Last updated: September 2, 2025

Article

Species Spotlight - Striped Skunk

What’s black and white and full of stinky stuff? If you said: the newspaper, I’d have to agree. If you said a skunk, however, please allow me to retort. Not only are they avid groomers and maintain a healthy, clean coat, they rarely release their spray. Some people (about 1 in a 1000) can’t even smell skunk odor, and there are those rare souls out there that have even come to appreciate it, maybe a bit like Vogon poetry (IYKYK). Skunks indeed are mostly harmless, and actually have benifical effects for agricultural fields and yards by ridding them of many common insect pests and rodents. Jerry Dragoo, a New Mexico mephitologist (a skunk-specializing biologist), is such a fan and proponent of skunks that he founded the Dragoo Institute for the Betterment of Skunks and Skunk Reputations. A sort of skunk stink tank organization.

Welcome to Skunk Land

There are actually 5 skunk species in North America (12 across North, Central, and South America), but only the striped skunk spans parts of the entire continent. It is also the inspiration behind the love-sick Pepe Lepu cartoon character. When early European colonists first encountered this mostly nocturnal creature here they confused it for a New World version of a polecat - a ferret-like mammal of Europe that also has black-and-white stripes and can also produce a powerful odiferous spray. They eventually began to realize skunks are totally different animals, but the term “polecat” still gets bounced around, especially in the southeastern US. The word “skunk” is an English adaptation of the likely Wabanaki term šeka:kwa, which roughly translates into “peeing bushy-tailed animal”. The great city of Chicago owes it’s name to these mammals as well, as it is the Cree and Ojibwe phrase for “skunk land”. Somehow that is never mentioned in the tourist brochures.

It was only relatively recently that skunks were recognized to be in their own family. Genetic techniques in the 1990’s showed that they were not as closely related to weasels as once thought by the likes of Carl Linnaeus (the godfather of modern taxonomy), and were split in to their own Mephitidae family. The Latin Mephitis means a foul, noxious smell, or a poisonous gas, and is related to the Roman goddess of the same name associated with foul-smelling gases. One can only imagine what her shrine smelled like.

Love Stinks

Striped skunks live in various habitats, but are most comfortable in the transition areas between fields/lawns and forest. They keep a series of burrows (some as long as 20ft), hollow logs, or rock crevices around their territories that they either found, dug, or evicted the previous resident out of - they have been known to steal the burrows of foxes and woodchucks. Skunks move around their territory depending on time of year. For example, the den where they raise their young is seldom the same as the one they spend the winter months in.

On the hibernation spectrum, skunks skew towards the “not true” end because they will become active during certain times of winter. They bulk up in the fall so that they can become mostly dormant, relying on the binge-eating acquired layer of fat to sustain them during the coldest stretches of the season. Skunks will sometimes den communally, using “social thermoregulation” to keep each other warm. They can sleep deeply in a state of torpor for weeks on end, but wake up and even leave their dens on occasion, especially on warm winter days. Another arousal opportunity is the February mating season, where males will wander up to 5 miles to find a receptive mate. On occasion, males will spray each other in mating season tiffs, and females may spray males making unwanted advances.

Female skunks will give birth to on average 4 to 6 kits in late April into May in the northeast, though numbers as high as 10 are not unheard of. The mother raises the young alone for a couple of months in the birthing den until they are ready to accompany her topside on hunting adventures. Once on their own, skunks live relatively short lives with most not lasting more than 2 or 3 years in the wild.

An Odor Most Foul

With the Latin name doubling down on the stinky, it’s clear that a skunk’s most identifying characteristic is its ability to produce and project that pungent, putrid propellant. All carnivores have anal sac glands that they mostly use for territorial scent marking (that of red fox is often confused for skunk spray), but the skunk family have honed it into a powerful personal defense system. Composed of several different compounds of thiols (the same agent that give onions and garlic there powerful potency), the gooey, oily substance has major sticking and stinking power. It’s enough to keep most predators at bay, though Great Horned Owls, with their poor sense of smell and silent attack, are one of the few that are undeterred.

The precision and variety of spray is equally as impressive as its power. Skunks can send a stream of spray targeted to the face of a pursuer or antagonist 10 to 15 feet away. To put that in human context, it’s the equivalent of an average height male accurately aiming a squirt gun into the face of target about 60 feet behind him. They can even customize the type of spray depending on the situation: a stream for a single target of known location, or a spray for multiple targets or an unknown pursuer. Spray mist drifts further than a stream, warding off approachers up to 45 feet away, and is still potent even after drifting for a mile.

