Last updated: September 20, 2023

Article

Skagway: Gateway to the Klondike (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Majestic mountains rise abruptly on either side of Skagway, a town situated in a narrow glaciated valley at the head of the Taiya Inlet in Alaska. Positioned along one of the main transportation corridors leading to Canada's interior, Skagway was established as a result of a gold strike in the Klondike region of Canada's Yukon Territory. Beginning in the summer of 1897, thousands of hopeful stampeders poured in to the new town and prepared for the arduous 500-mile journey to the gold fields. Realizing the grueling challenges that lay ahead on the route and the economic potential of supplying goods and services to other stampeders, some chose to remain in Skagway and establish a permanent community. Although it lasted but a brief period, and few obtained the wealth they dreamed of, the Klondike Gold Rush left a lasting mark on the Alaskan and Canadian landscapes. Today, Skagway's "boomtown" era remains alive in the many turn-of-the-century buildings that survive. The city now hosts half a million tourists annually and has a year-round population of approximately 800.

About This Lesson

The lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Skagway and White Pass District" (with photographs), and other materials about the town and the Klondike Gold Rush. It was written by Ardyce Czuchna-Curl, a former park ranger at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson will help students understand the impact of the Klondike Gold Rush on the development of Skagway, Alaska. It can be used in units on western expansion, late 19th and early 20th-century commerce, and urban history.

Time period: Late 19th to early 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Skagway: Gateway to the Klondike relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

-

Standard 1B- The student understands the rapid growth of cities and how urban life changed.

-

Standard 1C- The student understands how agriculture, mining, and ranching were transformed.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Skagway: Gateway to the Klondike relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard B - The student describes the role that supply and demand, price incentives, and profits play in determining what is produced and distributed in a competitive market system.

Objectives for students

1) To explain the impact of the Klondike Gold Rush on Skagway, Alaska.

2) To trace the development of Skagway from a homestead, to a gold rush boomtown, to a permanent city.

3) To describe some of the buildings in Skagway and explain what they can tell us about the people and the city.

4) To examine local buildings that help tell the story of their community's development.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

