Last updated: February 27, 2020

Article

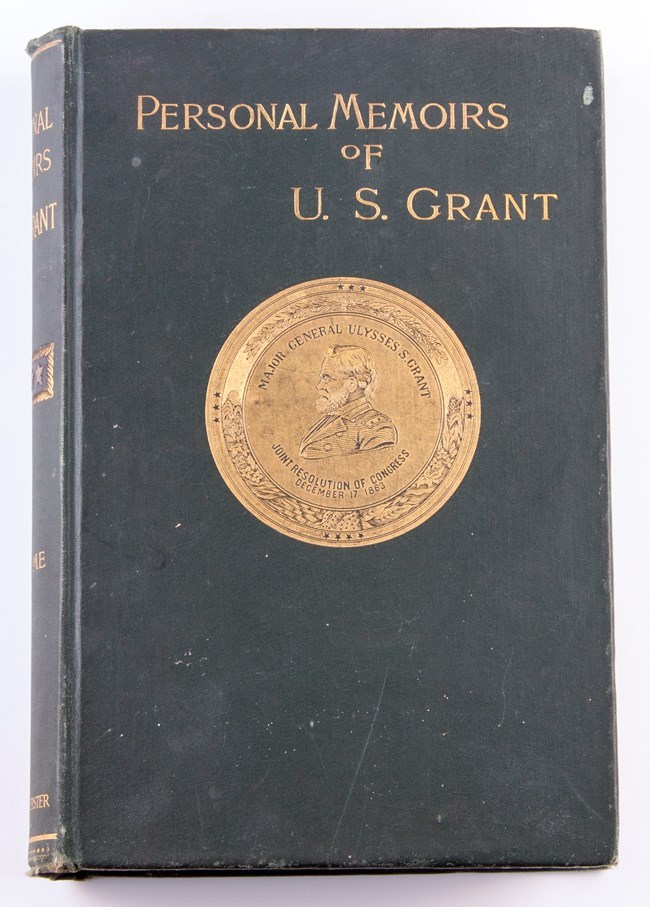

The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant

NPS/David Newmann

A significant event dramatically changed Grant’s mind, however. His son Ulysses, Jr. (nicknamed “Buck”) had entered into a business partnership with Ferdinand Ward, a popular banker and investor who was nicknamed “The Young Napoleon of Finance.” Buck asked his father if he would be interested in joining the partnership. Grant eagerly accepted the offer in early 1884 and the investment firm of Grant and Ward was created. Initially the firm produced great wealth and on paper Grant was a millionaire. It was all a scam, however. Ward had been engaged in a “Ponzi Scheme,” paying out dividends from new investments rather than sales or interest. On May 4th, Ward approached Grant and asked him for a $150,000 cash infusion to keeping the firm afloat after experiencing temporary difficulties with the bank that managed their transactions. Grant approached businessman William Vanderbilt for a loan and gave the loan money to Ward. Two days later Grant discovered that he had lost his entire fortune as the firm collapsed.

Realizing that he needed to find a way to pay back the loan and support his family, Grant turned to writing. He wrote several articles for Century Magazine, but Mark Twain told Grant that he was not being paid enough for his work by The Century Company. Twain convinced Grant to sign a contract with his nephew’s new publishing firm, Charles L. Webster and Company, to write his memoirs. To sweeten the deal, Twain offered Grant a seventy percent royalty from the profits. The need to write the memoirs quickly became more urgent when Grant was diagnosed with inoperable throat cancer that worsened with time.

Grant worked vigorously throughout early 1885 to write the memoirs. He and his wife Julia also relocated in June to a friend's cottage in upstate New York at Mount McGregor to continue writing in a peaceful setting. Grant spent upwards of five to seven hours a day working on the book, aided by his son Frederick and other assistants who checked facts. His servant Harrison Terrell and Doctor John Hancock Douglas also played a crucial role by tending to Grant’s medical needs and provided comfort during moments of great pain. Grant finished the Memoirs three days before his death on July 23, 1885. When The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant were published later that year, they became an instant best-seller. The first paycheck to his widow, Julia Dent Grant, was for $200,000, providing long-term financial stability to the Grant family.

The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant remain in print today and have been regarded as one of the finest written memoirs of a U.S. general or president. As historians John F. Marszaleck, David S. Nolen, and Louie P. Gallo state in their annotated version of the Personal Memoirs, “the Grant Memoirs have continued to intrigue their readers. They have attracted the interest and praise not only of the general reading public, but also of many of the leading literati of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Many have considered the Memoirs to be one of the greatest pieces of nonfiction in American literary history.”