Last updated: February 26, 2025

Article

Rise and Fall of Foliage

Fall foliage season is a highly anticipated time of year. The fiery explosion of color makes saying goodbye to the long and warm days of summer a bit easier. It also prepares us for the gray drabness of November's “stick season”. Those colors also generate a lot of green for northeastern communities, bringing millions of “leaf peepers”. Leaf peepers generate about $8 billion in New England each year. But climate change threatens to dampen this display and diminish those dollars. Which begs the question: what factors make for a good, or off-par, fall foliage year? It may come as a surprise that forecasting fall foliage season is still a challenging enterprise. Not all variables are 100% understood. But there are several well-known factors: day length, temperature, and precipitation.

NPS / Warren Bielenberg

Timing is Everything

Being in the right place at the right time is everything. And if you like colorful foliage, being in the northeastern U.S. at this time in Earth’s history is the right spot. In geologic time-scales, the region’s northern hardwood forest is still a relatively new phenomenon. After the most recent ice age fully retreated, it took thousands of years for forests to blanket the landscape once again. Hardwood forests of New England have been around more-or-less in their current form for about 10,000 years. That’s only 25 full life-spans of a sugar maple tree which can live for 400 years. Forests are dynamic, ever evolving, and should not be taken for granted. Forests can change in a matter of years, especially with a rapidly warming climate such as ours.

Decreasing day-length and dropping temperatures play key roles and in letting trees "know" it’s time to get ready for winter. Though you wouldn’t know it by looking at them, trees in northern latitudes begin this process as early as late July. In July the day-length shortens by about 30-45 minutes as compared to the June solstice high. Less sun exposure on leaves triggers trees to begin ramping down the photosynthesis engine and to absorb nitrogen back from the leaves. Abundant nitrogen is critical for a tree’s transition into dormancy so it can survive the winter cold. Trees use nitrogen to produce compounds that protect cells from freezing damage, like sugars and proteins. By the end of September, over half of a leaf’s nitrogen has been sent to the tree’s woody tissues.

Next comes the cold. Cool September nights stimulate the cells at the base of each leaf stem to dry out and develop a corky layer between itself and the tree proper. This eventually stops the import of water into the leaf. It also stops the export of carbohydrates that the photosynthesis process created and fed the tree with all summer long. As chlorophyll production grinds to a halt, leaves become less green. What color remains is broken down in sunlight. Green gives way to the underlying pigments previously present, but drowned out by chlorophyll.

Don’t Take Xanthophyll if you’re Allergic

Three main pigments create beautiful fall foliage: xanthophyll, carotene, and anthocyanin. Xanthophyll may sound like one of those prescription drugs you hear about in a TV ads, but it is actually one of the pigments found in tree leaves. Xanthophyll is the same pigment that makes egg yolks yellow. Carotene is the same pigment that makes carrots orange. They also transform the leaves of elms, aspens, maples, and birches to shades of yellow and orange. Tannin pigments contribute to the subdued browns of oaks and help enrich the yellows of beeches.

It takes some additional autumnal alchemy to produce the brilliant reds we get in some foliage seasons. The addition of anthocyanin, specifically. This compound needs sunlight and sugars to be produced, and weather plays a key role in how much is made in a leaf. In early fall, warmish, sunny days maximize photosynthesis, and cool nights minimize the use of accumulated sugars. Cloudy, rainy autumns bring less reds. Autumns that are too cold create hard frosts that rupture plant cells and can cause leaves to drop off early.

Maple is the Staple: Sap, Syrup, Sugar, and Color

There is a big reason why New England foliage, and that of Vermont in particular, are renown world-wide: the sugar maple tree. Only about a hundred-and-fifty years ago, leaf-peeping tourists would have been highly disappointed. Much of the region was cleared of its trees - as high as 80% deforested for Vermont by the 1870’s. But even during those times, more sugar maple trees were spared the axe than other species because they were important sources of maple sugar and syrup production. As farms and fields were abandoned for greener pastures further west, the sugar maples had a clear advantage over other species. Mature trees could produce vast quantities more seeds that other species that were just beginning to re-establish in the area. As a result, there are very likely more sugar maples as a percent of Vermont forests today than there was 400 years ago.

The reason sugar maples can make-or-break a spectacular foliage season is that their leaves contain all three previously mentioned pigments – xanthophyll, carotene, and anthocyanin. During foliage, their leaves run the spectrum of color, with leaves that stay yellow in full shade and turn hues of red in the sun. The proportion of sun to shade, fall weather, and genetics, determines how yellow, orange, or red the leaves get. The more anthocyanin and sugars that get trapped in the leaves, the more brilliant the red color will be if adequate sun is received.

How Might Climate Change Impact Fall Foliage?

