Last updated: April 12, 2023

Article

The Battle of Bentonville: Caring for Casualties of the Civil War (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

March 19, 1865, dawned soft and balmy in central North Carolina. A brass band played the hymn "Old Hundred." The hymn's tranquil strains reminded the 30,000 men on the Left Wing of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's Union army group that it was Sunday, while blossoming fruit trees called to mind quiet homes and families far away. Many of the soldiers looked forward to the end of the war, which now seemed imminent.

But the idle thoughts of a Sunday morning exploded as the Federals approached the farming community of Bentonville. Just outside of town 20,000 tattered Confederates, the remainder of a once-powerful army, attacked the Union troops. Dreams of joyous reunions were soon replaced by the carnage of war, and men who had marched to the front now lay wounded on the battlefield.

Four years earlier, at the beginning of the war, these men might have remained, untreated, on the battlefield for days. At the First Battle of Manassas in 1861, for example, many Union doctors fled in fear and those who stayed found themselves without adequate supplies or ambulances for their patients. As the war progressed and casualties mounted, however, military surgeons became more adept at caring for wounded. By the Battle of Bentonville, one of the last major engagements of the Civil War, the United States Army Medical Department had developed an effective system for operating field hospitals and an ambulance corps. This improved organization was typical of the advances in logistics that helped the North's war effort.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Bentonville Battleground State Historic Site" (with photographs), and other sources. It was made possible by the National Park Service's American Battlefield Protection Program. The lesson written by John C. Goode, Historic Site Manager at Bentonville Battleground State Historic Site, and Elaine Beck, Curator of Education for the North Carolina Historic Sites Section. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in units on the Civil War. Students will strengthen their skills of observation, research, and analysis of a variety of sources.

Time period: Late 19th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

The Battle of Bentonville: Caring for Casualties of the Civil War relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

Standard 2A- The student understands how the resources of the Union and Confederacy affected the course of the war.

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the social experience of the war on the battlefield and homefront.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

The Battle of Bentonville: Caring for Casualties of the Civil War relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationships to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants and security.

-

Standard D - The student explains the need for laws and policies to govern scientific and technological applications, such as in the safety and well-being of workers and consumers and the regulation of utilities, radio, and television.

Theme X: Civic Ideals, and Practices

-

Standard C - The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues - recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

Objectives for students

1) To trace how the Union Army's organization of medical care in the field developed between the battles of First Manassas in 1861 and Bentonville in 1865.

2) To identify criteria considered important by Union surgeons in determining locations for the placement of field hospitals.

3) To understand the experience of a wounded soldier at the end of the Civil War, from his removal from the battlefield through his treatment at a field hospital.

4) To examine how a battle affected nearby families.

5) To gather information on the experiences of members of volunteer service organizations or the medical profession within their community who have been involved with trauma-related situations.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

