Last updated: April 12, 2023

Article

The Siege and Battle of Corinth: A New Kind of War (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

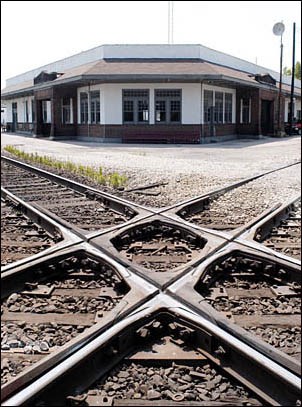

The tracks still cross in the center of town, and trains still use them, but no one fights over them any more. During the Civil War as many as 300,000 soldiers moved through this tiny town in northeastern Mississippi as the Union and the Confederacy fought to control a critical railroad crossover. The evidence of their presence is everywhere. A reconstructed earthen redoubt commemorates the men in grey who marched with slow and steady steps against its walls and the men in blue who defended it in fierce hand-to-hand combat. And if you look carefully, you can see miles and miles of earthen fortifications, some built to protect the crossover and some to help seize it. These trenches testify to a new kind of warfare that was tested here and would become common before the war ended in 1865.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Siege and Battle of Corinth" (with photographs); on Peter Cozzens, The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997); on Margaret Greene Rogers, Civil War Corinth, 1861-65 (Corinth, MS: Rankin Printery, 1989); and on material prepared for the Siege and Battle of Corinth Commission. It was made possible by the National Park Service's American Battlefield Protection Program. The lesson was written by Jenniffer Wamsley, education specialist at Shiloh National Military Park and elementary teacher in Corinth, and Gloria Cartwright, secondary social studies teacher with the Corinth City Schools. It was edited by Fay Metcalf, an education consultant living in Mesa, Arizona; by Kathleen Hunter, an education consultant living in Hartford, Connecticut; by Marilyn Harper, a National Park Service consultant; and by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. The lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: lesson could be used in units on the Civil War or in courses on technology.

Time period: Civil War

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

The Siege and Battle of Corinth: A New Kind of War

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

Standard 2A- The student understands how the resources of the Union and Confederacy affected the course of the war.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

The Siege and Battle of Corinth: A New Kind of War relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals daily lives.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard D - The student describes the way nations and organizations respond to forces of unity and diversity affecting order and security.

-

Standard F - The student explains, actions and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among organizations.

-

Standard G - The student describes and analyzes the role od technology in communications, transportation, information-processing, weapons development, and other areas as it contributes to or helps resolves issues.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology and Society

-

Standard A - The student examines and describes the influence of culture on scientific and technological choices and advancement, such as in transportation, medicine, and warfare.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard B - The student analyze examples of conflict, cooperation, and interdependence among groups, societies, and nations.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard D - The student practice forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

Objectives for students

1) To explain why gaining control of the railroads in Corinth was important to both the Union and the Confederacy.

2) To describe the course of the Siege of Corinth and the Battle of Corinth and to evaluate their impact on the course of the Civil War.

3) To describe the fortifications constructed during these engagements and to analyze their importance.

4) To examine the role transportation routes played in the formation of the student's own community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

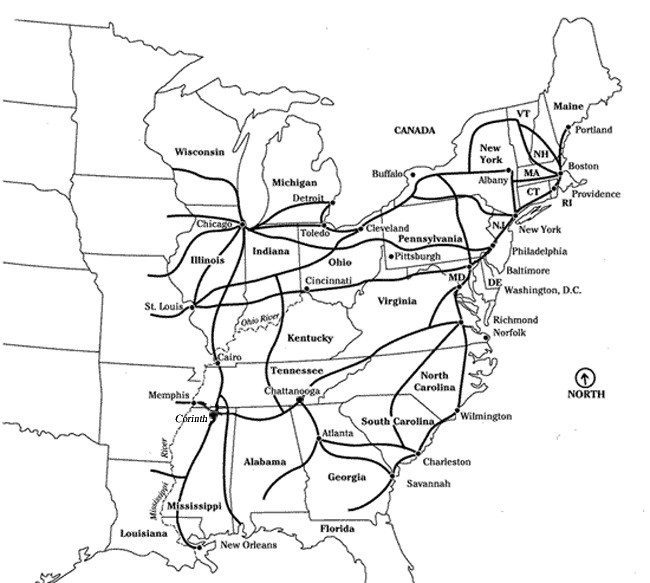

1) one map showing major railroads in 1860;

2) three reading about the siege and battle and about fortifications;

3) four illustrations showing entrenchments and Corinth after the Siege;

4) four illustrations showing Corinth and the aftermath of the battle.

Visiting the site

Corinth is located in northeastern Mississippi, approximately 22 miles southwest of Shiloh, Tennessee, on Highway 22. The historic crossover of the Memphis and Charleston and the Mobile and Ohio Railroads is represented today by the crossing of the Illinois Central Gulf and the Southern Railroads at the western edge of town.

Remnants of the extensive earthworks and fortifications built by the Confederate and Union armies are scattered throughout the landscape surrounding Corinth. A Corinth Civil War Interpretive Center, operated by the National Park Service as part of Shiloh National Military Park and located at the historic location of Battery Robinett on Linden Street, is open from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and is closed only on December 25th. For more information, contact the center at 662-287-9273. For further information on the center and on Civil War sites in Corinth and the surrounding communities in northeast Mississippi, contact Shiloh National Military Park, 1055 Pittsburg Landing Road, Shiloh, Tennessee 38376 (call 731-689-5696), or visit the park's website.

