Last updated: July 8, 2024

Article

Great Lakes Mapping

NPS

Look at any map and you’ll find that water is simply flat and blue — no texture, no detail. Even nautical charts, dedicated to the open waters of the world, depict the depth and contours as small black numbers on a plain white or blue background.

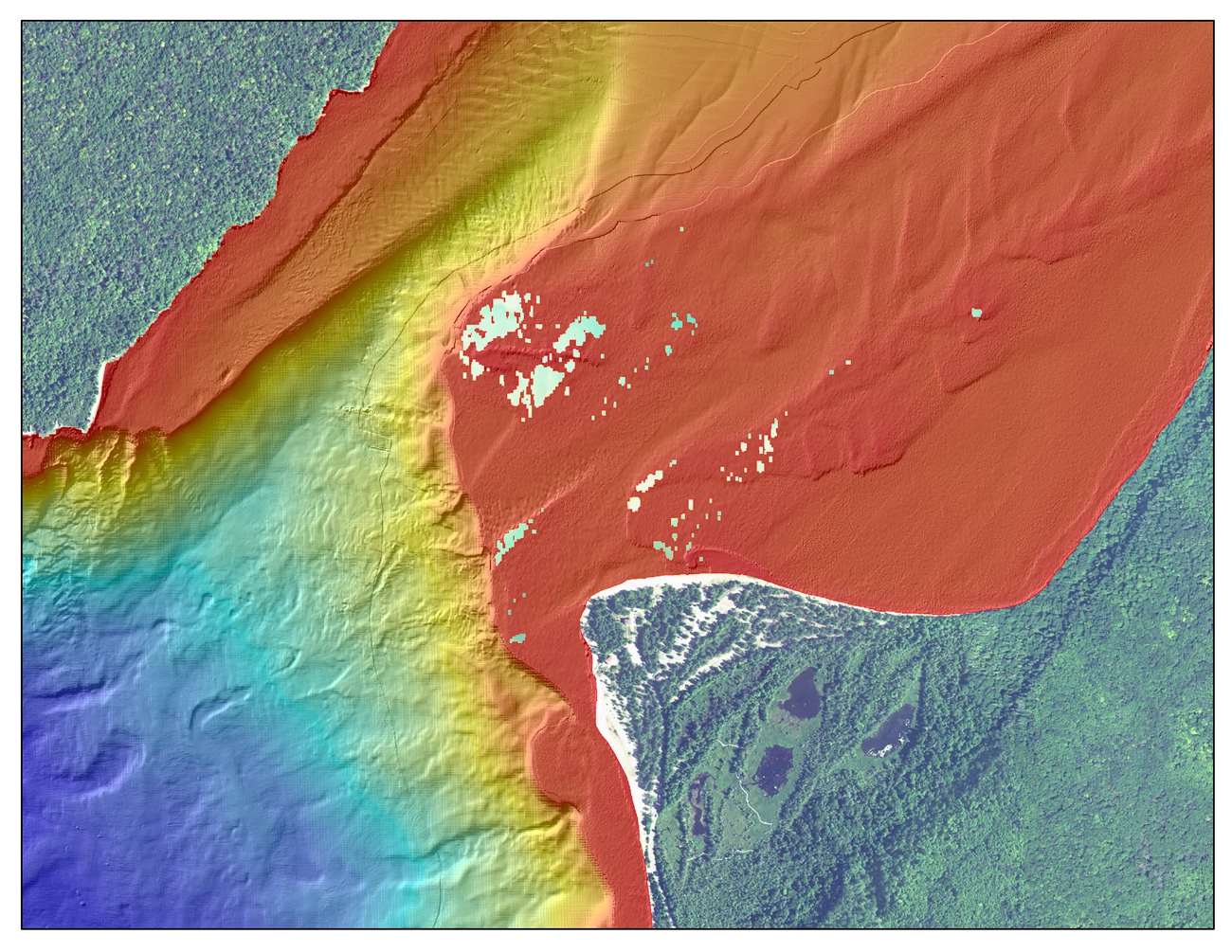

Science and our own individual experiences tell us there is more to lakes than this, and a National Park Service project to map the bottom of Lakes Superior and Michigan has confirmed our suspicions. A lot of sandy lake bottom at Sleeping Bear Dunes? Yep. A lot of rocks below Isle Royale? Of course. But we've also discovered some secrets. Possible submerged glacial features! The story behind the name of Marina Shoal in the Apostle Islands! There is a lot to discover out there beneath the waves.

The Research Vessel Echo (ECho, echo, ...)

The National Park Service Midwest Region's Great Lakes Strategy outlined steps for conserving natural resources in parks along the inland coasts. One of the goals was to “inventory, map, and monitor natural and cultural resources within and near the submerged land boundaries of Great Lakes national parks.” It would be two years before the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) provided much-needed funding for us to begin this work, but since 2010, the NPS has received more than $36 million from the GLRI, with projects having many positive outcomes for parks.

One of the more intensive projects made possible by GLRI funding was the purchase and outfitting of the NPS research vessel Echo, a 28-foot vessel, custom-made to collect multi-beam sonar data in the waters around national parks on Lake Superior. This was just one part of a multi-faceted, multi-year effort to map the lake bottom within park boundaries on Lakes Superior and Michigan. Great Lakes Network staff worked as boat operators, while hydrographic technician Lara Bender ran the sonar and processed the data to create the bathymetric images seen here.

