educating officers capable of meeting the challenges of the nuclear age. Today, the Academy continues its proud tradition of providing the Air Force with a corps of dedicated officers.

1Testimony of Harold E. Talbott, Secretary of the Air Force, U.S., Congress, House of Representatives, Hearings before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, 84th Congress, 1st session, 1955, 224.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Historic Landmark nomination file, "United States Air Force Academy, Cadet Area" (with photographs), and other materials on the Air Force, the Air Force Academy, and the Cold War. This study was conducted in partnership with the United States Air Force Academy through a Cooperative Agreement with the Organization of American Historians. The lesson plan was written by Brenda K. Olio, former Teaching with Historic Places staff member. The lesson was edited by staff at the United States Air Force Academy and the Teaching with Historic Places program. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, and geography courses in units on 20th-century military history, aviation history, the Cold War, defense policies under Truman and Eisenhower, or modern architecture.

Time period: Early to mid 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

The United States Air Force Academy: Founding a Proud Tradition

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the causes of World War I and why the U.S. intervened.Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

-

Standard 3B- The student understands World War II and how the Allies prevailed.

-

Standard 3C- The student understands the effects of World War II at home.Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands the extent and impact of economic changes in the postwar period.

-

Standard 1C- The student understands how postwar science augmented the nation's economic strength, transformed daily life, and influenced the world economy.

-

Standard 2A- The student understands the international origins and domestic consequences of the Cold War

.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

The United States Airforce Academy: Founding a Proud Tradition relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard C - The student uses appropriate resources, data sources, and geographic tools such as aerial photographs, satellite images, geographic information systems (GIS), map projections, and cartography to generate, manipulate, and interprets information such as atlases, data bases, grid systems, charts, graphs, and maps.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people creates places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard G - The student identifies and interpretss examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard F - The student describes the role of institutions in furthering both continuity and change.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard G - The student describes and analyzes the role of technology in communications, transportation, information-processing, weapons development, and other areas as it contributes to or helps resolves issues.

-

Standard I - Standard I - The student gives examples and how governemnts attempt to acheive their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution and Consumption

-

Standard F - The student explains and illustrate how values and beliefs influence different economic decisions.

-

Standard I - The student uses economic concepts to help explain historical and current developments and issues in local, national, or global contexts

Theme VIII: Science, Technology and Society

-

Standard A - The student examines and describes the influence of culture on scientific and technological choices and advancement, such as in transportation, medicine, and warfare.

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationship to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants, and security.

-

Standard C - The student describes examples in which values, beliefs, and attitudes have been influenced by new scientific and technological knowledge, such as the invention of the printing press, conceptions of the universe, applications of atomic energy, and genetic discoveries.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard C - The student describes and analyze the effects of changing technologies on the global community.

-

Standard D - The student explore the causes, consequences, and possible solutions to persistent, contemporary, and emerging global issues, such as health, security, resource allocation, economic development, and environmental quality.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explain the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

Objectives for students

1) To describe how and why the role of military air power expanded from World War I to the Cold War.

2) To evaluate how the Cold War influenced national defense policies in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

3) To identify the major reasons why the United States Air Force Academy was established.

4) To describe the architectural style and layout of the Air Force Academy and analyze how it symbolizes both the time period and the mission of the Academy.

5) To research the impact of the Cold War in their own community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

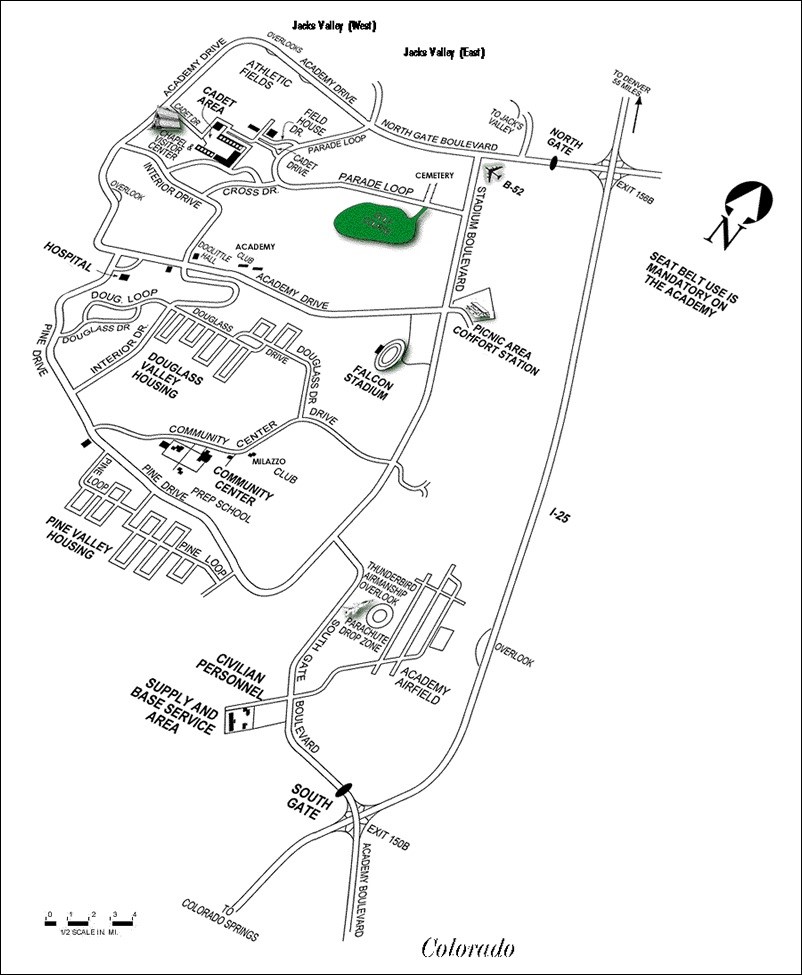

1) two maps showing Colorado Springs and the Air Force Academy;

2) three readings on the Air Force, the early Cold War era, and the establishment of the Air Force Academy;

3) one illustration of a 1954 Colorado Springs Committee brochure;

4) one drawing of the Air Force Academy site plan;

5) six photos of the Air Force Academy.

