Last updated: October 24, 2024

Article

Status and Trends of Vegetation and Soils at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, 2008–2016

Every landscape tells a story. In the national parks, ecologists with the Inventory & Monitoring Division return to the same landscapes over time to find out what that story is, and how it is changing.

It’s important to know because vegetation dynamics reflect the health and productivity of ecosystems. Plants either form the basis of—or interact with—all processes in terrestrial ecosystems, so land managers can often manipulate vegetation to achieve management objectives. To do that, they need to know which plants are on the landscape, and whether plant communities are stable or changing.

Background

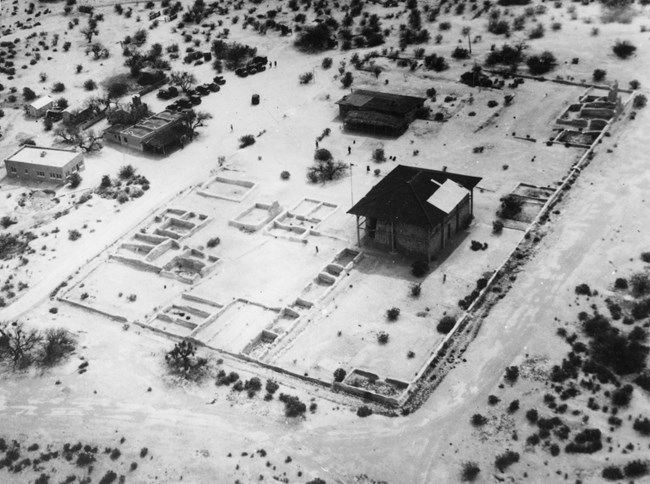

At Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, a 472-acre park in south-central Arizona, much of the landscape looks oddly the same. Created as the nation's first archeological reserve in 1892, the monument preserves an ancient Hohokam Culture farming community and "Great House," a multi-story, earthen-walled structure surrounded by the remains of smaller buildings and a compound wall.

