In 1862, a stately brick mansion overlooking the picturesque water gap at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, was converted into "Clayton General Hospital." Long tents were pitched in the yard, and by the third week of July, this former armory paymaster's quarters housed 285 patients.

"I noticed a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc. -- about a load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each covered with its brown woolen blanket" Walt Whitman

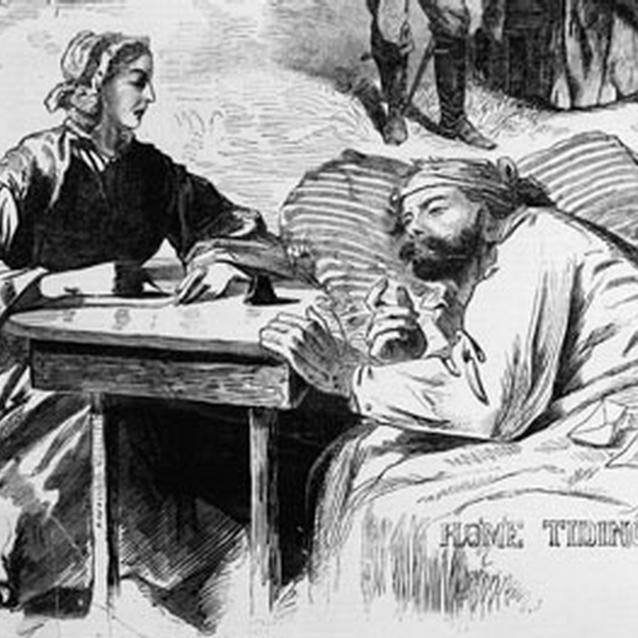

Civilians as Caregivers

Library of Congress

Mrs. Abba A. Goddard traveled over 600 miles from Portland, Maine to care for the soldiers of her hometown's 10th Maine Infantry at Clayton. She was named "Matron of the General Hospital." Despite the limited medical services and comforts provided by the government, Goddard worked to make the hospital as comfortable as possible. Within two weeks of her arrival, she solicited donations from civilians and received seventeen boxes filled with slippers, socks, fans, pin cushions, towels, handkerchiefs and checkerboards.

The future of the soldiers under her care worried the Matron. "When I look at our host of maimed--some without an arm, some without a leg, others minus a foot--and realize their privation is life-long . . . I can hardly restrain my tears."

In early September, the hospital was closed and the patients moved to nearby Frederick, Maryland. "The cause of this sudden removal is a mystery," Goddard reported. "I am informed that some important events are about to transpire." She did not know that approximately 28,000 Confederates were marching on Harpers Ferry and that many more wounded would soon be in need of assistance.

Nearly 10,000 soldiers passed through the Frederick hospitals alone in the aftermath of the Maryland Campaign. Many of the patients who could be safely moved were quickly transferred by railroad to the large hospitals in Baltimore, Washington and Philadelphia. Many others were treated in Frederick until they recovered enough to be transferred, discharged or returned to their units.

The patients were treated by a combination of Army and civilian surgeons, volunteer female nurses, enlisted male nurses, medical cadets, cooks, and laundresses. In addition to the medical staff and employees, many private citizens helped out as they could. Supplemental food, clothing, medical supplies and various personal items were donated to the hospital and the patients by the Frederick Ladies Relief Association and other private groups.

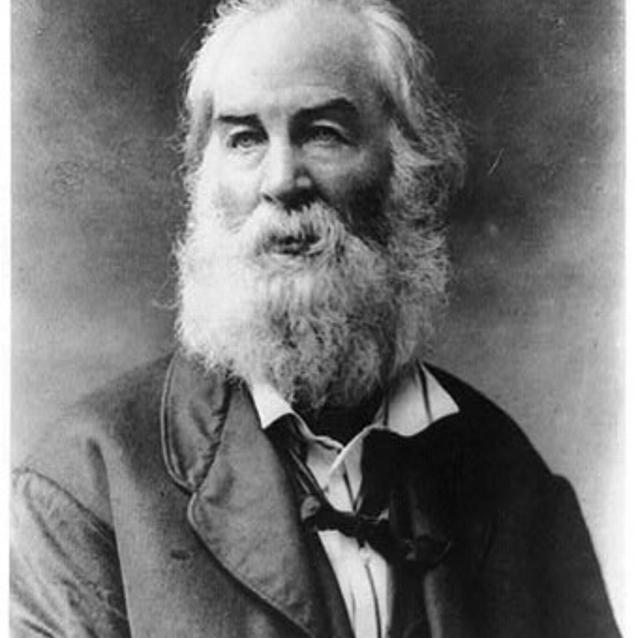

The Poet Who was a Nurse: Walt Whitman

Library of Congress

When the war began, poet Walt Whitman was exempt from service due to age, though two of his younger brothers joined the Union Army. Upon hearing the news of the wounding of his brother, George, in 1862, Whitman left his home in New York to care for him in Virginia. During his mission of mercy, he was overcome with sympathy for all the wounded young men he saw, many of them bound for hospitals in Washington, D.C. After George's recovery, Whitman decided to move to the Capital to care for wounded soldiers. Finding a job as a clerk in an army office, Whitman spent much of his time away from work volunteering in several of the area hospitals. Spending his pay on gifts for soldiers and volunteering his time writing letters for soldiers and changing dressings, Whitman quickly became a beloved and respected figure among the wards. Moved by the suffering of the wounded and stories of the battlefields, he scribbled poetry in his notebook as he moved among the hurt and dying. Many of these poems were included in his 1865 collection, Drum Taps.

"I noticed a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc. -- about a load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each covered with its brown woolen blanket... The house is quite crowded; all the wounds pretty bad, some frightful, the men in their old clothes, unclean and bloody. Some of the men were dying. I had nothing to give at that night, but wrote a few letters to folks home, mothers, etc. Also talked to three or four who seemed most susceptible to it, and needing it." -Walt Whitman

Part of a series of articles titled A Most Horrid Picture.

Previous: From The Front Lines to the Hospital

Next: Organization is Key

Last updated: August 14, 2017