Just north of the White House lies a seven-acre patch of land that has undergone many transformations. It has been a race track, a grave yard, a zoo, and briefly—during the War of 1812—a military encampment for American soldiers. Today, Lafayette Square boasts manicured lawns and imposing monuments commemorating President Andrew Jackson and foreign heroes of the American Revolution. When President Thomas Jefferson designated the park as public land in 1804, he created a symbolic space where all Americans could have access to the home of the sitting president. Since then, Americans have gathered here to raise their voices in celebration and in protest. Alice Paul and members of the National Woman’s Party stood vigil here during the winter of 1917 to demand women’s suffrage. Civil rights and student activists protested racial injustice, nuclear proliferation, and the Vietnam War.

Places like this small park are important parts of the United States’ political landscape. While locations like Philadelphia’s Independence Hall and Virginia’s Appomattox Court House have been the sites of watershed moments in our country’s political development, American politics were never confined within their walls. Less exalted spaces—community parks, taverns, street corners, and workshop floors—have also stood witness to the evolving relationships between American citizens and the political process. Everyday people shape this political landscape as much as presidencies and governmental institutions. Many of their stories are preserved and interpreted in our national parks and historic sites.

For the diverse peoples who have lived in North America, political life frequently revolves around simple but incredibly powerful ideas. Liberty—the state of being free from oppressive restrictions imposed on one's way of life, behavior, or political views—has been one of the most enduring and powerful concepts in American politics. It is embedded in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States as an inalienable right. It has sparked revolutions, built institutions, and fueled social movements. To understand the contentious past of American politics, it is useful to understand liberty as a living, evolving idea. Its features shift depending on who defines it and who has access to it. Evolving conversations about liberty and freedom has been one of the most important factors that have shaped American political culture.

Steamtown NHS

In many ways, the American Revolution provided a radical extension of rights and freedoms to people living in the new nation. Reform measures such as open legislative assemblies and reduced property requirements for voting and holding office created opportunities that had once been unavailable to artisans, farmers, and unskilled laborers. But there were still barriers to full political participation. In early America, an American’s ability to freely participate in political life was profoundly shaped by their race, gender, and economic status. The legal tradition of “femme covert” categorized women as legal wards of their fathers and husbands and failed to recognize them as independent political actors. Free and enslaved black Americans were not granted citizenship, the right to vote, or the ability to give testimony in a court of law. Indigenous peoples faced similar legal restrictions and would not receive U.S. citizenship until 1924. Many Americans would spend centuries fighting to overcome these barriers in order to become full participants in American civic culture.

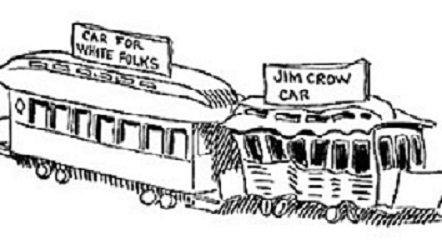

One of the greatest attempts to extend full equality to marginalized groups took place nearly a century later. During Reconstruction (1865-1877), the federal government attempted to enforce a series of legal reforms that would reunite a nation torn apart by civil war and also redefine American citizenship. The 14th and 15th Amendments extended U.S. citizenship and voting rights to newly emancipated black men. Black men voted in elections and held political office. Black communities built schools, churches, and other organizations throughout the South. Many of these advancements were short-lived. By the late 1800s, white supremacist groups used violence and terror to keep black Americans from the polls. Black codes and Jim Crow laws erected new legal barriers to overcome. Despite the dangers these posed to their lives and livelihoods, black Americans continued to fight for full racial equality.

Other Americans hoped that the abolition of slavery signaled an opportunity for women to also claim greater freedom and equality. Women’s rights groups such as the National American Woman Association called for female suffrage, more liberal divorce laws, and broad legal and economic equality for women. But the laws that protected racial equality failed to ensure gender equality—the 14th Amendment only protected the voting rights of men and the 15th Amendment outlawed voting restrictions based on race but not gender. It would take decades of legal struggles, political activism, and open defiance of gender inequality before women would win the vote with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

Voting isn’t the only way that Americans have made their voices heard in the political landscape. During the 1800s, laborers across the nation organized in unprecedented numbers to demand fair wages and better working conditions. While middle-class social reformers tried to address the socials ills of modern society, American workers envisioned alternative political systems that would eliminate inequality. They read the work of Karl Marx and Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, a novel that described American in the year 2000 as a capitalistic utopia. Protestant ministers preached The Social Gospel to address poverty and the deplorable living conditions of the urban poor. As labor unrest continued into the 1900s, organizations such as the Knights of Labor, the American Federation of Labor, and the International Workers of the World (IWW) swelled. In the 1912 presidential election, Eugene V. Debs earned nearly 6 per cent of the popular vote as the Socialist Party candidate. Similar strains of radicalism would permeate American politics through the remainder of the century.