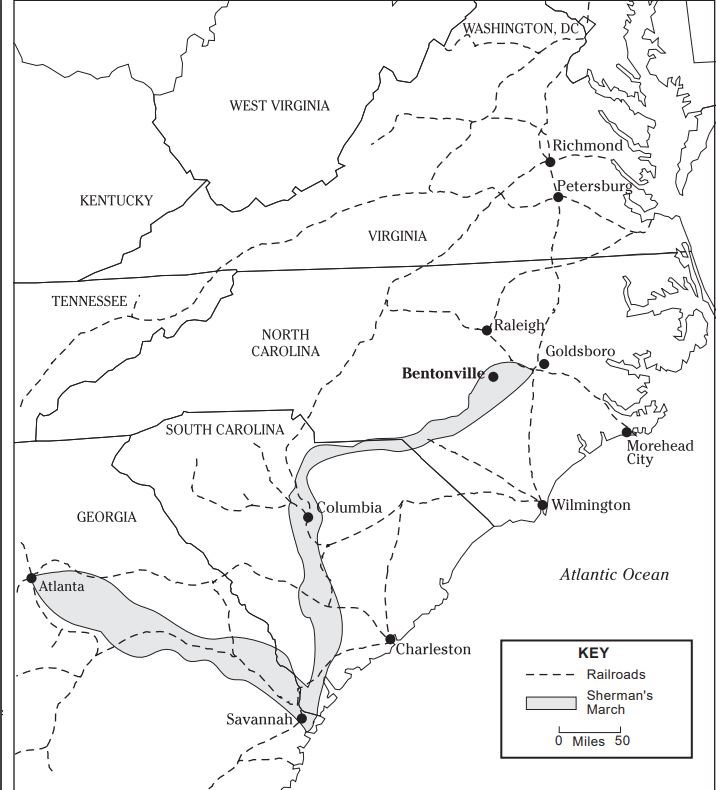

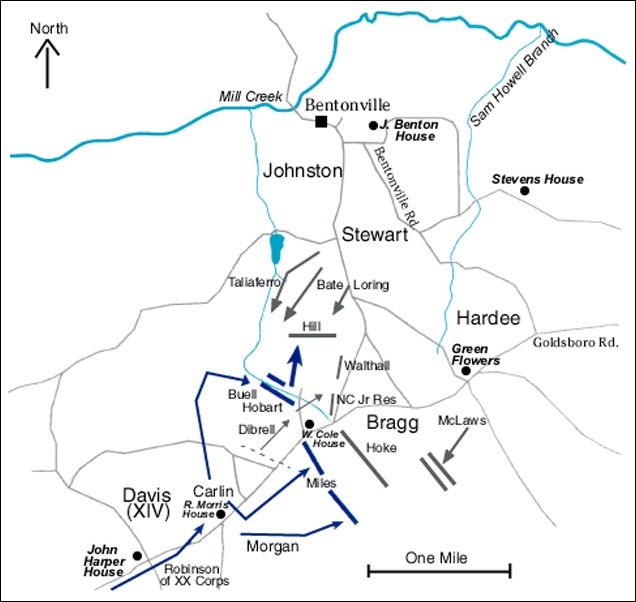

1) two maps showing Sherman's march and the Battle of Bentonville;

2) four readings demonstrating the development of Union medicine during the Civil War, including several personal observations;

3) three photos of field medicine, an army hospital, and the Harper House.

Visiting the site

Of the 6,000 acres on which the Battle of Bentonville occurred, only 120 are maintained today as Bentonville Battleground State Historic Site. The battleground is maintained by an agency of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It is located in southeastern Johnston County on State Road 1008, six miles east of Interstate 40 and 15 miles southeast of Interstate 95. There are marked exits for the battlefield on both interstates. From April 1 through October 31, the site is open Monday-Saturday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., and on Sunday from 1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Winter hours are in effect from November 1 through March 31, when the site is open Tuesday-Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., and 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. on Sunday. The site is closed on Monday during its winter schedule, as well as on New Year's Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. For additional information, contact the Historic Site Manager, 5466 Harper House Road, Four Oaks, North Carolina, 27524.

| |

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What does this place appear to be?

When might this photograph have been taken?

Setting the Stage

After the fall of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, 60,000 Union soldiers under the command of Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman marched more than 1,000 miles through the South. By March 1865, they were in the middle of North Carolina, heading north with the intention of joining forces with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Grant's men, now besieging the Confederate capital of Richmond, were just 75 miles away. As part of his attempt to defend Richmond and nearby Petersburg, Gen. Robert E. Lee assigned Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to stop Sherman's forces from entering Virginia.

In central North Carolina Johnston managed to piece together a ragtag army of 20,000 men. He maneuvered to take advantage of Sherman's decision to divide his army into two columns to increase its mobility. On the morning of March 19, just south of the village of Bentonville, Johnston attacked Sherman's Left Wing, which had fallen half a day behind the Right. Although this offensive made considerable progress, Union troops staged a resolute defense that afternoon to prevent a Confederate breakthrough. The other half of Sherman's army arrived the next afternoon, and the battle continued until Johnston withdrew from the field on the night of March 21. The three days of fighting involved more than 90,000 men and ranged across nearly 6,000 acres of land. General Johnston's attack, which took place just three weeks before General Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House, was the only major attempt to stop Sherman's army after Atlanta and the last Confederate offensive.

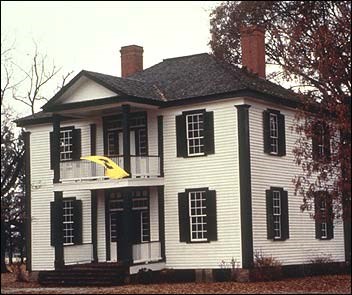

The Battle of Bentonville, as it became known, resulted in more than 4,000 casualties. Many of the wounded found themselves in a field hospital set up by Sherman's Fourteenth Army Corps. Its surgeons, searching for a safe location, chose the modest two-story farm home of John and Amy Harper, and wounded began streaming to this makeshift medical facility within minutes of its establishment a mile from the chaotic front lines. Throughout March 19 and 20, Federal surgeons at the Harper House treated a total of 554 men, both Union and Confederate. Without the benefit of antibiotics to stop infection, doctors amputated shattered arms and legs to prevent gangrene from claiming their patients' lives. Despite the screams of the wounded, the piles of severed limbs, and the stench of blood and chloroform (an anesthetic used by Union surgeons) that pervaded the Harper House, the family refused to leave their home during this time.

Locating the Site

Map 1: General Sherman's march.

Questions for Map 1

1. Through which states did Sherman's army march? Which major cities did they capture?

2. Now concentrate on North Carolina. Locate Wilmington and Morehead City, both of which the Union had captured earlier in the war, and Goldsboro, which remained in Confederate hands.