Visiting the site

The U.S. Air Force Academy is located eight miles north of Colorado Springs, Colorado. The campus is open to visitors daily between the hours of 5:30 a.m. and 6:00 p.m. A Visitors Center features informative exhibits on cadet life. Visitors must use the North Gate Entrance, exit 156B on Interstate 25. For more information, visit the Air Force Academy website.

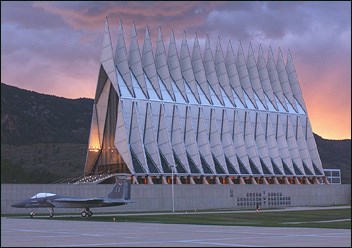

What purpose do you think this building was designed to serve?

Setting the Stage

The United States Air Force became an independent military service equal to the Army and Navy in 1947. It had existed as an air division of the Army since 1907, when the War Department created the Aeronautical Division to study the military potential of aircraft. In 1909, six years after the Wright brothers' flight at Kitty Hawk, the Army purchased its first airplane.

For several years the military believed that airplanes were best used as support for ground troops. Advances in airplane and weapons technology during World War I and World War II, however, proved that air power could play a major role in national defense. By 1947, the newly-established Air Force had to meet the challenges of the modern age, including the threat of nuclear attack by the Soviet Union. To do so, it would require well-trained and educated officers.

In 1954, the Federal Government authorized the creation of the United States Air Force Academy. It was to serve as the undergraduate educational institution of the Air Force in the same tradition as the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, and the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. These institutions, established in 1802 and 1850 respectively, had produced the nation's top military leaders for generations. The Air Force Academy quickly rose to the challenge and produced highly-trained officers qualified to lead the Air Force during the early Cold War, a time when the nation's defense policies relied heavily on air power.

The Air Force Academy is located eight miles north of Colorado Springs, Colorado, in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Pikes Peak rises more than 14,000 feet in the distance and the Rampart Range (6,000-7,000 feet) forms the Academy's western boundary. The Academy is one of the nation's highest (ranging between 6,380 and 8,040 feet) and largest (18,500 acres) campuses. Despite its elevation, the Colorado Springs area offers a moderate, sunny climate.

Before selecting the Colorado Springs site in 1954, the Air Force Site Selection Commission considered more than 550 proposals in 45 states. Some of the specific criteria the committee looked for included: an area not less than 15,000 acres; proximity of cities within 50-mile radius; no extreme heat or cold; and transportation accessibility.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate Colorado Springs and describe its location within the state of Colorado.

2. Locate the Air Force Academy. What natural features are nearby? How would you describe its setting?

3. Based on the criteria listed above, did the Colorado Springs site seem like an appropriate location for the Air Force Academy?

The Academy property runs seven miles north to south and roughly four miles wide. The academic complex, known as the Cadet Area, covers about a fifth of a square mile and includes cadet living quarters as well as academic and recreational buildings. The 18,500-acre site also contains housing and other facilities capable of supporting a population of several thousand. Nearly 100 miles of paved roads link the various areas of the Academy.

Questions for Map 2

1. Locate the Cadet Area. How large is it? What types of buildings does it include? Why might these buildings be grouped together?

2. What other buildings and facilities does the Academy include? Why do you think these are necessary?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: History of the United States Air Force

Orville and Wilbur Wright achieved the world's first controlled, powered flight on December 17, 1903, on North Carolina's Outer Banks. Soon thereafter, they began trying to convince the Federal Government of the airplanes' military potential. On August 1, 1907, the War Department created the Aeronautical Division within the Army's Signal Corps to study "ballooning, air machines and all kindred subjects." When the Army advertised for an air machine that could carry two people and fly at speeds of 40 miles per hour, the Wright Brothers produced a plane that exceeded these specifications. On August 2, 1909, the Army purchased its first plane from the Wright Brothers for $25,000.

For the next several years, Army officers tended to view the airplane as merely a tool to assist ground operations rather than as an offensive force in itself. The Federal Government shared this view and did not assign funds to further military aviation. More than a decade after the first flight, when the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, military aviation was still practically non-existent. America's involvement in World War I provided the impetus for expanding the aircraft industry and military aviation.