The Northeast Mississippi Museum, located one block west of Business Highway 45 at 45 North Fourth Street in Corinth, contains Civil War artifacts and historical images. Call the museum (662-287-3120) for open hours. Additional information can be obtained by writing the Northeast Mississippi Museum Association, P.O. Box 993, Corinth, MS 38834.

Setting the Stage

Many military historians consider the American Civil War the first modern war. Both Confederate and Union officers sought ways to use the railroads and the new rifled weapons, the most modern technologies of their day, both for their own advantage and to protect themselves against these same technologies being employed by their enemies. In two separate engagements in late April-May and in October of 1862, the town of Corinth, Mississippi, gave both sides training in the "new warfare."

Things were not going well for the Confederacy in early 1862. In the east, Union armies were threatening Richmond, VA. Union naval forces took New Orleans, LA, the Confederacy's largest city and most important port. The Confederates were forced to abandon southern Kentucky and much of West and Middle Tennessee. A large Federal force, under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, was moving down the Tennessee River towards the railroad crossover at Corinth.

Corinth was established in the 1850s at the crossing of the Memphis and Charleston and the Mobile and Ohio railroads. By 1862, it was a small town, with a population of about 1200 people. Tishomingo County (later becoming Alcorn County) had opposed secession in early January, but now Corinth was full of Confederate soldiers. The railroads had rushed nearly 40,000 men to the town, from places as far away as Florida, Kentucky, and New Orleans. On April 3, they moved out to head Grant off before he could strike. After almost succeeding at the bloody Battle of Shiloh, near Pittsburg Landing in Tennessee, they returned to Corinth. In spite of terrible losses on both sides, the Confederates had not stopped the Union's advance. They settled down to collect their forces, dig in, and wait.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate the town of Corinth and the two railroad lines that cross there. What cities do the railroads connect? How many other long railroad lines can you identify? How many of them are in the South?

2. What can you infer from this map about the importance of Corinth's railroads to the Confederacy?

3. What other railroad junctions can you identify in the South? How do you think they might compare with Corinth in importance?

4. What other methods of transportation can you think of that could be used to transport troops and supplies? What advantages and disadvantages would they have in comparison with the railroads?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Siege of Corinth

At the end of April, 1862, a Union Army group of almost 125,000 men, led by Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, set out from Pittsburg and Hamburg landings towards Corinth. A Confederate force of about half that size, under the command of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, waited for them, behind five miles of newly-constructed earthworks. Both commanders knew the importance of the coming battle. Halleck claimed that the railroad centers in Richmond, Virginia, and Corinth were "the greatest strategic points of the war, and our success at these points should be insured at all hazards." Beauregard told his superiors: "If defeated here we will lose the Mississippi Valley and probably our cause . . . [and] our independence."1

It took Halleck a month to travel the 22 miles to Corinth. The route crossed a series of low ridges covered with dense forests and cut by stream valleys and ravines. Moving his army through rugged country while keeping it aligned along a 10-mile front was slow and difficult work. The weather was bad and there was little good water. Dysentery and typhoid were common.

By May 4, the Union army was within 10 miles of Corinth and the railroads. The Confederates began a series of small scale attacks, keeping up a nearly constant harassment. Halleck, cautious by nature, established an elaborate procedure to protect his army as they advanced. As the troops moved up to a new position, they worked day and night digging trenches. These "were made to conform with the nature of the ground, following the crest of the ridges. . . . They consisted of a single ditch and a parapet . . . only designed to cover our infantry against the projectiles of the enemy."2 As each line of earthworks was finished, the men advanced about a mile and then started digging a new line of trenches. Eventually there were seven progressive lines and about 40 miles of trenches.

The Confederates waiting in Corinth were well aware of Halleck's slow, but constant, advance. In May, a Confederate soldier wrote his wife:

I can sit now in my tent and hear the drums & voices in the enemy lines, which cannot be more than two miles distant. We have . . . killed and wounded every day. . . . The Yanks are evidently making heavy preparation for the attack which cannot, I think, be postponed many days longer. . . . Everything betokens an early engagement so make it be, for I am more than anxious that it shall come without further delay.3

On May 21, Beauregard planned a counterattack, an attempt to "draw the enemy out of his entrenched positions and separate his closed masses for a battle."4 The gamble came to naught because of delays in getting the troops in position to attack.

By May 25, the long Union line was entrenched on high ground within a few thousand yards of the Confederate fortifications. From that range, Union guns shelled the Confederate defensive earthworks, and the supply base and railroad facilities in Corinth. Beauregard was outnumbered two to one. The water was bad. Typhoid and dysentery had felled thousands of his men. At a council of war, the Confederate officers concluded that they could not hold the railroad crossover.

Beauregard saved his army by a hoax. Some of the men were given three days' rations and ordered to prepare for an attack. As expected, one or two went over to the Union with that news. During the night of May 29, the Confederate army moved out. They used the Mobile and Ohio Railroad to carry the sick and wounded, the heavy artillery, and tons of supplies. When a train arrived, the troops cheered as though reinforcements were arriving. They set up dummy ("Quaker") guns along the defensive earthworks. Camp fires were kept burning, and buglers and drummers played. The rest of the men slipped away undetected. When Union patrols entered Corinth on the morning of May 30, they found the Confederates gone.

