Last updated: March 28, 2020

Article

Silent Witnesses, Old Trees are Hiding in Our Midst

NPS

There is something about gnarly, old trees that captures the imagination. Just knowing that the living, breathing, life form in front of you has stood witness to decades and centuries of history stirs the mind. A Shawnee Native American may have leaned against it to steady himself before loosing an arrow towards a deer. William Penn could have sat underneath its crown to catch some shade during a walk. As such, it is no surprise that "old-growth" trees have inspired poetic ways of being described. Wolf trees, witness trees, sentinels - call them what you will, they are ecologically and spiritually important members of our forests today.

"You sure look big and old!"

Probably not the best way to address a fellow human, but you'd be forgiven for thinking this when ambling past large trees during a forest trek in the East. However looks can be deceiving. While some very big trees are quite venerable, not all trees or tree species grow at the same rate. Some very impressive looking trees are relatively young for their size - and vice versa. An eastern hemlock, for example, can bide its time in the understory of a forest for decades until a hole in the canopy opens up providing enough light and space for the tree to grow to full height and girth. Conversely, American sycamore trees are some of the fastest growing trees in the East. Under ideal conditions (ample sun and soil moisture) they can add 2+ feet a year in height and several inches in girth. Before it fell in 2010, the largest Sycamore tree in West Virginia (the Webster Sycamore) was likely over 350 years old. It stood more than 140 feet tall, had a crown spread of over 100 feet, and an amazing circumference of 28 feet!

A Story of Deforestation and Regrowth

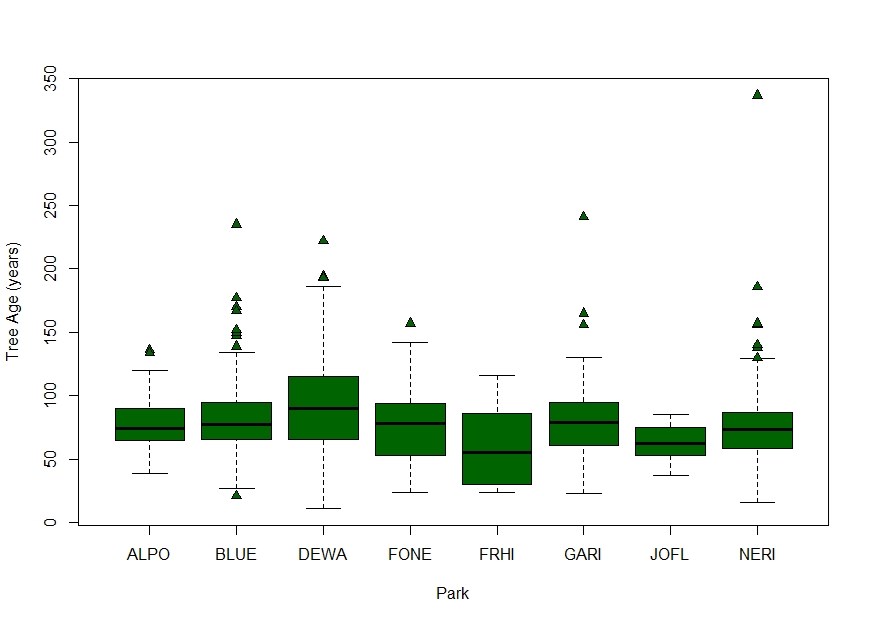

Dendrologically speaking, forests growing in the eastern U.S. are young. Most trees that have sunk their roots into the soils of Eastern Rivers and Mountains Network (ERMN) parks range from just under 50 to a little over 100 years old. But mixed among these juveniles are much older trees (see green triangles in graph below). In some cases, trees that have bore witness to a history that extends well beyond the existence of the United States itself.

NPS

Between the 1880's and 1920's, most of Pennsylvania and West Virginia were heavily logged, leaving much of the Appalachian mountains barren of trees. Throughout the twentieth century, forests began to regenerate. They eventually spread onto abandoned agricultural lands as people moved from rural to urban locations. When some of these renewed forests became national park areas during the twentieth century, almost all logging activities on them ceased.

