Last updated: June 25, 2018

Article

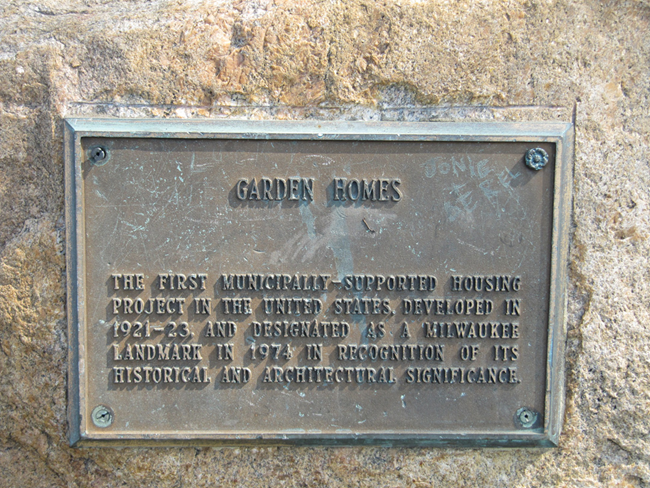

The Garden Homes Community

Photo courtesy of Katherine Kaliszewski, National Park Service.

One cannot talk about Garden Homes without first discussing the Milwaukee Socialist movement. Branch One of the Socialist Democracy of America was in Milwaukee on July 9, 1897, influenced by the city‘s large numbers of people of German descent; by 1910 they were 44.8% of the total population. This was not the Socialist movement that ascribed to the tenets of Karl Marx, but instead looked to reform from the municipal level outwardly. Called 'sewer socialism' by both opponents and followers alike, this was the socialism practiced by Milwaukee‘s leaders. Daniel Hoan officially joined the Socialist Party in 1898, but had spent much of his young life learning socialism‘s values from his father. Hoan‘s devotion to the party followed him through his undergraduate career at the University of Wisconsin and his postgraduate work at Chicago-Kent College of Law.

Hoan returned to Milwaukee and began practicing law in 1908. In 1910, Hoan was elected City Attorney; in the same election Seidel was elected mayor. Six years later, Hoan ran for and won the mayoral seat. One of Hoan‘s major policies was city beautification and planning which he saw as a means to "maximize the use of the city‘s authority to reduce the high cost of living" (The Milwaukee Socialists 1897-1941, 1952, p. 419). In 1918, he renewed the idea for a city planned public housing project by organizing his Housing Commission.

The Housing Commission was a ten-man collective of city employees and Milwaukee businessmen that had two goals. The first was to look at how to alleviate the housing problem in the short term, while the second was to look for long-term solutions for Milwaukee‘s affordable housing shortage. After two years of research, the Commission believed they found their answer in a municipally funded and planned cooperative housing development.

Photo courtesy of Katherine Kaliszewski, National Park Service.

Architect William Schuchardt, a Milwaukee native and Chairman of the Garden Homes Company, planned the neighborhood. Schuchardt had traveled to Europe several times, both after graduation from Cornell University in 1895 and again in 1911. It was during these trips that he encountered the planned, cooperative Garden Cities of Ebenezer Howard, which were also being used in the United States during the City Beautiful movement at this time. Both put an importance on large areas of green space that would be open for anyone in the community to use.

Schuchardt designed nine basic cottages for placement around a central greens pace of the neighborhood and placed them in a fan-like pattern across the development. These nine plans were used for both and single and double unit homes that were built in the community. All of the homes were two-story, box-like structures, with either a front or side-facing gable. All the houses were originally faced with a cream color stucco, over a new building material called flaxolinum keyboard sheathing, which was touted as a superior insulator and would save labor costs. The roofs were covered in red or green asphalt shingles. Modest detailing was used on all the housing in the gable returns, the six-paneled entry doors, the six-over-six double hung windows, and the window shutters.

Each of the homes were built at a cost of about $4,500, and con-struction costs were kept low by using standardized plans and a pro-duction line-like process. But, even with this budget cutting, only ninety-three buildings (a few contained several apartments) were constructed. There was a great interest in the community and for the 105 residences there were over 700 applications. Mayor Hoan later decided that those families that had $1,500 or more in their savings were ineligible for the community and were urged to find housing in the private sector. Many of these applicants were city union leaders and city government employees.

Unfortunately, problems within the community sprang up quickly. The first occupants moved into their home in 1922. Yet, annexation of the area into the Milwaukee city limits was controversial because of earlier Wisconsin annexation laws of the nineteenth century. While final annexation occurred in 1925, complication continued, with the addition of street and sewer improvements that the occupants of Garden Homes were forced to pay for, though they were not included within the price of the house. Residents became disenchanted with the situation after realizing that any money they spent on improvements to their home would be lost unless they stayed for twenty-five years to fulfill ownership. In June of 1925, the state legislature enacted Garden Homes Law Amendment which permitted the sale of the homes for private profit. The Garden Homes Company finally closed in 1933, only after functioning to sell the remaining housing stock and pay off their loans.

Garden Homes was a mix of success and failure. It attracted the attention of both the local laborers and allowed Hoan to be a key figure on the National Committee on Cooperative Housing which made recommendations to Congress in 1922. Yet money issues quickly created conflict in what was supposed to be an affordable housing project. The project did give housing to those who needed it. And it also caught the attention of the Resettlement Administration in the 1930s when they were looking to build one of their Greenbelt towns close to the city. The area is also a lasting testament to the longest serving Socialist mayor in the United States, Daniel Hoan, who was defeated in the 1940 election.

Garden Homes is an important example of the beginning of both Garden Cities and municipally planned public housing. The community is a lasting impression of both the first time Garden City ideas were put to use in the United States, and an example of the longest lasting Socialist administration in the United States. Interest in the community continues to grow. The buildings maintain their original character, though some have added siding and enclosed the porches. But, it has also come under recent attack. In spring 2010, a church within the community that owns one of the buildings filed an intent to demolish their house in order to build a playground. While the action at the moment is blocked, it is still under consideration.

The area was designated a Milwaukee Landmark in 1974 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990.

Originally published in "Exceptional Places" Vol. 5, 2010, a newsletter of the Division of Cultural Resources, Midwest Region. Written by Katherine Kaliszewski.