Last updated: September 19, 2023

Article

The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific (Teaching with Historic Places)

For centuries, thousands of albatrosses have lived on the desolate islands that comprise the Midway Atoll. Beautiful in flight, but ungainly in their movement on land, the albatrosses were called "gooney birds" by the men stationed on the islands during World War II. The birds soiled the runways, clogged the engines of departing aircraft, and were always, always underfoot. Today, the shadows of their huge wings still dapple the glassy sea as they glide towards the islands to nest. They still perch on the airport runways and the old ammunition magazines and gun batteries, but they no longer need to do daily battle with America's armed forces for possession of the islands.

Inhabited by humans for less than a century, Midway dominated world news for a brief time in the early summer of 1942. These tiny islands were the focus of a brutal struggle between the Japanese Imperial Navy and the United States Pacific Fleet. The U.S. victory here ended Japan's seemingly unstoppable advance across the Pacific and began a U.S. offensive that would end three years later at the doorstep of the Home Islands.

About This Lesson

This lesson plan is based on the National Historic Landmark nomination file, "World War II Facilities at Midway" (with photographs), and historic accounts of the campaign. Kathleen Hunter, an educational consultant, wrote The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific. Marilyn Harper, Fay Metcalf, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff edited the lesson. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson can be used in American history, social studies, and geography courses in units on World War II.

Time period: Mid 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

-

Standard 3A- The student understands the international background of World War II.

-

Standard 3B- The student understands World War II and how the allies prevailed.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

-

Standard C - The student uses appropriate resources, data sources, and geographic tools such as aerial photographs, satellite images, geographic information systems (GIS), map projections, and cartography to generate, manipulate, and interprets information such as atlases, data bases, grid systems, charts, graphs, and maps.

-

Standard E - The student locates and describes varying land forms and geographic features, such as mountains, plateaus, islands, rain forests, deserts, and oceans, and explain their relationships within the ecosystem.

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard G - The student identifies and interprets examples of stereotyping, conformity, and altruism.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard B - The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

-

Standard C - The student describes the various forms institutions take and the interactions of people with institutions.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard D - The student describes the way nations and organizations respond to forces of unity and diversity affecting order and security.

-

Standard G - The student describes and analyzes the role of technology in communications, transportation, information-processing, weapons development, and other areas as it contributes to or helps resolves issues.

-

Standard I - The student gives examples and how governemnts attempt to acheive their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology and Society

-

Standard A - The student examines and describes the influence of culture on scientific and technological choices and advancement, such as in transportation, medicine, and warfare.

-

Standard E - The student seeks reasonable and ethical solutions to problems that arise when scientific advancements and social norms or values come into conflict.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard C - The student describes and analyze the effects of changing technologies on the global community.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard B - The student identifies and interprets sources and examples of the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

-

Standard C - The student locate, access, analyze, organize, and apply information about selected public issues recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard D - The student practice forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

-

Standard E - The student explain and analyze various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explain the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard G - The student analyze the influence of diverse forms of public opinion on the development of public policy and decision-making.

Objectives for students

1) To determine why Midway became strategically important during World War II.

2) To describe the course of the Battle of Midway.

3) To analyze accounts of participants in the battle.

4) To examine how changing technology affects the conduct of warfare.

5) To research war memorials in the local community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps showing Japanese conquests in the South Pacific and the Midway Atoll;

2) three readings on the Midway Atoll and the Battle of Midway;

3) six photos of the atoll and the battle.

Visiting the site

The World War II facilities on Midway are now part of the Battle of Midway National Memorial. The Memorial is located in the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. For more information, contact the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, P.O. Box 29460, Station #4, Honolulu, Hawaii, 96820-1860, or visit the refuge's web site.

