Transportation Revolution

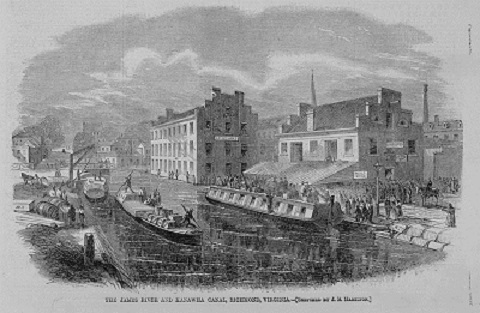

J.R. Hamilton, artist

The Transportation Revolution of the late 1700s and early 1800s fundamentally changed the way people and goods were moved. Canals and railroads helped boost the Virginia population, spread agriculture, and foster manufacturing. They also helped to reinvigorate slavery. Canals, like the James River and Kanawha Canal, were built to help transport shipments between the western counties and the ports near the Chesapeake Bay. By the 1830s and 1840s, railroads were being constructed. This excited people by allowing quick and easy transportation across the state. Market agriculture grew along the James, York, Rappahannock, and Potomac Rivers. Tobacco was in a steady decline and planters needed to find new ways to use their enslaved labor. They wanted to embrace the modernization that the Transportation Revolution brought to society. Enslaved labor had been used for tobacco. How could it be used in manufacturing and mining? How could the planters hold on to their social and ideological values associated with slavery? As they dealt with these questions they adapted to the changing nature of slavery. Some planters moved to other areas of the state, like the Southwest, and spread slave culture. Others experimented with different types of agriculture. Some sold off their slaves to the Deep South to work on cotton plantations. Others decided to hire out their slaves. This changed the way slaves were controlled and managed.

The Confederacy is Born

By the 1850s, Virginia had become a slave society, rather than a society with slaves. Slavery influenced the state's social and political institutions, commerce, and industry. Virginia, like the rest of the nation, was divided on the expansion of slavery in the territories and state's rights. In 1857, the U.S. Supreme court ruled that the federal government had no power to regulate slavery in the territories. The Dred Scott v. Sanford decision also declared that any "negro whose ancestors were imported into the U.S. and sold as slaves had not be an American citizen and therefore had no standing to sue in federal court. The case, which was supposed to solve the slavery question once and for all, ended up creating more tensions between the North and South. Northerns felt the decision was an attack on the ideals and freedoms awarded to them by their states and territories, who opposed slavery. Southerns universally supported the decision, seeing it as the ultimate vindication of their pratice of slavery. A year later, during the campaign for Illinois Senate, Abraham Lincoln, a Northern Republican, declared, "A house divided against itself cannot stand." In 1859, John Brown attempted to start a slave rebellion at Harper's Ferry. Brown was a white abolitionist. He believed that by arming slaves in a rebellion was the only way to overthrow slavery. Brown and several of his men were captured and sentenced to death by hanging. These conflicts over the future of slavery came to a head in the presidential election of 1860. Four candidates vied for the presidency: Abraham Lincoln, Stephen Douglas, John Breckinridge, and John Bell. Lincoln was the Republican party nominee. He believed Congress had no power to establish or legalize slavery in the territories. The Democratic party split into two groups, each with its own ideas about slavery: the Northern and Southern Democrats. Stephen Douglas was a Northern Democrat. Douglas believed that the territories had the right to decide if slavery would exist. John Breckinridge was a Southern Democrat. Breckinridge argued that a citizen had the right to take their property when they moved to a new state. This would include slaves, who were considered property. Bell ran as a candidate for the new Constitutional Union Party (CUP). The CUP was neutral on the slavery issue. It only recognized laws set forth by the Constitution. Lincoln won the election without receiving a single vote from the southern states. He was the first Republican to win the presidency. The announcement signaled the succession of the Southern states.