Getting to the Core of it All

NPS

The most accurate way of confirming a tree's age is by removing an entire "tree cookie" (cross section) and counting the growth rings. The downside of this approach, as you likely can guess, is that it kills the tree in the process. Far from ideal. A much less damaging and only slightly less accurate way of aging a tree is through taking core samples. Using a heavy duty corkscrew-like device called a tree corer (or increment borer), ERMN scientists can pull small cylindrical samples of wood from a tree and count the revealed tree rings to get a good read on its age.

ERMN scientists have collected cores from two "average" looking canopy trees adjacent to every permanent longterm forest health monitoring plot in network parks. Of the 700 trees cored, over 60 of them hovered near 200 years old. This is surprising since less than 100 years ago much of this area was still largely deforested. These trees were likely passed over in previous timber harvests because they were not economically important species, were slow-growing and not large enough for harvest, or they occurred in hard to access areas (steep slope, etc.) or on a property boundary.

Cored of the Rings

The growth rings revealed by tree cores tells you much more than just the tree's age. Whole environmental histories unfold like a widesweeping historical epic. Thick growth rings speak to times of plenty, when ample sunlight and water meant that the tree could put on a lot of wood during those years. A series of tight growth rings hint to several possibilities. Maybe the tree suffered defoliation from gypsy moths or other insects, a period of drought took place, or strong competition from surrounding trees meant it had less access to sunlight and other resources. During drought years trees will often spend more energy expanding its root system in search of more water rather than putting on wood and growing new branches and leaves.

Suppression, Growth, and Release

That may sound a bit like the three progression stages of your typical biopic, but it is actually the common experience of many forest-dwelling trees.

Tom Saladyga

The amazing eastern hemlock core above is from Pipestem State Park (next to Bluestone NSR) in West Virginia. It is a perfect illustration of the trials and tribulations of a forest-grown tree's life. The core reveals that for its first 30-plus years, the hemlock had enough access to resources to grow at a steady rate. Then something happened: maybe several years of drought, insect/health issues, greater competition from other trees, or some combination of these challenges. For the next 25 years or so it grew slowly, very slowly some years. Then its fortunes changed again, and it suddenly began putting on a lot of wood. The tree may have grown taller than all those around it, or the surrounding trees were removed by a storm or logging. This pattern of restricted growth and release continues throughout the tree's life. Using historic climate data and tree core samples like this one, scientists can accurately reconstruct a region's environmental history.

Unwieldy Wolves, Titanic Tulips, Behemoth Buckeyes, and Outsized Oaks

In contrast to those relatively slim specimens, New River Gorge NR and Carnifex Ferry Battlefield State Park (just adjacent to Gauley River NRA) shelter about 40 acres of large, old-growth trees between them. Dozens of 2-foot diameter or more chinquapin oaks, northern red oaks, bitternut hickories, hemlocks, tulip trees, buckeyes, and other species show old-growth characteristics. Many reach well into the 100-200 year old (or more) range.

Some trees in these forests are almost impossible not to notice. They are large, with wide-spreading crowns and stand in stark contrast to much younger and smaller trees surrounding them. Sometimes referred to as "wolf trees", they speak to a time when they may have been the only tree in the immediate area - standing like a lone wolf. Often, wolf trees are over 150 years old and a different species then their smaller neighbors. The defining characteristic of a wolf is its wide-spreading structure. The ample real estate it provides contains highly valuable and often locally rare wildlife habitat with nooks, crannies, and tree cavities galore.

These and other generational trees are just waiting for you to go find them in your nearby national park or local forest. So on your next walk along your favorite trail, realize you could be walking amongst trees that have seen a history that extends across centuries.

For More Information

ERMN tracks forest health in a series of 360 permanent monitoring plots set up in eight national parks. Information on tree health, forest regeneration, plant diversity, invasive species, and more is collected.

To learn more, see ERMN's vegetation and soils monitoring page on their website at www.nps.gov/im/ermn/vegetation-soils.htm.

Tags

- allegheny portage railroad national historic site

- bluestone national scenic river

- delaware water gap national recreation area

- fort necessity national battlefield

- friendship hill national historic site

- gauley river national recreation area

- johnstown flood national memorial

- new river gorge national park & preserve

- ermn

- forest ecology

- ecology

- old growth

- tree

- tree core

- forests

- science

- inventory and monitoring

- natural resources

- vegetation