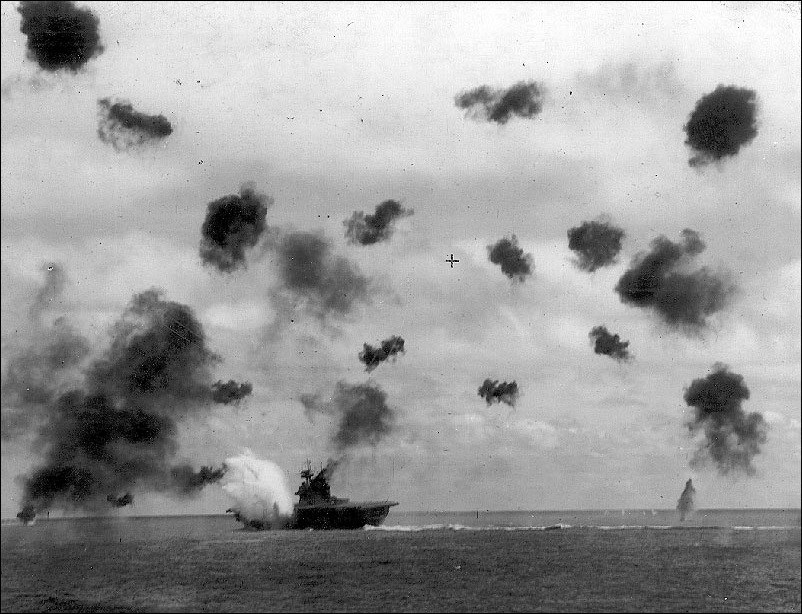

What do you think caused the damage shown in this photograph?

Setting the Stage

In the early 20th century, Japan resolved to take its place among the world's great powers. The needs of its booming population, its lack of natural resources, and the growing power of its military led the nation on a search for more territory. Between 1905 and the late 1930s, it occupied Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, and parts of China; withdrew from the League of Nations; and defied international naval arms restrictions. As Hitler and Mussolini set out to dominate Europe, Japan sought the same type of influence in the Pacific. In 1940, Japan signed the Tripartite Pact. The main purpose of the Tripartite Pack was to keep the United States out of the war by threatening a two-front war in the Atlantic and the Pacific. Germany, Italy, and Japan also divided Europe and Greater East Asia among themselves. German occupation of France and the Netherlands left the Southeast Asian colonies of those countries unprotected and vulnerable to Japanese invasion.

The United States and Britain applied harsh economic sanctions, hoping to slow Japanese expansion into the former colonial areas. In July 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt froze all Japanese assets in the U. S., shutting off vitally needed oil supplies. Even as negotiations were going on between the two governments, Japan continued its aggression in China, Indochina, and other Southeast Asian territories. Then, on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked U.S. ships and aircraft at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. By December 8, the United States and Japan were at war.

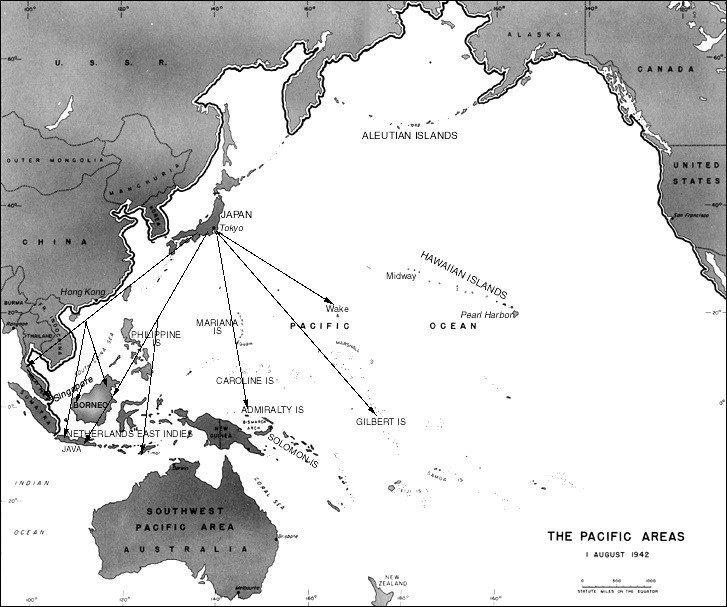

South Asia, with its supplies of oil, tin, rubber, and quinine, was the first priority in Japanese plans for the war. The arrows on this map show Japan's apparently unstoppable advance during the months following Pearl Harbor. By early May, the Japanese controlled Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines, the American islands of Wake and Guam, and much of south Asia.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate Hawaii, Japan, China, and the clusters of islands between Hawaii and Japan. The headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet were in Hawaii. Why do you think Americans were so shocked by the attack on Pearl Harbor?

2. Find Midway Atoll, located northwest of Honolulu about 3000 nautical miles from the west coast of the United States and 2250 from Tokyo, Japan. How do you think these tiny Pacific islands might have been useful to whatever country that controlled them during World War II?

3. Midway, the westernmost of the Hawaiian island chain, was sometimes called the "sentry to Hawaii." Why would the United States think it was essential to control the atoll?

