Last updated: January 15, 2025

Article

Species Spotlight - Deer Tick

CDC

I know, I know. Ticks? Really? They’re definitely not the most endearing creature to feature, but the more we know about them, the better we can protect ourselves from the ills they spread. An exemplary model to follow is that of the NETN forest health monitoring crew, which through its practices has dramatically reduced the risk of tick bites despite working in some of the most tick-infested of areas in the country. Even though this is one TickTok that will surely never go viral, it may still help you prevent a tick-borne virus or pathogen.

Does a Cold Winter Kill Ticks?

Yes. And no. Well - sometimes. But not really. And even less so than before. To better understand why this is so complicated we need to explore tick biology and behavior, as well as some very recent study findings on disease-carrying ticks.

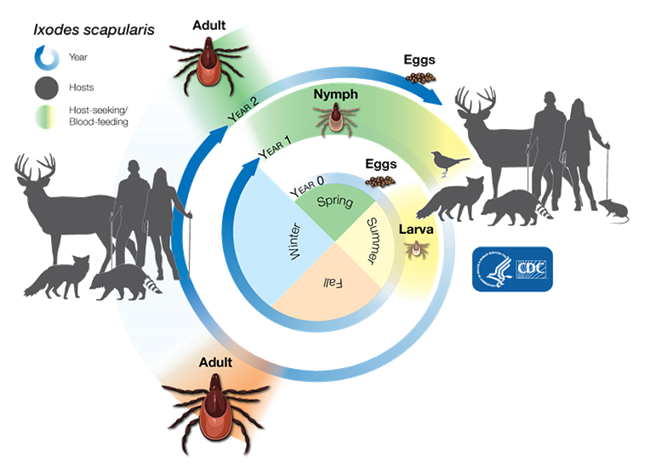

Black-legged ticks (aka deer ticks: the ones that spread Lyme disease among other maladies) live for about 2 to 3 years and mostly in the environment - i.e. not on a host. During their lifetime, they will have up to three blood meals through three life stages: larva, nymph, and adult. Larval ticks that hatched the prior summer but weren’t able to feed on an animal host by the fall seek shelter and become dormant under leaf-litter. Nymphal ticks behave similarly, and are most active in spring and early summer. Adult black-legged ticks, in contrast, reach peak feeding activity in mid-to-late fall which coincides with the time one of their favorite host animals, deer, are actively moving around during their breeding season.

There are actually about 15 species of ticks that call the northeast home. Most of them specialize on a particular host like bats, rabbits, moose, birds, etc. The American dog tick and lone star tick can and do feed on humans, but are mostly inactive in fall and winter. Deer ticks however, only decrease activity when temperatures drop below 35°F, meaning disease transmission risk is still present on warm winter days. It follows that in the northeast the risk of Lyme is lowest from late December to about late March. This is just as much weather-related as it is life cycle-related. The nymphal stage of the tick is most responsible for transmitted cases of Lyme, and by late fall they have molted into adults and spend most of the winter in dormancy. Part of the reason Lyme is on the rise is that as the climate warms, ticks are activating earlier, going into dormancy later, and ‘waking’ during winter more - broadening the risk window.

More Cold (and Hard) Facts.

Bitterly cold winter temperatures alone don’t necessarily mean less deer ticks come spring. For winter to kill them, ticks must remain exposed to very cold temperatures (10°F or less) for several days in a row. This is unusual because of warmer winters and because ticks seldom stay exposed in winter months. Even though they cannot produce their own body heat, these arachnids have other tick-tricks up their sleeves. Most will burrow beneath the leaf-litter as freezing weather arrives. A thick layer of snow acts as an insulating blanket keeping temps hovering right around the freezing point at soil level. Even better, if the tick has attached to a host animal like a deer, the host’s body heat can be plenty to keep it nice and cozy. Equally if not more important than warmth, ticks need moisture to survive. It is the low humidity of winter rather than cold weather that may impact them more. So even if it’s not cold enough to kill them, it could be dry enough to kill them. Here’s hoping for a dry, bitterly cold winter next year. How depressing.

Population is on the Up-tick

As the deer (and perhaps more importantly - mice) population continues to grow and the winter season shrink, it is only providing more opportunities for the deer tick to thrive. But don’t worry, it gets worse. A study published just this year by the Society of Integrative and Comparative Biology found that ticks that carry the Lyme disease microbe do quite well in normal winter conditions when compared to microbe free ticks. That’s right - the diseased ones do the best. During the study more than 600 ticks were put in vials and sampled over three winters with temperatures reaching as low as minus 0.4°F. Amazingly, just under 80% of lyme-infected ticks survived exposure to these very cold temperatures compared to 50% of uninfected ticks.

Ticks carrying the Lyme disease–causing pathogen also were most active during winter warm spells and “woke up” about four days a week (uninfected ticks and ticks kept at stable temperatures woke up just one to two days a week) making tick bites and disease transmission more likely throughout the year. Joy.

