At the start of the war, neither side possessed men of experience or education who truly understood how to design a war plan.

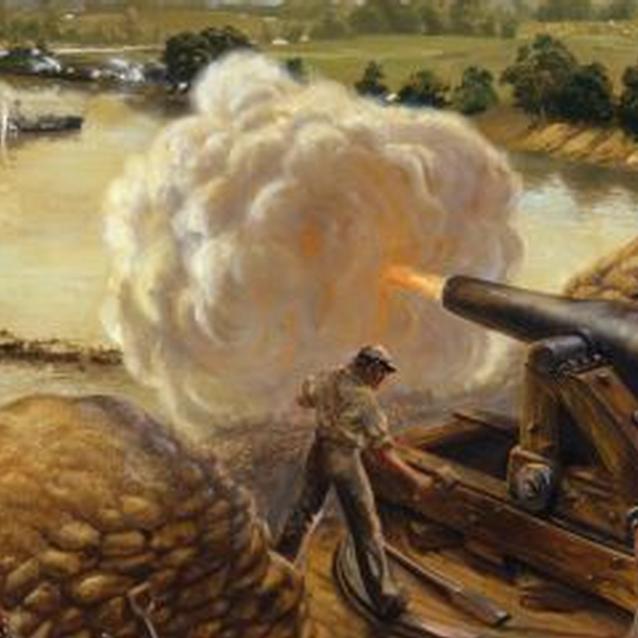

National Park Service, Richmond National Battlefield Park

When the bombardment of Fort Sumter began on April 12, 1861, neither the United States nor the new Confederate States of America foresaw a prolonged war. Each side confidently predicted a short conflict and inevitable victory.

Defining such a victory, for the Confederacy, was straightforward: to secure its independence, it had to keep its primary means of resistance - its armies - in the field, just as George Washington and the Continental Army had done during the Revolutionary War, a lesson seldom lost on Southern leaders. But, to preserve the Union, the United States faced an even larger challenge than that the British had faced. It had to defeat Confederate armies, occupy hostile territory, and suppress the political infrastructure that fomented and supported open rebellion.

Theoretically, at least, the North held insurmountable advantages. It claimed 23 million people and more factories, more food crops, more railroads, and more financial assets than the South. The U.S. Army numbered over 16,000 men, and the U.S. Navy possessed global reach. Abraham Lincoln's recent election confirmed the long-term stability of its political institutions. Jefferson Davis and the nine million residents in the new Confederacy - including four million slaves - could not match that. But numbers alone obscured harsh reality. Most of the U.S. army served in widely scattered western posts, and many naval vessels were stationed overseas or in dry-dock. Few industries could shift quickly from peacetime to wartime production. Thus, when war came, both Lincoln and Davis had to raise and equip mass armies and decide how best to employ them to win a war.

Raising national armies began on the local level, where prominent citizens recruited companies of 100 volunteers aged 18 to 45. The composition of each company typically reflected the tight-knit social network of its home community. With enthusiastic public send-offs - often with flag presentations and Bible readings - the elected officers and their new recruits left home for assignment to a 1000-man state regiment, then mustered into national service. Northerners signed up for as few as three months up to three years and Southerners enlisted for one year. Neither administration, however, was ready to mold these new soldiers into an effective national army. Regiments entered service wearing a colorful array of homemade uniforms, or none at all. Some arrived with modern single-shot, muzzle-loading rifled muskets, while others received obsolescent smoothbores or even modified flintlocks. Cavalrymen had no horses, and new artillery batteries often trained on old Mexican War cannons. With no medical system in place, hundreds died of measles or dysentery before their first campaign.

As the armies organized, generals and political leaders in Washington and Richmond considered the best ways to employ them. Neither side possessed men of experience or education who truly understood how to design a war plan.

Lincoln made clear at the start that he aimed to preserve the Union. To achieve that goal, 75-year-old General Winfield Scott drew upon a preexisting plan to quash a limited domestic insurrection by closing ports and using the presence of armed troops to pressure citizens to demand settlement. Scott's plan, however, had not anticipated the establishment of a new political entity fielding a conventional army, and his simplistic scheme struck many impatient Northerners as weak and time-consuming. Critics rejected the slow squeeze of the so-called "Anaconda Plan" for the quick capture of the Confederate capital at Richmond. In the end, three geographical objectives - the coastal blockade, an armed advance specifically through the Mississippi River valley, and capturing Richmond - guided Union military planning until early 1864.

Jefferson Davis became the primary architect of Confederate military strategy. Determined to remain on the defensive while building his armies, he focused on securing his northern border from invasion. Even though it overstretched his military capabilities, he built a "cordon defense" by posting small armies, of several thousand soldiers each, across northern and western Virginia and southern Kentucky, intending for them to provide mutual support in the event of Union advances.

Ultimately, as these rival strategic visions unfolded, the Appalachian mountains delineated the two major theaters of war east of the Mississippi River. Military operations in the eastern theater centered on the capture or defense of Richmond. In the western theater, armies contested control of the transportation infrastructure, population centers, and agricultural breadbaskets. Smaller forces also contended in the Trans-Mississippi region, and the Navy - with Army cooperation - controlled blockade-related activities along the Confederacy's lengthy coastline.