4. Study the map carefully. How long did it take Japan to take control of these areas? Admiral Yamamoto, Commander of the Japanese Pacific Fleet, reportedly was concerned about the effect of "victory disease" on his forces? What do you think he meant by that?

Questions for Map 2

1. An atoll is a ring of coral built up on the top of the crater of a submerged volcano to form a lagoon. How many islands are there inside the lagoon at Midway?

2. How large are Sand and Eastern Islands?

3. The islands are nearly flat and have very little natural vegetation. In spite of being surrounded by water, there is no fresh water. How much work do you think would be needed to construct and maintain a military base here?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Out of Obscurity

After the first recorded landing on the atoll in 1859, Midway became a United States possession in 1867. A trans-Pacific cable station was established there in 1903. In 1935, Pan American Airways used Sand Island as a stopover on its new seaplane route between the U.S. and Asia. A 1938-39 study of U.S. defense needs recommended Midway as a base for Navy patrol planes and submarines. Soon thereafter, construction began on a seaplane hangar and other facilities on Sand Island and an airfield on the smaller Eastern Island.

Midway occupied an important place in Japanese military planning. According to plans made before Pearl Harbor, the Japanese fleet would attack and occupy Midway and the Aleutian Islands in Alaska as soon as their position in South Asia was stabilized. Two Japanese destroyers bombarded the Navy base on Midway on December 7, 1941, damaging buildings and destroying one patrol plane. In the spring of 1942, flush with victory after victory in the Pacific and southeast Asia, Japan prepared to establish a toehold in the Aleutians; to occupy Midway and convert it into an air base and jumping off point for an invasion of Hawaii; and to lure what was left of the U.S. Pacific Fleet into the Midway area for a decisive battle that would finish it off.

The Americans had their own plans for the little atoll. With the fall of Wake Island to the Japanese in late December 1941, Midway became the westernmost U.S. outpost in the central Pacific. Defenses on the atoll were strengthened between December and April. Land-based bombers and fighters were stationed on Eastern Island. U.S. Marines provided defensive artillery and infantry. Operating from the atoll's lagoon, seaplanes patrolled toward the Japanese-held Marshall Islands and Wake, checking on enemy activities and guarding against further attacks on Hawaii. There were occasional clashes when planes from Midway and those from the Japanese islands met over the Pacific.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, inspected Midway in early May 1942, conferring with the local commanders, Navy Capt. Cyril T. Simard and Marine Col. Harold D. Shannon. Based on reports coming from U.S. intelligence, Nimitz believed the Japanese were planning an attack on Midway. The Japanese Combined Fleet depended on a complex system of codes to communicate by radio. The codes were regularly modified to avoid detection, but in the confusion of the rapid Japanese expansion in the South Pacific the change scheduled for early 1942 was delayed. In Washington, DC, and Hawaii, codebreakers worked around-the-clock to interpret every detail of the complex secret messages. By the spring, they were having some success--picking up words and phrases that gave them clues to Japan's naval strategies. One communication from the Japanese navy suggested they needed supplies for a powerful long distance strike. Were they planning to hit Hawaii again? The west coast of the United States? Midway? The abbreviation "AF" appeared frequently in radio communications. Navy intelligence in Hawaii concluded that Midway was the target and they convinced Admiral Nimitz.

Top Naval officers in Washington were not so sure. They could not believe that the Japanese would send a huge fleet to take a little atoll. It would be like fishing for minnows with a harpoon.¹ Lt. Comm. Jasper Homes came up with a brilliant idea. Knowing that Midway depended on desalinated water, he used the old undersea cable to send a message to the military there. He asked them to send out an uncoded radio message stating that the purification system had broken down: "We have only enough water for two weeks. Please supply us immediately."² A few days later, the code breakers picked up a Japanese message saying that AF had water problems. That made it certain. They now knew that the Japanese would send a small force to the Aleutian Islands, as originally planned, but that the main target would be Midway.

Nimitz asked Simard and Shannon what they needed to protect the islands. They reeled off a long list. He asked Shannon: "If I get you all these things you say you need, then can you hold Midway against a major amphibious assault?" The reply was a simple "Yes, sir."³ Within a week anti-aircraft guns, rifles, and other war materiel arrived at Midway. Eastern Island was crowded with Marine Corps, Navy, and Army Air Force planes--fighters, small dive bombers, and larger B-17 and B-26 bombers. Every piece of land bristled with barbed wire entanglements and guns, the beaches and waters were studded with mines. Eleven torpedo boats were ready to circle the reefs, patrol the lagoon, pick up ditched airmen, and assist ground forces with anti-aircraft fire. Nineteen submarines guarded the approaches from 100 to 200 miles northwest and north. By June 4, 1942, Midway was as ready as possible to face the oncoming Japanese.