When the United States entered the war, Germany had much more advanced aviation capabilities. To counter this, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Aviation Act in 1917, which budgeted more than $600 million to build up America's aviation program. The Army initially used military planes strictly to gather information about the enemy's positions. Soon, however, the United States produced more advanced airplanes capable of attacking enemy aircraft with machine guns and dropping bombs on selected targets. On May 24, 1918, the Aviation Section (formerly the Aeronautical Division) became separate from the Signal Corps and was renamed the United States Army Air Service. During the War, Air Service aircraft dropped roughly 115 tons of bombs during more than 200 bombing attacks.1 The Service downed more than 750 enemy aircraft, while losing less than 300 of its own. When the United States and its allies defeated Germany and the other Central Powers on November 11, 1918, the Air Service included 20,000 officers, 170,000 men, and 740 aircraft.2

After the war, the Air Service dramatically reduced its strength as funding dropped. Although some airmen argued that air power should form the core of the nation's military program, most politicians and military leaders agreed that the Service should continue to support ground troops as part of the Army. The most vocal advocate of air power was Brigadier General William "Billy" Mitchell, an Army pilot and Chief of the Air Service. He argued that airplanes could do more than spy on enemy troops or shoot down enemy planes. In fact, he proved that airplanes could destroy huge battleships that were once thought unsinkable. Although he faced much resistance within the military, Mitchell continually lobbied for increased air power. On July 2, 1926, the Air Service was expanded and renamed the United States Army Air Corps. During the 1920s and 30s, many advances in military as well as commercial airplanes took place.

In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe as Germany invaded Poland. Attacks by the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, on other European countries over the next year proved that air power was devastatingly effective. Aware of the events unfolding in Europe, the United States government called for rapid expansion of the Air Corps. Air Corps personnel increased from about 21,000 in 1938 to 354,000 by the end of 1941, when the Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the war.3

A few months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Army had upgraded the Air Corps to the United States Army Air Forces. Headed by General Henry "Hap" Arnold, the Army Air Forces had gained considerable autonomy, if not independence. By the end of World War II, United States aviation production was the largest industry in the world. With more than two million men and 80,000 planes, it also was the largest air force in the world.4

Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, but the Japanese government was determined to continue fighting. Rather than risk losing thousands of lives invading Japan, President Harry Truman authorized the use of the newly-developed atomic bomb. On August 6 , the B-29 Enola Gay dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, killing more than 300,000 people. A few days later another bomb destroyed the city of Nagasaki. The war ended with Japan's surrender on September 2, 1945. Air power had forever changed the way in which wars would be fought. The B-29, which played such a critical role in the victory, became a symbol of America's air power supremacy.

After the war, President Harry Truman called for a reorganization of the military. On July 26, 1947, he signed the National Security Act into law. This Act created the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the National Security Council. It also called for the Air Force, Army, and Navy to be equal under a new Department of Defense. On September 18, 1947, W. Stuart Symington became the first Secretary of the Air Force, and air activities were officially transferred from the Army to the new Department of the Air Force. After 40 years under the Army, the Air Force had at last achieved full independence.

Questions for Reading 1

1. When was the first air division created? What military service was it placed under?

2. How did World War I impact the United States' military aviation program? How did the Army first use airplanes in World War I? How did this change over time?

3. Why do you think military and political leaders were initially reluctant to expand the use of airplanes beyond support for ground troops?

4. How did World War II impact the United States' military aviation program?

5. When and how did the United States Air Force become an independent service?

Reading 1 was compiled from George V. Fagan, The Air Force Academy: An Illustrated History (Boulder, Col.: Johnson Books, 1988); Nancy Warren Ferrell, The U.S. Air Force (Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company, 1990); Bernard Fitzsimons, U.S. Air Force (New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1985); and Bill Yenne, The History of the U.S. Air Force (New York: Exeter Books, 1984).

¹ Bernard Fitzsimons, U.S. Air Force (New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1985), 13.

2 Ibid.

3 Bill Yenne, The History of the U.S. Air Force (New York: Exeter Books, 1984), 26.

4 Ibid., 37.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The Cold War Begins

Following World War II, the United States entered into a prolonged conflict with the Soviet Union known as the Cold War. Rather than involving direct combat, the Cold War was characterized by political tension and distrust, arms competition, and the threat of nuclear attack. Although allies during World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union held very different political, economic, and social views. Whereas the United States practiced democracy and capitalism, the Soviet Union was a Communist country ruled by a dictator.

According to Communist principles, the state should control the economy and the lives of citizens. The Soviet Union wanted to spread Communism to other countries, and the United States wanted to contain it within the countries where it already existed.

Tension evolved as the victorious Allied nations discussed the future of Europe, which had been physically and economically devastated by the war. It quickly became apparent that the Soviet Union had a different agenda than the United States, Great Britain, and France. The Soviet Union's goals included protecting its borders from future attacks by establishing pro-Soviet governments in Eastern Europe and keeping the defeated countries of Germany and Japan weak. The United States wanted to promote future peace and allow European countries to choose their own form of government.

By early 1947, the year the Air Force became an independent service, tension between the United States and the Soviet Union led to a change in foreign policy. To protect the United States' role as a world leader, President Truman wanted to prevent the Soviet Union from spreading Communism beyond its post-World War II boundaries. He declared that the United States must assist any nations struggling to prevent a Communist takeover. This policy, known as the Truman Doctrine, justified the use of the military to prevent the spread of Communism. Under the new Marshall Plan, the United States also gave billions of dollars in aid to countries trying to recover from the war. The Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan formed key elements in the United States' Cold War policy known as "containment."

