Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

The Battle of Bennington: An American Victory (Teaching with Historic Places)

(Collections of The Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

During the summer of 1777, the British put in motion an ambitious campaign designed to isolate New England from the rest of the colonies and thereby crush the American rebellion. For two months, General John Burgoyne led his army down the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor toward Albany with apparent ease, capturing several American forts along the way. In August, however, he found himself in desperate need of provisions, wagons, cattle, and horses. Burgoyne then made the fateful decision to send an expeditionary force to the small town of Bennington, Vermont to capture these much needed supplies.

At the Battle of Bennington, which took place between August 14 and 16, the British army and its Canadian, Indian, and Loyalist supporters faced Patriots defending their newly proclaimed independence. What might have seemed like a minor victory for the Patriots contributed to the British defeat at Saratoga a few months later and thus helped decide who would win the American War of Independence.

About This Lesson

The lesson is based on the National Historic Landmark documentation file, "Bennington Battlefield" (with photographs), and on Philip Lord, Jr.'s War over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement Patterns on the Bennington Battlefield--1777. It was written by Kathleen Hunter, an educational consultant, and edited by Fay Metcalf, Marilyn Harper, and the Teaching with Historic Places Staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in American history, social studies, and geography courses in units on the Revolutionary War.

Time period: 1777

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

The Battle of Bennington: An American Victory relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

-

Standard 1C- The student understands the factors affecting the course of the war and contributing to American victory.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

The Battle of Bennington: An American Victory relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard C - The student explains and give examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard A. The student relates personal changes to social, cultural, and historical contexts.

-

Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard A - The student examines issues involving the rights, roles and status of the individual in relation to the general welfare.

-

Standard D - The student describes the way nations and organizations respond to forces of unity and diversity affecting order and security.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard B - The student identifies and interprets sources and examples of the rights and responsibilities of citizens.

-

Standard C - The student locate, access, analyze, organize, and apply information about selected public issues recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard D - The student practice forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

-

Standard E - The student explain and analyze various forms of citizen action that influence public policy decisions.

-

Standard G - The student analyze the influence of diverse forms of public opinion on the development of public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard J - The student examine strategies designed to strengthen the "common good," which consider a range of options for citizen action.

Objectives for students

1) To identify the groups who participated on both sides of the Battle of Bennington.

2) To describe the physical characteristics of the area around the Bennington Battlefield and determine the effect of geography on the outcome of the battle.

3) To evaluate the relative importance of manpower, motivation, and leadership in the outcome of a military conflict.

4) To identify evidence in their own community of local commitment to a cause.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps showing New England and the British Northern Campaign of 1777;

2) three readings about the battle and its participants;

3) two illustrations showing an artist's conception of the battle and troop positions during the battle.

Visiting the site

The Bennington Battlefield is part of the New York State park system. It is located near Hoosick Falls on Route 67 off Scenic Route 22, two miles from the Vermont border. The park is open to the public from May through October. For more information, contact the Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site, c/o Grafton Lakes State Park, PO Box 163, Grafton, NY 12082, or visit the New York State Park's web pages.

Bennington Battle Monument in Old Bennington, Vermont is a short ride from Bennington Battlefield. From the battlefield, follow Route 67 south to Route 7 east to Route 9 towards Bennington. Route 9 becomes Monument Ave. in town, which will leads to the monument.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What do you think this illustration is depicting?

Setting the Stage

After July 4, 1776, the people of the American colonies found it increasingly difficult to avoid a critical decision. They could continue to consider themselves Englishmen, loyal to the mother country, or they could join those who saw separation from Great Britain as the only way to maintain their liberties. These decisions bitterly divided colonies, towns, and even families. Those who chose the first path were called Loyalists by their friends and Tories by their enemies. The second group called themselves Patriots, but their enemies referred to them as Rebels.

Most sources suggest that of the approximately 2.5 million people living in the American colonies at that time, 20 to 30 percent were Loyalists. Another 20 percent were enslaved Africans (few of whom were allowed to participate in this war) and another 300,000 to 400,000 did their best to remain neutral. Those supporting independence probably counted for less than half of the people of the colonies.

At the end of 1776, it was far from clear that the Patriots would succeed in achieving the independence they had claimed earlier that year. Although the British were forced out of Boston in March, the newly-formed Continental Army under Gen. George Washington lost the port of New York in the fall, barely escaping total defeat. Victories at Trenton, New Jersey, in December and Princeton, New Jersey, in January seemed to stop the downward spiral.