Questions for Reading 1

1. What did the Japanese hope to accomplish by occupying Midway?

2. What actions did the Americans take to protect the islands?

3. How did the Navy determine that Midway was the target for the Japanese fleet?

4. Why was it difficult to convince people in Washington that the information provided by the code breakers was correct?

Reading 1 was adapted from Erwin N. Thompson, "World War II Facilities at Midway" (Midway Islands, U.S. Minor Islands), National Historic Landmark documentation, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1986; Gordon W. Prange, Donald M. Goldstein, and Katherine V. Dillon, Miracle at Midway (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982); Edmund L. Castillo, Midway: Battle for the Pacific (New York: Random House, 1989); Edwin T. Layton, Roger Pineau, and John Costello, And I Was There, Pearl Harbor and Midway--Breaking the Secrets (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985); and the Naval Historical Center Web site.

¹ Gordon W. Prange, Donald M. Goldstein, and Katherine V. Dillon, Miracle at Midway (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1982), xiii.

² Edwin T. Layton, Roger Pineau, and John Costello, And I Was There, Pearl Harbor and Midway--Breaking the Secrets (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985), 422.

³ Prange, et al., Miracle at Midway, 74.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The Battle of Midway

By early June, the Japanese attacks on the Aleutians and on Midway were underway. The Midway attack force was divided into three parts. First the aircraft carriers would approach from the northwest and knock out the islands' defenses. Coming in from the west and southwest, the Second Fleet would invade and capture Midway. Admiral Yamamoto's battleships would remain 300 miles to the west, awaiting the U. S. Pacific Fleet.

Because of the work of the American code breakers, the United States knew Yamamoto's plans in detail by the middle of May: his target, his order of battle, and his schedule. When the battle opened, the U.S. had three carriers waiting in ambush, 200 miles to the east of Midway. The two opposing fleets sent out search planes; the Americans to locate an enemy they knew was there and the Japanese as a matter of ordinary prudence.

Seaplanes from Midway also were looking for the expected enemy fleet. One of the planes spotted the Japanese carrier force at about 5:30 on the morning of June 4. The plane also reported Japanese aircraft heading for the atoll. Marine Corps planes from Midway soon intercepted the enemy formation. However, the Marines were hopelessly outnumbered and their planes were no match for the Japanese "Zero" fighter planes. They were able to shoot down only a few of the enemy bombers, while suffering great losses themselves. The torpedo boats and anti-aircraft fire from Midway's guns were somewhat more successful in disrupting the Japanese attack.

One hundred and eight Japanese planes hit Midway's two islands at 6:30. Twenty minutes of bombing and machine-gun fire knocked out some facilities on Eastern Island, but did not disable the airfield there. Sand Island's oil tanks, seaplane hangar, and other buildings were set afire. The commander of the Japanese attack radioed that another air strike was required to soften up Midway's defenses for invasion.

The Japanese carriers received several counterstrikes from Midway's torpedo planes and bombers. Faced with overwhelming fighter opposition, these uncoordinated efforts suffered severe losses and hit nothing but seawater. The only positive results were photographs of three Japanese carriers taken by the high-flying B-17s, the sole surviving photos of the day's attacks on the Japanese carriers.

Meanwhile, a Japanese scout plane had spotted the U.S. fleet and reported the presence of a carrier. Japanese commander Nagumo had already begun loading bombs into his second group of planes for another strike on Midway. This news forced him to rethink his strategy. He decided to wait for the planes returning from Midway and rearm all the planes with torpedoes for an attack on the U.S. ships. He almost had enough time.

Beginning about 9:30, torpedo planes from the U.S. carriers Hornet, Enterprise, and Yorktown made a series of attacks that, despite nearly total losses, made no hits. Then, about 10:25, everything changed. Three squadrons of dive bombers, two from Enterprise and one from Yorktown, almost simultaneously dove on three of the four Japanese carriers, whose decks were crowded with fully armed and fueled planes. By 10:30, Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu were ablaze and out of action.

