Popular governments must fashion a strategy of military means and political ends that conform to public opinion.

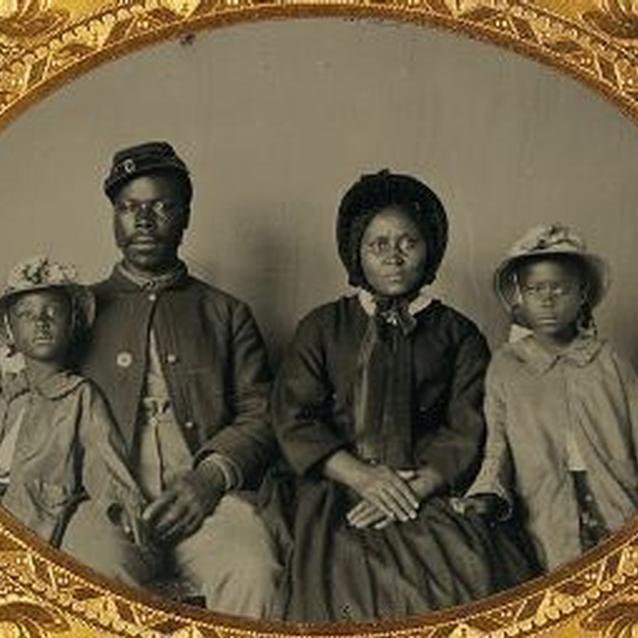

Library of Congress

In the wake of Fort Sumter, before bodies were riddled by bullets, before families were left to mourn fallen fathers and sons, before men returned home maimed and crippled, the American people were captivated by the idea of a quick and glorious conclusion to the Civil War. Only a few voices of pessimism were heard during these heady days of romance and adventure, a realism that bordered on the apocalyptic in which soldiers slaughtered each other with impunity and crazed guerrillas pillaged civilian property without restraint. One dark visionary, a citizen of Massachusetts, predicted that the coming war "would purge our nation of some of its filth and dead heads." Even this man, whose realism was rare, could not have anticipated how a Northern policy devoted to conciliation in 1861 would gradually evolve into a hard war strategy committed to ending slavery, to annihilating Confederate armies, and to destroying the South's capacity to wage war. This transformation in military policy both influenced and reflected the war's radical move away from Union as the North's sole political objective and into a crusade for both emancipation and national reunification. The implementation of hard war by Federal forces during the final two years of the Civil War did not usher in the apocalypse as a few had feared, but it did unleash revolutionary social consequences across the South that reverberated into the modern civil rights era.

The political radicalization of the Civil War was an incredibly complex process that did not come from a simple stroke of the pen or the end of a gun barrel. There was a mighty collision of people, social forces, and institutions at the ground level of war, where armies fought terrible battles, but the results, from a purely military perspective, were surprisingly inconclusive. Nearly every Civil War engagement left both sides bloodied, a little woozy, but almost always standing and eager to get back into the ring and fight. The defeated, whether Union or Confederate, almost always managed to dodge a knock-out blow in their weakened condition. A little rest and recuperation and Civil War armies were ready to continue the seemingly endless rounds of fighting, but the political ramifications of these death matches were unmistakably decisive and verifiable. Battlefield victories or defeats had a tremendous impact on civilian morale, and the voice of the people was critical to the formulation of military policy and war aims. While Confederate grand strategy remained consistently defensive in its orientation throughout the war, early battlefield reverses forced Northern military planners and Abraham Lincoln to embark on a great risk: Could the North fight a war for black liberation and still restore the Union when so many soldiers in the ranks and scores of people back home opposed emancipation? Lincoln had to will the people to fight for this controversial political objective, and his persuasive power rested almost entirely upon the military success of Union armies. It is hardly surprising then that Lincoln declared at his second inaugural that on "the progress of our arms, ...all else chiefly depends."