3. Why would Sherman consider Goldsboro his primary objective in the state?

4. Why would the control of Wilmington and Morehead City have made the Union want to take Goldsboro even more?

Locating the Site

Map 2: Bentonville Battlefield.

This map shows the fighting on March 19, 1865, the first day of the Battle of Bentonville. The arrows indicate movement of troops. The solid lines indicate the different positions where troops were stationed to fight.

Questions for Map 2

1. How close did the fighting come to the Harper House?

2. Why might the Harper House have been chosen as the field hospital over the other homes and structures in the map during the Battle of Bentonville?

3. How do you think the injured were evacuated from the battleground?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: From Incompetence to Proficiency: The Development of Union Medical Care

The North and the South had struggled through nearly four years of brutal fighting by the time the Battle of Bentonville erupted in the spring of 1865. By then, month after month of dead and wounded soldiers had drained away most, if not all, of the romance of war that had characterized the start of the conflict. Yet the seemingly endless flood of casualties had produced at least one encouraging development, better medical care on the battlefield.

For troops wounded in the early battles of the Civil War, the disorganization of the medical corps often proved disastrous. At the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run) on July 21, 1861, for example, many Union surgeons refused to treat casualties from regiments other than their own, and civilian ambulance drivers fled from the field at the first sound of gunfire. As a result, some wounded were left lying on the battlefield for three or four days.

Assistant Surgeon John W. Foye of the Eleventh Massachusetts Infantry described one deplorable but typical scene:

The regiment was accompanied by one ambulance well provided with stimulants and surgical appliances, but without medicines or tents. The field hospital was established about a quarter of a mile from the front line when we engaged, but late in the day it was three-quarters of a mile in the rear. Up to two o'clock the Confederate wounded at the hospital nearly equaled our own. Until that time but few wounded were brought off by their comrades, but later it was not unusual to find a flesh wound escorted by half a dozen able men....At three a medical officer of rank visited the hospital on his way to the rear and left it optional with the medical officers at the hospital to join him or remain. Nearly all the surgeons left us about half-past three. Three ambulances went away at that time. The only remaining ambulance, belonging to my regiment, was captured about half-past five, within a hundred yards of the hospital. All the wounded capable of being moved had been sent off to the rear. I estimate the number left at one hundred and eighty. All of them fell into the hands of the enemy.¹

The horror and suffering at Manassas led administrators within the United States Army Medical Department to urge the formation of an ambulance corps and a formal system for establishing and operating field hospitals during battle. Many of the necessary improvements were provided by Surgeon Jonathan Letterman, Medical Director of the Union's Army of the Potomac. Part of the following reading comes from his "Field Hospital Order" of October 30, 1862; the rest appeared in guidelines given to the Medical Director of an Army Corps.

Previous to an engagement, there will be established in each Corps a hospital for each Division, the position of which will be selected by the Medical Director of the Corps. There will be selected from the Division, by the Surgeon-in-Chief...three Medical Officers, who will be the operating staff of the hospital, upon whom will rest the immediate responsibility of the performance of all important operations....

The remaining Medical Officers of the Division...who follow the regiments to the field will establish themselves, each one at a temporary depot, at such a distance or situation in the rear of his Regiment as will insure safety to the wounded, where they will give such aid as is immediately required....

The Surgeon-in-Chief of Division will exercise general supervision...over the medical affairs of his division. He will see that the officers are faithful in the performance of their duties in the hospital and upon the field, and that, by the ambulance corps...the wounded are removed from the field carefully and with dispatch.

During an engagement the duty devolving upon the Medical Director of a Corps to select a site for the different hospitals of the Corps is not always an easy one. As a general rule they should be placed near the most practicable roads, in rear of the center of the troops, and sufficiently to the rear to be out of the ordinary range of the enemy's guns; suitable ground, good water, and plenty of fuel must of course decide the choice of locality.²

This system, which became known as the Letterman Plan, was introduced first in the East. It became a crucial part of the North's gradual improvement of its logistics--its handling of military material, facilities, and men. In 1862 the South set up its equivalent of the Letterman Plan, an "infirmary corps." In Battle Cry of Freedom James McPherson points out that, "like everything else in the southern war effort, [the infirmary corps] did wonders with the resources available but did not have enough men, medicines, or ambulances to match the Union effort." As a result, he estimates, 14% of wounded Federal troops died versus 18% of wounded Confederates.³

The Letterman plan was still untried in the Union's western armies when General William T. Sherman commenced his Atlanta Campaign in the spring of 1864. But by the time Sherman began his "March to the Sea" in November 1864, it was working well and in many instances had even been refined.

Questions for Reading 1

1. What problems did the Union Army Medical Corps have during the First Battle of Manassas?

2. At that battle, what option did the ranking medical officer give the surgeons when he visited the field hospital? How did they react? Why do you think the surgeons made this decision? Why do you think "half a dozen able men" frequently chose to escort someone with a flesh wound to the hospital?