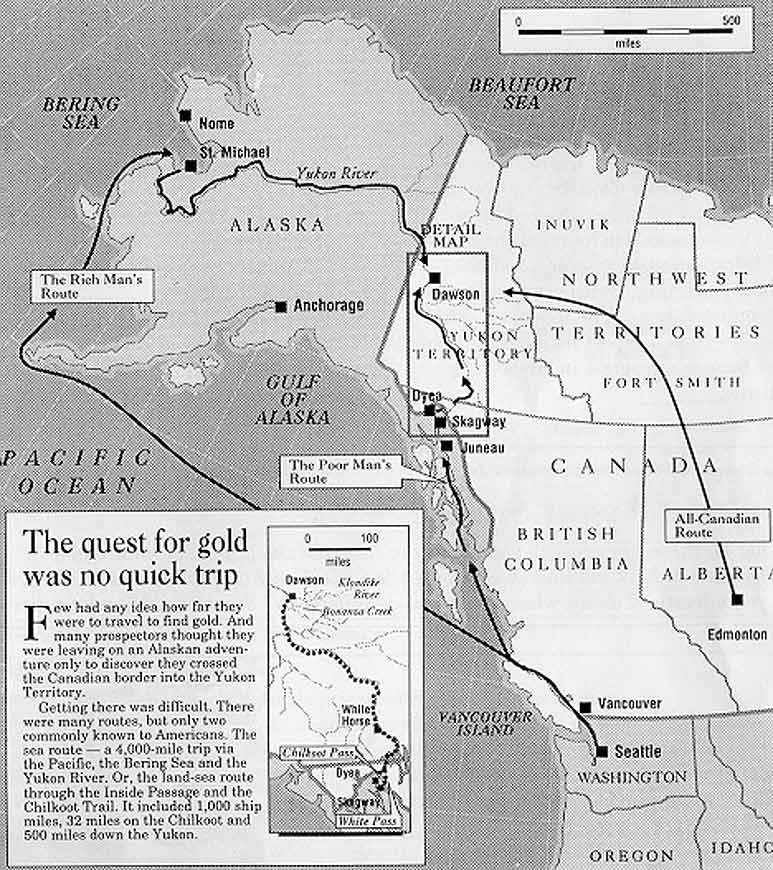

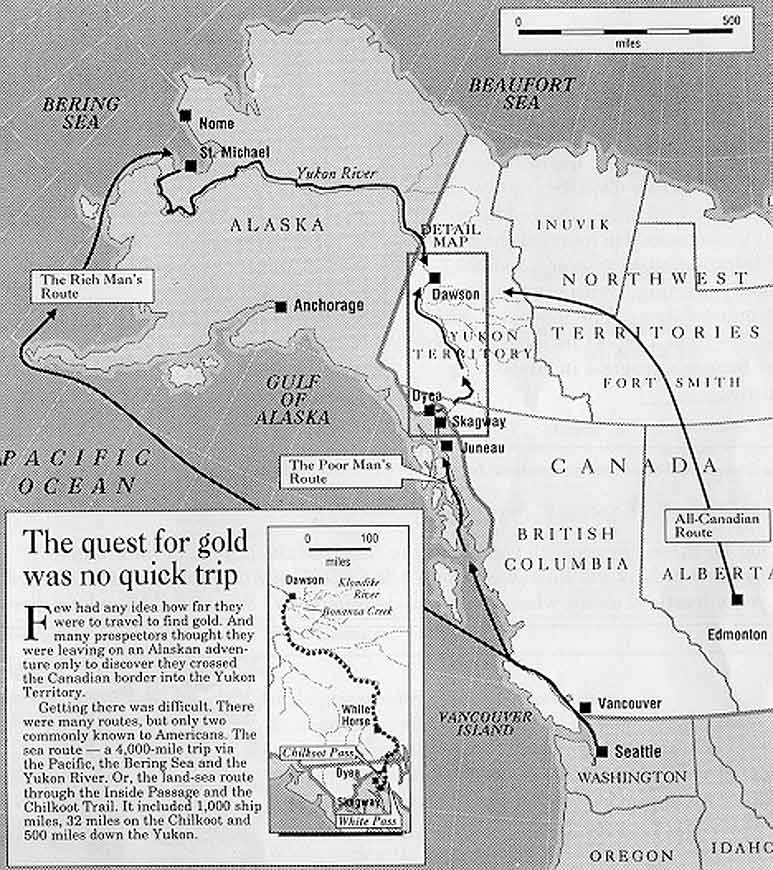

1) two maps of the routes to the Klondike gold fields, and Chilkoot and White Pass Trails;

2) three readinsg to understand the impact of the Klondike Gold Rush on Skagway, Alaska and how buildings can help reveal the stories of a community's past;

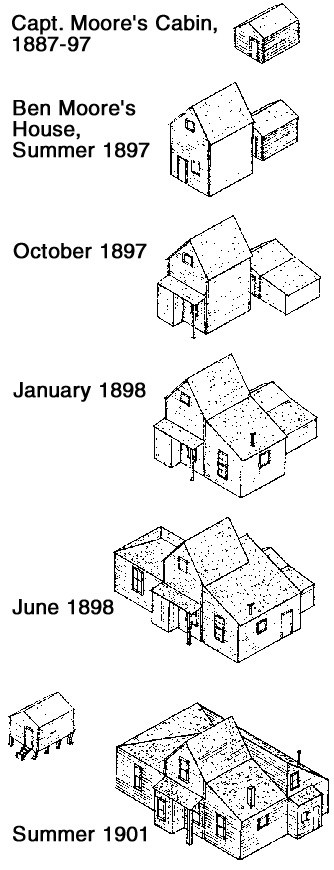

3) a drawing of the historic development of William Moore Cabin and Ben Moore House;

4) six photos of Skagway, Alaska and its historic buildings.

Visiting the site

Skagway is located approximately 100 miles north of Juneau, Alaska, at the northern tip of the Inside Passage in Southeastern Alaska. The Skagway Historic District, Dyea and Chilkoot Trail, White Pass Trail, and the Pioneer Square Historic District in downtown Seattle, Washington, make up Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. The Skagway unit Visitor Center is open - June, July, August: 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. daily , May - September: 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. daily. Winter: variable open hours. The administration building is open Monday through Friday throughout the year. The Trail Center is open 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. daily, mid-May to September. For more information write to the Superintendent, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, P.O. Box 517, Skagway, Alaska, 99840 or visit the park's Web pages.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What purpose might this area have served?

When might it have been constructed?

Setting the Stage

In August 1896, prospectors George Washington Carmack, Skookum Jim, and Dawson Charley discovered gold on Rabbit Creek (renamed Bonanza Creek) in the remote Klondike region of Canada's Yukon Territory. News of the Klondike discovery spread slowly over the next year until miners began to return with their fortunes. In July 1897, the S.S. Portland arrived in Seattle, Washington, with more than a ton of Klondike gold on board. This event touched off the great Klondike Gold Rush as thousands of people who dreamed of becoming wealthy began booking passage on steamers heading north from Seattle and other West Coast ports. Upon arriving at the northern end of the Inside Passage, however, these adventure-bound stampeders found no easy route leading to the still distant Klondike region. The most direct route involved climbing over either the White Pass Trail from Skagway, Alaska, or the Chilkoot Pass Trail from Dyea (pronounced Die-ee) to Bennett Lake, the headwaters of the Yukon River. Stampeders then had to build a boat to navigate 500 miles down the Yukon River. Their final destination was Dawson City, a town that developed near the gold fields. Between 1897 and 1900 more than 100,000 people, from many nations and from all walks of life, set out on the arduous journey to the Klondike. No more than 40,000 actually reached Dawson City, however, and only a few obtained the wealth that they dreamed of along the route.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Routes from Seattle to the Klondike gold fields.

Questions for Map 1

1. Identify the boundaries of the United States and Canada.

2. Locate Seattle, Skagway, Dyea, and Dawson City. What role did each city play in the Klondike Gold Rush?

3. Trace the "poor man's route" and the "rich man's route" to the gold fields near Dawson City. How long was each route? Why do you think the "poor man's route" was the most used? What might have been the advantage of taking the more expensive and longer "rich man's route?"

Locating the Site

Map 2: Chilkoot and White Pass Trails.