Undaunted by Truman's policies, the Soviet Union continued to use its 10-million strong army to expand its "sphere of influence." The German capital of Berlin became a hot zone in Soviet-US relations. Following World War II, the four Allied nations had agreed to each control a portion or zone of Germany. They further divided the capital city of Berlin, which was located within the Soviet's zone. The United States, France, and England occupied the western section of the city, while the Soviet Union controlled the eastern portion of the city. In June 1948, the Soviets tried to gain control of the entire city by blockading rail, water, and roadways into West Berlin. The Soviets hoped that a lack of food and supplies would force West Berlin residents to comply. The Western Allies combated the blockade by flying supplies into the city. During the Berlin Airlift, the United States Air Force delivered food, clothing, medicine, and other supplies to two million West Berlin residents. After 462 days and nearly 200,000 flights, the Soviets lifted the blockade. Air power had effectively prevented a Communist takeover of West Berlin, and the new Air Force had successfully met its first Cold War challenge. Not surprisingly, the relationship between the world's two superpowers continued to deteriorate.

In June 1950, war broke out in Korea when Communist North Korean troops invaded South Korea. When the United Nations declared this act a violation of international peace, the United States and several other countries sent troops and supplies to aid South Korea's fight against a Communist takeover. The Soviet Union and China aided the North Korean troops. This was the first war in which both sides used jet planes. The Communist forces flew MiG-15 fighters and the United Nations' forces employed F-86 Sabres. During the three-year conflict, U.S. Air Force pilots shot down approximately 800 MiGs, while losing only about 80 Sabres. The Korean War, which had sparked an enormous increase in the armed forces, ended with a cease-fire in 1953. The war had prevented Communist expansion, but the original boundary dividing South Korea and Communist North Korea remained.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces during World War II, became President of the United States in 1953 as the Korean War was ending. He was determined to stop Communist expansion without hurting the nation's economy with massive military spending like the Truman Administration. He also wanted to avoid future regional conflicts like Korea, which had cost thousands of lives and was very unpopular with the public. He adopted what came to be known as the "New Look" policy. According to this policy, the nation's defense would rely on nuclear weapons and air power. Maintaining an arsenal of nuclear bombs would be cheaper than maintaining a large peacetime military force. The United States claimed it would counter Communist aggression anywhere in the free world with atomic strikes. This warning, backed up by nuclear capability, was intended to minimize the possibility of Soviet aggression. Eisenhower stated, "We shall not be aggressors, but we and our allies have and will maintain a massive capability to strike back."1

Using the threat of "massive retaliation" as the nation's primary defense plan necessarily pushed the Air Force to the forefront. According to this policy, the first line of defense would be an air atomic strike force. Eisenhower's plan called for large cuts in the Army and Navy's budget. The Air Force, however, would receive an $800 million increase in order to create an air force superior to any in the world. Although it was the newest service, the Air Force emerged as the United States' primary military arm during the first decade of the Cold War. As General Thomas D. White, Air Force vice chief of staff, claimed, the Air Force "had been recognized as an instrument of national policy."2

Questions for Reading 2

1. How would you define the Cold War? What made it "cold"? Based on the political, economic, and social differences between the United States and the Soviet Union, do you think that the Cold War was inevitable? Explain your answer.

2. What were the Soviet Union's primary goals after World War II? What was the Truman Doctrine? How would you define "containment"?

3. How did the Allies use air power creatively in response to the Soviet Union's blockade of West Berlin? What was the result?

4. Why did the United States send troops to South Korea? What was the result?

5. Why did Eisenhower create his "New Look" policy and how did it differ from Truman's approach to stopping the Communist threat? What was the impact of the "New Look" policy on the Air Force?

Reading 2 was compiled from Walter J. Boyne, Beyond the Wild Blue: A History of the U.S. Air Force, 1947-1997 (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997); George V. Fagan, The Air Force Academy: An Illustrated History (Boulder, Col.: Johnson Books, 1988); Bernard Fitzsimons, U.S. Air Force(New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1985); Leila M. Foster, The Story of the Cold War (Chicago: Childrens Press, Inc., 1990); Daniel J. Hoisington, "United States Air Force Academy, Cadet Area" (El Paso County, Colorado) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2003; Jeremy Isaacs and Taylor Downing, Cold War: An Illustrated History, 1945-1991(Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1998); Herman S. Wolk, "The 'New Look,'" Air Force Magazine, August 2003, Vol. 86, No. 8; and Bill Yenne, The History of the U.S. Air Force (New York: Exeter Books, 1984).

1 Herman S. Wolk, "The 'New Look,'" Air Force Magazine, August 2003, Vol. 86, No. 8.

2 Ibid.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Air Force Academy Becomes a Reality

America's defense policies during the early Cold War years necessitated a major expansion of the Air Force. The Service grew from 305,827 in 1947 to nearly 1,000,000 personnel by 1954. Accordingly, the Service needed approximately 1,200 new junior officers a year to fill its ranks.1 To meet the challenges of the complex nuclear age, the Air Force would require not only more, but better-educated officers.

As early as World War I, some Air Service officers felt that the Air Service should have an academy to train future officers. In 1918, Lieutenant Colonel A.J. Hanlon claimed, "As the Military and Naval Academies are the backbone of the Army and Navy, so must the Aeronautical Academy be the backbone of the Air Service. No Service can flourish without some such institution to inculcate into its embryonic officers love of country, proper conception of duty, and highest regard for honor."2 By 1925, the Army Air Service did have several training schools for its officers and enlisted personnel, but these were not comparable to the four-year college programs of West Point and the Naval Academy. In the years following World War II, several congressmen and senators introduced bills to establish an air academy in their state. None of these bills was acted upon, however.

