The failure of the embargo left the Republicans with two stark alternatives: wage war or submit to British domination on the high seas. The Federalists favored tacit submission as more profitable and less dangerous—given the shrunken and demoralized state of the American military cut to the bone by Jefferson.

The war promised to determine the survival of the American union and republic—and therefore the meaning and success (or failure) of the American Revolution.

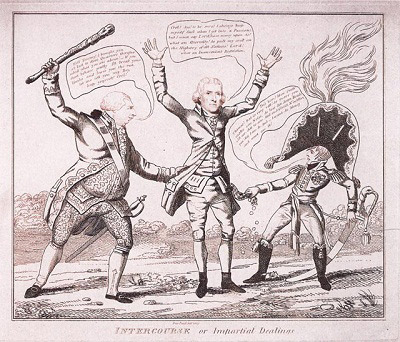

An Argument for War

The Library of Congress

In early 1812, President James Madison and bellicose congressmen, known as war hawks, decided that submitting to British naval domination eroded American sovereignty and imperiled national honor. Averse to the high costs of a bigger navy, the Republicans also hoped to win a war on the cheap by invading and conquering Canada with a new army of volunteers drawn from the state militias.

Conquering Canada also promised to stifle the armed resistance by Indians to westward expansion by American settlers. In the frontier zone south of the Great Lakes, Indians had obtained encouragement and munitions from British traders and officers based in nearby Canada. Republicans insisted that the natives should be their dependents living within a fixed boundary separating British from American sovereignty. But the British treated the Indians as independent peoples dwelling in their own country between the empire and the republic—and thereby free to make their own alliances.

By saving the Indian nations from American destruction, the British hoped to preserve valuable allies for a future, and apparently inevitable, war with the Americans. But that low-level assistance became a self-fulfilling prophecy as the Republicans insisted that the British caused the Indian resistance. In newspapers and Congress, the Republicans blamed the atrocities of frontier war on the British—and vowed to drive them from their bases in Canada.

Despite the nation’s military weakness, most Republicans felt that they had to declare war or lose their credibility. They also desperately hoped that war would galvanize and unify a divided country. Madison later explained that “he knew the unprepared state of the country, but he esteemed it necessary to throw forward the flag of the country, sure that the people would press forward and defend it.” By uniting the country behind a war, and by casting the Federalists as pro-British traitors, the Republicans hoped to ruin their opponents once and for all.

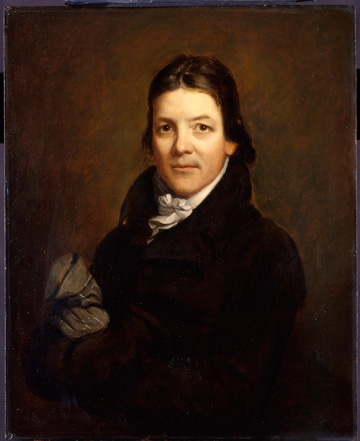

The Cost of Peace

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Mrs. Gerard B. Lambert

The Federalists opposed the war as a military folly in service to a moral travesty, for they favored the British crusade to defeat Napoleon, aptly deemed a bloody dictator who threatened the rest of the world. Launched at the peak of Napoleon’s power, the new American war might help the dictator to defeat the British. In addition, the Federalists dreaded the retaliatory power of the Royal Navy to sweep American ships from the seas and to bombard American seaports.

The Federalists vowed to undermine the war effort, hastening the inevitable American defeats that, they hoped, would discredit the Republicans as inept and corrupt. Disabused of their illusions, the voters would then return the Federalists to power and the nation to peace—so the Federalists dreamed. In the meantime, Federalist merchants meant to profit by smuggling with the British, providing provisions desperately needed by the British garrisons in Canada. In New England, some Federalists even flirted with secession and overtures to the British for a separate peace.

In 1812 Britain’s rulers wanted to avoid a war in America as a dangerous distraction from the pressing struggle against Napoleon. But the British would never relinquish their power to stop and search neutral merchant ships to regulate trade and to seize runaway subjects. And, once forced into a war in North America, the British resolved to teach the Americans a bloody lesson that would undermine their confidence in republican government. The war promised to determine the survival of the American union and republic—and therefore the meaning and success (or failure) of the American Revolution.

Part of a series of articles titled From the American Revolution to the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015