When active campaigning finally began during the summer of 1861, small clashes erupted from Missouri to Virginia. The first major battle, however, occurred on July 21, when Union troops advancing from Washington toward Richmond collided with Confederate forces near Manassas Junction, Virginia. The battle started well for the Union, but late in the day Southern reinforcements counterattacked and routed them. The battle's 4,900 casualties stunned Northerners and Southerners alike.

First battles teach lessons to both winners and losers. Very quickly, both armies attempted to standardize uniforms to facilitate identification on the battlefield. A new Confederate battle flag was designed to appear less like the Stars and Stripes at a distance. Both armies intensified their training in the fundamentals of accepted battle tactics, especially the workings of the standard two-rank battle line in the open field, bayonet drill, loading muskets "in nine movements," and volley firing.

Lincoln made an especially important change, naming General George B. McClellan to command all Union armies. Ambitious "Little Mac" quickly crafted his own plan for victory, one in which he would personally lead a huge army against major Southern cities from Richmond to New Orleans. He would not move until he built a "perfect" army, however, and he and an impatient Lincoln engaged in a test of wills that the president usually lost.

Thus, military operations reopened in early 1862 in the western theater, far from McClellan's direct involvement. A string of Union victories quickly broke Davis's western defensive cordon. In February, the captures of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson - the latter including 15,000 Confederate prisoners - elevated General Ulysses S. Grant to national prominence. The Confederates surprised Grant near Shiloh Church on the Tennessee River on April 6, but he turned defeat into victory the next day. Simultaneous with Grant's operations, Union naval and ground forces advanced along the Mississippi itself, capturing both Memphis and New Orleans. For his part, Davis never could construct a viable new strategic plan to defend the western theater after his cordon collapsed in the spring of 1862, and Confederate fortunes seemed to be fading quickly. Southern concerns deepened when McClellan finally deployed his army to the tip of a Virginia peninsula very near the site of the recent duel between the ironclad USS Monitor and CSS Virginia and only 70 miles from Richmond. A week's northwestward march, he predicted, would deliver the capital into his hands.

McClellan, however, took six weeks to reach Richmond's outskirts. Thousands died from malaria, diarrhea, and even snakebite in the unhealthy environs of the Virginia swamps. On June 1, General Robert E. Lee took command of Richmond's Confederate defenders and immediately reclaimed the initiative. During the Seven Days Battles from June 26 though July 1, Lee suffered 20,000 casualties in ferocious frontal assaults. McClellan took 4,000 fewer casualties, but he terminated his campaign. With Union progress stalling in the West after Shiloh as well, the bright promise of the Union's spring efforts evaporated.

Now certain of a long war, both Lincoln and Davis reconsidered their manpower needs. In April 1862, Davis extended soldiers' terms of enlistment from one year to "for the war" and reluctantly approved the unpopular practice of conscription to fill Confederate ranks. The Lincoln administration called for 300,000 additional three-year volunteers, but, more controversially, openly discussed the possibility of recruiting African-American soldiers, despite Army regulations forbidding it and strong resistance from the Northern homefront.

During the autumn of 1862, Davis approved a dual east-west offensive onto Northern soil, hoping that battlefield victory might win greater international support. With high hopes, General Braxton Bragg's army advanced into Kentucky and Lee marched into Maryland. The grand design failed, however. Near Sharpsburg, on 17 September, Lee fought McClellan to a standstill near Antietam Creek. The 23,000 casualties both armies suffered in twelve hours still marks the bloodiest day in American military history. In October, Bragg's army suffered a reverse at Perryville, Kentucky. Lincoln, however, did not wait for the western results. After Antietam, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. From now on, the Union's single war aim - preservation of the Union - now expanded to include a second: freeing the slaves.

While the Emancipation Proclamation raised the stakes of the war, it offered no solutions as to how to end it. Unusual winter battles at Fredericksburg, Virginia, and Murfreesboro, Tennessee, produced long casualty lists as 1862 became 1863. Criticism mounted when Lincoln finally signed a Conscription Act in March to fill Northern ranks. At Chancellorsville in Virginia in May and during Grant's spring campaign against Vicksburg in Mississippi, thousands more soldiers died for little long-term advantage.

Two major Union victories - Gettysburg on July 1-3 and Vicksburg's surrender on July 4 - sparked joy in Northern hearts but brought the war no closer to ending. Indeed, a Confederate victory at Chickamauga, Georgia, in September suggested another Southern resurgence. Growing disillusionment, long casualty lists, and homefront sacrifices spawned bread riots in the South, anti-draft riots in the North, and desertions from both armies.