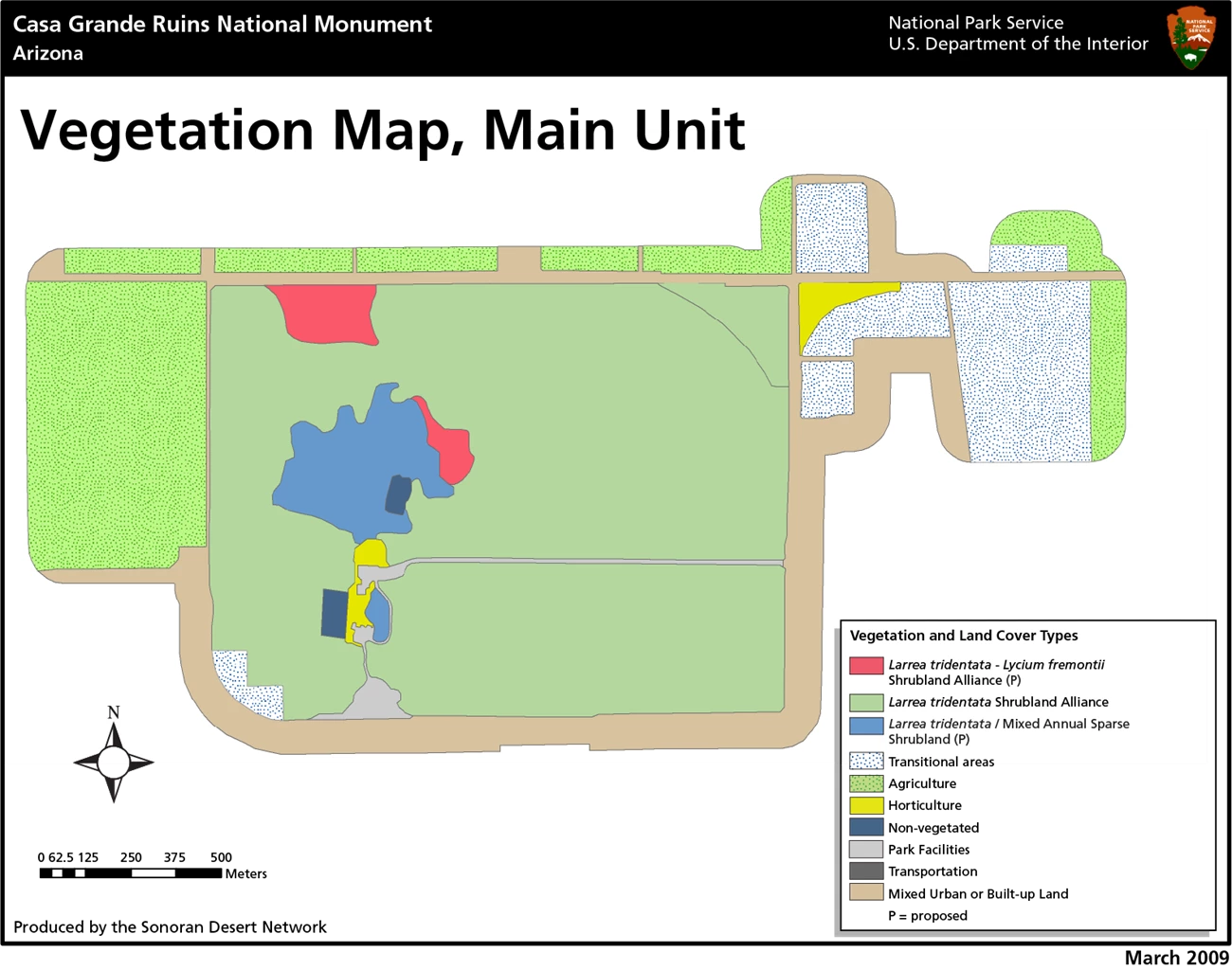

The monument is rich in archeological sites but surprisingly low in plant diversity. To monitor the condition of vegetation and soils, the Sonoran Desert Network establishes permanent, 20 × 50-meter sampling plots. Within those plots, field crew members systematically record the species and height of plants encountered along six transects. (For further details, see the Sonoran Desert Network vegetation and soils monitoring protocol.) They also sample soils for stability and the presence of biological soil crusts.

Monitoring results

Vegetation

From 2008 to 2016, six plots were monitored at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. Three were located near key archeological sites that have recently undergone stabilization efforts. Only one common perennial species was found on all plots: the shrub, creosotebush (Larrea tridentata). Fremont’s desert-thorn (Lycium fremontii) was also found on one plot. No other perennial plant species were detected along transects of any plot during any sampling period. Saguaro cacti (Carnegiea gigantea), an iconic Sonoran Desert plant, was absent from all plots. No invasive exotic species were found, either. The amount of vegetation cover did not change over time for any species.

Soils

What the monument does have in abundance is biological soil crust. The Sonoran Desert Network monitors vegetation and soils together, because the type and condition of soils at a site helps determine what will grow there, and how productive the landscape will be. Biological soil crusts help hold soils in place, preventing erosion. At Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, biological crusts have colonized nearly 60% of the available soil habitat. This is among the highest rates we have observed on Sonoran Desert parks and refuges.

Other soil measures were similarly positive. Overall, the monument has relatively low cover of exposed bare soil (~15%), and soil stability is high. In combination with the nearly flat topography, these results suggest low potential for soil erosion under current conditions. This is good news for management of near-surface archeological sites. However, overall biological soil crust cover was lower on plots that had recently undergone archeological stabilization. On these plots, exposed bare soil comprised approximately half of the soil substrate.

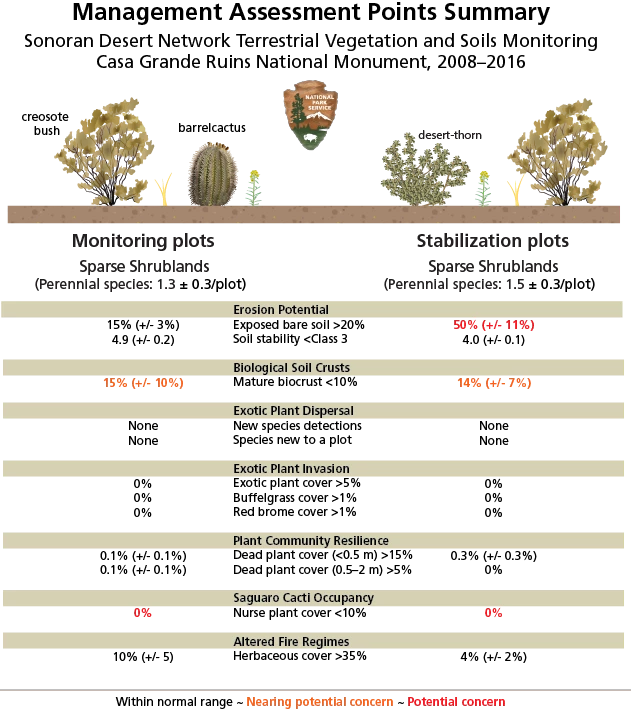

Assessment Points

To link its monitoring with park management, the Sonoran Desert Network uses assessment points as an early warning system for ecological problems. Assessment points give scientists and managers the opportunity to pause, review available information, and consider options. At Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, erosion was identified as a potential issue of concern on the recently stabilized plots. The cover of mature biological soil crusts could not be differentiated from the assessment point on either set of plots. Saguaro cacti recruitment was also of potential concern (see figure).

