Last updated: July 20, 2022

Article

Shenandoah's Civil War Connection

June 18, 1862-Leaving the Shenandoah Valley: Jackson Crosses the Blue Ridge Mountains through Browns Gap

The Blue Ridge MountainsThe Blue Ridge Mountains running along the East side of the Shenandoah Valley make up the core of Shenandoah National Park where Skyline Drive runs along their crest. Today most visitors to the park travel along at least a portion of Skyline Drive, from whence they encounter stunning vistas of the Shenandoah Valley from numerous viewpoints along the drive. What visitors may not realize is that they are driving along one of the most significant tools the Confederacy utilized during the American Civil War.

Throughout the four years of the Civil War (1861-1865), Confederate armies frequently used the Blue Ridge Mountains as a natural screen to conceal the movement of troops from Union forces. Because of the southwest-northeast orientation of the Shenandoah Valley west of the Blue Ridge, Confederate armies marching down the Valley naturally moved toward a position from whence they could threaten the northern cities of Washington and Baltimore, while Union armies marching up the Valley were forced to move farther away from the Confederate capital of Richmond.

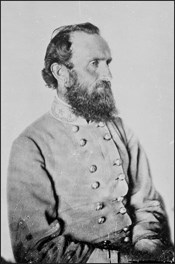

In addition to shielding troop movements, the Blue Ridge Mountains also contained passes and roads that passed directly through what is now Shenandoah National Park. The larger passes, such as Rockfish and Thornton Gaps, were used throughout the war by both armies, but Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson was uniquely gifted in utilizing the lesser known passes to conceal his troop movements from prying eyes, allowing him to move troops from the Valley into the piedmont without the Federals knowing he was doing so.

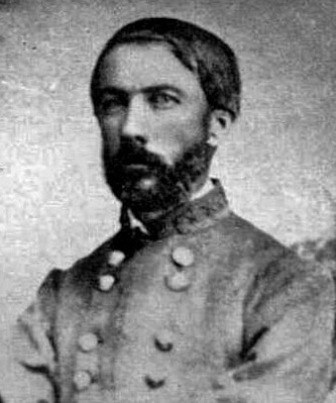

Jackson is unquestionably one of the most legendary and well known commanders of the American Civil War. Much of that reputation is due to the success and skill he demonstrated not only on the field of battle, but also in the manner in which he used the mountains to conceal the movement of his troops during his 1862 campaign in the Shenandoah Valley.

In the years preceding the war Jackson had made his home in Lexington, VA and developed a deep connection to the Shenandoah Valley and the mountains surrounding it.

As the war progressed Jackson rose to command a brigade that was composed almost entirely of men from the Shenandoah Valley and the surrounding mountains. When Jackson was further elevated to the rank of General and given command of an independent force, it was these men, who came to be known as the "stonewall brigade" who formed the core of Jackson's army during the Valley Campaign of 1862.

Between the end of March and mid-June Jackson and his men marched more than 500 miles, fought six pitched battles, and frequently engaged union troops in smaller skirmishes around the valley, often on ground that his men had grown up on.

Skyline Drive not only runs along the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains, but also provides views that include the sites of the six major battles that made up the 1862 Valley Campaign.

1. Kernstown (March 23)

2. McDowell (May 8)

3. Front Royal (May 23)

4. 1st Winchester (May 25)

5. Cross Keys (June 8)

6. Port Republic (June 9)

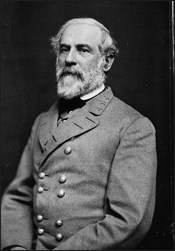

In recognition of Jackson's success at Cross Keys and Port Republic Gen. Robert E. Lee wrote to Jackson from Richmond on June 11th:

"Your recent successes have been the cause of the liveliest joy in this army as well as in the country. The admiration excited by your skill and boldness has been constantly mingled with solicitude for your situation."

