Last updated: January 15, 2025

Article

Species Spotlight - American Oystercatcher

Donald R Miller

It’s a foggy morning in Boston Harbor. On the far flung island of Outer Brewster, a meandering American Oystercatcher has come upon its namesake favorite meal - an oyster: but how to break into the tightly sealed shell that protects the animal’s soft, juicy (and delicious) inner bits? Using a skill that has been honed over thousands of meals, the bird deftly grasps the bivalve in its long orange bill and takes it to a rocky spot high above the surf. Expertly maneuvering the shell, it slams the oyster against the rock right at the point where the adductor muscle is protected inside. After a few blows the shells cracks open and the Oystercatcher quickly severs the muscle with its knife-like bill. The two halves fall apart, acting as sort-of serving trays for the oyster’s soft parts - which are eagerly consumed.

What is it?

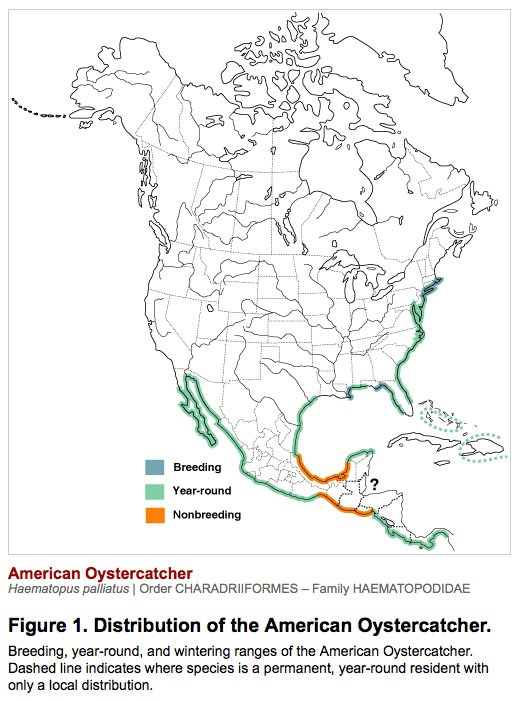

The American Oystercatcher is a large, unmistakable shorebird found along coastal salt marshes and sand beaches. It is one of the few birds that solely specializes on oysters, clams, mussels, and other shellfish living in saltwater. Two races are found in North America: an eastern race along the Atlantic coast from Massachusetts south, and one along the Pacific coast. Historically, the eastern population of birds was abundant until the late 1800’s when they are thought to have been extirpated (made locally extinct) in much of the region as a result of over-zealous market hunting and egg collecting. After the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, their numbers have since steadily increased, but numerous factors including habitat loss from coastal development, human disturbance, and predation have kept their population levels relatively low.

Oystercatchers use their long, knife-like bills to catch shellfish. They either employ the “hammering” technique described above, or jab their bill into the open shell of an unsuspecting mollusk and sever the strong muscle that would otherwise clamp the two halves shut. Sometimes the prey gets the better of the predator, however. If a mussel is firmly attached to a rocky shoreline and it clamps down on the bird’s bill before it can sever the muscle, Oystercatchers may be overtaken by rising tide-waters and drown.

Oystercatchers that breed in the Boston Harbor Islands are migratory. Many of them utilize what’s known as “leapfrog” migration, bypassing other suitable Atlantic coast sites to overwinter on Florida’s Northwest coast. This part of Florida hosts 10% to 15% of the total US population of Oystercatchers during winter, but almost half (~40%) of the Northeast’s breeding population.

Why is it important?