In March 1864, however, Lincoln promoted General Grant - fresh from a November victory at Chattanooga - to command the entire Union Army. The two men completely redesigned the Union war plan. They now rejected geographical targets such as Richmond to focus on destroying the Confederate armies. Relying on superior numbers, Grant planned to order all Union armies to engage enemy forces in their fronts to stop Southern generals from shuttling reinforcements from quiet sectors to make good their losses. Also, because the Confederacy refused to treat the newly recruited United States Colored Troops as prisoners of war, Grant ended prisoner exchanges, a decision that seared Elmira and Andersonville into national memory. Additionally, Grant charged Union armies with destroying all Southern resources - food, industry, transportation - that helped to keep Confederate armies effective.

In May 1864, Grant's coordinated offensive began. General William T. Sherman drove south from Chattanooga against Confederates defending Atlanta. Three separate Union armies targeted Southern forces operating in different parts of Virginia. From early May until late June, Grant's pressure on all Confederate armies stunned veterans accustomed to one- or two-day battles. They now fought, marched, or entrenched daily for weeks on end. Casualty rates soared from bullets, disease, and exhaustion. At the Wilderness (May 5-6), Spotsylvania (May 8-21), the North Anna River (May 23-26), and Cold Harbor (June 1-6), the Army of the Potomac alone lost over 60,000 men, and the press dubbed Grant "the butcher." During Sherman's North Georgia campaign, Southerners frustrated his flanking maneuvers often enough that, at times, as at Kennesaw Mountain in June, the impatient general ordered costly frontal attacks that invariably failed. Defending Confederates suffered fewer losses, but, increasingly, as Grant intended, their casualties could not be replaced.

The experience of combat in 1864 differed from the war's earlier years. Armies seldom traded volleys and charged each other across open fields anymore. Now, earthworks crisscrossed battlefields and required lethal hand-to-hand combat to make or repair breaches in the lines. Artillerymen now used mortars to fire high arcing shots to kill soldiers behind earthworks. By midsummer, the cost of assaulting static defenses brought Sherman to a standstill outside of Atlanta, and Grant laid siege to Petersburg, a key transportation hub south of Richmond, rather than pay the price of charging breastworks.

Summer passed with unceasing and arbitrary death from disease, sharpshooters, and failed assaults, such as that at Petersburg's "Crater" on July 30. Then, in early August, a Union naval flotilla under David Farragut's captured Mobile, leaving only Wilmington open to Southern blockade runners. In September, Sherman captured Atlanta. During the autumn, General Philip Sheridan forced the Confederates from the Shenandoah Valley, destroying harvest-ready crops needed by Southern soldiers and civilians alike. Jefferson Davis could not protect his citizens in the paths of the Union armies, and desertions soared as soldiers left to help their families.

Buoyed by recent victories, Lincoln won reelection in early November, helped in part by the soldier vote. He now encouraged his generals to end the war quickly. A week after the election, Sherman torched Atlanta and launched his controversial "March to the Sea." His 60,000 men had no supply train. Instead, he authorized quartermasters and their work parties to take what the army needed. Terrified Georgians in his path cared little whether Union soldiers at their doors were quartermasters or merely "bummers," and Sherman made Georgia howl.

Sherman advanced into the Carolinas in early 1865 to link up with Grant at Petersburg, where winter quarters broke in early February. Grant and Lee probed for weak points to break the siege, and, at Five Forks on April 1, the overstretched Southern line finally collapsed. Lee withdrew from Petersburg, and Davis ordered Richmond evacuated on April 3. Six days later, Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House. Sherman accepted the surrender of the Confederate forces opposing him near Durham, North Carolina two weeks later.

With these two surrenders, the military operations all but ended. The Union was preserved, but at great cost in blood and treasure. The Civil War cost over 620,000 military deaths from all causes. A new National Cemetery system honored thousands of the fallen, while the war's amputees and veterans wracked with debilitating diseases tried to resume peacetime occupations. Many veterans readjusted to the rhythms of civilian life smoothly, but the trauma of war plagued thousands more for life. Beyond the personal cost, the war brought few immediate changes to military tactics and strategic thought. Postwar military professionals learned those lessons slowly over the next few decades, and, in a new system of schools for the military education of soldiers, found new ways to fight and win wars in the twentieth century.

This essay is taken from The Civil War Remembered, published by the National Park Service and Eastern National. This richly illustrated handbook is available in many national park bookstores or may be purchased online from Eastern at www.eparks.com/store.

National Parks with Relevant Major Resources Related to the Military Experience

All battlefield sites and forts, Andersonville National Historic Site, Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arlington House, Boston National Historical Park, Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area, Civil War Defenses of Washington, C&O Canal National Historical Park, Colonial National Historical Park, Dry Tortugas National Park, Governors Island National Monuent, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, Mammoth Cave National Park, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site, Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site

Tags

- andersonville national historic site

- antietam national battlefield

- appomattox court house national historical park

- chickamauga & chattanooga national military park

- fort donelson national battlefield

- fredericksburg & spotsylvania national military park

- manassas national battlefield park

- petersburg national battlefield

- richmond national battlefield park

- shiloh national military park

- vicksburg national military park

- military

- civil war

Last updated: August 14, 2017