Most historians believe that the Union seizure of the strategic railroad crossover at Corinth led directly to the fall of Fort Pillow on the Mississippi, the loss of much of Middle and West Tennessee, the surrender of Memphis, and the opening of the lower Mississippi River to Federal gunboats as far south as Vicksburg. And no Confederate train ever again carried men and supplies from Chattanooga to Memphis.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why did it take so long for Gen. Halleck to move his Union troops to Corinth?

2. Why do you think Gen. Beauregard thought it was important to draw the Union forces "out of their entrenched positions"?

3. How did Beauregard and his generals deceive the Union army?

4. How did he make use of the railroads?

5. What were the consequences of the Confederate loss of Corinth?

Reading 1 was excerpted from Paul Hawke, Cecil McKithan, Tom Hensley, Jack Elliott, and Edwin C. Bearss, "Siege and Battle of Corinth" (Alcorn County Mississippi, and Hardeman County, Tennessee), National Historic Landmark documentation, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1991; and from Ray S. Price and Ellsworth R. Swift, "Civil War Corinth, Interpretive Concept Plan" (prepared for the Siege and Battle of Corinth Commission, 1995), 3-5.

1Halleck to Stanton, May 25, 1862, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series I, Vol. X, Part 1, 667; Beauregard to Samuel Cooper, April 9, 1862, O.R., I, X, 2, 403. (Subsequent citations will be identified as O.R., followed by series, volume, part, and page numbers).

2Stanley report, June 14, 1862, O.R., I, X, 1, 722.

3Letter, author unknown, May 23, 1862, Northeast Mississippi Museum, Corinth, MS.

4Beauregard, June 22, 1862, O.R., I, X, 1, 776.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The Battle of Corinth

After the Confederates evacuated Corinth, Union soldiers occupied the town. They spent most of the long, hot summer digging wells to find good water and building additional fortifications. Gen. Halleck ordered the construction of a series of larger earthwork fortifications called "batteries," designed to hold cannon to protect Corinth against Confederate forces approaching from the west or south. His successor, Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, concentrated on protecting the railroad crossover and its vital supplies. He built an inner series of batteries on the ridges immediately around the town. Trenches for infantrymen connected the batteries and masses of sharpened logs pointing outward (the Civil War equivalent of barbed wire) strengthened the line.

In the summer and early fall of 1862, the military situation changed dramatically. The South seized the initiative from Virginia to the Mississippi River and beyond. In hard-fought battles, the Confederates carried the fighting to the North. On the all-important diplomatic drawing room "front," the British government seemed on the verge of recognizing the Confederacy as an independent country.

In September, many of the men at Corinth went off to fight a bloody battle at Iuka, successfully blocking a Confederate move into Middle Tennessee. On October 2, Gen. Rosecrans learned that the Confederates were approaching from the northwest. The two armies each had 22,000-23,000 men, but Rosecrans's position behind his defensive earthworks was a strong one. He stationed his advance guard about three miles beyond the town limits. On October 3, Union and Confederate forces clashed initially in the area fronting the old Confederate earthworks. In heavy fighting throughout the day, the Confederates pushed Union forces back about two miles. Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, the Confederate commander, certain he could win an overwhelming victory in the morning, called a halt to the fighting about 6:00 p.m. His troops, parched and exhausted from lack of water and 90-degree heat, camped for the night, some only a few hundred yards from the inner fortifications where Union troops had taken refuge.

During the night, Union commanders moved their men into a more compact position closer to Corinth, covering the western and northern approaches to the community. The partially entrenched line was less than two miles long and was strengthened at key points by the cannons of the batteries named Tannrath, Lothrop, and Phillips located on College hill southwest of the town; batteries Williams and Robinett, positioned overlooking the cut of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad immediately west of the rail junction; and an unfinished Battery Powell, still being built on the northern outskirts of Corinth.

Before dawn on October 4, the Confederates woke the Union troops with artillery fire, but things quickly began to go wrong. The general who was to lead the opening attack had to be replaced, causing confusion and delay. But about 9:00 a.m. the Confederates opened a savage attack on the Union line. Some of the Confederates fought their way into the town. Battery Powell changed hands twice in fierce fighting. About 10:00 a.m., four columns of gray clad Confederates advanced on Battery Robinett. The men inside the battery watched them come:

As soon as they were ready they started at us with a firm, slow, steady, step. In my campaigning I had never seen anything so hard to stand as that slow, steady tramp. Not a sound was heard but they looked as if they intended to walk over us. I afterwards stood a bayonet charge . . . that was not so trying on the nerves as that steady, solemn advance.1

A man from an Alabama regiment described the scene from the Confederate side:

The whole of Corinth with its enormous fortifications, burst upon our view. The United States flag was floating over the forts and in town. We were met by a perfect storm of grape[shot], canister, cannon balls, and minie balls. Oh God! I have never seen the like! The men fell like grass.2

Four times they charged, each time being mowed down by withering fire from the cannons of batteries Robinett and Williams and from the muskets of the men lined up in the field next to the batteries. After desperate fighting, a Union bayonet charge broke the enemy columns and drove them back. By noon Van Dorn's army was in retreat. Rosecrans did not pursue the retreating army until the next day, and eventually Van Dorn managed to save his army. The Union lost 2,360 men killed and wounded in the fierce two-day fight; Confederates losses totaled 4,848. Union victories at Corinth, MS, Antietam, MD, and Perryville, KY set the stage for Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and helped prevent the British and the French from recognizing the Confederacy. The Confederacy never recovered from its losses of September and October 1862.