The Chilkoot Trail, stretching from Dyea to Bennett Lake, had been used by the Tlingit Indians as a trade route for hundreds of years before the Klondike Gold Rush. The White Pass Trail was a newer route that stretched from Skagway to Bennett Lake. Once stampeders arrived at Bennett Lake they had to buy or build a boat to navigate down the Yukon River. When the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad was completed in 1900, it was no longer necessary to use these treacherous trails. (The railroad route shown on the map generally follows the White Pass Trail.) Travel through the region by car became possible in 1978 with the completion of the Klondike Highway.

Questions for Map 2

1. Find the approximate locations of the two trails on Map 1.

2. Trace the routes of the Chilkoot Trail and White Pass Trail and use the scale to determine the approximate length of each.

3. According to the map, what natural features did stampeders encounter on each route?

4. Trace the railroad route from Skagway to Bennett Lake. Why would it have been difficult to build this railroad line?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Gold is Discovered in the Klondike

William Moore, a former steamboat captain who lived more than 500 miles from the site of the gold strike in Canada's Yukon Territory, had long believed that gold lay in the Klondike because it had been found in similar mountain ranges in South America, Mexico, California, and British Columbia. He was so certain, in fact, that in 1887, he and his adult son Ben claimed a 160-acre homestead at the mouth of the Skagway River in Alaska. Moore settled in this area because he believed it provided the most direct route to the Yukon Territory and, therefore, to potential gold fields. He and his son built a log cabin, a sawmill, and a wharf in anticipation of future gold prospectors passing through on their way to the Klondike. Although he was not interested in mining himself, Moore hoped to profit from the business gold prospectors or "stampeders" would bring as they passed through his property.

Moore was well acquainted with the north country. As a member of an 1887 boundary survey expedition he had made the first recorded investigation of a pass over the Coast Mountains which later became known as White Pass. White Pass appeared to be a possible route for a wagon road across the mountains and into the interior of northern Canada. Although the nearby Chilkoot Pass had been an established trade route used by the Tlingit Indians for hundreds of years, the terrain was too steep for a wagon road. The 2,900-foot White Pass summit was several hundred feet lower than that of Chilkoot Pass. By the time gold was discovered in the Klondike in 1896, Moore had applied to the United States and British Columbia governments for permits to build a wagon road over the White Pass summit. He envisioned a town developing in the valley and expected to earn money selling lumber and charging fees to use his wharf and wagon road.

The trickle of miners who had previously used the White Pass and Chilkoot Pass Trails became a torrent when news of the Klondike discovery reached areas outside of Alaska and northern Canada in July 1897. Stampeders had to pass through the Moores' property to reach the White Pass Trail. To get to the Chilkoot Trail they had to pass through the new town of Dyea (pronounced Die-ee), located a few miles west. The first swarm of stampeders who chose to attempt the White Pass Trail arrived at the Moores' homestead in late July and early August 1897. Here they hastily set up tents and prepared for the next leg of their long journey. Frustrated by reported conditions on the poorly marked and narrow White Pass Trail, some stampeders decided to remain in the Skagway River valley. The Moores had no choice but to let them plat a town site over their homestead. Ignoring the Moores' claim to the property, self-appointed town government officials forced the family onto a five-acre tract and established the town of Skagway. The stampeders who continued to pour into the newly-created Alaskan tent city of Skagway found the conditions primitive. Tents lined the muddy streets, while horse manure and sewage filled the alleys. Lack of government protection led to widespread crime.

By September 1897 conditions on the treacherous White Pass Trail had deteriorated to such a degree that it was virtually impassable. Of the estimated 5,000 stampeders who started over this trail in 1897, only about 10 percent made it through successfully.¹ One gold rush participant claimed that "men are quitting the struggle every day and as we go along we see strong men coming back with tears running down their cheeks, completely broken down, and the stream of humanity passes on, paying no heed to their sufferings."² On the trail stampeders faced disease, malnutrition, and death due to murder, suicide, avalanches, and hypothermia. To make matters worse, the trail had become littered with the corpses of several thousand horses that had broken their legs or strained themselves hauling the stampeders' supplies through knee-deep rocks and mud. The trail soon earned the grim title "Dead Horse Trail." During this period most stampeders used the steeper but shorter Chilkoot Pass Trail from Dyea. Conditions along the White Pass Trail did not improve until the ground froze in late fall.

During the first year of the Klondike Gold Rush stampeders spent an average of three months transporting their supplies or "outfits" up the trails and over the passes to Bennett Lake. Both the White Pass and Chilkoot Pass Trails were less than 40 miles long, but stampeders could only haul a portion of their tremendously heavy supplies at one time. They covered hundreds of miles as they moved some supplies a short distance and then retraced their steps for the next load. Those that made it to Bennett Lake at the headwaters of the Yukon River still had to travel more than 500 miles by boat to reach Dawson City. The length of the journey to the gold fields and the desolate conditions along the way led the Canadian North-West Mounted Police to issue an order in February 1898 requiring stampeders to have a year's supply of food and equipment in order to enter Canada. They enforced this order at border crossings.