Of the once overwhelming Japanese carrier force, only Hiryu remained operational. Shortly before 11:00 she launched 18 of her own dive-bombers. At about noon, as these planes approached Yorktown, they were intercepted by U.S. fighter planes, which shot down most of the bombers. Seven survived, however, hitting Yorktown with three bombs and stopping her.

The Yorktown's crew managed to repair the damage and get their ship underway. Two more groups of torpedo planes and fighters from Hiryu soon spotted the Yorktown, which they mistook for a second U.S. carrier. Despite losses to the defending fighters and heavy anti-aircraft fire, the Japanese planes pushed on to deliver a beautifully coordinated torpedo attack. The stricken ship again went dead in the water. Concerned that the severely listing vessel was about to roll over, her captain ordered his crew to abandon ship. Late on June 4, U.S. carrier planes found and bombed Hiryu, which sank the next day. Two days later, a Japanese submarine located the Yorktown and the U.S. destroyer Hammann, which was helping the Yorktown return to Pearl Harbor for repairs. The submarine torpedoed both vessels. The Hammann sank immediately, and the Yorktown finally sank the following morning.

By the end of the battle, the perseverance, sacrifice, and skill of American pilots, plus a great deal of good luck, cost Japan four irreplaceable aircraft carriers, while only one of the three U.S. carriers was sunk. The Japanese lost 332 of their finest aircraft and more than 200 of their most experienced pilots. Deprived of useful air cover, and after several hours of shocked indecision, Yamamoto called off the Midway operation and retreated. The Japanese navy never fully recovered from its losses. Six months after it began, the great Japanese Pacific War offensive was over. From June 1942 to the end of the war three years later, it was the Americans who were on the offense.

Questions for Reading 2

1. What three elements were involved in the Japanese attack on Midway?

2. What damage was done to the islands in the Japanese attack?

3. How successful were Midway's counterattacks? Why?

4. What changed at 10:25? Admiral Nimitz later said that the dive-bombers were "worth their weight in gold." What did he mean by that?

Reading 2 was compiled from Erwin N. Thompson, "World War II Facilities at Midway" (Midway Islands, U.S. Minor Islands), National Historic Landmark documentation, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1986; Sidney C. Moody, Jr. and the Associated Press, War Against Japan (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1994); Edmund L. Castillo, Midway: Battle for the Pacific (New York: Random House, 1989); and the Naval Historical Center Web site.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Voices from Midway

The following are excerpts from reports and oral histories from participants in the Battle of Midway:

Commander John Thach, the leader of Yorktown's fighter pilots, was escorting torpedo planes attacking the Japanese carriers:

Several Zeros came in on a head-on attack on the torpedo planes.... In the meantime, a number of Zeros were coming down in a string on our fighters. The air was just like a beehive. I was utterly convinced that we weren't any of us coming back because there were still so many Zeros.... And then I saw a glint in the sun that looked like a beautiful silver waterfall. It was the dive-bombers coming in. I could see them very well because they came from the same direction as the Zeros. I'd never seen such superb dive-bombing. After the dive-bomber attack was over, I stayed there. I could only see three carriers. And one of them was burning with bright pink flames and sometimes blue flames. I remember gauging the height of those flames by the length of the ship, the distance was about the same. It was just solid flame going skyward and there was a lot of smoke on top of that. Before I left the scene I saw three carriers burning pretty furiously.

Thach later defended Yorktown during its attack by Japanese dive-bombers:

Now I saw a torpedo plane coming. I made a good side approach on him and got him on fire. The whole left wing was burning and I could see the ribs showing through the flames. But that devil stayed in the air until he got close enough and dropped his torpedo. That one hit the Yorktown. He was a dedicated torpedo plane pilot, for even though his plane was on fire and he was falling, he went ahead and dropped his torpedo. He fell into the water immediately after, very close to the ship. These Japanese pilots were excellent in their tactics and in their determination. In fact, as far as determination was concerned, you could hardly tell any difference between the Japanese carrier-based pilots and the American carrier-based pilots. Nothing would stop them if they had anything to say about it.