3. According to the Letterman Plan, what were the duties of the Medical Director of the Corps? The Surgeon-in-Chief? The medical officers assigned to regiments in the field?

4. Which problems apparent in the First Battle of Manassas did the Letterman Plan attempt to solve?

Compiled from Capt. Louis C. Duncan, The Medical Department of the United States Army in the Civil War (Washington, 191?) 29, 123-25; George A. Otis and D.L. Huntington,The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Part III, Vol. II, "Surgical History," Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883, 905.

¹Quoted in Capt. Louis C. Duncan The Medical Department of the United States Army in the Civil War (Washington, 191?), 29.

²Duncan, 123-125; Otis George A., and D.L. Huntington. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Part III, Vol. II, "Surgical History." (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1883), 905.

³James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford University Press: New York, 1988), 485.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Fighting and Treatment at the Battle of Bentonville

The Battle of Bentonville was one of the last major fights in the Civil War. The following report from Surgeon John H. Moore, one of Gen. William T. Sherman's medical officers, showed how care and treatment had changed since First Manassas.

On the 19th of March a fierce attack was made by the whole rebel force, under Gen. Joe Johnston, upon the advance and flank of the marching column of the Left wing.The wounded were well cared for in hospitals erected about half a mile in rear of the front or line of battle. On the 19th they came under fire and had to be removed.

Although this battle occurred nearly at the close of a long march--of two month's duration, without an opportunity of replenishing supplies--there was no lack of any article essential to the comfort of the wounded. Most of those wounded on the 19th were made as comfortable as possible in wagons and moved on the 20th to the vicinity of the Neuse river, opposite Goldsborough, a distance of about twenty-five miles. Army wagons were used in consequence of a scarcity of ambulances.

On the march the system of division hospitals was kept up and found to work well....After the last two battles some inconvenience was felt, owing to the deficiency of ambulances. Most of those in use in this army were supplied during the first year of the war and are worn out. One hundred new ones have been received here. No instance of serious neglect of duty on the part of the medical officers has come to my knowledge, but on the contrary they have been faithful and zealous in the performance of duty, and the wounded have been promptly removed from the field to the hospitals. The new system of ambulance organization has been more or less completely carried into effect in all the corps and has worked well. The character of the wounds in the cases of those brought to the hospitals was of an unusually grave character, much of the firing being at short range. Of the 1,368 wounded brought to the hospitals 131 died within forty-eight hours. There were eighty-eight capital amputations in cases brought to the hospitals from the battles of the 16th and 19th of March.¹

Questions for Reading 2

1. Based on the background information given, where was Sherman's army heading at the time of the Battle of Bentonville? Why?

2. Compare and contrast Reading 1 and Reading 2. Which problems in 1861 had the Union solved by 1865?

3. Per Moore's report, do you think the Letterman Plan saves lives? Why?

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Wounded on the Field of Battle

Lt. M.W. Bates served with the 21st Michigan Volunteer Infantry during the Battle of Bentonville. The 21st Michigan, one of three regiments in Col. George P. Buell's brigade of the Union's Fourteenth Army Corps, was among the first to encounter the main Confederate line during the battle. After a futile attempt to assault the Confederate line, during which the 21st Michigan suffered heavy casualties, Lieutenant Bates observed one of the first field hospitals established on the battlefield being evacuated to the rear:

Hospital quarters had been established on the bank of the small stream in our rear, the nearness to the line, and falling mini balls compelled its removal. When the ambulance came up to take in the wounded, the driver became demoralized and jumped from his seat to cut the traces and fly, Dr. Avery drew his revolver and held the driver to his work, and got off safely.

Later in the day, the Confederate army counterattacked the Union lines, and Bates's brigade was broken and routed. Bates was wounded during this attack, and eventually carried to the Fourteenth Army Corps field hospital located in and around the Harper House. The following account details Bates's experiences after his wounding. The specific nature of Bates's wound is not known, but we may assume from the comments of the surgeons that the wound was serious.

It was now about three o'clock....We could see their skirmishers thrown far out on our left in the open field, and soon the Confederates swarmed over their works.As far as we could see on both right and left, they were coming in unbroken lines....We held our position, keeping up a continuous and rapid fire, until we could plainly see their trap closing around us as they enveloped our flanks and subjected them [our flanks] to their fire. It was impossible to maintain our position and Gen. Buell reluctantly gave the order to fall back fighting as we retreated.

[There] was a low wet place through which we passed, then turned again for a last stand....It soon became apparent to us, that we could not hold our position, and we began to fall back into the open field on higher ground...as the rebels broke through the woods in perfect line and yelling like demons. Lt. Sears of [Company] H and [myself], waited where we made our last stand until the colors and the last of our men had started, we could not have been over ten rods from the rebel lines when they fired their first volley and [I] fell. Sears helped [me] to [my] feet, but [I] could not stand and falling again, began to crawl off with a sickening dread of being captured, fainting and craving water. Two of our men passing just then, lifted [me] between them, carried [me] to a fence corner just behind the guns, and laid [me] down.

