As the Confederates moved toward the Potomac River and Maryland, President Abraham Lincoln and the Union Army scrambled to counter them. A conglomerate of all the forces in the Washington vicinity were thrown together. Some of its men were fresh from the recruiting depots--they lacked training and were deficient in arms. Others had just returned from the Peninsular Campaign where Lee's army had driven them from the gates of Richmond in the Seven Days' Battles. Still others were the remnants of the force decisively beaten at the Second Battle of Manassas.

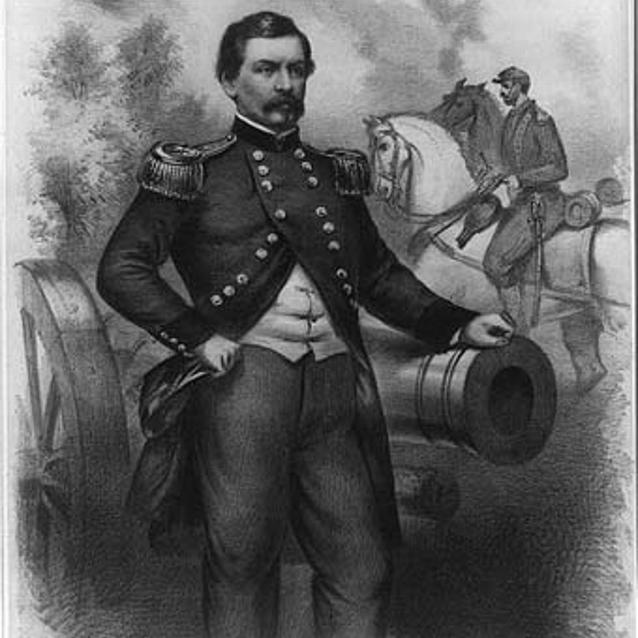

"Nothing but a desire to do my duty could have induced me to accept the command under such circumstances." General George McClellan

Critical Timing

Library of Congress

At the head of this army, Lincoln placed Gen. George B. McClellan. At this critical moment, the army needed organization and confidence, two things McClellan was well acquainted with. In four days, he pulled together the army and prepared it to march, ready to pursue Lee. It was a remarkable achievement.

But in other respects, McClellan was the object of doubt. He was cautious. He seemed to lack that capacity for full and violent commitment essential to victory. Against Lee, whose blood roused at the sound of the guns, McClellan's methodical nature had once before proved wanting. Lincoln understood this, but knew that he had no better option for command, saying:

"He had beyond any officer the confidence of the army. Though deficient in the positive qualities which are necessary for an energetic commander, his organizing powers could be made temporarily available till the troops were rallied."

A victory in the field would give the President a chance to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which he had been holding since mid-summer. The proclamation would declare the slaves in the states in rebellion "thenceforward and forever free". Unless this moral purpose could be added to the North's primary war aim of restoring the Union, Lincoln questioned whether the will to fight could be maintained in the face of growing casualty lists.

Followed by mingled doubt and hope, McClellan started in pursuit of the Confederate army. He knew Lincoln and Halleck had come to him as a last resort in a time of emergency. He knew they doubted his energy and ability as a combat commander. Even his orders from them were unclear, they did not explicitly give him authority to pursue the enemy beyond the defenses of Washington.

Burdened with knowledge of this lack of faith, wary of taking risks because of his ambiguous orders, McClellan marched toward his encounter with the victorious and confident Lee.

Part of a series of articles titled A Savage Continual Thunder.

Previous: Confederates Taking Charge

Next: Leading the Charge

Tags

Last updated: February 3, 2015