After the Air Force became an independent department in 1947, it seemed that legislation for an academy finally could begin to take shape. In a 1948 report, Air Force Secretary Stuart Symington claimed, "The Air Force lacks an adequate source of officer personnel trained as professional Air Force officers from the beginning of their college careers. All leading professions recognize the requirement for formal college career training as the principal source of new blood in that profession. The Air Force is no exception."3

Selecting a suitable location for such an academy was an important step that proved to be a big stumbling block. Politicians and military leaders expressed many opinions on the subject, but no one seemed to agree. An Air Force Academy Site Selection Board, established in 1949, reviewed more than 300 sites in 22 states. The Board believed that a site near Colorado Springs, Colorado was the most appropriate. Their findings were not made public, however, and the quest for an academy languished again while the country focused on the Korean War.

When General Dwight Eisenhower became President in 1953, he renewed pressure for a separate air academy. On April 1, 1954, President Eisenhower signed the Air Force Academy Act. At last, after more than 30 years of struggle, an air academy would be established. As specified in the Act, Secretary of the Air Force Harold Talbott appointed five members to the new Air Force Site Selection Commission. The commission considered 580 proposals in 45 states. The members placed great emphasis on a site's natural beauty and its potential to provide a suitable setting for what would become a national monument.4 The commissioners visited and inspected 34 sites. In an official report of June 3, 1954, the commission narrowed the list to three sites: an area about eight miles north of Colorado Springs, Colorado; an area on the south shore of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin; and an area about 10 miles west of Alton, Illinois.

The residents of Colorado Springs were anxious to have the Academy located near their city. They believed that the Academy would help boost the city's economy, which had declined in the postwar period. The Chamber of Commerce and the Citizens Committee worked hard to prove that Colorado Springs was the best location. Their efforts were rewarded on June 24, 1954, when Secretary Talbott announced that Colorado Springs would become the permanent home of the Academy. Beginning in 1955, Denver, Colorado, served as the temporary site until the Colorado Springs location was ready.

The Federal Government and the Air Force considered the Academy's design extremely important. Secretary Talbott stated, "We want the Academy to be a living embodiment of the modernity of flying and to represent in its architectural concepts the national character of the Academy…. We want our structures to be as efficient and as flexible in their design as the most modern projected aircraft."5 The Air Force chose the nationally-recognized architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill Associates (SOM) to make its vision for the Academy a reality.

SOM's design embodied a new style of architecture that used glass, aluminum, steel, and concrete rather than traditional materials like stone, marble, or brick. Modern architecture also commonly organized space according to a regulated geometric grid or module. The design sparked heated debate and severe criticism. Many viewed it as inappropriate for a national monument. Others, however, recognized that the Academy's design was an appropriate representation of the work of the Air Force. The Academy's buildings would be made of metal just like the jet airplanes and missiles that were hallmarks of the Air Force itself. The New York Herald Tribune praised the design saying, "Just as West Point with its medieval fortress-like appearance symbolizes the traditions of land warfare, so does the sharp-lined and soaring Air Force Academy represent the newest and swiftest military science."6

The alternating ridges and valleys of the 18,500-acre Colorado Springs site created a design challenge. The Cadet Area, which forms the heart of the Academy and covers about a fifth of a square mile, was positioned atop the highest ridge with the spectacular Rampart Range serving as the backdrop. SOM's design called for two intersecting rectangular plazas surrounded by the Academy's principal buildings. The higher plaza, the Court of Honor, lies at an elevation of 7,176 feet above sea level. This generally open, paved space is dominated visually by the striking Cadet Chapel. A gently sloping ramp leads down to the slightly lower plaza, known as the Terrazzo. This large, open area is used for daily musters of the cadets. The relatively even terrain in the surrounding valleys (about 70 feet below the Court of Honor) was used for the athletic fields and parade ground. Although the scale of the project was monumental, SOM carefully planned the Cadet Area so that all activities—meals, classes, athletics, parade grounds, worship space—were within a 10-minute walk of the Academy's only dormitory. Air Force officers considered this important because the cadet's rigorous daily routine left little spare time.

On August 29, 1958, 1,145 cadets moved from temporary quarters in Denver to the Colorado Springs site. Although many of the structures were still under construction, this allowed the Academy's first graduating class to spend their final year at the new site. After completing four years at the Air Force Academy, cadets graduate with a bachelor of science degree and a commission as a second lieutenant in the Air Force. The Academy quickly became a major source of the officers needed to fill the ranks of the Air Force as it expanded under the nation's defense policies. Through rigorous academics and military training, the Academy instilled in these officers the knowledge and leadership qualities necessary to meet the challenges of Cold War era.

Even before it was established, the military, politicians, and the public understood that the Air Force Academy would become a national monument much like the campuses of West Point and the Naval Academy. Although controversial at first, the Air Force Academy design gained public acceptance and is now one of Colorado's chief tourist attractions.7 As Robert Bruegmann, a professor at the University of Illinois, stated, "It is one of the grandest…most intact ensembles of that era to be seen anywhere in the world. It functions as one of the great monuments of an era that seems so near to us in time but in other ways appears to belong to a past almost beyond recall."8 The Air Force Academy is a proud symbol not only of the Air Force's role in the nation's defense, but also of the modern movement in architecture that characterized the early Cold War era.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Why did the Air Force need so many new officers in the early 1950s?

2. What were some of the obstacles that prevented the establishment of an Air Force academy? When was the Air Force Academy finally approved?

3. What were Secretary Talbott's goals for the Academy's design? Why was SOM's design controversial? Do you think SOM met Talbott's goals?