The Union continued to occupy Corinth for the next 15 months, using it as a base to raid northern Mississippi, Alabama, and southern Tennessee. Control of Corinth and its railroads opened the way for Union victory at Vicksburg, MS in July 1863. On January 25, 1864, Union troops left the town. The Confederates returned, but it was too late. The South had not built a single locomotive since 1861 and could no longer take advantage of the once critical railroad lines. The only cars moving on the patched-together tracks were pulled by mules.

Questions for Reading 2

1. How did Union forces try to prepare Corinth against a Confederate attack?

2. What changed during the summer of 1862?

3. What happened when the Confederates charged Battery Robinett? Why did the attack not succeed?

4. What were the consequences of the Confederate defeat?

5. Why was it too late when the Confederates returned to Corinth?

Reading 2 was adapted from Paul Hawke, et al., "Siege and Battle of Corinth" National Historic Landmark documentation; Ray S. Price and Ellsworth R. Swift, "Civil War Corinth, Interpretive Concept Plan," 6-7; Cozzens, The Darkest Days of the War and Rogers, Civil War Corinth, 27-40.

1Oscar L. Jackson, The Colonel's Diary (Sharon, PA: n.p., 1922), 71.

2Letter of Charles C. Labuzan, 1st Lieutenant, Co. F, 42nd Alabama, Grenville Dodge Papers, State Historical Society of Iowa, Des Moines.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Dirty Work of Fortifications

The use of military earthworks in the Civil War was on an unprecedented scale. Earthworks can be defined generally as any structure made of dirt for military purposes. Soldiers in the Civil War built earthworks for the same reasons Roman armies did: to protect an important place, to help a small number of defenders resist a larger number of attackers, or to surround and cutoff a place important to the enemy. Their forms and complexity evolved in response to improvements in weapons technology.

When the United States Military Academy was established at West Point in 1802, it was modeled after French military academies. Civil and military engineering were the cornerstones of the curriculum. Dennis Hart Mahan, who taught at West Point for 47 years, first published his Complete Treatise on Field Fortification, with the General Outlines of the Principles Regulating the Arrangement, the Attack, and the Defense of Permanent Works in 1836. In it he summarized current European theories of field fortification.

Many of these theories could be traced back to principles that were developed by military engineers in the 17th and 18th centuries in response to the introduction of gunpowder and moveable artillery. First, any fortification was only as strong as its weakest part. Each fortification should be built within range of adjacent fortifications so that they could provide mutual support. Cannoneers and infantrymen instinctively fire straight ahead, so every fortification had to have at least one section that faced each expected direction of attack. Each section was responsible only for the area immediately in front of it. There should be as little dead ground as possible, that is, areas that could not be fired on by guns inside the fortification. Earthworks were better at absorbing the impact of bullets and cannon balls than fortifications of stone or brick. Topography, above all else, drove design. Each fortification had to be uniquely designed for the particular piece of ground it occupied.

In the late 17th century, Louis XIV's chief military engineer, Sebastien de Vauban, developed a "scientific" method to use earthworks offensively. Men besieging a fortified position first constructed lines of earthworks facing the fortification, but beyond the range of its guns. During the night, they dug a zigzag trench leading towards the target and built another line at the new position. Once they got close enough, they hauled artillery forward to the protected position and bombarded the walls at close range, eventually opening the way for an infantry charge. Vauban often added an outer ring of interconnected and mutually supporting earthworks. These detached outer works were often used to protect storage depots, supply lines, and artillery batteries, and to slow the enemy's approach. It did not take many soldiers or cannons to man these earthworks, which could be quickly thrown up and as quickly abandoned.

Most earthworks were built before the battle began, but armies also erected entrenchments on the battlefield, primarily to protect artillery. At first, infantrymen relied on sunken roads, walled farmhouses, and other "found" defenses to protect themselves. By the early 19th century, some officers were ordering their men to dig in. Even a shallow parapet could deflect a bounding cannon ball up and over the heads of the soldiers lying behind it.

In the mid 19th century, weapons technology changed again, as European and American armies began to rely on mass-produced rifled weapons. Cutting spiral grooves into the inside of the barrels of cannon and muskets made them more powerful and more accurate at longer ranges. Rifle-muskets fired what the soldiers called a "minie ball," named after its innovator, Claude Etienne Minié. An experienced soldier could load and fire a rifle-musket as quickly as a smoothbore musket, and he could kill a man at 300 yards, three times the distance of the old smoothbores.

Rifle-muskets made warfare a much more dangerous business for infantrymen. Facing smoothbore muskets, an attacking army could approach within a hundred yards of a line of defenders without incurring serious losses and then make a last dash with bayonets. Attackers facing men armed with rifle-muskets could rarely cross that last hundred yards without losing so many men that they could no longer manage a decisive bayonet charge.