Between 1897 and 1900 more than 100,000 people set out for the Klondike. However, no more than 40,000 actually reached Dawson City. Realizing the time, money, energy, and endurance necessary just to get to the gold fields, many stampeders gave up their quest for gold. Some did not continue because they heard that most of the claims already had been staked. Some stampeders learned of an avalanche that occurred on April 3, 1898, on the Chilkoot Trail, killing approximately 70 individuals. Others heard tales of fellow stampeders who lost everything in the rapids of the Yukon River. Still others did not have sufficient supplies or money to continue the arduous journey.

Although most stampeders eventually returned to their homes, some decided to settle in the booming town of Skagway and earn a living providing goods and services to those who continued on to the Klondike. Certain of these men and women opened businesses with money they had planned to spend on their supplies. Some worked for merchants or packed goods over the trail for miners. Many of these entrepreneurs probably made a better life for themselves in Skagway than those who struggled on to the gold fields, where few found gold, and many lost everything. Regardless of their situation, however, these men and women participated in an adventure to remember for the rest of their lives.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why did William Moore claim a homestead in Alaska? How did he and his son prepare for a gold strike?

2. How was the town of Skagway established? Describe the initial conditions in the town.

3. What hardships did stampeders face on their way to the gold fields?

4. Why did some people choose not to continue to the gold fields? What did they do instead? What might you have done in a similar situation?

Reading 1 was adapted from Catherine H. Blee, Paul C. Cloyd, and Robert L.S. Spude, "Historic Structures Report for Ten Buildings," U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984; and Robert L.S. Spude, "Skagway, District of Alaska 1884-1912: Building the Gateway to the Klondike," Report prepared as a cooperative effort of the Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and National Park Service Alaska Regional Office, U.S. Department of the Interior, September 1983.

¹Robert C. Kirk, Twelve Months in Klondike (London: Wm. Heineman, 1899) 38-9.

²San Francisco Chronicle, August 31, 1897.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Settlement and Commerce: Buildings Tell a Story of Growth

Within a short time, Skagway progressed from a homestead, to a hastily-constructed boomtown, and finally to a permanent city. William Moore's log cabin, which he built in 1887, was the first permanent structure in the Skagway River valley. By the time the stampeders arrived in the summer of 1897, Ben Moore (1865-1919) had built a 16-foot by 14-foot, story-and-a-half wood frame house next to the original cabin to accommodate his growing family. The tent city created by stampeders began disappearing by the fall of 1897 as settlers replaced tents with buildings. Structures ranging from simple wood frame shacks to large false-fronted buildings soon covered the town site. Stores, saloons, and offices lined the muddy streets. By March 1898, residents boasted that Skagway was the "Metropolis of Alaska" and the most prosperous town on the North Pacific Coast. A population estimate reported 8,000 residents during the spring of 1898 with approximately 1,000 stampeders passing through town each week. By June 1898, with a population estimated at between 8,800 and 10,000, Skagway was the largest city in Alaska.

Skagway's settlers were anxious to set up stores to sell supplies and services to their neighbors and stampeders. The Goldberg Cigar Store was typical of the earliest businesses that merchants quickly established in the new town. Annie Leonard, the first woman to stake lots in Skagway, constructed a 12-foot by 30-foot building of recycled mismatched lumber and packing crates. D. Goldberg probably arrived in Skagway during the fall of 1897 and either leased or purchased the building from Leonard. His cigar store prospered during the height of the Klondike Gold Rush. An advertisement in the Skagway News, September 16, 1898, lists his stock of goods: "Everything Fresh. Fruits, Confectionery, Cigars, Tobacco, Nuts, Cakes, Candies, and Dried Fruits."

Many of Skagway's small businesses doubled as homes for the owner and his family. Richard C. (Dixie) Anzer's description of his father's shoe shop provides information on one such arrangement:

A big black wooden replica of a man's shoe with the word "maker" painted on it, the typical symbol of a cobbler...was attached to the building. It was about fifteen feet wide with a fairly large window in front and about thirty feet deep.... My father pushed aside a gray blanket which served as a partition and we entered the rear of the shop, which comprised the sleeping quarters and kitchenette. There was a double bunk and father said the upper deck was for me. "Just unpack what you need, he suggested, and hang it on those nails." A large tin basin with a pitcher filled with water stood on a table and the inevitable chamber [pot] underneath. Behind another blanket partition were cooking utensils, a small stove, a table and two chairs.¹

As entrepreneurs prospered they hired builders to construct more permanent buildings. Herman Kirmse was one early successful entrepreneur in Skagway. In 1897 Kirmse opened a jewelry and watch repair shop in a tent he shared with a cobbler. Within a few months he opened Pioneer Jewelry Store on Sixth Avenue. In 1903, well after the gold rush had ended, Kirmse purchased a two-story wooden frame store on 5th and Broadway. In 1906 he expanded into the adjacent structure and remodeled it with large display windows. Native carvers created jewelry and curios for the shop. Still standing today, the building exhibits features typical of the era such as a false front, decorative brackets, and metal roof.

