Last updated: December 2, 2021

Article

Studying Arctic Marine Mammals in the Shipping Age

A team of researchers studies how marine mammals, endemic to the Arctic Ocean, will fare as shipping in the region heats up.

Dr. Hauser attributes some of her concerns to an incident from 30 years ago. Although young at the time, she still recalls the sadness, anger and desperation of those around her as news of the Exxon Valdez oil spill hit the streets in her home town of Anchorage. Those impressions, like the oil still pooled beneath the sediment in Prince William Sound, have never dissipated. Now, with her own son about the age she was when the spill occurred, she wonders what environmental impacts will be indelibly etched on his memory.

This study, is, in a sense, an effort to help preempt similar, if not more plodding, incidents from occurring in the Arctic.

We're Looking at a Sea Change

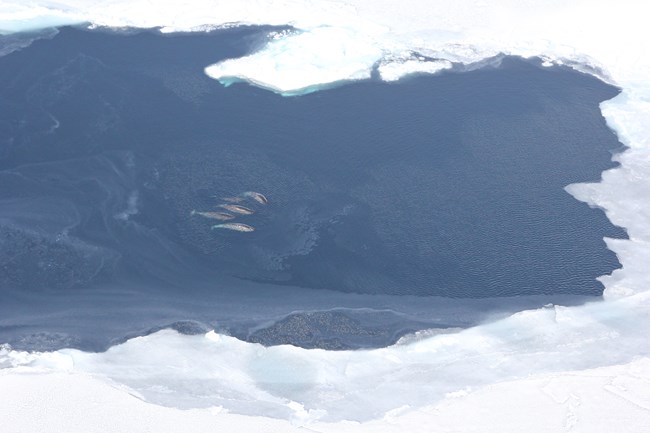

After centuries of ice-bound isolation, two fabled shipping routes, the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route, now sit poised to become major shipping lanes, made passable by a rapidly warming Arctic. Since 1979, September sea ice extent in the Arctic has retreated 14% per decade. Current projections are that by the year 2040, the region will experience summers free of sea ice. (1) In the words of Shiva Polefka, a policy analyst at the Center for American Progress, “Things are changing extraordinarily fast.” (2)While the majority of transits through the Northwest Passage are still made by small, private vessels, that is all but certain to change. On September 16, 2016 the 1000-passenger Crystal Serenity, completed the first full-sized commercial cruise ship transit of the route. (3) It went off without a hitch. By mid-century, such large vessel transits through the passage will, likely, be routine.

The Northern Sea Route, in contrast, already allows the passage of large vessels. However, it too, is becoming increasingly navigable. The year 2018 marked the first time ever a container ship travelled this route. (4)

What those in the shipping industry, and many nations, see as a boon, Hauser sees as an added risk to already stressed Arctic wildlife and coastal communities. According to the study, “the potential impacts … on endemic Arctic marine mammal species are unknown despite their critical social and ecological roles in the ecosystem…” Hauser and co-authors Kristin Laidre and Harry Stern hope that the results of this study will invite a proactive approach for developing marine mammal-safe shipping practices, while Arctic waters are still relatively calm. Hauser also expresses a deep commitment to doing research that matters to coastal peoples, whose lives have been intertwined with these iconic animals for centuries.

The Search for Answers

Vulnerability of Artic Marine Mammals to Vessel Traffic in the Increasingly Ice-free Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route quantifies the effects of shipping on Arctic marine mammals and identifies those most vulnerable. The study, produced by a team of researchers at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks and the University of Washington, and funded by NASA and the Collaborative Alaskan Arctic Studies Program, is the first circumpolar assessment of its kind.The team looked at 80 subpopulations of the seven marine mammals found only in the Arctic: beluga and bowhead whales, narwhals, ringed and bearded seals, walruses and polar bears. Each species studied is a key component of the short Arctic food chain, and serves as a critical cultural and subsistence resource to coastal indigenous communities. They are also all increasingly susceptible to climate change.