1777 was a critical year. The British planned a major northern campaign designed to split the rebellious colonies in two. During the summer, Gen. John Burgoyne led his army, which included thousands of professional British and German soldiers and American loyalists, down the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor toward Albany with apparent ease. In August, however, things began to go wrong for the British. American militiamen routed a British force trying to capture provisions stockpiled at Bennington, Vermont. What seemed like a small defeat here at the Battle of Bennington in New York near the border between New York and the new Republic of Vermont cost Burgoyne 10 percent of his army and critical time. In October, the British campaign ended in humiliating defeat at Saratoga in New York, when Burgoyne was forced to surrender his entire army.

Locating the Site

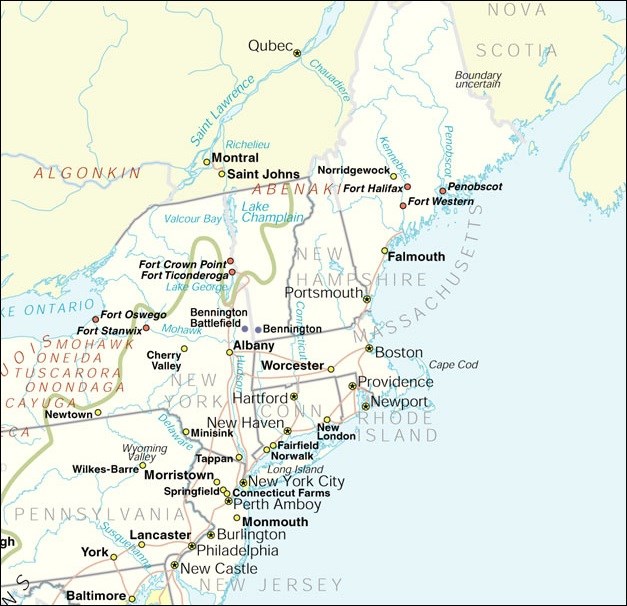

Map 1: Northeast United States.

(National Park Service)

In the 18th century, both New York (a Tory stronghold) and New Hampshire claimed the land now known as Vermont and made large grants of land there during the mid 1700s. In the 1760s, Ethan Allen, a New Hampshire landowner, using his own army called the "Green Mountain Boys," vigorously defended New Hampshire land titles against those who claimed the same lands granted by New York. The conflicting land grants were known as the "Hampshire Grants" and during the Revolution it achieved independence and became the "Republic of Vermont." Vermont remained an independent republic until 1791, at which point it joined the United States as that fledgling nation's fourteenth member.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate Vermont. What natural features form much of Vermont's borders with New York and New Hampshire? How do you think disputes over this land might have impacted residents' decisions about supporting independence for the colonies?

2. Locate the Bennington Battlefield in New York and the town of Bennington in Vermont. Based on what you have learned so far, why were British forces making their way toward Bennington, Vermont? Why do you think the battle actually took place in New York?

Locating the Site

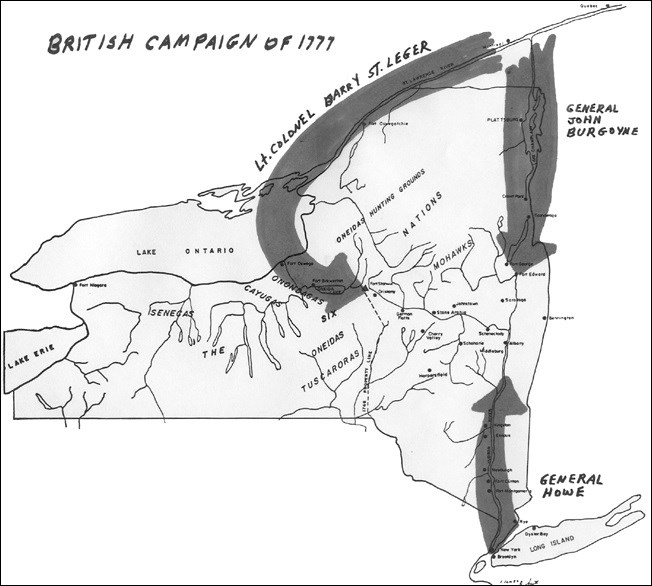

Map 2: British Northern Campaign of 1777.

In 1775, British Gen. John Burgoyne identified the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor, an historic gateway between Canada and the northern colonies of British North America, as the primary target for British military operations in North America. If the British army could control it from Canada to New York City, they could cut New England off from the rest of the colonies, secure the route for supplies and reinforcements from Canada, and strengthen Indian alliances, thereby crushing the rebellion quickly and decisively.