Skagway's permanent residents began establishing a community within a few months of the town's founding. Church groups organized and held services, elementary schools opened, and the first issue of the Skagway News appeared. Townspeople contributed money and labor to build a community hall, which several denominations shared with Skagway's first school. An Episcopalian and a Methodist missionary arrived in March 1898. In 1900 Skagway had five churches: Baptist, Catholic, Episcopal, Methodist-Episcopal, and Presbyterian. In 1899, when the Methodist Episcopal Church determined that the community needed a school of higher education to serve the nearly 400 children who soon would finish elementary school, members built McCabe College. Classes taught at the new school, according to an article in the Daily Alaskan, December 24, 1899, included arithmetic, orthography, penmanship, algebra, geometry, rhetoric, chemistry, geography, U.S. History, Latin, German, French, English, English grammar, and physiology.

The White Pass and Yukon Route company began laying railroad tracks along Broadway in Skagway in May 1898. The railroad depot was constructed between September and December 1898. Railroad employees hastily assembled the two-story wall sections on the ground and then raised them into place. Part of the building's original interior walls were made of rough boards torn from packing crates. Newspaper and sawdust served as insulation. By 1900 railroad officials wanted to send a message of stability to the public. To do so, they hired a Seattle architect to design an elegant general office building next to the depot.

Not surprisingly, Skagway's most prosperous or "boomtown" era ended when the tremendous rush of stampeders passing through the town slowed down in late 1898. At the turn of the century, Skagway's permanent population was little more than 3,000.² It had dropped to below 900 by 1910. Despite the end of the gold rush and a dramatic decrease in population, Skagway continued to survive. Between 1900 and 1920 Skagway's population consisted mostly of railroad employees, merchants, and some miners. The railroad helped promote tourism and by the 1920s the Dead Horse Trail and other sites associated with the gold rush had become some of Alaska's best known tourist attractions.³

Today about 100 buildings from the 1898-1910 era remain. Fifteen have been restored by the National Park Service as part of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. Together, these buildings remind us of the entrepreneurial spirit that led people to settle in this Alaskan town.

Questions for Reading 2

1. What evidence in the reading indicates that Skagway was becoming a permanent community as opposed to simply a supply station for people on their way to the Klondike gold fields?

2. What do the businesses and institutions tell you about the occupations and daily lives of Skagway's residents?

3. Why did Skagway's population drastically decline by 1910? What happened to the town after that?

Reading 2 was adapted from Richard C. Anzer, Klondike Gold Rush as Recalled by a Participant (New York: Pageant Press, 1959); Catherine H. Blee, Robert L.S. Spude, and Paul C. Cloyd, "Historic Structures Report for Ten Buildings," U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984; Alison K. Hoagland, Buildings of Alaska (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); J. Bernard Moore, Skagway in Days Primeval (Skagway: Lynn Canal Publishing, 1997); and Robert L. S. Spude, "Skagway, District of Alaska 1884-1912: Building the Gateway to the Klondike," Report prepared as a cooperative effort of the Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and the National Park Service Alaska Regional Office, U.S. Department of the Interior, September 1983.

¹Catherine H. Blee, Paul C. Cloyd, and Robert L.S. Spude, "Historic Structures Report for Ten Buildings," U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984, p. 149.

²Robert L.S. Spude, "Skagway, District of Alaska 1884-1912: Building the Gateway to the Klondike," Report prepared as a cooperative effort of the Cooperative Park Studies Unit, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and the National Park Service Alaska Regional Office, United States Department of the Interior, September 1983, pp. 11, 27, 46.

³Frank Norris, Gawking at the Midnight Sun: The Tourist in Early Alaska, Alaska Historical Commission Studies in History No. 170 (Anchorage, 1985), pp. 124-29.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Transportation: The Key to Skagway's Survival

Although Skagway is located more than 500 miles from the gold fields in the Klondike, the town benefitted from the discovery because of its location along a transportation route to Canada's interior. The Klondike Gold Rush established Skagway, but its ice-free, deep water port and the completion of a railroad to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, in 1900 kept the town alive.

William Moore's investigation of White Pass and his knowledge of past gold strikes led him to stake a homestead in Alaska's Skagway River valley. His dream to profit from the stampeders' use of his property and businesses on their way to the Canadian gold fields did not turn out exactly as he had planned. His wharf was successful, but he was forced to share his profits with outside investors because he did not have enough money to expand the operation to keep up with the flood of stampeders. By 1898, three other companies had built wharves and were competing with Moore. Moore's business managed to thrive, however, because his wharf was closest to the site where railroad tracks eventually were located.

The Moores also sold lumber from their sawmill, but they were unsuccessful in obtaining permission to construct a toll wagon road. It was George Brackett, former mayor of Minneapolis, who finally received a permit to establish a toll road. Officially opened in March 1898, the 16-foot wide wagon road stretched 15 miles from Skagway to White Pass City, where the steep climb to the summit began. The road, which was made of logs in some places and blasted rock in others, allowed travelers a shorter and easier route to the Yukon. It was used heavily for the rest of that year, but it was destined to be replaced by yet another improved method of transportation.

In May 1898, the company which became the White Pass & Yukon Route began constructing the first major commercial railroad in Alaska. Beginning in Skagway, the narrow gauge railroad wound through the twisting, narrow, rock-strewn wilderness of the White Pass. The completion of the railroad from Skagway to Bennett Lake in June 1899, and to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, a year later, secured Skagway's role as the main transportation gateway to the interior of northern Canada. Without this improved transportation method, the neighboring town of Dyea could not compete and was soon abandoned. The railroad company helped Skagway's economy at a time when the prosperity of the gold rush period was diminishing. It provided jobs and built large machine shops, an office building, hospital, residences, and even a private athletic club.