When the Civil War began, more than half of the Confederate and Federal units were armed with smoothbore muskets, but both sides soon equipped their front-line troops with rifle-muskets. Military theorists were still debating the lessons of rifled firepower and entrenchment, but Mahan's view was clear. In the introduction to his 1861 edition, he wrote: "The great destruction of life in open assaults . . . must give additional value to entrenched fields of battle."1 Nearly every West Point graduate who served in the Civil War on either side learned his fortification theory and methods from Mahan.

By 1864, all troops were regularly entrenching on the battlefield, as the spade replaced the bayonet. For the common soldier, entrenching was a rational response to the increasing deadliness of the battlefield--digging increased both his effectiveness and his odds of survival. European countries sent observers to the United States while the war was still going on to study the use of earthworks in places like Richmond, VA and Petersburg, VA. What they learned here, they used in World War I, where trenches defined that bloody conflict.

Questions for Reading 3

1. What were earthworks supposed to accomplish?

2. What principles of fortification did Civil War officers learn at West Point? How were they applied at the Siege of Corinth? at the Battle of Corinth?

3. How did the Siege of Corinth resemble Vauban's technique for attacking fortifications? How did it differ?

4. What change in offensive weapons occurred about the time of the Civil War?

5. A popular view held that:

At the beginning of the Civil War, the opinion in the North and South was adverse to the use of fieldworks, for the manual labor required to throw them up was thought to detract from the dignity of a soldier. . . . The epithet of dirt-diggers was applied to the advocates of entrenchments. Expressions were heard to the effect that the difference ought to be settled by a fair, stand-up fight in the open.2

Why do you think most Civil War soldiers disapproved of entrenching at the beginning of the war? Why did their opinion change?

Reading 3 was excerpted from David Lowe and Paul Hawke, "Military Earthworks-Historical Overview," typescript draft prepared for "Guide to Sustainable Earthworks Management," National Park Service, in association with the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation.

1Dennis Hart Mahan, A Treatise on Field Fortification (New York: John Wiley, 1851), v.

2Capt. E. O. Hunt, "Entrenchments and Fortifications," in Photographic History of the Civil War, Francis Trevelyan Miller, ed. (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1957), vol. 5, 194-218.

Visual Evidence

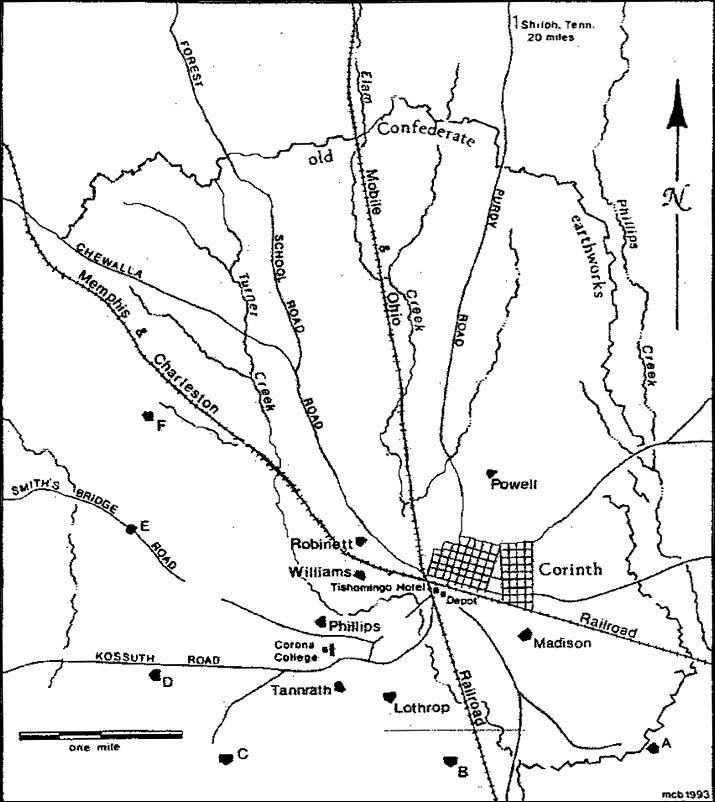

Illustration 1: Fortifications at Corinth, October 1862.

The house-like symbols with names and alphabet letters are Union batteries.

Questions for Illustration 1

1. This map shows fortifications constructed to protect the railroad crossover from attack. Find the jagged line on the north and east representing earthen trenches, constructed principally to protect foot soldiers. The larger symbols represent batteries. Based on the scale, how far from the town are the earthworks? How far are the batteries?

2. Review Readings 1 and 2. Which fortifications were built by the Confederates? Which ones did the Union build? Where do you think each side expected attack to come from?

3. Compare the early fortification with the ones constructed later. How do they differ? What advantages do you think the new ones might have over the old ones? If needed, refer to Readings 1 and 2.

4. Locate the railroads you identified on Map 1. What is the relationship between the fortifications and the railroads? How did their proximity change over time? If needed, refer to Readings 1 and 2.

