In the sweeping landscapes of the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts, some of the most interesting life around can be found in the dirt right in front of your feet!

But if you stop and look at the ground for a few minutes, you may find a diverse community of tiny organisms, all working together. Biological soil crusts form a living groundcover that is the foundation of desert plant life. They also perform vital ecosystem functions.

Composition and Appearance

Biological soil crusts are made up of cyanobacteria. They sometimes look like areas of "dirty dirt" on the ground. Soil crusts also include lichens, mosses, green algae, microfungi, and bacteria. The visual appearance of soil crusts varies by region. In the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts, BSCs tend to be fl atter and less charismatic than the black, knobby crust more characteristic of the Colorado Plateau. Like many other life forms, desert crusts can often be found growing under a shrub or bush that provides shelter from the sun and wind.

Purpose

Biological soil crusts hold the soil surface together. When wet, cyanobacteria move through the soil and bind rock or soil particles together, forming a web of fibers. Mosses and lichens have small structures that anchor the soil in place. All of these factors help to stabilize the soil, increasing its resistance to wind and water erosion.

Soil crusts don’t even have to be alive to continue their work. Layers of abandoned sheaths, built up over long periods, can still be found clinging to soil particles, providing stability in sandy soils up to 10 cm deep. Other crusts that appear to be dried out seem to come alive when doused with water, like the moss shown at right. Dry and grey when found, a sprinkling of water causes it to become metabolically active again.

Cyanobacteria also convert atmospheric nitrogen to a form plants can use. This is especially important in desert ecosystems, where nitrogen levels are low and often limit plant productivity. Soil crusts also trap and store water, nutrients, and organic matter for use by plants.

Threats

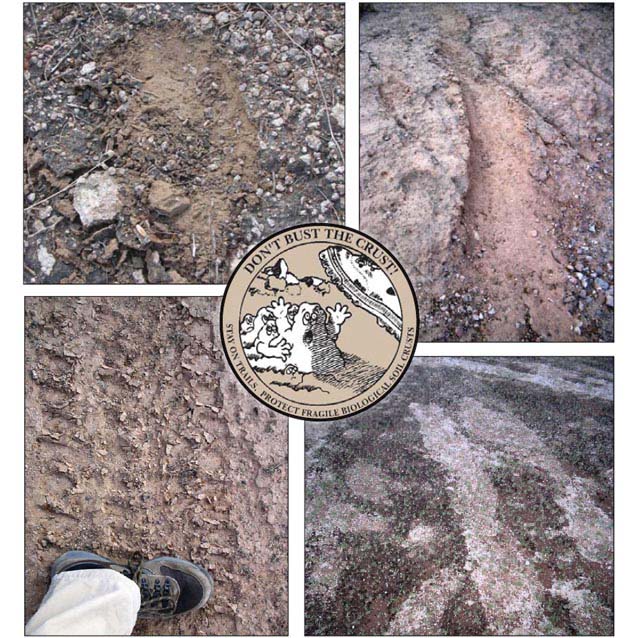

Many human activities can harm soil crusts. Trampling and crushing by footprints or machinery are extremely harmful, especially when the crusts are dry and brittle. Tracks in continuous strips, like those created by vehicles or bicycles, are highly vulnerable to wind and water erosion. Rainfall then carries away loose material, causing channelization. Impacted areas may never fully recover. Although a thin veneer of cyanobacteria may return in a few years, lichens and mosses may take up to 50 years to regrow.

What You Can Do

The best way to avoid damaging soil crusts is simply to stay away from them. Drive and ride on designated roads and trails and steer clear of roadside vegetation. When hiking, always walk on marked trails or other durable surfaces, such as rock or in sandy washes. Keep a watchful eye, and don’t bust the crust!

What We’re Doing

The Sonoran and Chihuahuan Desert networks scientifically monitor the cover and frequency of biological soil crusts at 12 National Park Service units across the Southwest. This gives them an idea of where and how often the crusts occur, and of how much there is. This information will be used to track soil function and improve our understanding of ecosystem health. Monitoring protocols are specifically designed to minimize impact to these fragile communities.

Prepared by the Sonoran Desert Network Network, 2012. For more information, visit www.nps.gov/im/sodn/vegetation-soils.htm or http://soilcrust.org/.

Tags

- big bend national park

- carlsbad caverns national park

- casa grande ruins national monument

- chiricahua national monument

- coronado national memorial

- fort bowie national historic site

- fort davis national historic site

- gila cliff dwellings national monument

- guadalupe mountains national park

- montezuma castle national monument

- organ pipe cactus national monument

- saguaro national park

- tonto national monument

- white sands national park

- swscience

- american southwest

- sonoran desert

- chihuahuan desert

- sodn

- chdn

- soils

- biological soil crust

- desert communities

- cyanobacteria

- moss

- lichens

- deserts

- sonoran desert network

- vegetation and soils

- monitoring

- vegetation

Last updated: November 16, 2018