4. Why do you think planners wanted to pick a site that was "monumental" in nature? Was that consistent with the visions of Hanlon and Talbott? Why or why not?

5. What do you think Robert Bruegmann meant by his quote?

Reading 3 was compiled from George V. Fagan, The Air Force Academy: An Illustrated History (Boulder, Col.: Johnson Books, 1988); and Daniel J. Hoisington, "United States Air Force Academy, Cadet Area" (El Paso County, Colorado) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2003.

1 Daniel J. Hoisington, "United States Air Force Academy, Cadet Area" (El Paso County, Colorado) National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2003, 25.

2 George V. Fagan, The Air Force Academy: An Illustrated History (Boulder, Col.: Johnson Books, 1988), 6.

3 As quoted in Hoisington, 21.

4 Hoisington, 23.

5 Testimony of Harold E. Talbott, Secretary of the Air Force, U.S., Congress, House of Representatives, Hearings before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, 84th Congress, 1st session, 1955, 224. As quoted in Hoisington, 29.

6 New York Herald Tribune, May 16, 1955. As quoted in Hoisington, 37.

7 Fagan, 150.

8 Hoisington, 43.

(Courtesy Colorado Springs Chamber of Commerce)

Colorado Springs residents had campaigned to bring the Academy to their city since 1949, when the first Academy Site Selection Board was formed. The Colorado Springs Committee presented this brochure (and many others) to the Site Selection Commission to convince the members to choose their city. As one reporter stated in July 1954, "It was neither politics nor propaganda that brought the United States Air Force Academy to Colorado, but the excellence of the site and the quiet persistence of Colorado Springs leaders who had been working on the project for six years."1

Questions for Illustration 1

1. Why were Colorado Springs residents anxious to have the Air Force Academy in their area? (Refer back to Reading 3, if necessary.)

2. Based on the illustration, what features of Colorado Springs did the committee try to emphasize?

3. What do you think the image of the cadets was intended to convey?

4. Look up the words "booster" and "boosterism." Do you think this brochure cover is an example of boosterism? Explain your answer.

1 Christian Science Monitor, July 1954. As quoted in George V. Fagan, The Air Force Academy: An Illustrated History (Boulder, Col.: Johnson Books, 1988), 48.

Visual Evidence

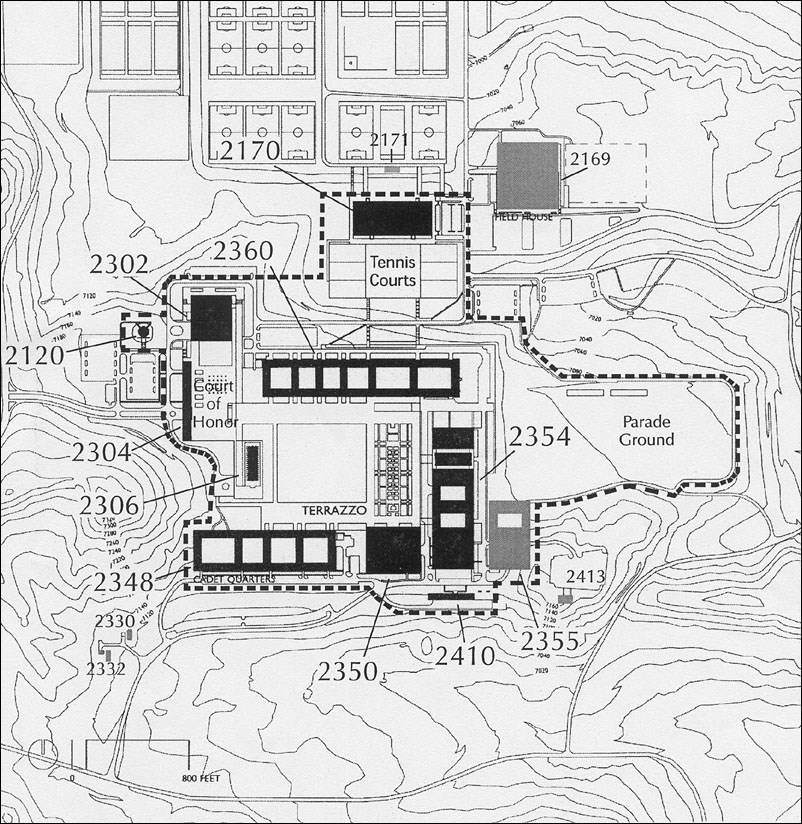

Drawing 1: Plan of the Cadet Area.

Key

2170—Physical Education Building

2302—Arnold Hall: cadet social hall

2304—Harmon Hall: administration building

2306—Cadet Chapel

2348—Sijan Hall (added in 1968): cadet quarters

2350—Mitchell Hall: dining facility

2354—Fairchild Hall: primary academic building

2360—Vandenberg Hall: cadet quarters

2410—Aerospace Laboratory

While most American college campuses had been built piece by piece as the institution grew, the Air Force Academy was largely planned and constructed all at once.

Questions for Drawing 1

1. The contour lines on Drawing 1 show changes in elevation. What can you learn about the topography of the site by studying the drawing?

2. Locate Vandenberg Hall. This 1,337-foot long building contained 1,320 rooms capable of housing 2,640 cadets. Why might Air Force officers have wanted all cadets to live in the same dormitory? How did SOM's layout of the Cadet Area take into account the cadets' busy schedule?