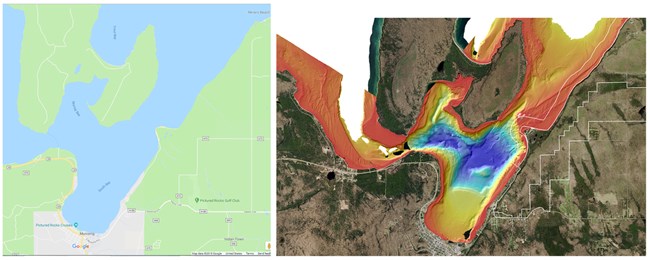

LiDAR (light detection and ranging) data from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers filled in the areas closest to shore and out to a depth of 10 meters (about 30 feet) --- which was sufficient to map all of the park waters at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore on Lake Michigan. Partners at Michigan Technological University and Northwestern Michigan College collected multibeam sonar data at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshores on Lake Michigan.

NPS / L. Bender

Listening is Seeing

Like the topographic maps used by hikers, maps of the lake bottom (called bathymetric maps) show the contours — the shape and depth — of the lake floor. The Echo is equipped with a multi-beam sonar system to collect the information needed to make the maps. This sonar system works in much the same way bats “see” their surroundings. It sends out short bursts of sound that travel through the water to the lake floor, bounce off the bottom, and return to the system that is listening for the echoes. Using the speed of sound in water and the time it takes for the echo to return to the sonar, we can calculate water depth. Taken together, all these echoes paint a high-resolution picture of what lies beneath the surface of the Great Lakes.

NPS (top). NPS / B. Hunter (bottom)

What has all of this time and money brought us? It has contributed new insights to fish habitat, it has provided the foundation for understanding sand movement and restoring areas where nearshore current was altered, and it has drawn our attention to fascinating cultural history, enhancing what we knew and revealing secrets we didn’t know were there.

Fisheries Management

In the Apostle Islands, the Gull Island Shoal is a well-known lake trout spawning area. Mapping the shoal revealed the substrate complexity, which may be a key reason for its value as a lake trout refuge. The sinewy esker-like ridges were an unexpected discovery.

Coastal Restoration Projects

The headquarters of Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore is in an old Coast Guard building on the aptly named Sand Point. A large rock revetment constructed on Sand Point in the 1990s to protect the complex of buildings from erosion caused by wind and waves off of Lake Superior changed the nearshore wave energy, hydrology, and sand movement patterns that had created and maintained the point. As the NPS works to restore the natural flow of energy at Sand Point, the benthic mapping data will be used to evaluate the success of those restoration projects.

NPS

Cultural Resources — Forgotten Stories Revealed

It was winter, and Lara Bender, the technician responsible for operating the Echo's sonar and creating the resulting bathymetric maps, was processing data collected in the spring of 2013 approximately a quarter-mile offshore from Raspberry Island (in the Apostle Islands) when an oval-shaped depression and three curiously symmetrical mounds appeared on the computer screen. What appeared to be a trench underscored the mounds. A screen capture of the image was saved and shown to the park's cultural resources specialist Dave Cooper. Neither Cooper nor anyone else could say for sure what the Echo had found, but many were curious.

Jump ahead to a very windy day in September, and a dive team comprised of Cooper, Midwest Region ecologists (and coordinators of the bathymetric mapping project) Jay Glase and Brenda Moraska Lafrancois, and Great Lakes Network aquatic ecologist David VanderMeulen visited the site. What they found was a very large pile of rocks, some of which they brought to the surface. With a bit of detective work by network staff and Cooper, the mystery began to unfold. The rocks were iron ore. A few days later, Cooper added a large piece to the puzzle. He had pulled out the Raspberry Island lightkeeper's log and found a tantalizing entry. He sent an email to Bender, Glase, and Lafrancois:

My initial research points to the stranding of the steamer Marion on June 18, 1898, loaded with iron ore from Two Harbors, Minnesota. She grounded [off] Raspberry Island and had to dump part of her cargo in order to be towed off. There were other strandings [off] Raspberry, but right now Marion is the only one I know about carrying iron ore.

The lightkeeper also noted that the tug boat Lyon arrived two days after the Marion grounded in order to free her from the shoal. Then a month later, officials from the hydrographic office in Duluth arrived, “trying to locate the cargo that was thrown overboard by the [Steamer] ‘Marina’ and the place she struck.” Cooper noticed how the keeper referred to the ship as the steamer Marina instead of Marion.

The interesting thing to me is this may be the forgotten story of the origins behind the name “Marina Shoal” (still shown on the NOAA charts)––though the vessel was actually named Marion (the name on the bow may have been partly illegible to the keeper’s view).

Bathymetric images by NPS / L. Bender; underwater photo by NPS / B. Lafrancois, iron ore with ruler by NPS / T. Gostomski.

Lake chart showing Marina Shoal and Raspberry Island produced by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Always More to Learn

There is still a lot to be done — and a lot to discover — in the nearshore areas of the Great Lakes parks. This work provides us with a way to show people the Great Lakes and the national parks in particular in ways that few have the chance to see. The future of this project is uncertain, but the tools and expertise are here. What more can we learn about the flat and blue?

NPS

Tags

- apostle islands national lakeshore

- indiana dunes national park

- isle royale national park

- pictured rocks national lakeshore

- sleeping bear dunes national lakeshore

- glkn

- special projects

- great lakes restoration initiative

- bathymetry

- apostle islands national lakeshore

- pictured rocks national lakeshore

- isle royale national park

- sleeping bear dunes national lakeshore

- indiana dunes national lakeshore

- lake superior

- lake michigan

- great lakes network

- geomorphology