How long I lay in that fence corner I do not know, or when I was removed. The next morning I found myself lying on my back in a tent filled with wounded men, the one next to me on my left dead. Our surgeon, Dr. Goodale, was looking at me, and with a cheery 'good morning,' wanted to know how I felt. I don't know what answer I made him, I was conscious that I was in a critical condition, and thought of my dear ones at home, thankful that I still had a fighting chance for life.

During that forenoon my brother hobbled in to the tent to see me, and I think every one of the line officers able to get there, also Dr. Avery, in company with the Corps surgeon, who, after looking at me, and inquiring of Dr. Goodale what he was doing for me, remarked 'nothing more can be done for him.' I knew my chances were slim, and after my friends had gone out of the tent, I heard some of them saying they would have to leave me there and I remember recording a vow that I would not fill a North Carolina grave then, and I think that resolution saved me.

How long I lay in that tent I cannot tell, I think all that day and the next night. I remember being placed in an ambulance with Lieut. Lyon, lying flat on the bottom side by side, for a ride of twenty miles to Goldsboro. To you who know the condition of the roads at the time and place, any description of that ride is unnecessary, the army had passed over it with the artillery and wagon trains, it was much of the way corduroyed [covered with logs laid across the road], the high water having misplaced many of the logs, our ambulance dropped through between them striking on the axle forcing us both with a bump against the head board, and then as the hind wheels followed, our heads striking the foot board, then a side lurch shaking up from side to side and against each other all that weary day and far into the night. May I never have another such ride. We remained in Goldsboro until well enough to be moved to New York.

(Bates was carried by rail to Morehead City, then by boat to New York.)

Questions for Reading 3

1. How did the ambulance driver observed by Lt. Bates and Dr. Avery behave under fire? Were each of these men acting within the guidelines established in the Letterman Plan for the conduct of medical officers and personnel?

2. What response did Dr. Goodale give when asked about Lt. Bates's condition? Why did the surgeon make this statement? Why do you think surgeons did not attempt to operate on severely wounded patients?

3. Lt. Bates survived his wounds, even though they were thought to be fatal. To what does Bates attribute his survival? Do you think it is possible to evaluate the accuracy of his belief?

Compiled from Lt. M.W. Bates Glimpses of the Nation's Struggle: Papers Read Before the Minnesota Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, 1897-1902 (St. Paul, Minnesota: Review Publishing Company, 1903), 146-151.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: Victims of Circumstance: Ordeal of the Harper Family.

John and Amy Harper were a middleclass farm couple who resided near the village of Bentonville prior to and during the Civil War. John's family originated in Virginia, where his great-uncle, Robert Harper, established a ferry and mill that eventually developed into the community known as Harpers Ferry. In addition to serving as a clerk in the county court system, John Harper also farmed approximately 100 of his 825 acres of land, primarily growing corn, peas, beans, and sweet potatoes. An unspecified portion of Harper's forest land was utilized in the production of turpentine, which was distilled from the rosin of pine trees. The family was active in the local Disciples of Christ Church, and so donated some of their land for the site of the Mill Creek Christian Church. Sometime between 1855 and 1859, John Harper constructed a new, two-story frame home for his growing family of nine children.

The Harpers had little time to enjoy their new home before the dark clouds of civil war disrupted the family's peaceful existence. Although eldest son John, Jr., an ordained minister in the Disciples of Christ Church, remained near his family during the Civil War, their second-oldest son enlisted in the Confederate army in 1861 at age 16. Martin was wounded in the Battle of South Mountain, Maryland, in September 1862, but remained in the army until the end of the war.

In the spring of 1865, the suffering of war literally came to the Harpers' front door. On March 19, 1865, the Battle of Bentonville erupted barely one mile east of their home. As the battle developed, Confederate attacks overran large portions of Union lines, and forced Union field hospitals to seek safer locations. Surgeons of the Union's Fourteenth Army Corps arrived at the Harper House and commandeered the structure for use as a field hospital. Its location met the standards of the Letterman Plan, for it was located in what was considered a safe distanceone milefrom the front lines.

John and Amy, along with the six children still living at home, were forced to take refuge in the upstairs rooms of the house while surgeons employed the downstairs rooms as makeshift operating theaters. "A dozen surgeons and their attendants in their shirt sleeves stood at rude benches," wrote one Union commander, "cutting off arms and legs and throwing them out of the windows where they lay scattered on the grass. The legs of the infantrymen could be distinguished from those of the cavalry by the size of their calves, as the march of 1,000 miles had increased the size of one and diminished the size of the other."¹ There were at this time no antibiotics to stop infections, and so the only way to prevent gangrene from killing patients was to amputate shattered arms and legs. But despite the screams, the piles of severed limbs, and the smell, the Harper family refused to leave their home.

