Last updated: March 24, 2023

Article

Tales of a Silver Ghost: Alice Longfellow's Rolls-Royce

In July 1913, the year before the First World War began, Alice Mary Longfellow was in the middle of a two-year European tour. Chauffeured by her driver Walter Critchell, and accompanied by her maid Sarah, she would soon be joined by her niece Erica “Bunny” Thorp. The group was traveling in style in Alice’s Pierce Arrow, but Alice was not content. Thinking she might prefer a Rolls-Royce she began making inquiries.

Those inquiries resulted in Alice’s purchase of a Rolls-Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost, which is documented in roughly 40 letters from the Rolls-Royce Company to Alice. These give insight into Alice’s questions and choices, and allow us to reconstruct her purchase. Letters to her family document Alice’s pleasure in the new car and recount an unexpected and chaotic departure from France in August 1914.

Alice Mary Longfellow Papers, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS

Purchase

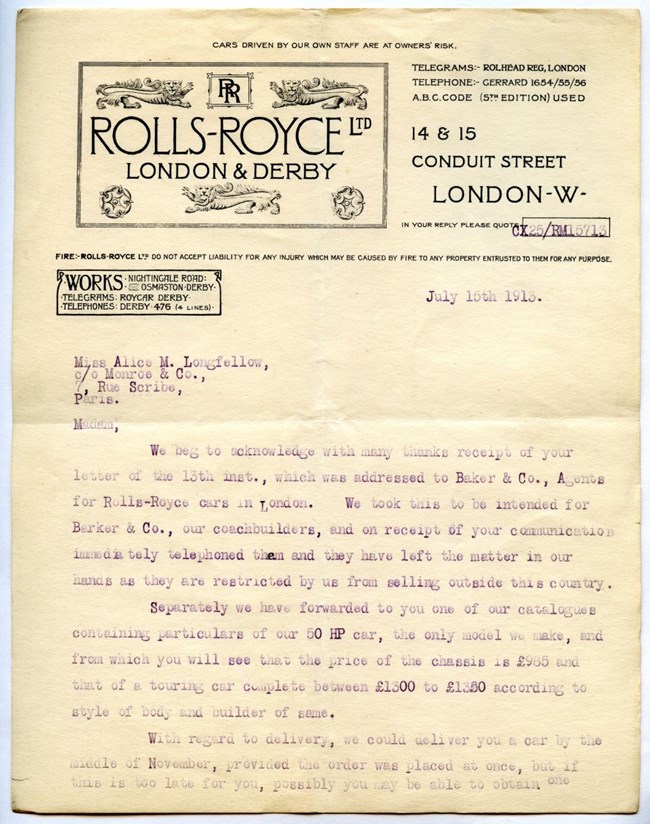

We note you have been using up to the present a Pierce Arrow car which we also understood was the best car in America…. Perhaps the very best reason why people should believe that the Rolls Royce is better than the Pierce Arrow is because the Pierce Arrow Company admit this themselves.

Thus wrote Mr. L. W. Cose from his London office to Alice in Paris in July 1913. The chassis would cost £985, a complete touring car between £1300 to £1350 depending on the appointments. If ordered immediately, Alice could expect delivery by the middle of November.

Alice wanted comfort and style but had questions. In answer Mr. Cose wrote in early August:

We enclose herewith two small cuttings of leather of light brown shades and shall be glad to know if either of these appeal to you: if not, we shall endeavor to obtain some other shades for you. These are the two usually adopted.

We are very anxious to have the front seat, which we note you mostly use when touring, as comfortable as possible for you, and if you can give us any special instructions as regards height, slope and depth of the seat, we shall be glad to make a point of attending to this for you.

With regard to the wire wheels, we have never yet heard anyone speak of them as being the cause of a side sway…We feel certain that the wheels are not affected by extremes of heat and cold, and we should think you would be perfectly safe in adopting wire wheels for your car, in fact, a large number of our cars are now so fitted.