The progress of Union armies had come to mean something quite different to Lincoln by 1864 when, after enduring a grinding military stalemate, he became convinced that a show of Federal authority could not gently coax white Southerners away from the Confederacy. Destroying the Southerners will to fight and their capacity to wage war was the final solution, but in 1861, before Confederates displayed their tenacious resolve, the military situation seemingly demanded conventional methods of war. Virtually all Americans agreed that grand battles between great armies would decide the war's outcome. From the North's perspective, a war waged exclusively between armies, far removed from Southern civilians and dedicated to protecting slavery, was elemental to a policy of conciliation, a strategy that guided Union armies well into 1862 and was seen as the surest way of restoring national authority without destabilizing the South's social system. General George B. McClellan, noted for his blind faith in conciliation, explained the essence of a strategy dedicated to conquering peace through organized warfare. "Our military success can alone restore the Union," he wrote in 1862. "By thoroughly defeating their armies, taking their strong places, and pursuing a rigidly protective policy as to private property and unarmed personas, and a lenient course as to common soldiers, we may well hope for the permanent restoration of peaceful Union."

Conciliation toward the South dictated McClellan's military decisions as commander-in-chief of Federal forces and as leader of the Army of the Potomac. With hindsight, his conservatism seems either hopelessly naïve or the product of narrow thinking. It was neither. In the first two years of the conflict only a few Northerners would have tolerated a destructive war against the South. Popular governments must fashion a strategy of military means and political ends that conform to public opinion. Democracies embroiled in military conflict, no matter how professional their armies may be, demand a voice in the ways of war. If McClellan had unleashed a strategy of exhaustion and attrition, the Northern people would have taken to the streets, especially since the press was virtually unified in telling its readers to expect modest casualties, little physical destruction, and a quick capture of Richmond, Virginia.

Hopes for a speedy and final victory through easy fighting evaporated with the Seven Days battles fought outside Richmond from June 25 to July 1, 1862, when McClellan's Army of the Potomac, poised to capture the capital of the Confederacy, was driven away by a bloody offensive under Robert E. Lee. Southern success on the battlefield darkened the mood of the North, convincing many at home and in the Federal army that harsher measures must descend on the Confederacy. The resilience of the Southern people, the determination of the common Confederate soldier, and the skill of Confederate generalship had caught Lincoln and other Northerners off guard. The mere presence of Union troops, as they had expected, did not demoralize the enemy. It had united most white Southerners to fight for independence. The policy of conciliation was doomed.

Almost two weeks after the Seven Days battles ended, Lincoln revealed that he had changed his mind about emancipation---forever fixing Union military strategy on a trajectory toward hard war. He explained to members of his cabinet that destroying slavery "was a military necessity absolutely essential for the salvation of the Union, that we must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued." The Northern populace did not rejoice at the prospect of emancipation during the summer of 1862, but grim news from the front, including sensationalized reports of Confederates desecrating the Union dead, drinking from their skulls, and allowing corpses to rot in the sun hardened hearts, radicalized political sentiments. Meanwhile, green Union soldiers were quickly turning into tough veterans, weary of the never-ending hard labor at the front while thousands of slaves who could be utilized by Federal armies were allowed to toil in the fields of their masters or dig entrenchments for the Confederacy. No one could ignore this issue because the slaves themselves did not go limp when Union troops entered their neighborhoods. Scores of blacks fled their masters, turning Northern armies into forces of liberation, not just agents for reunion. But many of these runaways were returned to their owners since the Federal government did not allow the military to free slaves until Congress passed the Confiscation Act of July 1862, allowing Union armies to keep the property of Confederates, including slaves. In the interim it did not take long for even the dullest of Union soldiers to recognize that every runaway escorted back to Confederate lines freed up a Southern white man to kill Union Soldiers on the battlefield. There were, however, serious reservations about the military necessity argument for emancipation, as many officers feared that throngs of freed African Americans would engulf Union armies, depleting resources, inhibiting mobility, and unleashing a wave of slave uprisings across the Southern countryside.

