Union Col. Dixon S. Miles found a war-ravaged wasteland when he took command at Harpers Ferry in the spring of 1862. The Harpers Ferry Armory, which at its peak had produced 10,000 firearms a year, lay in ruins - burned by Confederate forces in 1861. The town's churches and mills had become hospitals; shops and residences had become barracks and stables.

"All seem to think that we will have to surrender or be cut to pieces." Private Newman Eldred, 111th New York

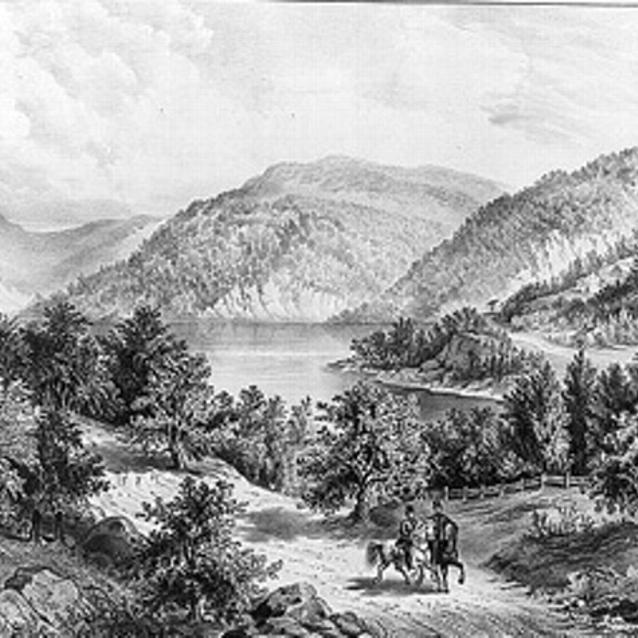

Military Value of Harpers Ferry

Library of Congress

The prewar population of 3,000 had fled. Only 100 local inhabitants dared remain on the border between North and South. One soldier wrote that the blackened ruins of Harpers Ferry presented a "ghost of a former life," and that "the entire place is not actually worth $10."

Even so the military value of Harpers Ferry remained important. It served as a key base of supply for Union operations in the Shenandoah Valley, and protected important Union transportation corridors along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Altogether, in September 1862 Miles commanded 14,000 men at Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg.

One glance at Lee's veterans suggested that his Harpers Ferry mission was impossible. Short on food, destitute of clothing, with many shoeless from hundreds of miles of marching, Lee's ragged army appeared physically incapable of meeting the campaign's tight deadline. Nevertheless, on September 10, Lee bade his detached columns farewell as they left Frederick and pressed on toward Harpers Ferry.

Confederate Command

Library of Congress

Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson divided his command into a three-pronged advance. Commanding the first wing of the advance, Gen. John G. Walker crossed the Potomac River at Noland's Ferry near Point of Rocks, Maryland and advanced across the Northern Virginia countryside to the eastern slope of Loudoun Heights. Colonel Miles had neglected to post any men or artillery on these heights, considering them to be well within the range of Federal gunners on nearby Maryland Heights. Walker, facing no Union opposition, moved a battery of artillery up onto Loudoun Heights by 10 am on September 14, opening fire on the town of Harpers Ferry and the Federal garrison at approximately 1 pm.

Gen. Lafayette McLaws, in commanded the second wing of the Confederate advance, understood the topography around Harpers Ferry well. At 1,448 feet, Maryland Heights was the highest ridge overlooking Harpers Ferry. "So long as Maryland Heights was occupied by the enemy," he wrote, "Harper's Ferry could never be occupied by us. If we gained possession of the heights, the town was no longer tenable to them."

McLaws ordered two infantry brigades to advance south along the crest of Elk Ridge - the northern extension of Maryland Heights. On September 13, these Confederates drove 4,600 Union defenders off the mountain despite "a most obstinate and determined resistance." The next day McLaws opened fire on Harpers Ferry with four guns.

Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson commanded the third Confederate wing himself. Advancing from Frederick to Boonsboro, Maryland, Jackson swept across western Maryland, crossed the Potomac River at Williamsport, captured Martinsburg, and came up behind Harpers Ferry - marching 51 miles in less than two days. Jackson's 14,000-man column occupied School House Ridge, sealing the trap upon the surrounded Federal garrison.

From his command post near Halltown, Jackson methodically and deliberately positioned the cannons of all three wings "to drive the enemy" into extinction. With an elevation of 1400 feet, Maryland Heights dominated the landscape. At sunrise on Sept. 13 the battle to control this strategic summit commenced. "This morning opened with the boom of cannon and the crash of musketry," wrote Sergeant Nicholas DeGraff, 115th New York. Powder smoke laced the dim morning light obscuring any sight of the grey ghosts approaching the Federal position. The untested 126th New York, in the army just 21 days, faced their first field of fire standing firmly beside the veteran 39th New York and 32nd Ohio. "A most obstinate resistance was encountered...our loss was heavy," reported Confederate Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw

The Battle

Library of Congress

Chaos and confusion swept the Union line following the wounding of the 126th New York's Colonel Sherrill. Col. Thomas Ford, Union Commander on Maryland Heights, requested reinforcements, but received none. He continued the fight, but was outnumbered. He reported, "I cannot hold my men . . . I must leave the hill unless you direct otherwise." Following nine hours of fighting the Union troops came off the mountain, handing the Confederates the key to the city. Miles responded, "God Almighty! What does that mean? They are coming down! Hell and Damnation."

Walker's guns positioned on Loudoun Heights fired the first shots on the town, but Confederate guns from Maryland Heights and School House Ridge joined the bombardment. A woman from Harpers Ferry wrote, "The rebel batteries opened up upon us together. The windows rattled; the house shook to its foundations. Heaven and earth seemed collapsing. The roar rolling back to the mountains died amid the deeper roar bursting from their summits."

The intensity of the barrage severely shook the spirit of the green Federal troops. Capt. Samuel C. Armstrong, 125th New York wrote, "I tell you it is dreadful to be a mark for artillery. Bad enough for any, but especially for raw troops; it demoralizes them-it rouses one's courage to be able to fight in return, but to sit still and calmly be cut in two is too much to ask."

On the afternoon of the 14th, in a bold, strategic move, Jackson ordered Gen. A.P. Hill to advance. Using School House Ridge to cover this action, Hill's troops snaked down to the Shenandoah River, flanking the Union left and closing the trap on the Federal garrison. Ten guns were moved across the Shenandoah River to enfilade the Union position.

As evening fell, elements of Hill's Confederate division engaged in a fire fight on the Federal left. On Bolivar Heights at the center of the Union line, Federal skirmishers clashed with Confederates approaching from School House Ridge. "All of a sudden there came a blinding flash in front of our line. We were all alert in a moment and we got in line of battle as quick as possible. We began firing at will," wrote Private Newman Eldred, 111th New York. Louis Hull of the 60th Ohio agreed, writing in his diary on the evening of September 14: "All seem to think that we will have to surrender or be cut to pieces."

Union Surrender

Library of Congress

A thick fog shrouded the Harpers Ferry water gap the morning of September 15, concealing the trap. As the fog lifted a devastating bombardment commenced. The appearance of A.P. Hill's confederate battle line approaching from the Chambers/Murphy Farm made the Union position untenable. "We are as helpless as rats in a cage," wrote Capt. Edward Ripley, 9th Vermont.

The Union commanders at Harpers Ferry held a council of war. Surrounded by a force twice the size of their own and out of long range artillery ammunition, the officers unanimously agreed to surrender. At around 9:00 a.m., white flags were raised by Union troops all along Bolivar Heights. Minutes later, a stray Confederate shell exploded directly behind Miles, mortally wounding the Union commander. Gen. Julius White, second in command, made the final arrangements for the Union surrender.

Jackson captured over 12,500 Union troops at Harpers Ferry - the largest single capture of Federal forces during the entire war. The Confederates also seized 13,000 arms and 47 pieces of artillery.

Although Lee's first advance into the North did not yield the hoped for results for the Confederacy, these few days in September 1862 helped to change the course of the war.

Last updated: August 7, 2017