Mitsuo Fuchida commanded one of the Japanese carrier squadrons at Pearl Harbor, but did not participate in the action at Midway because he was recovering from an appendectomy. He observed the battle from Akagi:

Preparations for counterstrike against the enemy had continued on board our four carriers throughout the enemy torpedo attacks. One after another, planes were hoisted from the hangar and quickly arranged on the flight deck. At 10:24 the first Zero fighter gathered speed and whizzed off the deck. At that instant a lookout screamed: "Hell-divers!" I looked up to see three black enemy planes plummeting toward our ship. Some of our machine guns managed to fire a few frantic bursts at them, but it was too late. The plump silhouettes of the American Dauntless dive-bombers quickly grew larger, and then a number of black objects suddenly floated eerily from their wings. Bombs! Down they came straight toward me! I fell instinctively to the deck and crawled behind a command post mantelet.The terrifying scream of the dive-bombers reached me first, followed by the crashing explosion of a direct hit. There was a blinding flash and then a second explosion, much louder than the first. I was shaken by a weird blast of warm air. There was still another shock, but less severe, apparently a near miss. Then followed a startling quiet as the barking of guns suddenly ceased. I got up and looked at the sky. The enemy planes were already out of sight.

The attackers had gotten in unimpeded because our fighters, which had engaged the preceding wave of torpedo planes only a few moments earlier, had not yet had time to regain altitude. Consequently, it may be said that the American dive-bombers' success was made possible by the earlier martyrdom of their torpedo planes. We had been caught flatfooted in the most vulnerable condition possible--decks loaded with planes armed and fueled.

Looking about, I was horrified at the destruction that had been wrought in a matter of seconds. Planes stood tail up, belching livid flame and jet-black smoke. Reluctant tears streamed down my cheeks as I watched the fires spread. Explosions of fuel and munitions devastated whole sections of the ship. As the fire spread among planes lined up wing to wing on the after flight deck, their torpedoes began to explode, making it impossible to bring the fires under control. The entire hangar area was a blazing inferno, and the flames moved swiftly toward the bridge.

On June 28, 1942, Admiral Nimitz filed his official report on the battle:

In numerous and widespread engagements lasting from the 3rd to 6th of June, with carrier based planes as the spearhead of the attack, combined forces of the Navy, Marine Corps and Army in the Hawaiian Area defeated a large part of the Japanese fleet and frustrated the enemy's powerful move against Midway that was undoubtedly the keystone of larger plans. All participating personnel, without exception, displayed unhesitating devotion to duty, loyalty and courage. This superb spirit in all three services made possible the application of the destructive power that routed the enemy.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Why did Commander Thach think he would not survive?

2. What did Thach think about the Japanese pilots against whom he fought? Thach's account was recorded in 1971. Do you think his opinion might have been different in 1942? Why or why not?

3. What were Fuchida's feelings during the attack? How do you think you would have felt?

4. What role did the unsuccessful attacks of the torpedo planes play in the success of the dive-bombers?

5. How long did the attack of the American dive-bombers take? How do you think the course of the battle might have been affected if it had come after the Japanese planes had taken off?

6. Based on what you have read, do you think Nimitz's summary of the battle was accurate?

Reading 3 was compiled from John T. Mason, ed.,The Pacific War Remembered: An Oral History Collection (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1986), 103-105; and David C. Evans, ed., The Japanese Navy in World War II: In the Words of Former Japanese Naval Officers, 2nd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1986), 140-142. Admiral Nimitz's report was taken from the Online Action Reports of the Battle pages of the Naval Historical Center's Web site.

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Midway Atoll, 1941.

This photo shows Midway before the Pearl Harbor attack. Eastern Island is in the foreground with the somewhat larger Sand Island in the background.

Photo 2: Midway after the June 4, 1942 attack.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Locate the landing strips on Eastern Island. Why do you suppose the Japanese did not bomb this area?

2. Does Photo 1 or Map 2 give you a better sense of what Midway was like? Discuss.

3. Photo 2 shows damage caused by the Japanese air attack. Can you tell how serious this damage was? What effect do you think it might have had on the ability of the island to defend itself against the invasion planned for the next day?

4. Even though the invasion of Midway was one of the main objectives of the Japanese fleet, the bombing of the islands seems to have had virtually no effect on the outcome of the battle. Why do you think that might have been the case?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: Bombing of U.S. carrier Yorktown, 1942.

(National Archives and Records Administration)

Aircraft carriers were a new and untried weapon at the beginning of the war. Both the Japanese and American navies saw their big, heavily armed battleships as their primary offensive weapon. Because so many American battleships were lost on December 7, Admiral Nimitz was more or less forced to rely on his carriers, which were not at Pearl Harbor.

Questions for Photo 3

1. The carriers whose aircraft determined the outcome of the Battle of Midway were located hundreds of miles away from each other. What effect do you think that might have had on the battle?