When completed in June 1900, the $10 million White Pass and Yukon Route railroad connected the geographical area outside of Alaska and northern Canada with the Klondike. Steamers from West Coast cities docked at Skagway's port where freight and passengers loaded directly onto the train. The railroad carried goods and passengers 110 miles north to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, where they transferred to sternwheel steamers on the Yukon River and continued on to the Klondike. This was a tremendous improvement over earlier transportation methods. Travelers no longer had to carry supplies on their backs or lead overburdened pack animals over the agonizing Dead Horse Trail.

The great rush to the Klondike gold fields had ended by the time the railroad was completed. Even after all the claims had been staked, however, this transportation route was still necessary to bring gold out of the Klondike and bring in supplies and equipment. Miners, surveyors, and mining engineers used the railroad and steamer route. They worked in the mines each summer, left the Klondike before the onset of harsh weather, and returned in the spring. With an efficient transportation system in place, Skagway replaced St. Michael, Alaska, as the major shipping center for freight such as zinc, lead, copper, and silver coming out of the Yukon.

The railroad provided Skagway with a narrow but stable economic base for almost 80 years after the Klondike Gold Rush ended. Today, the White Pass & Yukon Route railroad traverses the historic White Pass route, carrying tourists over a twisting rocky path through incredible scenery to an awe inspiring, snow-covered summit. This railroad is one of 20 engineering feats in the world declared an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. Since 1978, the Klondike Highway has connected Skagway to Canada's interior. A transportation gateway for commerce and tourism, Skagway serves as an example of how a frontier town survived the end of its boomtown era.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Why did Skagway become the major Alaskan point of departure to the gold fields?

2. How did Skagway continue to exist after the gold rush ended when other gold rush towns disappeared?

3. How did the railroad affect the journey to the Klondike? How might the railroad have affected the permanent residents of Skagway?

Reading 3 was adapted from Alice Cyr, "White Pass & Yukon Route Training Text for Terrific Train Guides," prepared for White Pass & Yukon Route Railway, Skagway, Alaska, 1993; Alison K. Hoagland, Buildings of Alaska (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); Ken Johnson, "White Pass & Yukon - Cold Region Triumph," APEGGA, vol. 22, no. 8, September 1994; and Roy Minter, The White Pass: Gateway to the Klondike (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 1987).

Visual Evidence

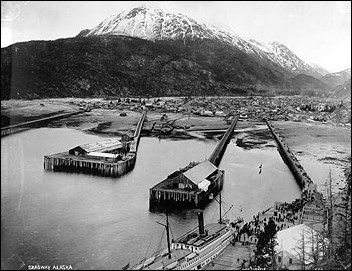

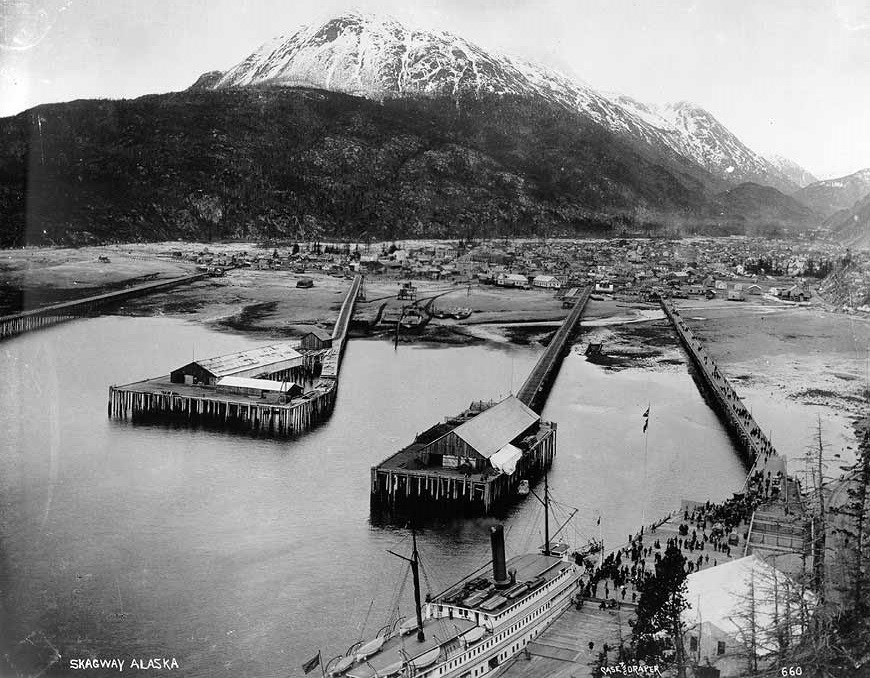

Photo 1: Skagway, Alaska, 1898.

Questions for Photo 1

1. What are your impressions of the town of Skagway and the surrounding landscape?

2. Why did the wharves extend so far from town? Why were there buildings at the ends of the wharves? What kinds of goods might have been unloaded and stored there?