In Paris Alice had not tried an “open car”, but Critchell, in England to learn more about the Rolls-Royce had. “We took your chauffeur”, Cose wrote, “down to Messrs. Barkers’ [the coachbuilder] in one of the latest Rolls-Royce which seemed to impress him very much.” Apparently eager to buy the car, Alice signed a contract for purchase on August 18th sending it along with her deposit of £328.6.8 to Rolls-Royce.

Alice agreed to the proposed chassis, a “colonial type” providing “increased ground clearance and…better suited for use in America” but differed with Rolls-Royce on the type of steering column, acceding to their recommendation only after much persuasion. There was discussion about where to install the spare tyre and she made a request to install a brass rail for rugs “to be fitted behind the driver’s seat.” Despite their assurances about wire wheels, Alice opted for wood.

Continuing to fine-tune her wishes after her initial payment, Alice changed her mind about the car’s color. “We understand…you have now decided not to have the car painted blue, “wrote Sales Manager Mr. Wm. Cowen, “will you kindly let us know whether the instructions already given concerning the upholstery still hold good…” Alice’s long-distance decision-making may have caused a few headaches on both sides of the Channel.

Delivery

Once in production attention was turned to delivery. Estimated charges from London to Genoa were £61 for packing, freight and insurance. Passage would take about one month. If she paid more Alice could have the car sooner. She decided on the fastest delivery, Grande Vitesse—railroad—overseen by American Express Co. with delivery to Florence.

Shipment was delayed and Alice questioned why. Both sides were responsible. Alice had not yet made her final payment and there was a mistake in production. Instead of a “front seat with a high division” Messrs. Barker had installed “semi-bucket” front seats.” The car was recalled for correction. On November 26th Cowen assured Alice “Immediately we obtained the car from Messrs. Barker, it was handed to the packers and by the time they had packed it, we had received your remittance, so that really no delay was caused by our waiting for the money.” He continued “At the same time, we beg to explain to you that when you were good enough to place the order with us, you kindly undertook on the order-form which you signed, to pay the balance on receipt of advice from us that the car was ready for delivery.”

Arrival

From late November through early December a flurry of letters cover a variety of administrative details, while also expressing Rolls-Royce’s hopes that Alice had received the car. It was not until December 23rd that Cowen could finally affirm “we are very pleased to hear the car arrived safely.”

On “Thanksgiving Day” Alice wrote to her sister Edith, “The new car, Rolls-Royce runs like a dream so far as noise, with a long flexible spring that rides the roughnesses like a canoe—.”Alice’s niece Erica, who had joined the entourage in August also wrote home December 5th, “Hooray, the car has come! Miracle of miracles and we are celebrating most joyously tonight!”

In February 1914 Alice wrote to her brother-in-law Richard Henry Dana III, “I am sending home my old …[automobile] as I cannot sell it here…. My English car is deliciously smooth & quiet, & I enjoy it so much that it is sad to have only these rough roads, & the streets of Rome seem wilder than ever, a perfect chaos of disorder.”

Alice also expressed her pleasure to Rolls-Royce—as well as voicing complaints. Too much grease had been applied to the brass-work, marring the seat cover. The height of the hood seemed too low. The windshield needed adjustment. Alice wished to exchange the brass lamps she ordered for lamps that were black. The overall finish of the car seemed uneven. Cowen conveyed regret and addressed each comment in turn: the excess grease was an anomaly—hers was the first complaint the Company had ever received—but the seat cover would be replaced; the hood was made to spec, but for a charge it could be altered; the windshield adjustment could be made in England; a price list for new lamps was enclosed; and Cowen “carefully noted” Alice’s remarks about the finish stating it was “not in any way exceptional.”