2. Do you think the loss of the Yorktown affected the outcome of the battle?

3. Does this photo help give you a better sense of what the battle was like? If so, how?

4. The Yorktown was sunk as it was being slowly towed towards Pearl Harbor for repairs. Why do you suppose the Americans went to so much effort to try to save the vessel?

Visual Evidence

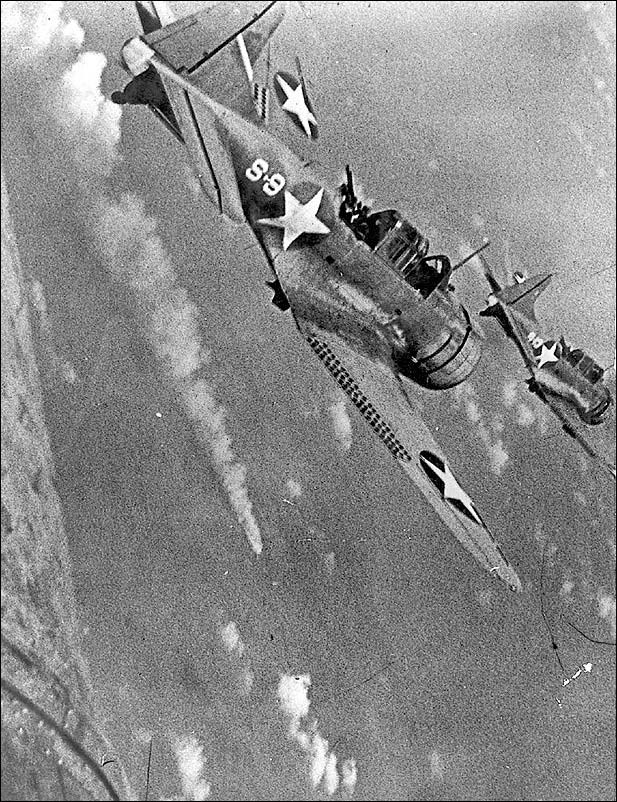

Photo 4: Dive-bombers attacking a Japanese ship, 1942.

Questions for Photo 4

1. Photo 4 shows dive-bombers attacking a Japanese cruiser. These were not large planes (about 32 feet long, with a wing span of 41 feet 6 inches). The crew consisted of a pilot and a rear seat observer/gunner, both in an open cockpit. Can you find the gunner's machine gun in this photo?

2. American pilots had pioneered the kind of dive-bombing where planes released their bombs at the end of a steep, high-speed dive. They preferred to attack from the direction of the sun. Why would this help them? What do you think piloting a dive-bomber would have been like?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Bombers on Midway, December 1942.

(National Archives and Records Administration)

The damage caused by the Japanese bombing was repaired by July 1942, when a new Naval Operating Base was established. By the middle of 1943, new, longer runways had been built on Sand Island and Midway's population had reached 5,000.

Questions for Photo 5

1. What appears to be happening in the photo?

2. Why do you think it was important to repair the damage incurred during the Japanese attack?

3. Why do you think Midway continued to play an important role in the American campaign in the Pacific? (You may want to refer back to Map 1.)

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Ammunition magazine on Midway.

(National Park Service, E. N. Thompson, photographer)

Photo 6 shows one of the surviving ammunition storehouses on Midway. It also shows some of the atoll's famous albatrosses. These birds stay out over the open ocean for months at a time, landing on the surface of the water only to fish and sleep. They come to Midway for mating and nesting. Their dramatic, ungainly mating dances led American GIs to call them "gooney birds." Collisions with the birds damaged hundreds of planes--sometimes seriously. The Navy tried to drive the birds off by blowing smoke from burning old tires. They tried to scare them with loud noises from mortars and bazookas. They shipped adult birds off to distant islands; the birds came right back. They hauled 2,000 baby albatrosses to an island 250 miles away; the adults came back to Midway, where they were born. Finally, the Navy gave up.

Questions for Photo 6

1. What might be some of the particular difficulties of constructing buildings at Midway?

2. How do you think the men stationed on Midway felt about the albatrosses?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students learn more about how technology has affected warfare and how wars are memorialized.

Activity 1: Victory or Defeat?

One student of the Battle of Midway attributed the American victory to intelligence, strategy, tactics, and luck.1 Have students review the information contained in this lesson and then hold a classroom discussion to decide which of these elements made the greatest contribution to the victory.

