Last updated: September 17, 2024

Article

The Echo

The Echo Captured

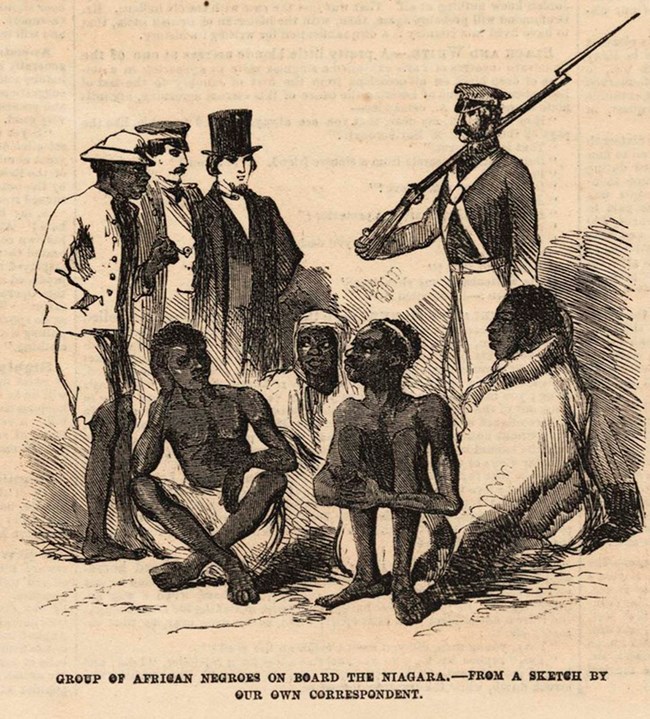

“It is common to speak of a man being reduced to skin and bone” reported one newspaperman, “but one who saw these can scarcely use the expression again.”

On Saturday, August 21, 1858, the USS Dolphin captured the American slave trading ship, Echo, off the coast of Cuba while on patrol. A boarding party discovered more than 300 captives from West Central Africa. Each Echo captive was allotted a space about the size of a coffin. Since the holds were only forty-four inches in height, all but the youngest captives could not stand, except during rare moments when they were allowed on deck during the voyage. One officer described their conditions as “revolting.” In his report, he called them “poor wretches” who looked “half starved, and some of them were mere skeletons.” The Echo had departed the African coast with 450 captives aboard. In total, 137 of the original 450 captives died during the six-week voyage, their bodies dumped overboard. Most died from malnourishment or dysentery.

The captain and crew of the Echo were arrested for violating the ban on the transatlantic slave trade. Congress had passed legislation in 1807, 1818, 1819, and 1820 prohibiting the Atlantic slave trading business. Despite those laws, illicit slave trading continued. The profits were well worth the risk of capture. The American government sent the ship to Charleston, where the crew was put on trial for piracy, a provision of the 1820 law. If convicted, the penalty was death. During the five-day voyage to Charleston, another five captives perished. As American government officials determined the fate of the captives, further lives were lost.

Charleston Museum Illustrated Newspaper Collection

The Echo Captives

Most of the enslaved Africans destined for the Echo were taken from their home communities through sale or kidnapping. According to a reporter in Charleston, over half of the survivors were children and teenagers, and three quarters were male. They spent much of their nearly month long stay at Fort Sumter huddled together on the parade ground. They were in a strange world with a strange language and had no idea what was to become of them. Many of them still suffered from diseases and ailments contracted during the long sea voyage. One doctor assigned to care for them reported, “Their condition on leaving the brig Echo was painful and disgusting in the extreme.” Thirty-five Africans died during twenty-five days of quarantine at Fort Sumter.

The appearance of the Echo, its crew, and human cargo in Charleston created far reaching debate and heated rhetoric both for and against overturning laws banning the slave trade. The Echo affair was used by some to justify deep-rooted convictions that slavery was good “for whites, for the South and even for African slaves.” For them, the trials were a perfect stage to argue for reopening a legal slave trade.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Southern Argument