Visual Evidence

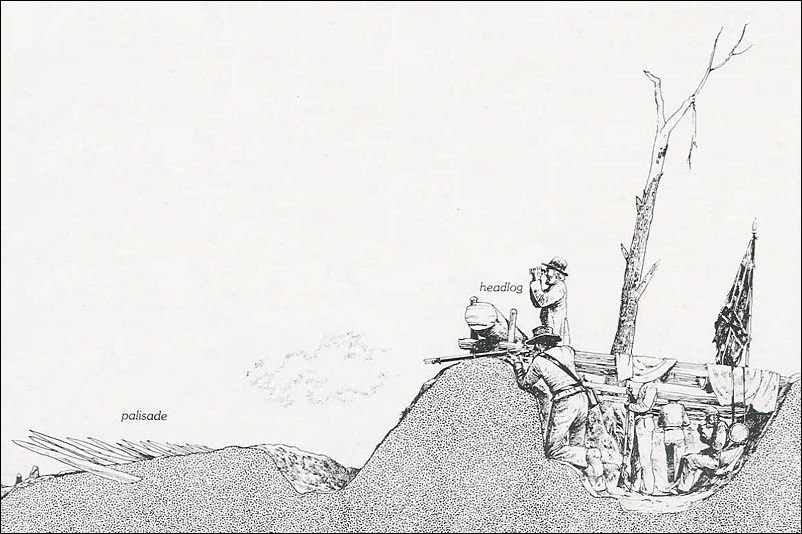

Illustration 2: Typical Field Entrenchment.

(Paddy Griffith, Battle in the Civil War (n.p: Fieldbooks, 1986), 35, Peter Dennis, illustrator. Used by permission)

This illustration shows the simplest and most common type of earthworks, created by soldiers, laborers, or slaves using shovels, picks, or whatever else they could find. The first step would be to pile up dirt for a parapet, or embankment protecting the soldiers. Digging the trench behind it would take longer; the ditch in front was sometimes omitted. The earthworks built by the Union army as they advanced toward Corinth during the Siege and those connecting the large batteries during the Battle of Corinth were of this type.

Questions for Illustration 2

1. Using the men in the trench as a guide, how high do you think the parapet is? How deep is the trench? According to one author, it would take between one and two hours to construct a simple parapet and trench, depending on what kind of dirt it was and whether it was wet or dry. How difficult do you think it would have been to build an earthwork like this?

2. What purpose do you think the headlog served?

3. By the end of the Civil War, armies dug entrenchments every place they stopped. What effect might that have had on the ability of an army to move quickly or to attack by surprise?

Visual Evidence

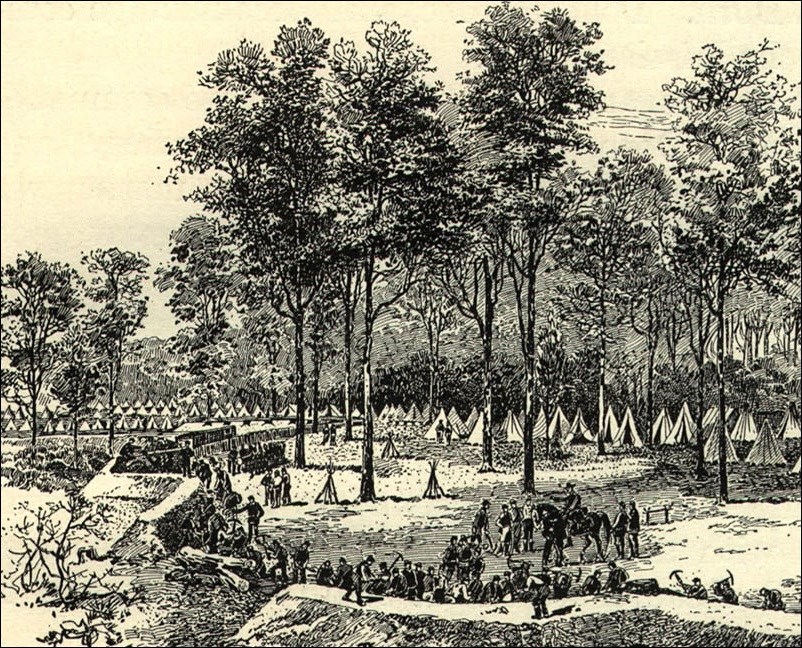

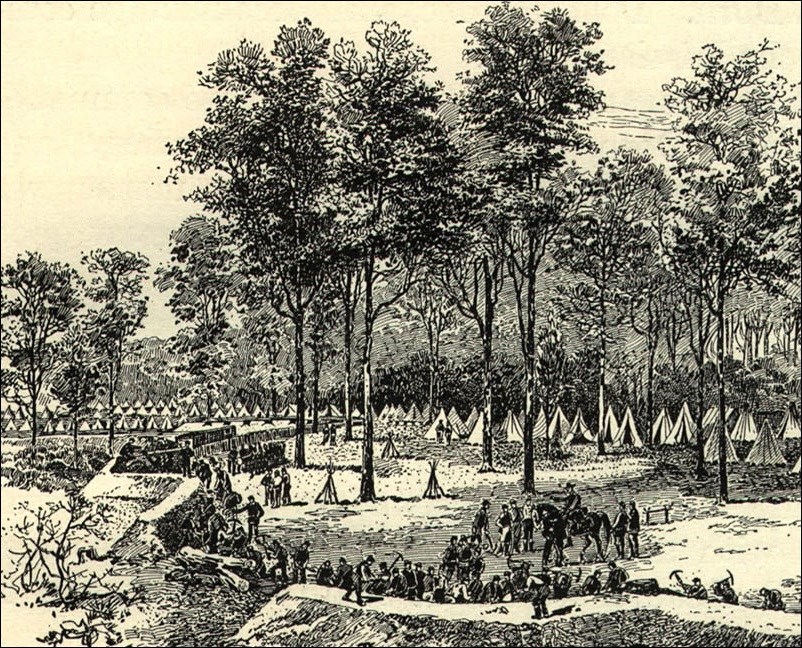

Illustration 3: Union Troops Building Entrenchments on the Road to Corinth, May 1862.