When the battle was over, the Union surgeons removed their wounded from the home, but left behind in the Harpers' care 45 wounded Confederate soldiers. These men were given the best the family could provide. John Jr. later recalled that his parents had acted as "nurses, surgeons, commissaries, chaplains and undertakers. My mother fed them, washed their wounds, pointed them to the Saviour, closed their eyes when all was over, and helped to bury their uncoffined bodies as tenderly as she could." John Jr. joined his parents at the Harper House, helping them comfort the wounded and dying of both armies. Evidence suggests that 26 of the wounded Confederates were eventually removed from the house by Confederate surgeons, but 19 men succumbed to their wounds and were buried by the family.

After Sherman's army continued its march to Goldsboro, Confederate cavalry units returned to the Bentonville area to picket the roads in the vicinity. Scouts from one of these regiments, the First Kentucky, were the first to discover that wounded Confederate soldiers had been left in the home of John and Amy Harper. One week after the battle, the letter below was directed to Confederate General Johnston's headquarters calling attention to the plight of the wounded at Harper House.

Headquarters, 1st Ky. Cav.

Near Bentonville, Mar. 27, 1865

Lt. Col. Anderson,

Assistant Adjutant-Gen.:

COLONEL: My scout sent (in charge of Sergeant Ellis of this regiment) to the battlefield near Bentonville has returned. He reports finding none of the wounded of the enemy left. There are 45 wounded of our army at the house of Mr. Harper (exclusive of those left at Bentonville). They are in a suffering condition for the want of proper supplies, and there is no surgeon to attend them. Mr. Harper and family are doing all their limited means will allow for the sufferers. Their wounds have been dressed and six or eight amputations performed skillfully by the surgeons of the enemy. There were no supplies left either with the wounded or in the country. There are no marks left by which the loss of the enemy can be estimated. Citizens report that they employed all their ambulances and 200 wagons constantly and actively, from Sunday afternoon until Tuesday night, removing their dead and wounded.

J.W. Griffith,

Lt. Col., Commanding Outpost

Questions for Reading 4

1. Is there any evidence to suggest that the Harpers had a choice as to whether or not the Union surgeons established a field hospital in their home? Is there evidence to suggest that they were financially compensated for the use of their home?

2. What did the Harper family do during the Battle of Bentonville? Why do you think they made that choice? What experiences or beliefs did the Harpers have that may have guided them in their decision to aid the wounded and abandoned soldiers in their home after the battle?

3. Which soldiers did Union surgeons treat at the Harper House field hospital? Why do you think wounded Confederate soldiers were taken to the Union field hospital for treatment? What type of care do they appear to have received? If you had been a wounded soldier, would you want to have been taken to the enemy's hospital for care? Explain why, or why not.

4. How were the Union and Confederate wounded at the Harper House treated differently after the battle and the departure of the Union army from the area? Why do you think the Confederate wounded were not taken as prisoners? Why do you think Confederate authorities did not respond to this situation sooner?

Compiled from the "Harper House Research Report," Historic Sites Sections, North Carolina Division of Archives and History.

¹Quoted in Jay Luvass, "Johnston's Last Stand--Bentonville," in North Carolina Historical Review XXXIII, No. 3 (July 1956), 332.