Doesn’t Pass the Sniff Test

There are many myths associated with skunks and their spray, including that they spray frequently and often do so out of anger. The truth is that spraying is a last resort and mainly done in self defense. They don’t have many other ways of protecting themselves as they are very near-sighted and their stubby legs don’t make for good climbing or swimming skills. Their very appearance is designed to be a warning to potential predators. The striking black-and-white coloration is a trait called aposematism, and serves as a sort-of flashing danger sign. They also give plenty of warning before spraying, including foot stomping, growling, fluffing up, and spitting. If all that posturing fails, the skunk will bend into a U-shape, take aim, and fire away. A striped skunk stores 2 ounces of spray and can only release it about 3 to 5 times depending on amount per shot. It will need anywhere from 5 to 10 days to fully replenish reserves after being depleted, so it’s important they use it sparingly or otherwise be left without their best defense.

Another persistent myth is that tomato juice is a good remedy to wash skunk spray off pets. While true it can mask it for awhile with it’s own aroma, it does not really get rid of the smell. Because it’s oil-based the spray will need an agent that can break it down. A more effective remedy is to mix 1 qt hydrogen peroxide, 1/4 cup baking soda, and a teaspoon of dish soap. Just be aware that this combination can also lighten hair or fur if not rinsed out completely after a few minutes.

If You See a Skunk - Don’t Raise a Stink About It.

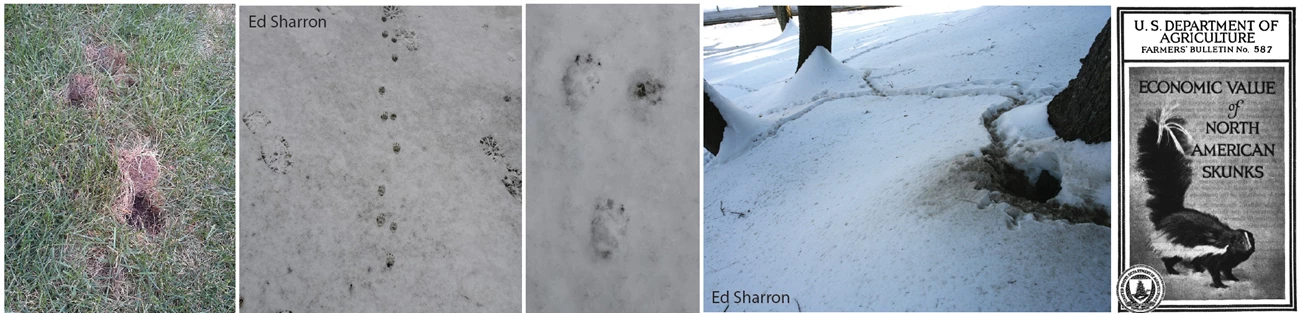

As long as no pets or people end up at the business end of a skunk, they can actually be a valuable occupant of a farm or on your property. These mostly nocturnal, shy, solitary mammals eat a lot things that many consider to be nuisances including insects and mice that they find when traversing their well-trodden mile or so long hunting routes. Skunks are immune or at least highly tolerant to the venom of bees, wasps, and many snake and spider species. They actively dig up yellow-jacket nests or rip open paper wasp hives to eat the protein-packed larvae and pupae or even the adults themselves. Incredibly, skunks can tolerate being stung in the mouth, esophagus, and stomach without any ill effects. They aren’t even rattled by rattlesnakes. Being immune to the venom of several pit viper species including rattlers, cottonmouths, and copperheads, they will fearlessly feed on snakes that most other animals give a wide berth to. The value of skunks was recognized well over a century ago when in 1893 hop growers in NY state appreciated their help in controlling hop-plant borers and lobbied for their protection in some of the country’s earliest mammal conservation legislation. The USDA also helped to educate farmers of a skunk’s benefits to farms in a 1914 Farmer’s Bulletin (see inset).

On the homefront, people will sometimes bemoan the small pockets skunks, as well as raccoons, create in lawns when digging up grubs (essentially beetle larvae). But this can be blaming the symptom, not the root cause of the problem. Skunks are only coming to feast of the grubby goodness often caused by a lawn that is being over watered, getting too much fertilizer, cut too short (leading to shallow roots), and/or not having other plant life in the yard. Grubs arguably do more damage left unchecked creating large patches of dead grass, so skunks are actually doing lawn lovers a solid by reducing their numbers. All too often though, an exterminator is hired to kill the skunk, and then a commercial lawn company is called to spray the lawn with chemicals that kill grubs and pollute the environment.

Tags

- acadia national park

- appalachian national scenic trail

- boston harbor islands national recreation area

- eleanor roosevelt national historic site

- home of franklin d roosevelt national historic site

- marsh - billings - rockefeller national historical park

- minute man national historical park

- morristown national historical park

- saint-gaudens national historical park

- saratoga national historical park

- saugus iron works national historic site

- vanderbilt mansion national historic site

- weir farm national historical park

- species spotlight

- netn

- inventory and monitoring division

- science

- falcons

- striped skunk