Questions for Illustration 3

1. Examine this sketch closely. It shows the 31st Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry, which was organized in the summer of 1861. A regiment in the Civil War usually consisted of about 400 men. How many men in the illustration are working on the fortifications? What does this tell you about their importance?

2. Notice the logs lying on the ground on the left side of the illustration. Whenever possible, parapets were built around logs, rocks, or large pieces of lumber. Why do you think this would have been done?

3. Notice the zigzag section of the parapet on the left. Based on Reading 3, why do you think it was built that way?

4. Corinth was the 31st Ohio's first major engagement. In his books, Mahan taught that field fortifications were most appropriate for "green," or inexperienced, troops. Why do you think he thought that?

Visual Evidence

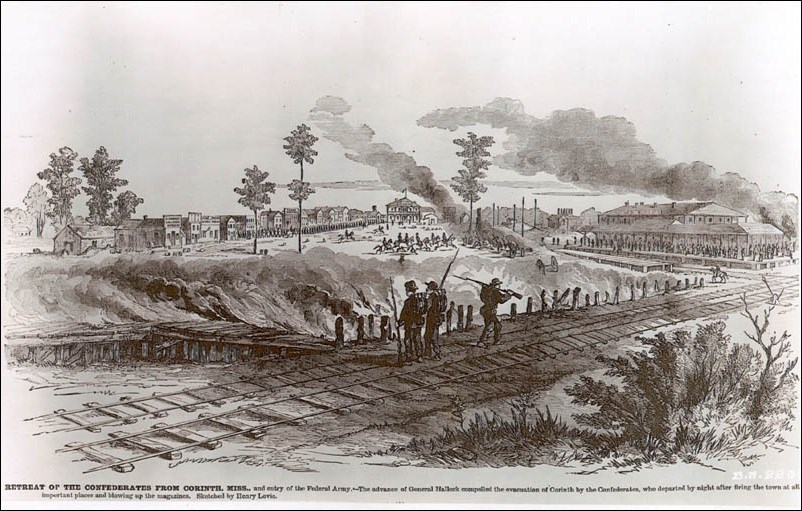

Illustration 4: Corinth after the Confederate Retreat, May 1862.

Questions for Illustration 4

1. According to the caption, this illustration shows the retreat of the Confederate army from Corinth and the entry of Union troops. Examine the illustration closely. Describe the various activities that appear to be taking place. Do you think the image shows what the caption says? Why or why not? How does this compare to what is described in Reading 1?

2. What might have caused all the smoke visible in the illustration?

3. Based on this image and the map shown in Illustration 1, how big a town do you think Corinth was?

4. An estimated 300,000 Union and Confederate soldiers moved through Corinth during the course of the Civil War. What sort of impact do you think these troop movements would have had on the town?

Visual Evidence

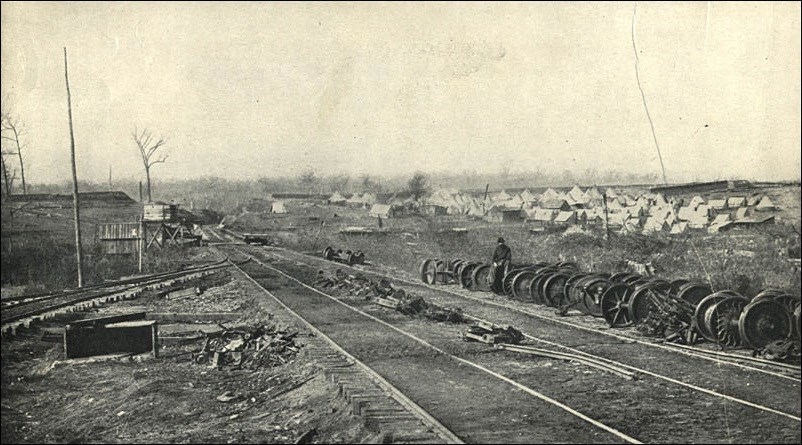

Photo 1: View toward Batteries Robinett and Williams.

Questions for Photo 1

1. This view is looking from the area around the railroad crossover up the tracks of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Locate this view on the map shown in Illustration 1. Can you identify Battery Williams (to the left of the tracks) and Battery Robinett (behind the tent camp on the right) in the photo?

2. What clues can you identify in the photo to suggest why the two batteries were located where they were?

3. The tent camp is located between Battery Robinett and Battery Williams, near the tracks. Why do you think that might be the case?

4. The objects next to the tracks on the right side of the photo appear to be wheels for railroad cars. Why do you think there are so many of them? What might they be used for? How do you think they would have been transported to Corinth?

Visual Evidence

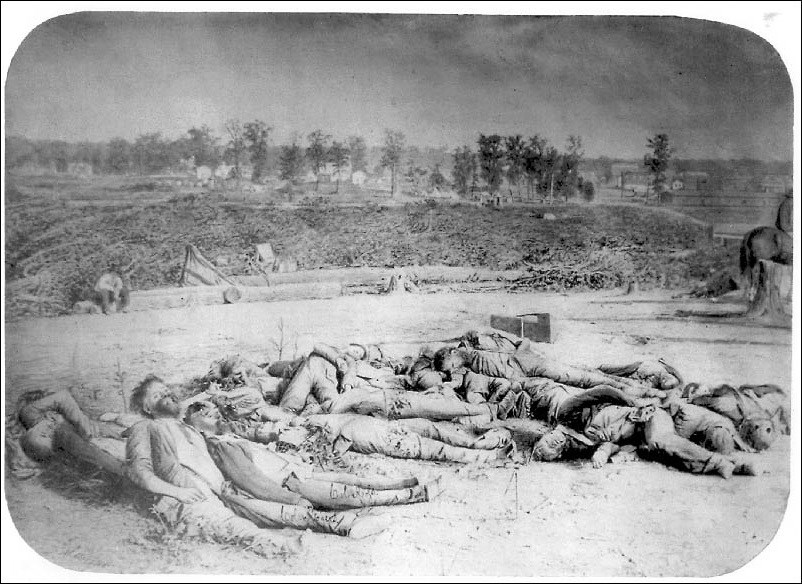

Photo 2: Confederate Dead, Oct. 4, 1862.

Questions for Photo 2

1. Review Reading 3. How did Confederate losses in the Battle of Corinth compare with Union losses? Armies attacking fortified positions usually lost many more men than those defending them. Why do you think that would be the case?

2. This photo shows the Confederates who died attacking Battery Robinett, after their bodies had been collected for burial. If you look carefully, you may be able to see the names that have been scratched on the photographic plate to identify some of the bodies. Who do you think might have done that and why?

3. The Civil War was the first major conflict to be recorded in photographs. Although photographic images had to be converted to lithographs to be printed in newspapers, this was the first time that people not directly involved in the conflict could see unromanticized views of what war was like. Views like this, however, were rarely published. Why do you think that was the case?

Putting It All Together

The growth of the railroads and the introduction of new types of weapons made the Civil War in many ways the first modern war. The following activities will help students apply what they have learned about the effect of these new technologies on warfare. They will also have a chance to investigate how changes in transportation affected the history of their own community.

Activity 1: How to Fight a Battle

American officers entered the Civil War with two conflicting military doctrines. One followed Napoleon, who saw mobility, surprise, and attack as key to victory. The other emphasized control of strategic positions and favored entrenched defenses. For General Halleck, an adherent of the second position, the Union victory at the Siege of Corinth demonstrated the effectiveness of entrenchments and the importance of controlling important transportation centers. He saw the siege as a major victory, gaining an important objective without risking his army in battle.

But the Confederate army escaped intact and the war continued for three more long years. General Grant, committed to a war of mobility, saw the siege as pointless. Many years later, he described it as: "of strategic importance, but . . . barren in every other particular. It was nearly bloodless. It is a question whether the morale of the Confederate troops . . . was not improved by the immunity with which they were permitted to . . . withdraw themselves. On our side I know officers and men . . . were disappointed at the result. They could not see how the mere occupation of places was to close the war while large and effective rebel armies existed."9

Based on what students have learned in this lesson, what advantages do they think each course has? What disadvantages? Which was better military strategy? Ask students to use evidence from the readings to support their argument.

Activity 2: Eyewitness to History

Have students review the readings and write a timeline of the events in the Siege and Battle of Corinth, working either independently or in groups. Then ask students to creatively tell the narrative of the events. Possible formats include digital presentations, graphic novels, or posters. You might review students' project ideas to ensure that they are treating the material with appropiate seriousness. Students should not perform skits based on the material or act out violence in any way.

Activity 3: Transportation in the Local Community

Most cities and towns in the United States were settled because they represented a good place for a water, rail, or road "port," or because they were at some kind of a crossroad. Divide the class into small groups and ask them to research the following questions: What transportation routes have played a role in their community's history? How important are transportation routes today? How do the local routes fit into larger transportation systems--water, rail, airways, or highways? Are these the same systems that were historically important? How have they changed? Are there still places in the community that represent historic transportation patterns? As a class, create a local transportation history display to donate to the local library or historical society, or to display in their school.

9 Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, Vol. l (New York: Charles L. Webster and Co., 1885), 381.

The Siege and Battle of Corinth: A New Kind of War--

Supplementary Resources

When students have completed The Siege and Battle of Corinth: A New Kind of War, they will understand how newly developed technologies affected two military engagements and one tiny town in Mississippi during the Civil War. Students and teachers interested in learning more will find the following resources useful.

Shiloh National Military Park

The Park's website contains useful information which can help students understand the Siege and Battle of Corinth in their wider contexts.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress web page has created a selected Civil War photograph history in their "American Memory" collection. Included on the site is a photographic time line of the Civil War covering major events for each year of the war.

Tags

- civil war

- civil war history

- railroads

- civil war battles

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- military wartime history

- science

- mid 19th century

- mississippi

- mississippi history

- military wartime history

- military and wartime history

- railroad

- transportation

- twhplp

- military history