It’s Prime-time for Lyme

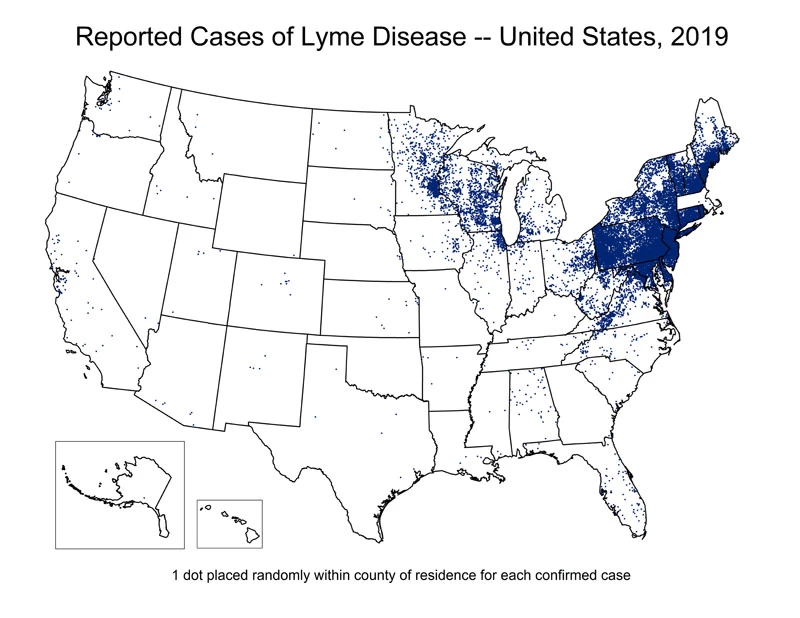

Spring and summer are still the most commonplace time for Lyme in the Northeast, and the North/Northeast are the most common places for Lyme. In the U.S. in 2015, 95% of all confirmed Lyme cases were in the Northeast, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Larval and nymph stage ticks pick up the pathogens that cause Lyme and other diseases from blood meals they take from infected mammals and subsequently transmit those pathogens to whatever they happen to feed on in their next life stage. That could be you, or me, or another animal host that other ticks will feed on (and pick up the pathogen) in the near future. Lyme is not the only risk from a deer tick bite, other microbes that transmit anaplasmosis, babesiosis, powassan and other horrors are also possible, but this article doesn’t include a free dose of Valium, so we’ll leave it there for now. The slightly good news is that if a tick is removed within 24 hours, the likelihood of transmission is very low. Finding a poppy seed-sized nymphal tick however can be difficult, so thorough tick-checking is paramount to prevent illness.

Deer, Mice, ...and Lizards?

While a burgeoning deer population is certainly helping the spread of deer ticks, deer don’t directly have an impact on the spread of Lyme. This is a product of deer robustness to the pathogen and the tick’s life cycle. First, white-tailed deer don’t often get infected, and most ticks found feeding on deer are already adults, meaning this is their last blood meal and they can’t pass on any pathogens to humans. Thusly deer are not good ‘natural reservoirs’ (animals that host pathogens) for Lyme disease. Instead, white-footed mice appear to be a leading, if not the leading, reservoir for Lyme. Other small mammals also play an important role in the spread of Lyme including other mouse species, voles, chipmunks, and shrews. In the western U.S. ticks commonly feed on lizards. The western fence lizard has a blood protein that can kill the bacteria that causes Lyme, and is a major reason why Lyme is so much less prevalent in the West. But what about the southeastern U.S. where Lyme rates are also very low? This even though black-legged ticks, deer and mice are also common there. One animal the southeast has that the northeast doesn’t are five-lined skinks. These smooth-scaled lizards are a preferred host for deer ticks, and are also poor transmitters of Lyme. It is yet unknown if skink blood also has Lyme-bacteria killing proteins, or if something else is at play. Either way it follows that Lyme rates are much lower in the southeast than northeastern U.S. I wonder if we can design little winter jackets for these guys and....nah. Probably a bad idea.

Oak-y Doe-ky.

White-footed mice, deer, and oak trees are part of interlacing web of ecological interdependencies that can actually have an impact on Lyme transmission rates for a particular year. When oaks have a “mast year” and produce copious acorns, mice populations increase. White-tailed deer also heavily feed on acorns. Deer carry adult ticks that drop-off and spend the winter under the leaf-litter of oak forests. Next spring, female ticks lay eggs that hatch into larval ticks that are not yet infected with the bacteria-causing Lyme. They often do become infected when feeding on the mice that have increased because of acorns. Thus the risk of Lyme disease is higher in oak forests two years after a large acorn crop.

It’s The Tick Tack Foe.

It should be abundantly clear by now that our best defense to guard against tick-borne disease, short of surrounding ourselves with lizards, is our own diligence. The I&M forest health monitoring crew can serve as a shining example as to how to behave when exposure to ticks is a risk. Despite spending many hours a day over the course of the summer months in some of the most tick-infested parts of the country, NETN forest crew members have not had a single case of Lyme disease since 2013. They have accomplished this through a strict adherence to their field season tick safety protocol. This includes: treating field gear with Permethrin, wearing long pants with ‘tick gaiters’ going as far as to duct tape their pants to their boots in particularly ticky areas, rolling off with tacky lint rollers after a day in the field (a crew favorite - see quote) before getting into a car, and thorough tick-checks and showers as soon as possible after a field day.

For more information.

- Learn how to safely apply Permethrin to your clothing.

- Find out more about tick-borne disease and tips on finding and preventing ticks in this NPS One Health and Disease article.

Tags

- acadia national park

- appalachian national scenic trail

- boston harbor islands national recreation area

- eleanor roosevelt national historic site

- home of franklin d roosevelt national historic site

- marsh - billings - rockefeller national historical park

- minute man national historical park

- morristown national historical park

- saint-gaudens national historical park

- saratoga national historical park

- saugus iron works national historic site

- vanderbilt mansion national historic site

- weir farm national historical park

- species spotlight

- netn

- inventory and monitoring division

- ticks

- deer tick

- lyme disease