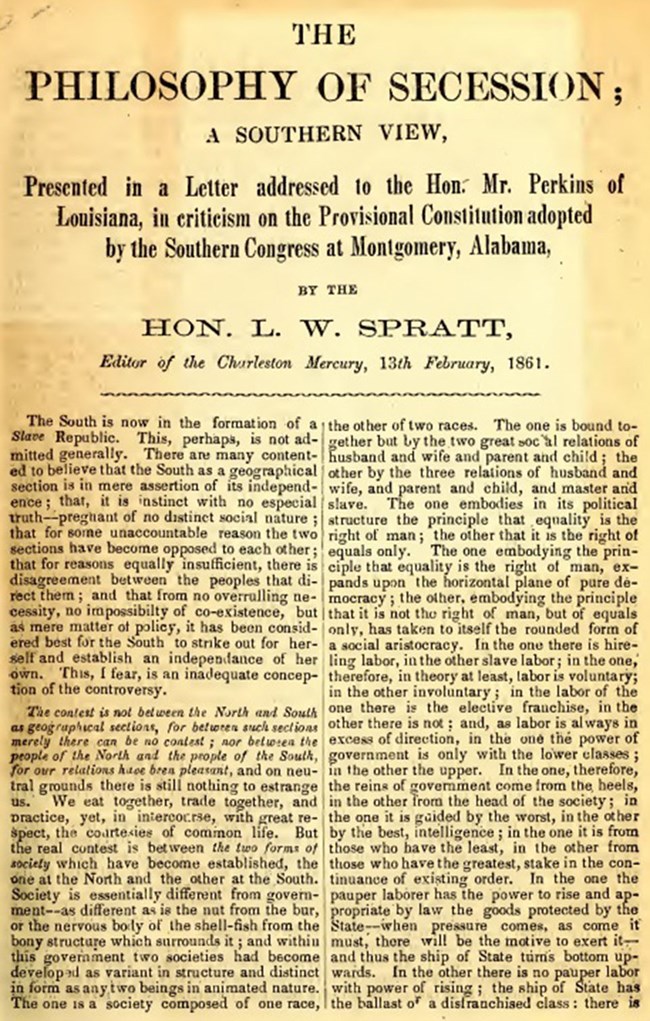

One of the loudest voices belonged to Leonidas Spratt, an influential lawyer and newspaper editor in Charleston. Spratt, who defended the crew in court, maintained that slavery was paramount for the well-being and economic survival of the South, if not for all of humanity. The problem, Spratt wrote about the divide between the north and south is not so much a political or governmental question. “The real contest,” he said, “is between the two forms of society.”

Spratt drew further comparisons between the two societies, equating the morality of slavery with that of a family. In his essay, The Philosophy of Secession: A Southern View, Spratt explained "within this government two societies had become developed as variant in structure and distinct in form as any two beings in animated nature. The one is a society composed of one race, the other of two races. The one is bound together but by the two great social relations of husband and wife and parent and child; the other by the three relations of husband and wife, and parent and child, and master and slave. The one embodies in its political structure the principle that equality is the right of man; the other that it is the right of equals only. The one embodying the principle that equality is the right of man, expands upon the horizontal plane of pure democracy; the other, embodying the principle that it is not the right of man, but of equals only, has taken to itself the rounded form of a social aristocracy."

Arguing that reopening the slave trade would be beneficial to African captives, Spratt insisted that it would rescue them from what he called “heathenism” and the depravity of their own country, that they would become civilized and learn Christianity on southern plantations. He contended that slave labor was more economically efficient than what he referred to as “hireling labor,” meaning impoverished immigrants who were pouring into the US, mainly the north, from Europe.

In addition to the paternalist and racist argument, reopening the trans-Atlantic slave trade would benefit the South politically and economically. An increase in African slaves would mean an increase in population, which would increase representation in Congress. Additionally, reopening the trade would drive down prices for slaves, possibly extending ownership possibilities for poorer whites.

Library of Congress

The Echo Trials and Fate of the Captives

As the Echo’s captives suffered and waited at Fort Sumter, Spratt’s arguments fell largely on deaf ears in the North. Even a Southern paper, the Charleston Courier, called the slave trade “inhuman and brutalizing.” It said, “we would not stain our national flag or our southern name plate by reopening it.” Furthermore, the Courier argued, a renewed legal slave trade would “fill northern pockets with more money since that is where the capital would come from for the trade.”

A US marshal in Charleston, who had been pro-slavery, changed his mind after watching over the captives at Fort Sumter. “I wish that everyone in South Carolina who is in favor of the reopening of the slave trade could have seen what I have been compelled to witness. It seems to me that I can never forget it.”

US District Attorney James Conner, later a supporter of secession and a Confederate general, prosecuted the trial against the crew in federal court in Charleston, South Carolina. Despite the clear guilt of the crew, Spratt turned the focus of his defense of the crew against the constitutionality of the acts restricting the slave trade. Judge Andrew G. Magrath ignored the spirit of the 1820 law when he ruled that the "African slave trade is not piracy." The captain of the Echo, Edward Townsend, was tried separately in federal court in Key West, Florida. The judge presiding over his trial directed the jury to find him not guilty on the technicality that the ship's registry did not confirm Townsend's ownership of the vessel. Within a year, Townsend was back aboard a slaver, bound for Africa, engaged in the illegal trade.

The surviving captives at Fort Sumter were loaded aboard the USS Niagara, bound for Liberia, in September 1858. The U.S. government sponsored this West African republic to re-settle free African Americans and to receive Africans freed from illegal slave ships. The journey to Liberia revealed the limits of liberty for the survivors. Although no longer enslaved, they were still crippled by ill health and bound for a destination not of their choosing. With limited medical attention, they fought influenza, scurvy, and chronic diarrhea. The month-long voyage cost a further seventy-one lives. Upon their arrival in Monrovia, Liberia they were still a few thousand miles from their homelands in Angola. The illegal slave trade was, as one Charlestonian observer put it: “proof in argument of human depravity.”