The plan called for a three prong attack into the heart of the colony with all three invading forces meeting in Albany. The first army, led by Gen. John Burgoyne, was to invade New York moving south from Canada through the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor to Albany. The second force, commanded by Gen. Barry St. Leger, was to move down Lake Ontario from Canada to Oswego, New York and hook eastward through the Mohawk Valley towards Albany. The third force, to be commanded by Gen. William Howe, was to move north up the Hudson River valley from New York City to Albany.

Questions for Map 2

1. Identify the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor on Maps 1 and 2. Why did Burgoyne think it was so important to control this region? What was the ultimate goal of the Northern Campaign?

2. Who were the commanders of the British forces? Where did they plan to converge?

3. Locate and identify the lakes and the rivers along Burgoyne's and St. Leger's routes. Why do you think it would have been useful for the troops to follow these bodies of water?

4. Map 2 indicates the Northern Campaign not as it was planned, but as it actually unfolded. What can you learn about the course of the campaign by carefully studying Map 2?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The British Forces

By the summer of 1777, the British were well into their third year of trying to quell the American revolutionaries. Gen. John Burgoyne and his 8,000 troops, artillery, baggage train, and supply boats had been moving south from Quebec towards Albany, New York, for three months. He had captured several American forts along the way, encountering no significant opposition. By August, however, he found himself short of provisions, wagons, cattle, and horses. Burgoyne decided to send an expeditionary force into New England under Lt. Col. Friedrich Baum, one of the German officers in his command. The goal of the expedition was to capture military supplies that were being stockpiled at Bennington (now called Old Bennington), Vermont, and to collect cattle and horses for shipment back to the main army.

Philip Skene, a prominent local Loyalist landowner, was acting as an interpreter for Baum, who spoke no English. He assured Burgoyne that he would find extensive support from residents of New York and Vermont on his march to Albany. He had good reason for his belief. New York was a Tory stronghold and many colonists living in Vermont were also ready to join the Loyalist cause. This support was important to the success of Burgoyne's campaign. The British had to carry most of what they needed with them, relying on supply trains from distant Quebec for resupply. They hoped that local supporters would provide them with fresh food, horses, and cattle.

Baum's forces included about 650 professional British and German soldiers, as many as 500 Canadian and Loyalist volunteers, and more than 100 American Indians. The Mohawks had fought with the British during the French and Indian War. They were difficult allies because they preferred to fight in their own way and at their own time. The Loyalist forces included about 300 members of the Queens Loyal Rangers, recruited by Col. John Peters of Bradford, Vermont, and several hundred local Tories. One colonist who fought with the British at Bennington recalled:

I lived not far from the western borders of Massachusetts when the war began. . . . Believing that I owed duty to my King, I became known as a loyalist, or, as they called me, a tory; and soon found my situation rather unpleasant. I therefore left home, and soon got among the British troops who were coming down with Burgoyne, to restore the country to peace, as I thought.¹

Most of the German soldiers came from the small states of Hesse and Brunswick, whose rulers rented out their armies to whoever would pay for them. Many of these "Hessians," as they were usually called, were dragoons, heavily armed men who normally fought on horseback, but were at that time in search of horses. A British eyewitness, Thomas Anburey, described their appearance as they moved towards Bennington:

The load a soldier generally carries during a campaign, consisting of a knapsack, a blanket, a haversack that contains his provisions, a canteen for water, a hatchet and a proportion of the equipage belonging to his tent, these articles (and for such a march there cannot be less than four days provisions), added to his accoutrements, arms and sixty rounds of ammunition, make an enormous bulk, weighing about sixty pounds. . . . [The dragoons] have in addition a cap with a very heavy brass front, a sword of an enormous size, a canteen that cannot hold less than a gallon, and their coats, very long skirted. Picture to yourself a man in this situation, and how extremely well calculated [he is] for a rapid march.²

As Lt. Col. Baum prepared to set off toward Bennington, Gen. Burgoyne gave him these instructions:

It is highly probable that the corps [of Green Mountain Rangers] under Mr. Warner, now supposed to be at Manchester, will retreat before you; but should they, contrary to expectations, be able to collect in great force, and post themselves advantageously, it is left to your discretion to attack them or not, always bearing in mind that your corps is too valuable to let any considerable loss be hazarded on this occasion. . . . All persons acting in committees, or any officers acting under the directions of Congress, either civil or military, are to be made prisoners.³

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why did Burgoyne send out troops to raid Bennington?

2. Who were the main groups fighting on the British side? How many men were in each group? Why were they fighting? Who were their leaders?