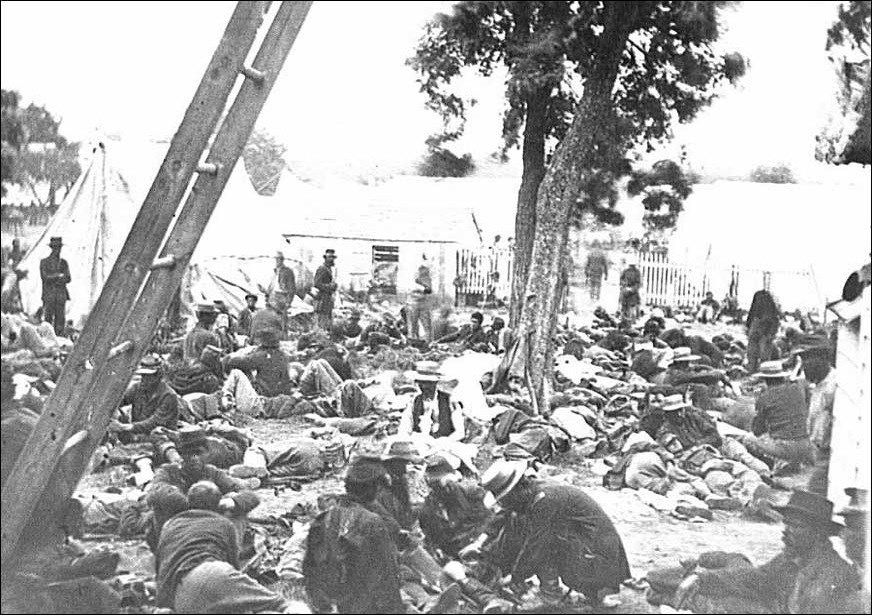

Visual Evidence

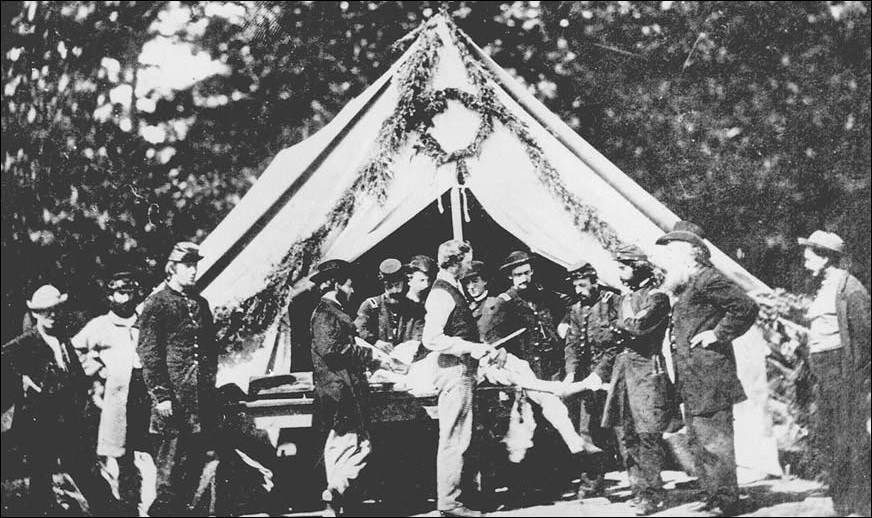

Photo 1: Amputation being performed in a hospital tent, Gettysburg, July 1863.

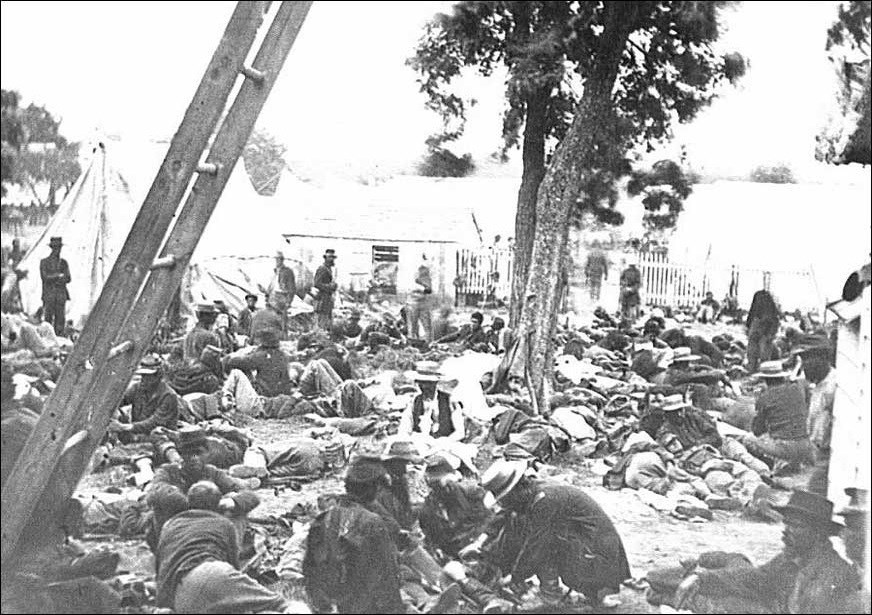

Photo 2: Field hospital after the battle, Savage Station, VA, 1862.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-B811-0491)

The Civil War was the first war in which the horror and death of the battlefield was extensively recorded by photographers. Even the gruesome scenes of field hospitals did not escape the camera's eye. Although there were no photographers traveling with Sherman's army at the time of the Battle of Bentonville, much can still be learned about field hospitals by examining photographs taken at other locations.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Write a separate description for each scene. Note things like the setting, the number of people, what they are doing, how they are dressed, and so on.

2. How do the differences of the two scenes indicate the changes made as a result of the Letterman plan?

3. How do the conditions exhibited in Photo 2 differ from modern operating room? Would surgery during the Civil War have "done more harm than good?"

Visual Evidence

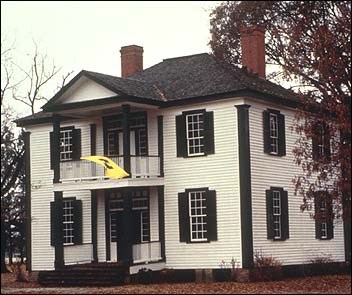

Photo 3: The Harper House.