Activity 2: Technology and Warfare

Technological changes in weapons seem to be a race between offense, the ability to hurt the enemy, and defense, the ability to protect yourself. Have students work in groups of four or five to review the following list of technological developments that have affected warfare. Can they identify any patterns in these groupings? Ask them to consider questions such as: How have the weapons of war changed over time? How have "battlefields" changed over time in terms of scale? How has the physical relationship between enemies changed? Have one or two groups explain their answers to the class. Then hold a general class discussion on how weapons technology might affect attitudes towards making war.

|

Offensive Weapons: |

Defensive Weapons: |

|

swords |

shields |

|

spears |

armor |

|

gunpowder |

trenches |

|

cannons |

fortifications |

|

battleships |

submarines |

|

aircraft |

anti-aircraft guns and radar |

|

bombs |

bomb-proof shelters |

|

aircraft carriers |

more aircraft carriers |

|

nuclear bombs |

more nuclear bombs |

|

guided missiles |

anti-missile missiles |

Activity 3: Remembering the Battle of Midway

Explain to students that on September 13, 2000, Midway Atoll was designated as the Battle of Midway National Memorial. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service administers the Memorial. One monument to the battle has already been constructed. In January 2002, the Fish and Wildlife Service formed a planning committee to develop a strategy for a public dedication for the memorial and to plan commemorative exhibits. Ask students what they think should happen? Should structures surviving from the battle, like the magazine shown in Photo 6, be preserved? Why? How should they be marked and interpreted? What is the best way to commemorate a battle that took place at sea? Ask local veterans' groups if they can locate someone who participated in the Battle of Midway who would speak to the class about his experiences. Ask the veteran how he thinks the battle should be remembered.

Ask the students whether there is an alternate way to help Americans remember the battle given the difficulty of traveling to Midway. Can they think of an appropriate site for a memorial marker? Have them work in small groups to prepare an inscription of about 100 words that could be placed on an interpretive marker. Then have the class compare the groups' ideas and chose one they think best presents important information about the Battle of Midway.

1Edmund L. Castillo, Midway: Battle for the Pacific (New York: Random House, 1989), 149.

The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific, students learn about a fight over two tiny islands that affected the course of World War II. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge

Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge is maintained by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which administers the Battle of Midway National Memorial. Visit's the refuge's web pages for information on both the continuing work of maintaining and preserving the atoll's historic properties and on its abundant wildlife.

Naval Historical Center

The Naval Historical Center web site contains an excellent, detailed history of the Battle of Midway, historic photographs, primary documents, and oral history interviews. It also includes paintings from the Navy Art Collection recreating the battle.

National Security Agency

The National Security Agency web site contains a section on World War II cryptography that gives more detail on the breaking of the Japanese code.

Naval Postgraduate School

The Naval Postgraduate School web site of the Dudley Knox Library at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, CA, has compiled a bibliography for the Battle of Midway. It includes links to over 100 Web pages covering people, ships, and aircraft involved in the battle.

World War II Veterans

The World War II U.S. Veterans Web site contains information and services for veterans of World War II. Created by Dick Berry, a World War II Navy Veteran, and his son, the site has information regarding the proposed World War II U.S. Veterans Memorial Museum, a veterans forum, as well as World War II and 1940s memorabilia. The site also features various links that may be of interest such as The Veterans Administration and the Official U.S. Military Reunion Site.

Florida State University

The Institute on World War II and the Human Experience has a tremendous online archive of newspapers, photographs, letters, cartoons, ration cards, and more that help detail the history of Americans in World War II. The program is also gathering oral histories of veterans, their spouses, and others related to the defense industry.

Library of Congress: American Memory Collection

American Memory is a gateway to rich primary source materials relating to the history and culture of the United States. The site offers more than 7 million digital items from more than 100 historical collections. Use the search engine to find primary sources for World War II, Midway, and other related subjects.

The National Archives

The National Archives online exhibit hall feature, the Powers of Persuasion, explores the strategies of persuasion as evidenced in the form and content of World War II posters. Also see the Japanese Surrender document signed on September 2, 1945, by Japanese representatives. It was the official Instrument of Surrender, prepared by the War Department and approved by President Truman.

Tags

- battle of midway

- midway

- midway atoll

- world war ii

- world war ii pacific

- technology

- airplanes

- ship

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- early 20th century

- military wartime history

- u.s. in the world community

- military history

- mid 20th century

- twhplp

- us minor island