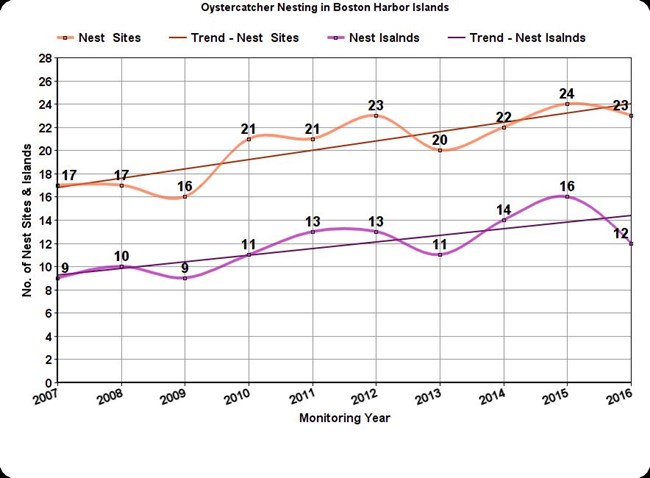

The North American population of Oystercatchers is listed as a high priority shorebird species with high conservation concern in the U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan. They have recently began to recolonize former territory in Massachusetts, going from a handful of pairs in the early 1990’s, to over 20 that breed in the Boston Harbor Islands as of 2016.

Being dependent on marine ecosystems for their entire life cycle, the health of their populations can serve as one measure of over-all ecosystem well-being.

How does NETN monitor it?

Since 2007, volunteers have helped to monitor coastal breeding birds in the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area. Surveys are conducted from mid-May through mid-July of each year. The birds are monitored primarily through boat-based surveys designed to estimate the number of nesting pairs on each island. Oystercatchers tend to nest near shore, are highly visible, and their raucous calls are easily heard. This permits surveyors to slowly circle each island by boat and accurately detect nesting pairs without causing much disturbance to nest sites.

How is it doing?

Over the stretch of its range, Oystercatchers appear to be doing fairly well - even with the disturbances they must tolerate in many of their beach habitats. Although they inhabit coastal areas where human encroachment and habitat loss are threats, large coastal reserves or refuges (most notably in the Mid-Atlantic states) help to protect the bulk of their abundance, especially during the winter months.

In the Northeast, Oystercatchers appear to increasingly be nesting near urban areas, up to 15% according to some findings of NYC Audubon and MA Audubon. Because of this, the American Oystercatcher Conservation Action Plan for the Atlantic Population suggests conservation practices be put in place since these birds face different threats and influences during the breeding season than other segments of the Atlantic population.

The Audubon findings show that the urban estuaries of Boston and New York are providing critical habitat for American Oystercatchers, and their relative abundance has increased compared to non-urban coastal areas. While the overall Massachusetts number of breeding pairs has remained stable for the past decade, relative abundance in urban areas continues to increase. Urban nesting oystercatchers comprised just over 9% of the state population in 2008, but increased significantly to almost 15% by 2015. Equally as impressive, nesting pairs in Boston Harbor have increased more than 40% from 2008 to 2015, even while nesting pairs from non-urban areas have declined by 15% over the same time frame. These numbers are in line with the apparent trend of more pairs establishing territories on more islands in Boston Harbor Islands NRA. Even so, the complete picture of nesting success isn’t totally clear on the islands. NETN’s monitoring program focuses primarily on counting nest sites because it is not possible to monitor nestling fate on a regular basis like it might be on the mainland. Study lead Carol Trocki’s general impression is that nest success in the park “isn’t actually all that great, mainly due to disturbance which increases dramatically over the course of the nesting season” from increased visitation.

Of the 26 islands in Boston Harbor surveyed by NETN in 2015, eight had regular ferry service during the summer season that can bring upwards of 50,000 visitors to each island per year. American Oystercatchers nested on 16 (62%) of the islands surveyed, but only five that had regular ferry service. Oystercatchers are stressed by island landings and other disturbances, leading to greater risks to eggs and hatchlings. Though other factors may have played a role, of the five pairs nesting on islands with high levels of visitation, no chicks were confirmed to have successfully fledged. Only one is known to have fledged the next year.

The long-term success of Oystercatchers in urban estuaries will depend upon respectful coexistence with people near salt marshes and dunes areas, and the availability of high-quality foraging habitat. NETN’s coastal bird monitoring program is an important tool for the park to track and measure their populations amongst its islands, and will help to evaluate the potential effects of climate change, in particular seas-level rise, on these fascinating birds.

For more information

Find NETN’s coastal bird monitoring protocol, reports, resource briefs, and contact information on the Coastal Birds page (http://go.nps.gov/netn/coastalBirds) of our website.