With the New Year these concerns may have become less pressing for in January, Critchell was involved in a minor automobile accident in Italy, resulting in criminal charges and a disagreement with the insurance company about payment.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Family Papers, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS

War

Critchell was cleared in May, and in June Alice left Rome to travel through Austria, Switzerland, and Germany. Her letters to Edith charting her travels were part travelogue, part family conversation, and at times referenced the rising tensions in Europe. Alice and Erica planned to rejoin in France in July and from there depart for America on August 18th. Germany’s August 3rd declaration of war on France forced a reassessment of their plans.

From Paris on August 3, 1914, Erica wrote,

Dearest Papa,

I trust that by this time some cablegram will have reached you assuring you of our security in Paris. We won’t be able to decide definitely till tomorrow whether we shall stay or go, but everything seems to point to staying—in fact, I don’t see how we can do anything else….

Two days later Erica wrote again,

Paris, le 5 August 1914

Dearest Family,

…There has been no change in our plans, in spite of the rapid developments of the war.

The trains are as packed as ever, & the uncertainty of channel boats as great. We still have the car, tho’ I think it must be almost the only private one in Paris unrequisitioned. Being an English car registered in England & an extremely complicated one to run has saved it....

On August 8, 1914 Alice wrote from Havre,

My dear Edith,

We are living in wonderful times, making history a mile a minute, & though it is full of perplexities I wouldn’t have missed it on any account…. we drove quietly out of Paris…and the next day the French mobilized & in a few days thousands were on the frontier, so quickly & quietly, it was a marvel… It was so sudden no one was prepared, nor knew what to do….

… We had to leave all our trunks in the hotel…We brought baskets to put in the auto, & started yesterday morning in a pouring rain, & rough slippery roads for Rouen. We had to stop sixteen times to show our “laissez passer”, & the soldiers were always most polite in fact I can’t praise the French officials enough….

…The enthusiasm is quiet, but very deep. We flew the English flag at the peak, and the French behind, and had rounds of applause as we passed through the troops on the road—

On “Monday,” Erica wrote from The Royal Hotel, Winchester,

Dearest People,

Safe in England at last! ---- We can scarcely believe it & seem to have dropped into another planet in this peaceful, sunny, calm place –…

It came as suddenly as all the events of this last unforgettable week. Aunt A. & I were reading on the beach at Havre having made up our minds to stay there a week at last after hearing that no foreigners could land till after the transportation of British troops – when up dashed Critchell saying that he’d just heard that the night boat would take Americans & also the car! So we dashed madly about…& got a whole new set of passports with more minute descriptions than ever & permits to leave France & enter England & made for the boat with all haste…

Alice and Erica departed England on August 24th and traveled to New York in the Saxonia, arriving safely in September 1914, while the Silver Ghost remained in England several more months undergoing repair, tune-up, and the changes Alice requested. Critchell stayed behind with the car, leaving England in September. The car was shipped back later that year.

Christine Wirth

Epilogue

Alice kept the Silver Ghost until her death in 1928, when it was purchased from her estate. It was sold in 1930 to Alan Bemis, an antique car enthusiast who used it for commuting and long-distance trips, including hauling weather observation equipment up Mt. Washington. In 1938 the car was heavily damaged in a hurricane and over the next 51 years Mr. Bemis lovingly restored it. In 1989 he donated the auto to the Owls Head Transportation Museum in Maine, where it resides today.

In 2015 the author of this article had the unexpected pleasure of an excursion in the car. It was remarkable to think of the auto's long history, and while navigating bumpy coastal roads it was also clear that even at 102 years this well-worn Rolls-Royce remained a real joy, still riding the roughnesses “like a canoe—.”

Notes

Research for this article drew from three major sources in the Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS archives. Major sources include:

- Rolls-Royce correspondence in Series 1. Personal Materials, Alice Mary Longfellow Papers, LONG 16173.

- Alice Longfellow to Edith Longfellow Dana correspondence from July and August 1914 in Series 2. Correspondence, Alice Mary Longfellow Papers, LONG 16173.

- Erica Thorp [de Berry] correspondence to her family from July and August 1914 in the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Family Papers, LONG 27930.