3. Describe what is happening in the lower right corner of the photo.

4. If you did not know when this photo was taken, what clues might help you determine a date?

Visual Evidence

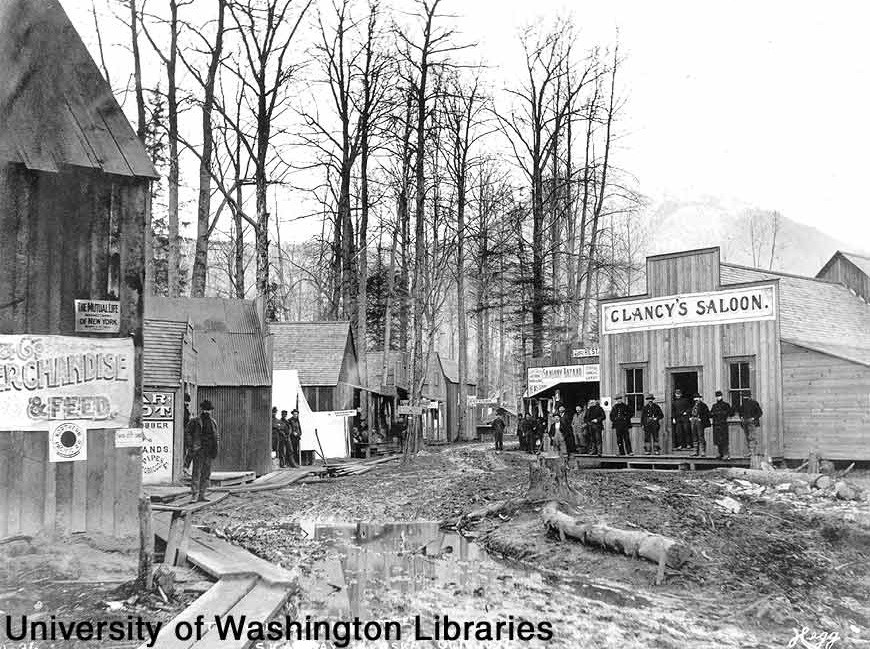

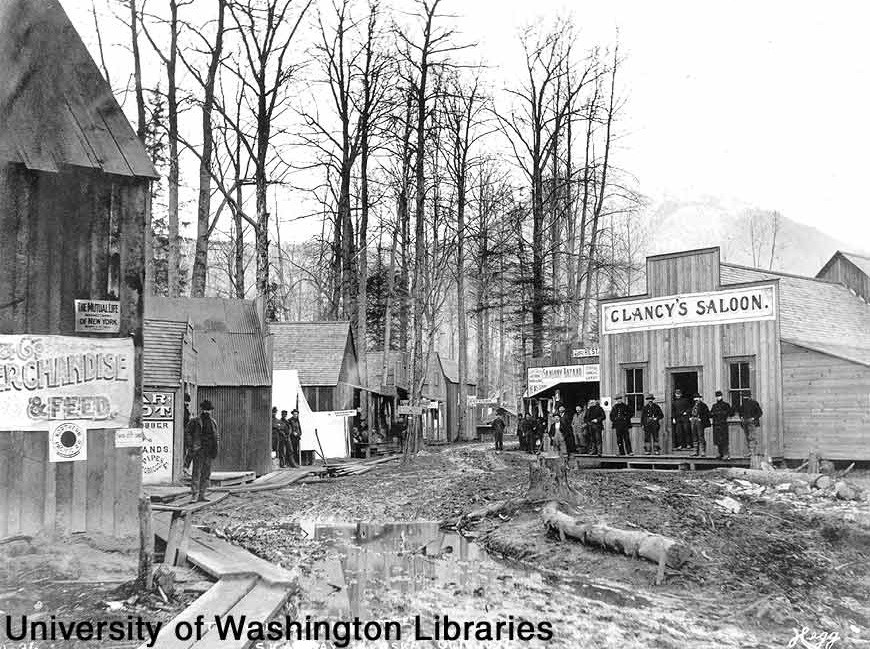

Photo 2: Trail Street in Skagway, October 1897.

Questions for Photo 2

1. Describe the buildings in this photo. How do they help tell the story of Skagway's development? How were they constructed?

2. Describe the condition of the roads and "sidewalks."

3. What does the photo suggest about the town and its inhabitants?

Visual Evidence

Drawing 1: Historic development of William Moore Cabin and Ben Moore House.

(National Park Service)

Photo 3: Ben Moore and family, Moore House, July 1904.

Questions for Drawing 1 & Photo 3

1. Match the photo of the house to the correct sketch in the drawing. Why do you think the house was built in stages?

2. What time of year was the photo taken? What does this indicate about the climate in this region?

3. What can you conclude about the lifestyle of Ben Moore and his family from studying the photo?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Golden North Hotel.

(Photo by David H. Curl, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park)

Built in 1898 by the Klondike Trading Company, this building did not house the Golden North Hotel until 1908.