3. What can you learn about cadet life by studying the drawing and key?

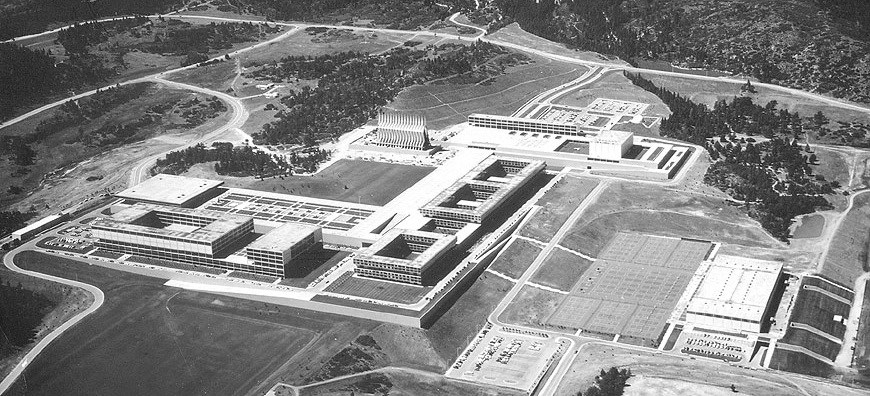

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Aerial view of the Air Force Academy, ca. 1962.

More than 300 architectural firms applied for the Air Force Academy commission. By 1954, Skidmore, Owings and Merrill was one of the few American design firms that was large enough to complete a project on the scale of the Academy within a short time span. The firm represented the "modern movement" in architecture, which rejected the use of traditional building materials in favor of structural steel and glass. The resulting designs featured clean, straight lines with minimal or no decorative details. Consistent with modern architecture design principles, SOM applied a seven-foot grid or module to the entire Cadet Area. This meant that the dimensions and layout of buildings as well as landscape features were based on 7-foot increments.

Questions for Photo 1

1. Using the key from Drawing 1, identify as many parts of the Cadet Area as you can in the photo.

2. Which building shown on Drawing 1 does not appear in Photo 1? Why? How did the new building impact the layout of the campus?

3. How would you describe the campus? How would you describe the surroundings?

4. What do you think would be the advantages and disadvantages to designing buildings and spaces using a rigid grid system?

Visual Evidence

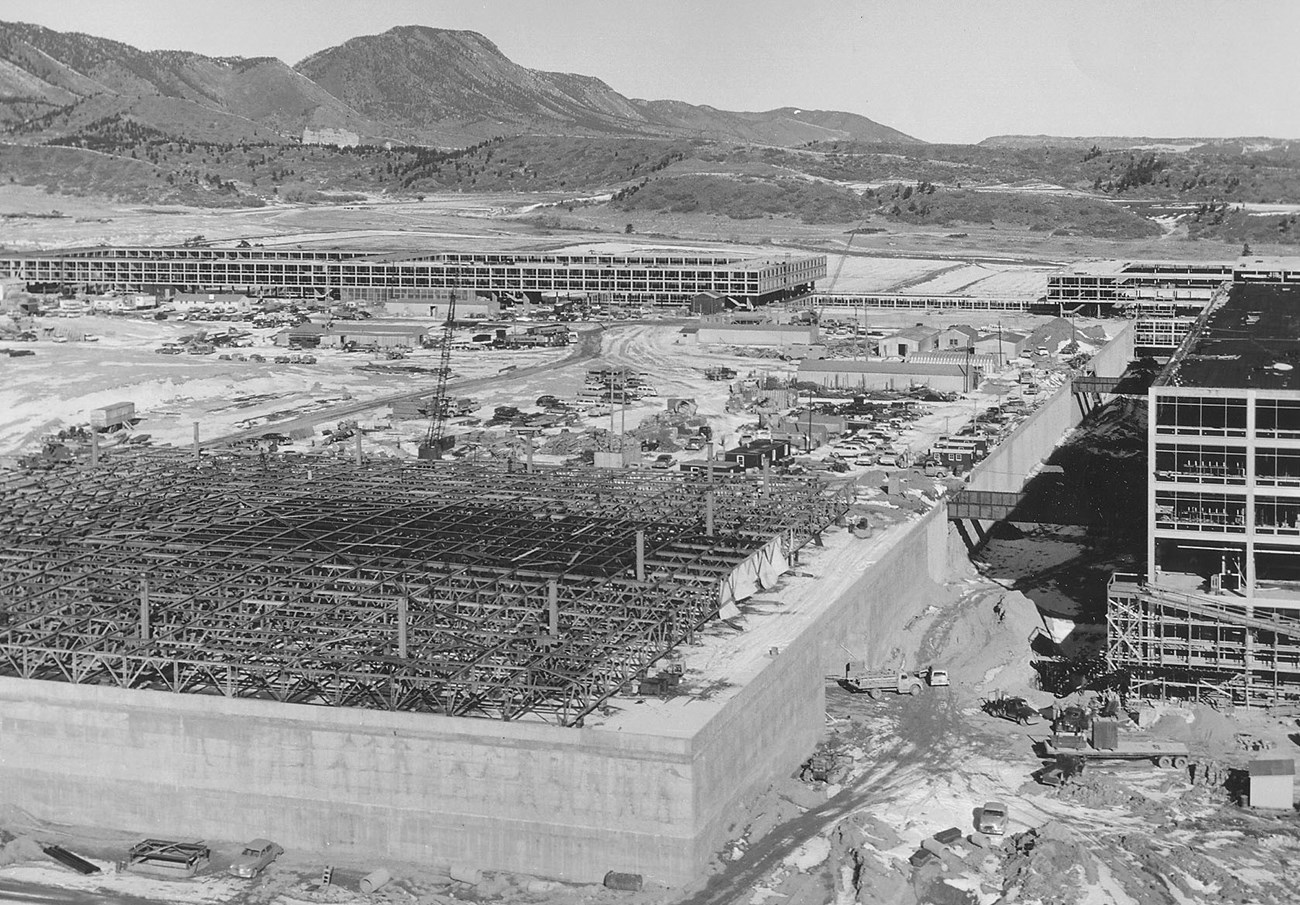

Photo 2: Mitchell Hall under construction, ca. 1958.