(Bentonville Battleground State Historic Site)

Questions for Photo 3

1. What features of the house might have been useful to the army surgeons? Describe how the items identified might be used in a field hospital.

2. Review the description of the Harper House in Reading 4. What do you think the house looked like at the end of the day of March 19? What do you think the area outside the house looked like?

Putting It All Together

The four years of fratricidal war killed more then 620,000 Americans. These numbers would have been even higher had the two armies not improved their methods for getting the wounded to treatment. The systems developed during the Civil War proved so effective that they have continued to serve as the basis for army field hospitals: the structure of medical "Collecting and Clearing" units mobilized by the United States forces in 1991 during Operation Desert Storm, for example, may be traced to Civil War precedents, such as the hospital set up at the Harper House during the Battle of Bentonville.

Even with the many improvements both during and since the Civil War, however, wounded soldiers suffered. The following activities will help students better understand the experiences of those wounded in battle, and those who treated them.

Activity 1: Once a Soldier

Ask students to imagine they are farmers who enlisted in the Union army in 1862 that came through unscathed during the campaign for Atlanta and the March to the Sea. Marching with Sherman's army as it nears Goldsboro, North Carolina, they should think about the end of the war, which seems inevitable, and returning home to plow their fields in order to provide for their families. Suddenly they find themselves in the Battle of Bentonville where they receive a severe leg wound. They are carried to the field hospital at the Harper House, where a surgeon amputates their leg above the knee. Have students write a letter to their loved ones describing their experience, including the wounding, the treatment they received at the field hospital, and how they believe the wound and its treatment will change all of their lives.

Activity 2: The Other Side

Although this lesson concentrates on the advancements made in the Union medical service, the South also recognized the need for better treatment of its wounded. Ask students to research the system the Confederates arranged for their men, concentrating on how the Confederate system for transporting and treating the wounded compared to the North's. What were the reasons for the similarities and differences? To what extent did the successes and weaknesses of the Confederate medical service reflect the entire Southern war effort?

Activity 3: On the Homefront

Explain to students that war not only affects those who fight, but also those who live near the battlefields as well. The Harper family left no written record regarding their experiences during the Battle of Bentonville. Yet the battle was perhaps the most dramatic event of their lives. Lead the class in a discussion of the impact of such an event on the Harpers and other families who may have been caught in the midst of the fighting.

As a follow-up activity, ask students to survey news sources to identify any locations in the world today where families are being caught in the crossfire of an armed conflict. Students should think of ways in which these families try to cope with such dangerous situations.

Activity 4: A Popular Example

Perhaps one of the most powerful depictions of a modern-era army field hospital was the long-running television series M*A*S*H. Select an appropriate episode from that series (which is now commercially available on videocassette) for students to view. Have students compare and contrast the Korean Conflict-era field hospital depicted in M*A*S*H with the Civil War-era field hospital depicted in this lesson plan. They should pay particular attention to the surgeons depicted in the series, and identify their characteristics. Would the qualities depicted in the television characters (humor, humanity, etc.) have been necessary for a Civil War field surgeon as well? Students should design an enlistment poster recruiting doctors for service as field surgeons in the Union army during the Civil War.

Activity 5: In Your Own Community

The modern armed forces of the United States still employ field hospitals on the battlefield today. Ask students to investigate any mobile military hospitals (either at Regular Armed Forces military bases, or at local National Guard armories) based in their area. If such a military medical organization can be located, invite a representative of that unit to visit the class and discuss with the students modern military medical practices in the field. If such a medical unit cannot be located, contact a local physician and invite that person to speak to the class on modern forms of treatment for traumatic injuries. Students should compare these discussions with what they learned about medical care on Civil War battlefields. Unfortunately, all wars result in wounded soldiers. Locate veterans of foreign wars residing in the community who may have suffered service-related injuries. If they (the veterans) are agreeable, have students interview these veterans about their experiences.

Volunteers, like the Harper family, are often involved in crisis situations. Ask students to locate people in the community who have volunteered to help in such emergencies (for example, Red Cross volunteers, firefighters, hospital volunteers, and emergency medical personnel). Students should prepare a case study of one such individual, concentrating on that person's motivation for volunteering in extreme circumstances.

The Battle of Bentonville:Caring for Casualties of the Civil War--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at The Battle of Bentonville: Caring for Casualties of the Civil War, students can more easily understand how battlefield medical care developed during the Civil War, particularly in the Union Army. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of materials.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress created a selected Civil War photograph history in their "American Memory" collection. Included on the site is a photographic time line of the Civil War covering major events for each year of the war.

The Valley of the Shadow

For a valuable resource on the Civil War, visit the University of Virginia's Valley of the Shadow Project. The site offers a unique perspective of two communities, one Northern and one Southern, and their experiences during the American Civil War. Students can explore primary sources such as newspapers, letters, diaries, photographs, maps, military records, and much more.