Questions for Photo 4

1. Compare this building with those shown in Photo 2. What do your observations indicate about Skagway's development?

2. How does this building represent Skagway's continuing role along a transportation route to the Yukon Territory?

Visual Evidence

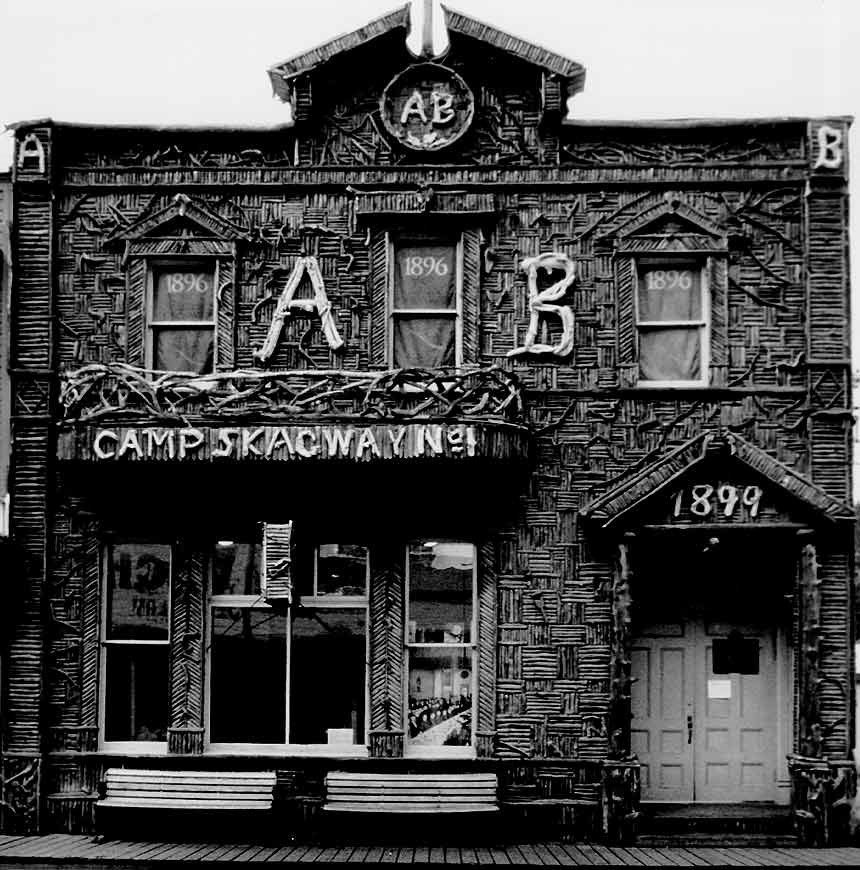

Photo 5: Arctic Brotherhood Hall.

(Photo by David H. Curl, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park)

The Arctic Brotherhood Hall, an example of rustic architecture, was built in 1899 for the Fraternal Order of the Arctic Brotherhood. Eleven men organized the fraternity on February 26, 1899, while en route from Seattle to Skagway. The organization was formed to provide mutual assistance, friendship, and social interaction in the northern communities.

Questions for Photo 5

1. Why do you think this building became one of the most photographed buildings in Alaska?

2. Describe the exterior. Why might the Brotherhood have wanted to decorate their building in this way?

3. What activities do you think might have taken place here?

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: McCabe College Building.

The McCabe College Building, built in 1899 as a Methodist school, is the only stone building in Skagway. In 1900, a new civil code allowed tax money to be used to build and maintain public schools. As a private institution, McCabe College could not compete. The building was sold to the federal government on June 1, 1901, for use as a U.S. District Courthouse.

Questions for Photo 6

1. Compare this building with those in Photo 2.

2. What do the materials and design of this building indicate about its importance? What does it indicate about Skagway's permanent population?

3. What function did this building serve other than a school? Why might it have been suitable for this purpose?

Putting It All Together

Through the following activities students will learn how the Klondike Gold Rush fits into the broader context of gold rushes in American history as well as how buildings can help reveal the stories of a community's past.

Activity 1: Gold Rushes

Have the class compile a list of gold rushes such as those that occurred in California, Nevada, and Colorado. Then ask each student to select one of these gold rushes and compare and contrast it to the Klondike Gold Rush by answering the following questions for both: Where did the gold rush take place? Who were the major people involved? How many people participated? What hardships did the miners face? What were the climate and geography of the region like? How did the prospectors get to the mines? How much gold was extracted from the mines? How did the gold rush impact the development of the surrounding area?

Possible reference books for students include Michael Gates, Gold at Fortymile Creek: Early Days in the Yukon (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1994) and Paula Mitchell Marks, Precious Dust: The True Saga of the Western Gold Rushes (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1994).

Activity 2: History and Use of Local Buildings

Have students compile a list of several buildings that collectively illustrate the development of their community over time. Divide students up into small groups and have each group choose one building to research. They should consult the library, a local museum, or historical society to find newspaper clippings, photographs, or other materials that reveal the history of the building. They may want to interview local residents about the building and about the development of the area in which the building is located. Each group should prepare an exhibit that illustrates the history of their building, including when and why it was built, building materials and style, its uses over time, and any changes over time. Share each group's work with the class and hold a discussion on how these buildings collectively tell the history of the town. Finally, have the class work together to develop a promotional brochure or walking tour of their town with photos and information about the various buildings they researched.