3. What do you think it would have been like to march on rough roads through woods carrying 60 pounds of equipment? In what ways would it have been even more difficult for the dragoons?

4. Based on Lt. Col. Baum's orders, what sort of opinion did Gen. Burgoyne have of American soldiers?

Reading 1 was compiled from Richard Greenwood, "Battle of Bennington" (Rensselaer County, New York) National Historic Landmark documentation, Washington, D.C.: U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975 and Philip Lord, Jr., compiler, War Over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement Patterns on the Bennington Battlefield--1777 (Albany: The State Education Department, 1989).

¹Philip Lord, Jr., compiler, War Over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement Patterns on the Bennington Battlefield--1777 (Albany: The State Education Department, 1989), 54.

²Philip Lord, Jr., War Over Walloomscoick, 99.

³Richard Greenwood, "Battle of Bennington" (Rensselaer County, New York) National Historic Landmark documentation, Washington, D.C.: U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The Americans

Most of the residents in New Hampshire supported independence, though for the men of the Hampshire Grants independence from New York was often at least as important as independence from Great Britain. The farmers from the Grants were among the first to rally to the call to arms when hostilities between the British and the colonists erupted at Concord and Lexington. In 1775, a year before the Declaration of Independence was signed, Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys joined Benedict Arnold and Patriots from Massachusetts in a successful attack on the British at Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. By June 1777, the newly declared state of Vermont was preparing to select delegates to the Continental Congress. When Burgoyne captured Ticonderoga in July, Vermont appealed to New Hampshire for assistance in stopping the British invasion. John Langdon, presiding officer of the legislature and a rich man, offered critical help:

I have $3000 in hard money; my plate I will pledge for as much more. I have seventy hogsheads of Tobago rum, which shall be sold for the most they will bring. These are at the service of the State. If we succeed, I shall be remunerated; if not, they will be of no use to me. We can raise a brigade; and our friend Stark who so nobly sustained the honor of our arms at Bunker's hill may safely be entrusted with the command, and we will check Burgoyne. ¹

Lt. Gen. John Stark had fought with the Continental Army at Bunker Hill, in Canada, and at the Battle of Trenton, but resigned when he was passed over for promotion. He agreed to take command of the New Hampshire militia on condition that he operate independently, outside the authority of the Continental Congress. Within six days, almost 1500 men signed up. Stark was difficult, but his experience was needed.

At Bennington, Stark commanded approximately 2,200 militiamen who had assembled to oppose Burgoyne's advance. Some 1400 came from New Hampshire, 600 from Vermont, about 40 from New York, and the balance came from Massachusetts and Connecticut. The volunteers were mostly farmers and townspeople. There was no time for lengthy training and no money for uniforms or expensive weapons. The volunteers left their businesses or farms wearing their usual clothes and often carrying their own guns. A British soldier captured at Bennington described the appearance of the colonial militia:

Each had a wooden flask of rum hung on his neck. They were all in bare shirts, had nothing on their bodies but a shirt, vest, long linen trousers which extended to the shoe, no stockings--powder horn, bullet bag, rum flask, and musket.²

The volunteers were unpracticed in military discipline, but Stark knew how to lead them. When the Battle of Bennington began, he calmed his nervous soldiers, facing cannon for the first time, by joking that: "The rascals know I'm an officer; they're firing a salute in my honor." Later, as the battle rose in fury, he is supposed to have told his troops: "There stand the redcoats; today they are ours, or Molly Stark sleeps this night a widow."³

Questions for Reading 2

1. What is meant when it says, "for the men of the Hampshire Grants independence from New York was often at least as important as independence from Great Britain?" If needed, refer to Reading 1.

2. Who were the main groups fighting on the American side? How many men were in each group? Why were they fighting? Who were their leaders? Make a chart comparing the information about American forces to the information presented in Reading 1 about the British forces. Based on this information, which group do you think was better prepared for battle? Explain your answer.

3. Why do you think John Langdon offered to give up so much of his fortune for the Rebel cause? Can you figure out what "plate" is? What do you think he meant when he said his plate would "be of no use to me" if they failed?

4. What qualities made John Stark a good choice to lead the American troops at the Battle of Bennington?

Reading 2 was compiled from Richard Greenwood, "Bennington Battlefield" (Rensselaer County, New York) National Historic Landmark documentation, Washington, D.C.: U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975 and from Philip Lord, Jr., compiler, War Over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement Patterns on the Bennington Battlefield-1777 (Albany: The State Education Department, 1989).