Linking the Present with the Past

But why is the park landscape a near-monoculture of creosotebush? The answer may lie in the area’s recent—and ancient—history.

In the mid-to-late 1800s, the desert plants at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, particularly the tall mesquite, impressed travelers. One account from 1879 described mesquite hiding the Great House from view until one was nearly upon it. An 1869 survey noted the presence of mesquite, greasewood, and grass. The latter had attracted ranchers to the area by the early 1870s, and cattle ranching prospered for roughly 50 years. In 1902, monument custodian Frank Pinkley reported that cattle had consumed all forage within 100 yards of the Great House. Nevertheless, park records and early visitor accounts describe velvet mesquite woodlands interspersed with native desert shrublands. By the end of the 1930s, though, descriptions of accelerating mesquite mortality on the monument were common. The homogeneity of recent vegetation mapping results and the monitoring described here indicate an apparent endpoint of this directional change: low-diversity desert shrublands.

One likely driver of this change is rapid depletion of local groundwater after the widespread introduction of centrifugal water pumps in the valley during the mid-20th century. The scale of groundwater extraction—effectively, groundwater mining under current climate regimes—is illustrated by soil subsidence (a drop in elevation due to collapsing pore space) of as much as a meter in the area by 1978.

Drawing by NPS/Sarah Studd

Prior to extensive groundwater pumping, established mesquite trees were tapping the relatively shallow groundwater table of the Gila River floodplain. Mesquite is capable of “hydraulic lift,” a process by which a plant’s roots draw water from deep soil layers up to shallow layers. As such, the roots of mesquite trees can enhance soil moisture, while their canopies reduce air and soil temperatures, creating comparatively cool, moist microclimates. These microclimates allow clusters of other plants to grow around the trees.

However, mature mesquite trees are unable to change their root structure quickly enough to keep pace with rapid changes in groundwater depth. Mesquite currently on the monument are scattered and shrubby—likely persisting only on recent precipitation, rather than access to a near-surface water table. With the dramatic decrease in large, mature mesquite trees, the relatively cool, moist microclimates under tree canopies would have rapidly disappeared. The net result has been desertification of the monument’s vegetation since park establishment.

Substantial prehistoric soil disturbance may be another reason for the park’s unusually low plant diversity. The dominant local soil type, Coolidge sandy loam, is well-drained and likely to have been highly impacted by the intensive activities of the Hohokam. Construction of the canal system, irrigated fields, and the large, concentrated clusters of buildings likely entailed enormous excavation, modification, and movement of local soils—much as intensive human development activities do today. Excavation of caliche (a dense carbonate clay layer common in desert soils) for construction of the Great House likely entailed intensive soil disturbance.

These soil disturbances may have influenced infiltration and/or water-holding properties in the rooting zone. Many perennial plants found in other areas with similar climate conditions appear to be unable to survive and reproduce locally under current conditions. Insufficient soil water may be the key.

Recommended Research

Additional research will help us to better understand the monument’s ecology:

- A detailed soil survey would provide key information on erosion potential and other important aspects of natural and cultural resource management.

- A small-scale manipulative experiment could help identify causes of the monument’s paucity of perennial-plant diversity. A germination experiment, using surface soils and biological soil crusts from within the park, could assess germination and recruitment of expected (but absent) native plants under a variety of microclimates that reflect conditions in the monument.

- Compared to conditions in other Sonoran Desert parks, biological soil crusts play an outsized role in nutrient cycling and erosion mitigation at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. A comprehensive, species-level inventory of biological soil crusts would provide an important baseline for these important organisms, and may provide insights into the soil water, fertility, and erosion questions raised in this and other research.

In the meantime, the Sonoran Desert Network will continue to monitor vegetation and soils at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. Future monitoring results will be examined in the context of data already collected to continue to identify trends in vegetation and soil condition at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument and nine other national parks in southern Arizona and New Mexico.

Additional Reading

Information on this page was summarized from: C. L. McIntyre, J. A. Hubbard, and S. E. Studd, 2018. Status and trends of terrestrial vegetation and soils at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, 2008–2016. Natural Resource Report. NPS/SODN/NRR—2018/1800. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado.