Last updated: March 1, 2024

Article

Slave Advertisements

![Boston_News-Letter_1704-06-05_[2] (1) Newspaper advertisement for an enslaved man](/articles/images/Boston_News-Letter_1704-06-05_2-1.jpg?maxwidth=650&autorotate=false)

Source: Boston News-Letter, June 5, 1704

In 1704, The Boston News-Letter, published in Boston, Massachusetts, became the first successful newspaper in the American Colonies. Barely a month after the weekly began, an advertisement by local merchant John Colman appeared in the paper on June 5 selling "Two Negro Men" along with a "Negro Woman and Child." This marked the beginning of a 77-year period in which local merchants placed advertisements for enslaved persons in local Boston newspaper.[1]

The Boston News-Letter soon became overtaken by The Boston Gazette, which began publication in 1719. From 1719 to 1781 the paper printed 1,103 different "slaves for sale" ads. These ads led to the selling of over 2,500 individuals.[2] They also provide insight into the slave trade in Boston, such as information on the location of the sale of enslaved persons in the town. Boston did not have a single slave marketplace; rather, the sale of enslaved persons occurred on ships or at various places of business near Long Wharf. The September 30, 1728 Gazette gives an example of a location for the sale of enslaved persons. This ad stated "To be sold at No.24. on the Long-Wharf, Good Barbados Sugar: also two likely Negro’s Male and Female, by Jonathan Sewall…"[3]

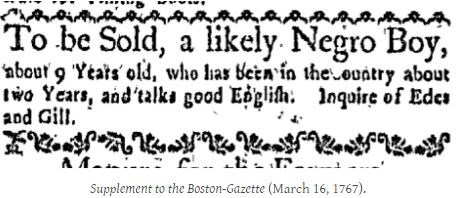

Supplement to the Boston-Gazette, March 16, 1767

Slavery in Massachusetts existed on a much smaller scale than the Southern colonies. Still, the enslaved population rose drastically in Boston in the 1700s. According to historian Jared Hardesty, "in 1704 there were 400 slaves living in Boston, while in 1752, there were 1,541 slaves, an increase of over 350 percent."[4] Newspaper advertisements for enslaved persons during this period highlight the growth in the trade and illustrate the use of enslaved labor in the town.

For Boston's elite, owning an enslaved person demonstrated their wealth. Rich merchants, such as Peter Faneuil and John Hancock, enslaved multiple people on their estates. As one advertisement from The Boston News-Letter stated,

Several likely young Negros of both Sexes, lately imported from the West Indies, fit for either Town or Country Service, among whom is a choice Negro Man, suitable for a Gentleman's Family: To be Sold..[5]

Below the elite of Boston, artisans and others from the laboring class also enslaved people, but for different tasks. The artisans and laborers often enslaved one or two individuals to work in shops, households, or on farms.

Different from the large-scale chattel slavery in the South, enslaved individuals in Boston had a varying skillset that is reflected in newspaper advertisements. In his analysis of "slave for sale" ads in Boston, historian Robert Desrochers Jr. found references to skills such as cooking, gardening, caulking, barrel making, tailoring and blacksmithing.[6] Often times, advertisements, such as the 1732 Boston News-Letter advertisement mentioned above, highlighted the enslaved persons slaves' ability to perform a wide range of indoor and outdoor tasks remained by far the trait Massachusetts masters desired most.[7]

In addition to a diverse skillset, many sellers of enslaved persons wished to remain anonymous. According to Desrochers, in the 1720s 70% of ads included the names of the sellers. By the 1740s, advertisements that included names fell to 20%. As popular opinion began to turn against the slave trade, sellers preferred to keep their names out of print.

![Boston_Gazette_1781-12-10_[4] Newspaper ad for enslaved women](/articles/images/Boston_Gazette_1781-12-10_4.jpg?maxwidth=650&autorotate=false)

Boston Gazette, December 10, 1781

Footnotes

[1] Robert E. Desrochers Jr, "Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781," The William and Mary Quarterly 55, no. 3 (2002), 623.

[2] Ibid. 623.

[3] Boston Gazette. Boston, MA. September, 30, 1728. p.2.

[4] Hardesty, Jared. Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in 18th Century Boston (New York: New York University Press, 2016), p. 22.

[5] Boston News-Letter. (Boston, MA), December, 28, 1732.

[6] For a complete list of professions see Robert E. Desrochers Jr, "Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781," The William and Mary Quarterly 55, no. 3 (2002), 631.

[7] Ibid. P. 630.