¹"Souvenir Program: One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Bennington" (Wallomsac, NY: State of New York Cooperating with the State of Vermont, 1927), 7.

²Philip Lord, Jr., compiler, War Over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement Patterns on the Bennington Battlefield--1777 (Albany: The State Education Department, 1989), 67.

³Earle Williams Newton, "Green Mountain Rebels," Vermont Life, Vol. III, No. 1 (1948), 36.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Battle of Bennington

Lt. Col. Friedrich Baum set out on August 11th. The heavily loaded German troops, slow moving under the best of circumstances, plodded towards Bennington. On August 14th, Baum encountered an American scouting party at the Sancoick Mill--about eight miles west of Bennington. His report early that day to Burgoyne was confident:

Sancoick, Aug. 14, 1777, 9 o'clock

Sir: I have the honor to inform your Excellency that I arrived here at eight in the morning, having had intelligence of a party of the enemy being in possession of a mill, which they abandoned at our approach, but in their usual way fired from the bushes, and took the road to Bennington. . . . They left in the mill about seventy-eight barrels of very fine flour, one thousand bushels of wheat, twenty barrels of salt, and about one thousand pounds' worth of pearl and potashes. . . . By five prisoners here they agree that fifteen to eighteen hundred men are in Bennington, but are supposed to leave it on our approach. I will proceed so far today as to fall on the enemy tomorrow early, and make such disposition as I think necessary from the intelligence I may receive. People are flocking in hourly and want to be armed. The savages cannot be controlled; they ruin and take everything they please.

I am, etc. F. Baum

P.S. Beg your excellency to pardon the hurry of this letter, it is written on the head of a barrel.¹

The scouts headed back with news of Baum's approach. Far from retreating, Stark immediately advanced to meet the Germans as they moved towards Bennington. Although Baum had little respect for the fighting ability of Stark's poorly trained and poorly equipped backwoodsmen, he realized he was outnumbered and sent for reinforcements. By the close of the day on August 14, the American and British forces were at a standoff about four miles east of Sancoick. Stark's advantage of superior numbers was offset by Baum's strong position on a high elevation with professional troops supported by cannons and protected by earthen fortifications.

The steamy summer heat produced heavy rains throughout the next day. Both armies waited for the rain to stop, contemplating their strategies. Baum spent the day improving and expanding his position on "Hessian Hill," and posting a small force of Loyalists on a lower hill across the river, later known as the "Tory Fort." At dawn Burgoyne had sent about 500 German troops under Col. Breymann to reinforce Baum, but the heavily burdened army made little progress over the rain-sodden roads.

On the 16th, the weather cleared. Stark set in motion an elaborate plan to dislodge the British:

I divided my army into three Divisions, and sent Col. Nichols with 250 men on their rear of their left wing; Col. Hendrick in the Rear of their right, with 300 men, order'd when join'd to attack the same. In the mean time I sent 300 men to oppose the Enemy's front, to draw their attention that way; Soon after I detach'd the Colonels Hubbert & Stickney on their right wing with 200 men to attack that part, all which plans had their desired effect.²

At three o'clock in the afternoon, the colonial militias that had gradually surrounded the British position attacked from all sides.

By five o'clock, the British were routed. A German observer described the fight on Hessian Hill:

Our Dragoons fired at the enemy with cool deliberation and much courage but it did not last long. They loaded their carbines behind the breastworks but, as soon as they raised up to aim their weapons, a bullet went through their heads, they fell backwards and no longer moved a finger. Thus in a short time our largest and best Dragoons were sent to eternity.³

Their ammunition exhausted, the remaining Germans were overrun, and the fleeing survivors were pursued down the wooded slopes to be captured or killed. Baum himself was mortally wounded. The Indians escaped early in the fighting and slipped away to the west to rejoin Burgoyne's main force.

The Patriots also drove the Loyalists from their hill, picking off the fleeing Tories as they attempted to escape across the river. Col. Peters described the fierce action there:

The Rebels pushed with a Strong party on the Front of the Loyalists where I commanded. As they were coming up, I observed A Man fire at me, and I returned, he loaded again as he came up & discharged again at me, and crying out Peters you Damned Tory I have at you, he rushed on me with his Bayonet, which entered just below my left Breast, but was turned by the Bone. By this time I was loaded, and I saw that it was a Rebel Captain, an Old School fellow & Playmate, and a Couzin of my wife's: Tho his Bayonet was in my Body, I felt regret at being obliged to destroy him. 4

The colonial troops had suffered few losses, but were widely dispersed--looting, guarding prisoners, and pursuing the retreating survivors. At this point, Breymann's reinforcements, ignorant of Baum's disaster, finally arrived. Col. Stark described the contest that saved his victory from reversal:

Luckily for us Col. Warner's Regiment [of Green Mountain Rangers] came up, which put a stop to their career. We soon rallied, & in a few minutes the action became very warm & desperate, which lasted till night; we used their own cannon against them, which prov'd of great service to us. At Sunset we obliged them to retreat a second time; we pursued them till dark, when I was obliged to halt for fear of killing my own men.5

The end of the day on August 16 found the British foraging force virtually annihilated and Burgoyne in a more dangerous position than before. His army had lost approximately 10 percent of its men and was still short of supplies. The defeat at Bennington greatly discouraged Burgoyne's uneasy Indian allies. For the Patriots it was a great psychological victory, bringing in hundreds of new militia enlistments. Three months later, on October 17, Gen. Burgoyne surrendered his entire army following his humiliating defeat at the decisive Battle of Saratoga. By the terms of the Convention of Saratoga, Burgoyne's depleted army, some 6,000 men, marched out of its camp "with the Honors of War" and stacked its weapons along the west bank of the Hudson River. Many historians believe that the outcome of that battle might have been different if Burgoyne had gathered the support that he expected from Baum's expedition to Bennington, making it possible for the British to engage the Americans before they could collect enough men to oppose them.

Questions for Reading 3

1. What do you think Baum meant by describing the enemy firing "in their usual way"?

2. What intelligence did Baum learn from prisoners?

3. Why might people have been "flocking in hourly"?

4. Based on Peters' recollection, how did the Loyalists and the Patriots feel about each other?

5. What effect did the Battle of Bennington have on the Patriots? On the British?

6. What support had Burgoyne expected from Baum's expedition to Bennington? How might it have changed the outcome of the battle? If needed, refer to Reading 1.

Reading 3 was compiled from Philip Lord, Jr., compiler, War Over Walloomscoick: Land Use and Settlement Patterns on the Bennington Battlefield-1777 (Albany: The State Education Department, 1989) and from Richard Greenwood, "Battle of Bennington" (Rensselaer County, New York) National Historic Landmark documentation, Washington, D.C.: U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1975.

¹Translated from the German. As cited in Philip Lord, Jr., War Over Walloomscoick, 7.

²"Souvenir Program: One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Bennington," 17.

³Julius Friedrich Wasmus, "Journal," manuscript translated by Lion Miles and Helga Doblin, n.p.; cited in War Over Walloomscoick, 68, note.

4 "A Narrative of John Peters, Lieutenant Colonel of the Queens Loyal Rangers;" cited in War over Walloomscoick, 58.

5"Souvenir Program of the Battle of Bennington," 18.

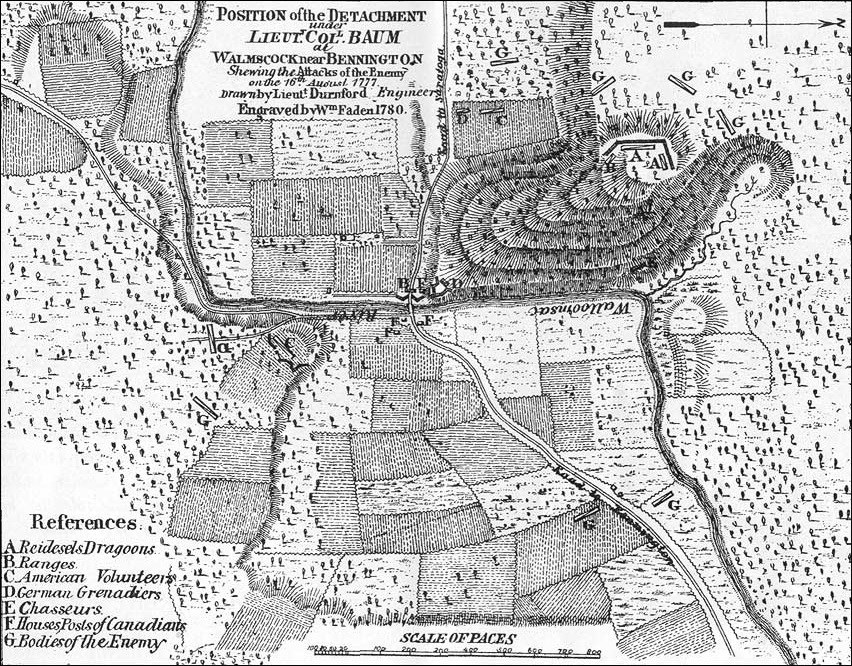

Visual Evidence

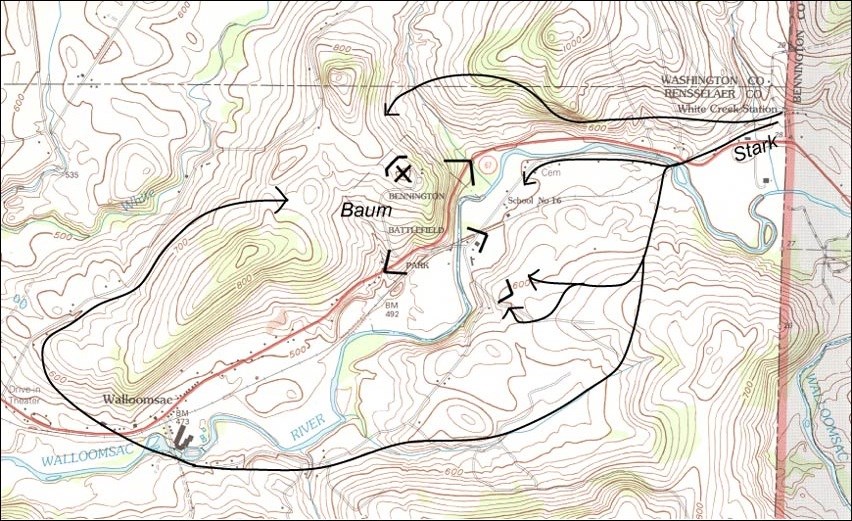

Illustration 1: Site of the Battle of Bennington.

Illustration 1 was drawn in 1777 by Lt. Desmaretz Durnford, an engineer with the British army at the Battle of Bennington. It was later engraved and presented to the British Parliament in 1780 as part of General Burgoyne's explanation of the failure of his campaign. Unlike most modern maps, north is to the right, rather than at the top.

Questions for Illustration 1

1. Find the Walloomsack River. What other natural features can you identify? What man-made elements can you locate?

2. Changes in elevation are indicated by a kind of shading known as "hachuring," short lines beginning at the top of a slope and ending at the bottom. Based on this, where is the highest part of the site? According to the key, who occupied the hill when the battle began?

3. Trees indicate woods, while the roughly rectangular areas along the river represent fields. Based on Illustration 1, how would you describe the landscape where the battle took place?

4. If you were commanding an army and looking for a good place to establish your camp, where might you have put it? Why?

Visual Evidence

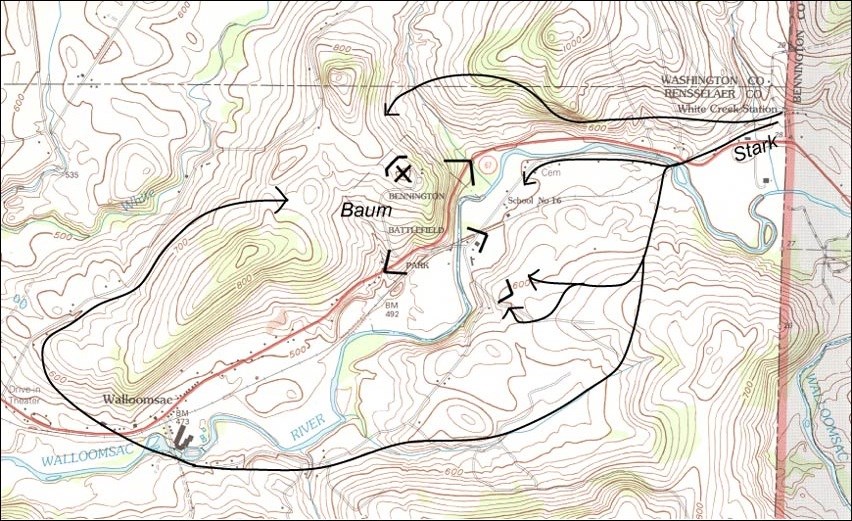

Illustration 2: The British position and the

American attack.

These modern maps use contour lines to show topography. Each line represents a specific elevation above sea level. When contour lines are close together, they show steep slopes. Widely spaced contour lines show flat lands.

The lines with arrows represent Stark's troop movements. The "v" marks indicate the locations of Baum's forces.

Questions for Illustration 2

1. Compare Illustration 2 with Illustration 1. Remember that north is at the top of this illustration and at the right side of the Durnford illustration. What features that you identified on Illustration 1 can you find on Illustration 2?