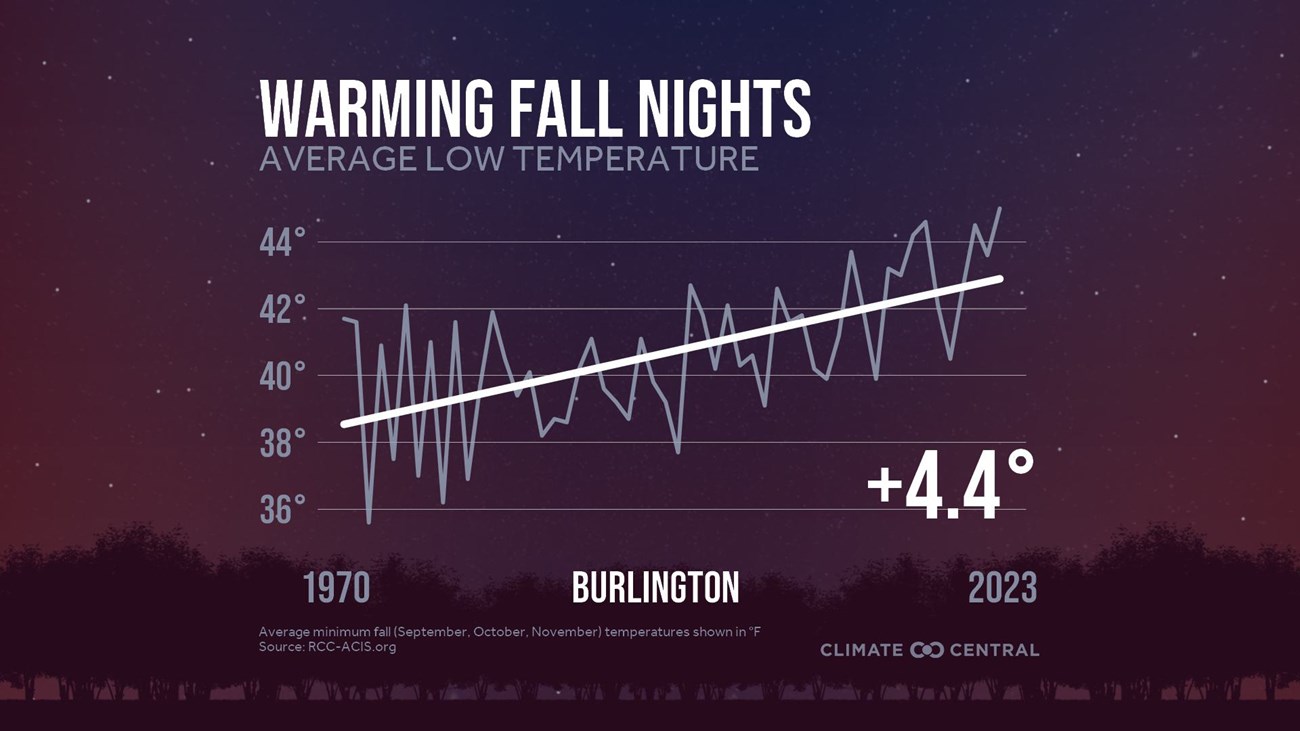

The short answer is that it already is, and it will only continue to even more so over the coming years. The natural conditions that induce fall foliage are shifting with a warming climate. This could have long-reaching impacts on both the ecological and economic value linked to the fall season. Of the three factors that have the biggest impact on the brilliance and breadth of a foliage season: day-length, temperature, and precipitation, only day-length is unaffected by a warming climate. Cool nights are needed to produce the most colorful leaves, and data shows fall nights are warming substantially. A study of 212 U.S. locations found that nights have warmed by an average 2.7°F from 1970 to 2023. Generally, the higher you go in latitude and altitude, the more pronounced the warming is. Burlington Vermont fall nights are almost 4.5°F warmer than they were in 1970.

Ed Sharron photo.

Weather throughout the year can impact what kind of fall foliage season will unfold. Extreme storms can topple trees, or blow leaves off in fall. Prolonged drought and extreme heat stresses trees. Their leaves can shrivel and turn brown before having a chance to produce a colorful display. Conversely, excessive rainfall, especially during the weeks leading up to fall, can also stress trees. This can lead to a reduction in the pigments responsible for vibrant colors. Heavy rains promote the growth of fungi and diseases, which leach away nutrients in the soil. With less soil nutrients, a tree’s overall health and ability to produce colorful leaves decreases.

Native diverse forests can have longer and more brilliant fall colors as the varying species change colors over time. For many native trees the onset of fall marks the end of the growing season, a critical time for forested ecosystems. Warmer fall temperatures can disrupt or delay the temperature cues trees use to start the dormancy process. This can lead to a later, shorter, and often less brilliant peak fall foliage season. Additionally, forest pests and pathogens spread more aggressively in warmer climates and can devastate native tree populations. Invasive species take advantage of warmer falls more readily than most native ones, helping them crowd out native trees. Many invasive plants have earlier leaf emergence and/or later leaf drop than native plants and trees. Several nonnative woody species already extend their autumn growing season by about an extra month when compared with natives. Warming falls are only making it longer. These offenders include the Japanese honeysuckle, buckthorn, and barberry.

No, the spectacular foliage display we’ve enjoyed for generations should not be taken for granted. Actions preventing more severe warming are needed to help ensure future generations will also be able to experience this natural marvel.

Tags

- acadia national park

- appalachian national scenic trail

- marsh - billings - rockefeller national historical park

- minute man national historical park

- saint-gaudens national historical park

- weir farm national historical park

- species spotlight

- netn

- native plants

- climate change

- fall foliage

- sugar maple

- vermont

- invasive species