War hits Virginia

Courtesy of Library of Congress

By the following spring, Virginia and ten other states seceded from the Union. They formed the Confederate States of America and moved the capital from Montgomery, Alabama to Richmond, Virginia. Jefferson Davis was elected its first president. Richmond was a significant industrial center. It gave Confederate forces access to warehouses that served as supply and logistical centers. The James River played an important strategic role in the war. Iron production factories, like the Tredegar Ironworks, produced artillery, ammunition, warship parts, and railroad supplies. The James River and Kanawha Canal moved pig iron and coal from inland to Richmond. Grand homes, such as Violet Bank, Weston, Appomattox, and North Bend, along the James were turned into Confederate and Union lookouts. General J.E.B. Stuart stopped at Edgewood for coffee on his way to Richmond to warn General Lee of the Union Army’s strength. During the Peninsula Campaign, a major Union operation against the Confederate Army, General John Bankhead used Lee Hall as his headquarters between April and May 1862. Other plantation homes, such as Point of Rocks and Burnt Quarter, served as hospitals for the wounded during the war. Two defense lines, Fort Gregg and Fort Whitworth, were maintained on the Mayfield property. General Philip Sheridan occupied Kittiewan as he prepared his army to cross the James River to join the Siege of Petersburg, also known as the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign. The Siege of Petersburg was a series of campaigns fought between June 1864 and March 1865. Led by General Ulysses Grant, Union forces unsuccessfully assaulted Petersburg. Petersburg was crucial to the supply of General Lee’s army and Richmond. Fort Clifton, on the Appomattox River, controlled navigation north of Petersburg. This helped stop Union gunboats from reaching Petersburg. On April 3, 1865, Richmond fell to Union troops. President Lincoln and General Grant met in the library of the Thomas Wallace House to discuss the inevitable end to war and General Lee’s surrender. General Lee and General Grant exchanged several notes and agreed to meet on April 9th at the house of Wilmer McLean. After two and a half hours, General Lee surrendered.

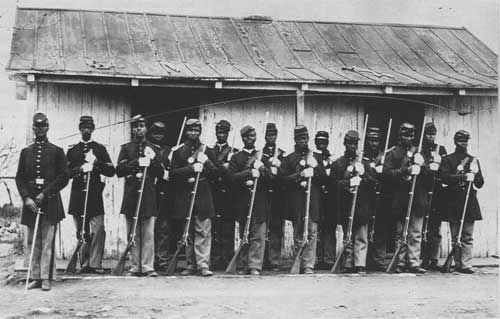

African American Involvement

African Americans were essential in almost every major battle of the war except for Sherman’s invasion of Georgia. When the war started, free African American men rused to volunteer their service to the Union army. Though African Americans had served in both the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, they were barred from enlisting due to a 1792 law. President Lincoln feared that by allowing African Americans to enlist, border states like Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri would secede. However, free African American men were permitted to enlist in 1862, following the passage of the Second Confiscation and Militia act and the Emancipation Proclamation. The Confiscation and Militia act freed slaved who had masters in the Confederate army. By 1863, the Bureau of Colored Troops was established to help mangage the estimated 179,000 African American men in the Union Army. There were an additional 20,000 African American men in the Navy. Fort Pocahontas was built by and manned by the United States Colored Troops. Despite fighting alongside their white counterparts, African Americans soliders did not receive equal pay or treatment. They were paid $10 a month, with $3 deducted for clothing. In comparison, white soldiers recieved $13 a month with no clothing deductions. This continued until June 1864, when Congress granted retroactive equal pay. African American units and soldiers who were captured faced harsher treatment than white prisoners of war. African American men fulfilled other essentail roles during the Civil War, serving as nurses, cooks, and blacksmiths. Though the Confederate army did eventually recruit African Americans later in the war, most African Americans serving in the Confederate army were brought along by their masters to tend to the master's needs. The Union Army also used African Americans as scouts and spies, providing valuable information on Confederate forces, plans, and familar terrain. One of the most famous spies was Harriet Tubman, who also led a raid outside of Beaufort, South Carolina in 1863.

Last updated: September 15, 2016