2. Illustration 2 shows the location of Baum's forces on the morning of August 16. The "v" marks show where defensive walls of earth and logs were built to protect the main hilltop camp, the baggage train and the bridge over the river. Can you find Hessian Hill where the Reidesels Dragoons were located? Can you identify the Tory Fort across the river where the American Volunteers were located? If needed, refer to Illustration 1.

3. How is Baum's position shown in the Illustration 1 drawn by Durnford? Which map is easier to understand?

4. Illustration 2 also shows how General Stark divided his forces to surround the British position. How many units attacked? Each unit was supposed to attack at the same time. How would you ensure that these attacks were coordinated? What do you think might have happened if they had not occurred simultaneously?

5. Compare Illustration 2 with Reading 3. Which gives you a better understanding of what happened at the battle?

Putting It All Together

Many different groups fought at the Battle of Bennington, for many different reasons. By their actions, in this tiny valley near the frontier in northern New York, they helped determine whether the American colonies would become an independent nation. The following activities will help students evaluate factors contributing to the outcome of the battle, understand historical documents, and learn about significant events in their community.

Activity 1: The People, the Cause, the Land, the Strategy

Now that students have learned the outcome of the Battle of Bennington, ask them to write a brief evaluation of the people involved, their behaviors, and the impact. Then divide the class into four groups. Assign each group one factor that helped determine the outcome of the battle: the people and their leadership, their motivation for fighting, the physical characteristics of the site, or the strategies used. Hold a debate, with each group using evidence from the lesson to build a case for their particular factor being the one that won the battle. Have the class vote to determine the most convincing presentation.

Activity 2: Historical Language and Images

Historical documents often contain unfamiliar language. In some instances, it may be essential for understanding to stop and research the exact meaning of a word. Ask students to make a list of unfamiliar expressions in this lesson. For example, in Reading 2, John Langdon mentions "plate." Did students know what that was? Were they able to get an idea from the context and continue reading? Make a list of expressions the students did not understand. Assign different students a word or group of words to research. Then have them complete the list on the board by writing in the definitions of the unfamiliar words. Discuss with the class whether knowing exactly what a historical document meant made a difference in their understanding the document.

Activity 3: Moments of Heroism

Ask students to survey older members of the community to identify events in the community's past that filled residents with pride. What were the issues? Who participated? Were the events controversial or combative? How were the issues decided? Is there any public recognition of the events--monuments, public sculptures, or paintings in a public building? Ask students to make a rough sketch that reflects a particular event and write a short narrative to accompany the sketch. Students should decide if their sketch and description is intended to be historically accurate, or used to depict the emotional significance of the event to the community--a moment of heroism for example. Drawings could be displayed as an "art gallery" of community history.

The Battle of Bennington: An American Victory--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at The Battle of Bennington: An American Victory, students learn about some of the many groups that fought on both sides of the American Revolution. They also come to appreciate that the Revolution was not just a contest between American Patriots and British soldiers, but, in some places, a bitter civil war. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Lighting Freedom's Flame

The National Park Service created a Web page celebrating the 225th Anniversary of the American Revolution. The site includes a Revolutionary War timeline, information on units of the National Park Service related to the Revolutionary War, a bibliography showing highlights from the vast literature on the Revolution, and links to many related sites.

Saratoga National Historical Park

Saratoga National Historical Park is a unit of the National Park System. Visit the park's web page to find information on the decisive battle that took place three months after the Battle of Bennington. Burgoyne's surrender after his defeat here marked a turning point in the Revolution.

Fort Stanwix National Monument

Fort Stanwix National Monument is a unit of the National Park System. The park's web page includes a travel guide to the Oriskany Battlefield. This battle also contributed to the failure of Burgoyne's Campaign to divide the Colonies.

Liberty!

The Public Broadcasting Service program Liberty! has a web page for information on colonial life, international connections, and the military experience. It also includes "The Road to Revolution," an interactive game in which a virtual colonist moves through most of the major battles of the Revolution, including Saratoga.

Library of Congress

Search the American Memory Collection for primary written and visual documents relating to the Revolutionary War, including early printed versions of the Declaration of Independence.

U. S. Army Center of Military History

The Historical Resources Branch Web page contains bibliographies on specialized topics related to the conduct of the war, including material on Loyalists and on the Germans.

Tags

- battle of bennington

- american revolution

- new england

- new england history

- battle

- new york

- new york history

- colonial america

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- vermont

- vermont history

- military wartime history

- colonial

- 250

- american independence

- america 250 nps

- military history

- twhplp

- america 250