When ground was broken in 1955, the Academy was the largest single educational building program ever undertaken in the United States. More than 5,000 workers were employed by 20 major construction firms. Mitchell Hall, the cadet dining facility, is located on the Terrazzo. In this photo, workers are preparing the steel truss roof structure to be raised. The completed building was roughly 308 feet by 308 feet.

Questions for Photo 2

1. Identify Mitchell Hall on Drawing 1 and Photo 1. Who was this building named after? (Refer back to Reading 1, if necessary.)

2. Does this photo help you to understand the scale of the Academy project? If so, how?

3. What can you learn about the building materials and construction techniques from studying this photo?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Cadet Area.

(USAFA)

Photo 3 is a view to the south with the Rampart Range in the background. The topography of the Academy site required extensive preparations including the construction of concrete retaining walls and earthen embankments to create artificial terraces at the crest of the ridge where the Cadet Area was placed.

Questions for Photo 3

1. Using the Chapel as a guide, match Photo 3 to Drawing 1. Does the photo help you to understand the contour lines shown in Drawing 1? If so, how?

2. How does this photo add to your understanding of the site and the setting? What evidence can you find of "terracing"? Why was this necessary?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Basic cadets, August 1958.

(USAFA, Special Collections)

Photo 4 shows basic cadets climbing a ramp to the Terrazzo Level of the Cadet Area. Skidmore, Owings and Merrill used the Air Force Academy project to test new technology and building materials. Because of the extensive use of glass (more than one million square feet) and the sunny climate, the firm convinced glass makers to produce a gray tinted glass to absorb heat and light. SOM also experimented with anodizing the aluminum to prevent discoloration and used new finishing techniques for the granite covering the huge retaining walls.

Questions for Photo 4

1. What new technologies did SOM use for the Air Force Academy project? What evidence of these can you find in the photo?

2. In your own words, how would you describe the architectural style of the building shown in the photo?

3. What are the cadets doing in this photo? Why do you think the cadets at the top of the ramp are dressed differently than those marching up the ramp?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Interior of Mitchell Hall, ca. 1962.

(USAFA, Special Collections)

SOM designed Mitchell Hall to seat the entire Cadet Wing (nearly 3,000 students) at one time. The dining hall is a vast open space with a 24-foot ceiling. A mezzanine level provided seating for senior personnel and quests. Mitchell Hall was expanded in 1966 to accommodate an additional 1,000 cadets.

Questions for Photo 5

1. What can you learn about cadet life from studying this photo?

2. Identify the mezzanine level. What was it used for? What other uses can you think of for this space?

3. Why do you think the hall was designed to seat all the cadets at one time? How difficult do you think it would have been to prepare and serve meals for 3,000 people simultaneously?

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Cadet Chapel.

(USAFA)

The Chapel, completed in 1963, is the focal point of the Cadet Area. Its unique design was widely criticized by the public and politicians at first. With its 17 aluminum spires soaring 150 feet into the air, the Chapel has become a symbol of the Air Force Academy. The interior provides three distinct worship areas: the Protestant Chapel, the Catholic Chapel, and the Jewish Chapel.

Questions for Photo 6

1. Why do you think the Chapel received so much negative publicity at first?

2. In your own words, how would you describe the Chapel? Do you think it is an appropriate worship space? Why or why not?

3. Reread the quote by Secretary Talbott in Reading 3 regarding his vision for the Academy. Do you think the Chapel's design reflected his goals? Why or why not?

Air Force Academy--

Supplementary Resources

By studying The United States Air Force Academy: Founding a Proud Tradition students learn how the expansion of military air power in the first half of the 20th century led to the establishment of the United States Air Force and the Air Force Academy. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

The United States Air Force Academy

The Air Force Academy website lists the Academy's mission and core values and provides information on cadet life.

The United States Air Force

The Air Force website contains detailed information on Air Force history as well as current activities. The History page provides an overview of the Air Force's heritage, important people, air power, images, milestones, and art.

The United States Air Force Museum

The United States Air Force Museum, located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, portrays the history and traditions of the United States Air Force through specialized displays and exhibition of historical items. The Museum's website features information on military aircraft from the 1909 Wright Military Flyer to those used by the Air Force today.

National Archives and Records Administration

Use the Archival Research Catalog page of the National Archives web site to search for Air Force-related resources. Of particular interest is a digital copy of the Air Force Academy Act of April 1, 1954, which established the United States Air Force Academy. To locate, click on the "ARC Search" button and enter "299866."

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress's on-line exhibit of Soviet Archives includes a detailed analysis of Soviet-American relations and translations of Soviet primary documents.

The Cold War Museum

The Museum's website features a time line by decade with links to essays, images from museum exhibits, and a photo gallery.