To conduct the study, Hauser and her co-authors reviewed hundreds of studies and assigned vulnerability scores to each population based on the combination of sensitivity to vessels and the degree of exposure to sea routes. Sensitivity levels were based on multiple variables, and narrowed into three broad categories: vessel effects (such as disturbance, sensitivity to sound and collisions), frequency of exposure, and ecological factors (such as population abundance and trends). Possible scores ranged from 1-3 for both sensitivity and exposure. These scores were then combined for a maximum potential vulnerability score of nine. The research focused on animal activity during the month of September, when ice is at its lowest levels, and shipping is expected to peak.

The study noted a lack of data on many Arctic marine mammal species and subpopulations, particularly in the Russian portion of the Northern Sea Route and sections of the eastern Canadian Arctic. For example, they found few studies examining vessel effects on ice seals and polar bears. To account for this lack of data, each subpopulation was also assigned an uncertainty score. By identifying knowledge gaps, the authors hope that these uncertainty scores will help direct future monitoring and research.

What Did They Learn?

The study found that 53% of the subpopulations spent time in either the Northwest Passage, the Northern Shipping Route, or both, during September. In general, they found whales to be more vulnerable than seals, due to their high exposure levels. In the Arctic at large, narwhals were deemed most vulnerable to shipping. Their mean score of 5.59 (and as high as 7.5 for one particular subpopulation) is partially attributed to their limited geographic range and heavy presence in the high Arctic in September, in close proximity to shipping routes. Narwhals’ sensitivity to vessel sounds and innately skittish behavior, which causes them to avoid regions where ships are present, also increased their vulnerability rating.

However, scores varied regionally. Bowhead whales, not narwhals, scored highest in the waters off the coast of Alaska. These ratings were based in part on bowheads’ susceptibility to ship strikes due to their size, speed and extended surface time, and the high level of exposure to sea routes by the Alaskan bowhead whale subpopulation. Alaska subpopulations of walruses and beluga whales received high vulnerability scores, as well.

Hauser’s study found polar bears to be the least vulnerable overall, partially because they spend much of their time on land in September, and polar bears are also generally less sensitive to vessels than the other species. Ringed and bearded seals, with generally large, widely distributed populations, were also determined to be less vulnerable. The authors note, however, that the study focused on periods of open water and that the scores may vary depending on the time of year. They cite, for example, the potential for ice-breaking vessels to impact pupping and foraging during colder seasons when seal and polar bear populations use sea ice as a platform.

Finally, the study identified two regions where ship-mammal encounters are particularly likely. The Lancaster Sound in northern Canada and Alaska’s Bering Strait essentially act as geographic bottlenecks, funneling all shipping traffic and marine mammals through narrow passages. Only 53 miles wide in its narrowest point, the Bering Strait provides critical access to Arctic bounty for migrating marine mammals. It is also, however, a key throughway for ships accessing both the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage. Ships and marine mammals passing through these zones were found to be 2-3 times more likely to come into contact than along any other part of either shipping route.

What Can Be Done?

While focusing primarily on assessing marine mammal vulnerability, the study also lists effective conservation-oriented strategies already in place elsewhere. Such practices include avoiding key habitats, adjusting transit timing during migration periods, minimizing sound disturbance, setting speed limits, and developing methods to help ships detect and avoid animals. The study also cites the use of “Dynamic Spatial Management,” which establishes temporary protective zones, or rolling closures, that change in accordance with peak migration activity.Planning for large-scale vessel transit through the Arctic is already well underway. One can almost sense the urgency in Hauser’s voice, when discussing her research. “These are endemic species that have never seen large numbers of big vessels,” she states. “We’re right on the precipice of what could be an emerging risk factor.” She stresses that this is only a first step in addressing issues that are likely to become increasingly important in the Arctic’s rapidly changing ecosystem.

Read the study at: https://www.pnas.org/content/115/29/7617

Tags

- alaska public lands

- bering land bridge national preserve

- cape krusenstern national monument

- gates of the arctic national park & preserve

- arctic

- arctic ocean

- marine mammals

- alaska nature and science

- alaska wildlife

- shipping

- ocean

- ocean alaska

- oaslc

- alaska subsistence

- climate change

- marine animals and birds

- marine ecosystems

- marine traffic

- marine

- arctic science

- ocean alaska science and learning center

- resource brief