As many Americans envisioned a future society free of inequality and exploitation, their ideas often had little room for the millions of immigrants arriving on the United States’ shores. During the 1890s, millions of immigrants arrived from southern and eastern Europe and across the Asian continent. This signaled a shift in the United States’ immigrant population, which traditionally hailed from western European countries. Social Darwinism—a term coined to describe the idea that different populations evolve at different rates and applied the concepts of “natural selection” and “survival of the fittest” to contemporary society—categorized these new immigrant groups as distinct and allegedly inferior “races” that were poorly-suited for American democracy. Racist immigration laws such as the 1875 Page Act and the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act used pseudo-science to justify the exclusion of Chinese immigrants, who supposedly posed health and moral threats to “white” U.S. citizens. Such laws reinforced the belief that freedom and political participation was not an inherent right of all people living in the United States, but was a privilege for particular “worthy” groups.

The United States’ position abroad also experienced a rapid transformation during this period. The country emerged from the wars of 1898 an undeniable imperial power with new territorial acquisitions including Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. During World War I, Woodrow Wilson promoted the idea of “liberal internationalism” which merged the United States’ desire to spread democracy abroad with an increased willingness to intervene in foreign conflicts. This new approach to foreign policy would play a role in the United States’ participation in World War II and its emergence as a global superpower.

These developments abroad, paired with the influx of immigrant populations with international ties, it soon became evident that the shape of the country’s political landscape extended far beyond its national borders. This was particularly true for the decades after World War II, when the United States’ political and economic stand-still with the Soviet Union so profoundly shaped its domestic and foreign policies. During the Cold War, the struggle to contain communism at home and abroad touched the lives of all U.S. citizens. Abroad, many fought drawn-out wars in Korea and Vietnam and participated in covert operations throughout South America, Africa, and the Middle East. At home, even more U.S. civilians sought to thwart communist spies and other politically subversive groups.

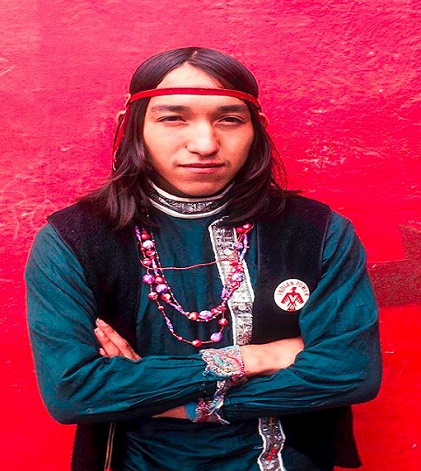

Anticommunism in the United States created an atmosphere of fear that created immense challenges for many U.S. citizens advocating for equal rights. While many Americans saw the civil rights marches, sit-ins for racial integration, and anti-war demonstrations of the 1950s through the 1970s as new innovations of radical, socialist politics, they were—in reality—the culmination of decades of organizing and advocating for full political, social, and economic equality. The political movements of this period definitively shifted conversations about what American society looked like. If in the past Americans believed national identity was acquired by social or racial assimilation, then by the 1960s more and more Americans celebrated their country’s diverse, multicultural populations. While activist within the Black Freedom Movement, the American Indian Movement, or the Gay Liberation Front addressed the specific desires of their communities, each articulated a desire for liberty so fundamental to American political life.

As it adopts new strategies to protect freedom and fight terrorism at home and abroad, the United States finds itself confronting many of the same debates it faced since the first years of the Early Republic—Who are entitled to the freedoms promised in its founding documents? To what extent are Americans willing to suspend civil liberties to ensure those freedoms? And, how will our country preserve its greatest ideals in a complex and evolving world?

Visit the National Park Service Telling All Americans' Stories portal to learn more about American heritage themes and histories.

Last updated: February 9, 2017