In the march to war, the Republican administration worried about political resistance in Federalist New England. Madison saw “intrigue” and “seditious opposition” in those who “clogged the wheels of war.” He could not rely on Federalist-dominated states to provide able-bodied men for military service.

"Madison may have been less “rampant” than the “noisy politicians” who urged war; but after the fighting commenced, he proved himself “less crouching under difficulties” than most of these verbally energetic men." Edward Coles, private secretary to James Madison

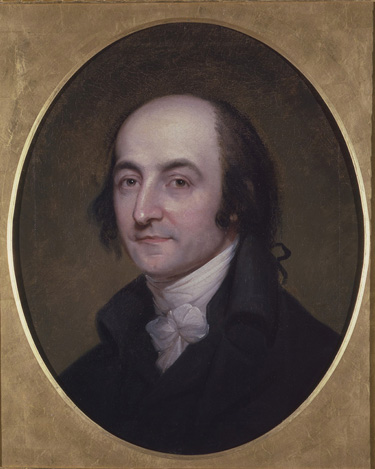

Albert Gallatin and the Federalists

NPS

In Swiss-born Pennsylvanian Albert Gallatin, Madison had a very dependable and highly competent advisor. He had initially wanted Gallatin for secretary of state, but his foreign birth and French accent had, since the early 1790s, provoked a backlash from Federalists, who regarded Gallatin as insufficiently American. Now, twenty years later, he still made the Federalists uncomfortable, and so, rather than add to the already poisoned political atmosphere, the president retained Gallatin in the same cabinet office he had held under Jefferson: Secretary of the Treasury. The man he appointed secretary of state, Robert Smith of Maryland, was a Princetonian like himself, but one who hated Gallatin and, as things turned out, felt no loyalty to Madison either. For as long as Smith remained at State, the president would be poorly served.

Madison had been the dominant voice in Congress in the formative decade of the 1790s, and a virtual “co-president” with Jefferson from 1801 to 1809. But in his own first term, he presided over a fractious cabinet. Smith was eventually replaced by James Monroe, who was not just an old friend and a former diplomat (to both England and France), but also an officer during the American Revolution who still aspired to ride at the head of an army. With Gallatin and Monroe at his side after the war began in earnest, Madison would be hearing from experienced and politically savvy men whom he knew he could trust.

James Madison and the Republicans

Watercolor by William Russell Birch circa 1800. Library of Congress.

Even within his party, though, Madison faced resistance. John Randolph of Roanoke, an outspoken antiwar Virginia congressman, feared spiraling costs and declared: “Our people will not submit to being taxed.” Randolph was outvoted by the war hawks in Congress (those who supported the war), led by the oratorically powerful Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky, who, late in 1811, sent Madison a bottle of Madeira in celebration of the president’s third annual message to Congress, which addressed the “ominous” indications of belligerency on the part of London. Reacting to a breakdown in negotiations, Madison spoke unabashedly about British intransigence: “With this evidence of hostile inflexibility in trampling on rights which no independent nation can relinquish, Congress will feel the duty of putting the United States into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis, and corresponding with the national spirit and expectations.” Another Kentuckian and a future vice president, Richard Mentor Johnson, termed President Madison’s address a “manly and bold attitude of war.”

Madison has received little notice for his forward posture, as history tends to attribute all war fever to the leaders of the House of Representatives. But the president was by no means positioned in the background. Two decades after his death, his private secretary Edward Coles wrote that Madison may have been less “rampant” than the “noisy politicians” who urged war; but after the fighting commenced, he proved himself “less crouching under difficulties” than most of these verbally energetic men.

Madison was not just a thinker. He was an assertive politician. A little known incident foreshadowed the onset of formal hostilities, with which the president was intimately connected. One John Henry, an Irishman who had lived in the United States before removing to Canada, sold information to the administration that purported to prove that certain prominent New Englanders, who thrived on trade with London, were in cahoots with the British ministry. Desirous of adding Canada to the United States, believing that war with Great Britain would very possibly make this goal attainable, Madison consented to pay Henry the then outrageous sum of $50,000. A threat of disunion—an espionage caper originating in Canada—would be enough to justify a northern invasion. If true, the Henry material, along with British-inspired Indian attacks in America’s northwest, would mean that Canada was no longer a passive country. As US troops pushed north, the border would dissolve. As it turned out, however, John Henry’s papers contained no “smoking gun,” no actual names of Federalist conspirators. The US Treasury was drained of $50,000, which it could ill afford, yet the buildup to war did not abate.

Part of a series of articles titled Madison, Party Politics and the War of 1812 .

Last updated: November 16, 2021