Against the advice of senior military leadership, Lincoln went public with the Emancipation Proclamation as a declared war aim after the battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, a monumental act that gave official sanction to the revolutionary forces that had been brewing on the ground since First Manassas. From the moment that Federal soldiers touched enemy soil, they had been turning up the heat against Southern civilians, ignoring War Department dictates about protecting private property, as they faced pragmatic challenges of surviving in hostile country. The taking of a farmer's fence rail or the appropriation of a "secesh" pig was a spontaneous act that was routinely but not consistently punished by senior officers. Soon, however, logistical problems besieged Northern armies, forcing commanders to look the other way when the rank-and-file stole from Southern civilians. As vigorous foraging became customary in the ranks, soldiers did not accept the practice without considering the military impact of destroying Confederate property. While many expressed misgivings about the ethics of such a policy, most Union soldiers came to accept destructive war as the only way to subdue the South. After Union soldiers went on a rampage in Fredericksburg on December 11, 1862, an Indiana officer named David Beem, who initially bemoaned the sacking of the Virginia city as a wanton act of violence, changed his opinion within days, writing that "no person is more opposed to war than I am; but when it becomes a necessity and is forced upon us by the enemies of Freedom, then I am in for war, and as a means of putting down rebellion." "I sanction everything that helps to effect it," he added, "I would burn and destroy every city in the South, and emancipate every slave, if by doing so our cherished institutions could be preserved and handed to future generations."

Few soldiers were as eloquent as Beem in elevating the rhetoric of hard war to high idealism. In fact, many at home and in the army condemned the marriage of Union and emancipation on the altar of hard war as an uncivilized act in God's eyes. Their fury against the Lincoln administration boiled over with the imposition of the draft on March 3, 1863, when vast numbers of Northerners, especially those from the Midwest and urban areas, violently demonstrated against the war. Endless casualties, racial hostility, economic hardship, and anger over conscription unleashed four days of unrestrained violence in New York City from July 13-16, 1863. Mostly Irish workers went on a destructive rampage in Manhattan, brought to a bloody end when veterans of the Army of the Potomac arrived on the scene. They dispersed the protesters with a few well-aimed volleys, but not before millions of dollars of property had been destroyed.

With every Union defeat on the battlefield, there was a surge in antiwar activity on the Northern home front, reaching its apogee during the summer of 1864 when Federal offensives had stalled in Virginia and Georgia. Only Northern victories in the Shenandoah Valley (Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864) the fall of Mobile (August 5, 1864), and, most importantly, the capture of Atlanta (September 1, 1864) stabilized Northern morale, discrediting the war's most outspoken critics while getting the populace to believe that final victory was near. Those crucial Union triumphs paved the way for Lincoln's re-election, a campaign that rested on a platform calling for the unconditional surrender of the Confederacy and a 13th Amendment to abolish slavery everywhere.

The North's hard war strategy produced a wide range of complex and contradictory reactions among Confederates, inspiring some to bitterly resist a foe that they considered barbaric while others were at odds with themselves, hating the enemy for its depredations but also hating the death and destruction wrought by the conflict. Others turned despondent, giving up on the Confederacy since it could not sufficiently protect its people from the bruising advances of Union forces. Whether they remained true believers in the Confederacy or dissenters against the cause, every white Southerner knew that with the Emancipation Proclamation defeat meant reckoning with a world without slavery. The war had become a life and death struggle for Confederates of all social classes. They especially detested Lincoln's employment of black soldiers, seeing this measure as the equivalent to fomenting a slave rebellion. Confederates of this mindset refused to show quarter to United States Colored Troops. One of the most notorious incidents occurred on July 30, 1864, at the battle of the Crater, during the siege of Petersburg, where Southern troops shot down hundreds of black soldiers after they had tried to surrender (It should be noted that some white soldiers also murdered their black comrades at the Crater, for fear of being captured alongside a black man). Few Confederates expressed remorse for this atrocity, believing that such murderous behavior was a defensible act of survival. For in revolutions prisoners are rarely taken, an extreme stance that the Richmond Enquirer endorsed after the Crater when it encouraged Southern officers to "let the work, which God has entrusted to you and your brave men, go forward to its full completion that is, until every negro has been slaughtered."

A powerful and fanatical spirit of revenge infused both sides, obscuring the degree of restraint shown by the North in its hard war against the South. Memories of the Civil War have further distorted the perception of Union soldiers as the second coming of the Vandal hordes. In actuality generals like Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman never imagined or pursued an all-annihilating concept of total war. The intent was not to physically hurt Southern civilians, but to detach them from their loyalty to the Confederacy, even if that meant squelching their will to fight by making them feel terror, grief, and hunger. Southern slaveholders (especially those who were avowed secessionists), surplus crops and livestock, and factories were the designated targets, not all the Southern people. The excesses of severity, moreover, were generally harnessed by officers (except in South Carolina) who implemented their orders with care and discrimination. Union soldiers were hardly saints, but they were not the merciless thugs condemned by heritage groups today.

Early war experiences had taught Grant that battlefield victories were usually indecisive and that occupying Southern territory almost always created unsolvable logistical issues. He also knew that a war of attrition was too costly, both in human and political terms. Grant gradually came to embrace a raiding strategy as a key component of the overall hard war policy, a strategy aimed primarily at Southern railroads, communications, and military resources. It worked masterfully, as Union operations in 1864, most famously Sherman's "March to the Sea" destroyed the South's capacity to make war while crushing the people's will to resist. By early winter of 1865, Confederate morale was nearing collapse, soldiers were deserting in droves, and civilians were clamoring for peace. Lee predicted from the Petersburg trenches on March 9, 1865, that "unless the men and animals can be subsisted, the army cannot be kept together." His bleak assessment was the plight of all Confederate armies, and the consequence of a Union strategy that had exhausted resources across the South.

Americans who had predicted in 1861 that the war would ultimately be decided by a great clash of opposing armies were wildly wrong, since the exhaustion of the South's logistical base and the liquidation of its slave labor force occurred not through a decisive engagement but by controlled pillaging and planned destruction. The "terrible swift sword" of Union armies, while exacting a horrible human cost on the battlefield, was leveled against the South with a mixture of severity and restraint, a unique consequence of a democracy at war in which Union soldiers, who were called "thinking bayonets" by Lincoln, pursued revolutionary acts in the field with admirable political and moral moderation.

This essay is taken from The Civil War Remembered, published by the National Park Service and Eastern National. This richly illustrated handbook is available in many national park bookstores or may be purchased online from Eastern at www.eparks.com/store.

Parks with Relevant Major Resources Related to the Changing War

All battlefield sites and forts, Andersonville National Historic Site, Cane River Creole National Historical Park, Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, Hampton National Historic Site, Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, Natchez National Historic Site, Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site, Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site

Tags

- andersonville national historic site

- antietam national battlefield

- brices cross roads national battlefield site

- cane river creole national historical park

- charles pinckney national historic site

- fort davis national historic site

- fort donelson national battlefield

- fort dupont park

- fort foote park

- fort mchenry national monument and historic shrine

- fort monroe national monument

- fort pulaski national monument

- fort scott national historic site

- fort smith national historic site

- fort sumter and fort moultrie national historical park

- fort union national monument

- fort vancouver national historic site

- fort washington park

- fredericksburg & spotsylvania national military park

- gettysburg national military park

- harpers ferry national historical park

- hampton national historic site

- lincoln home national historic site

- marsh - billings - rockefeller national historical park

- monocacy national battlefield

- natchez national historical park

- palo alto battlefield national historical park

- pecos national historical park

- petersburg national battlefield

- richmond national battlefield park

- shiloh national military park

- stones river national battlefield

- tuskegee institute national historic site

- tupelo national battlefield

- ulysses s grant national historic site

- vicksburg national military park

- military

Last updated: February 4, 2015