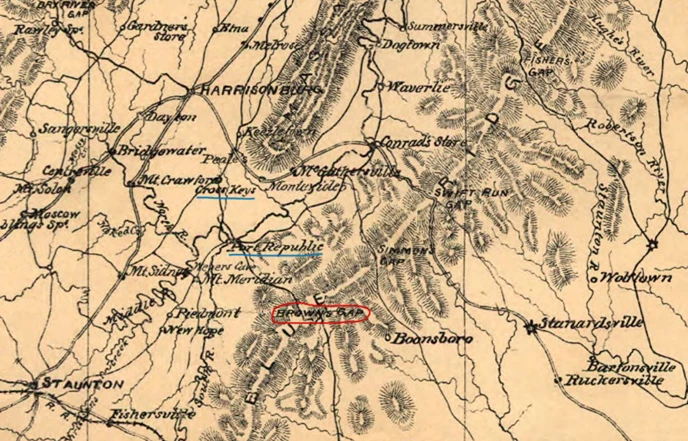

Following his victories at Cross Keys and Port Republic, Jackson pulled his troops out of the valley into the Blue Ridge Mountains and ensconced his army at Brown's Gap where he remained for three days. While there Jackson sent messages to Richmond requesting that his force be increased to 40,000 men so that he might push offensively down the Valley and across the Potomac, in order to drive the Federal troops out for good and directly threaten Washington.

Jackson's Valley campaign had already delayed Union Gen. George McClellan's attack on Richmond by drawing the 40,000 men under Gen. Irvin McDowell away from Richmond to the Shenandoah Valley. Believing that he could best keep Union forces away from McClellan's efforts against Richmond by exciting fears for the safety of Washington, Lee sent Jackson 14,000 reinforcements by rail for this purpose.

As they were taken from the Valley toward Richmond Federal prisoners met these reinforcements in passing, and when paroled shortly thereafter, carried the news to Washington, where it had exactly the effect that Lee and Jackson desired. After resting for three days, in Jackson's own words, on June 12th, the troops moved down from the mountains, "recrossed South River and encamped near Weyer's Cave." They were soon joined there by six of the regiments sent by Lee, with the remainder of the reinforcements on their way to Staunton.

Union Retreat

In the aftermath of the Battles of Cross Keys and Port Republic both Union Gen. John Frémont (whom Jackson had defeated at Cross Keys) and Gen. James Shields (whom Jackson had defeated at Port Republic) pulled back down the valley away from Jackson.

When Jackson returned to the valley on June 12, he sent cavalry out in front of his men, who spread intelligence that Jackson, with 50,000 men or more, would soon again march down the Valley to drive the Federals out entirely. These tactics were so successful, that not only did both Union armies continue to retreat, but on June 12 Frémont telegraphed Washington that "Jackson is heavily reinforced and is advancing." One week later, on the 19th he sent another message to Washington claiming, "No doubt another immediate movement down the Valley is intended, with a force of 30,000 or more."

These messages and the movement of reinforcements to Jackson had the desired effect of both deterring Union troops in the Valley from further action, and redirecting reinforcements intended for McClellan's offensive move against Richmond.

As a result of this success, four days later on June 16, General Lee wrote to Jackson, suggesting that he and his men march from the Shenandoah Valley to assist in the relief of Richmond, by attacking the relatively unprotected right flank of McClellan's army, north of the Chickahominy River.

Marching through Brown's Gap

Shortly after midnight, in the early hours of June 18, Jackson and his men left their position at Weyer's Cave and began the 120 mile march to Richmond. The route that Jackson took on his secret march through the night of June 17-18 followed the old Browns Gap Turnpike across the Blue Ridge Mountains, past their camp of a week earlier, and down toward Richmond.As Jackson himself records, "The army remained near Weyer's Cave until the 17th, when, in obedience to instructions from the commanding general of the department, it moved toward Richmond."

Construction of the road they took had begun in 1805 by Brightberry Brown and William Jarman. Commonly known as "Brown's Turnpike," this road had become an important crossing through the mountains by the time of the Civil War and was utilized effectively by Confederate forces on several occasions.

After defeating all three Union armies in the region and pulling additional reinforcements away from Richmond, Jackson successfully departed from the Shenandoah Valley and joined Lee as he prepared to launch an attack on McClellan's exposed right wing. His use of the Blue Ridge Mountains to both conceal his movements and provide passage into the piedmont was so successful that, on June 28, ten days after Jackson had left the valley, when he and his men were actually fighting McClellan in the Seven Days Battle, Union General Nathaniel Banks (whom Jackson had defeated at the First Battle of Winchester on May 25) still believed "Jackson meditates an attack in the valley." The mountains had played a key role in the success of the Confederate armies once again.

November 28, 1862-Marching to Destiny: Jackson's use of the Blue Ridge Mountains to screen his movement to Fredericksburg

The Blue Ridge Mountains as a Confederate AllyJackson made it clear that this talent for using the Blue Ridge Mountains to his strategic advantage was not limited to a single campaign when he exhibited the same aptitude five months later.

The Road from Antietam

On September 17, 1862 the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and Union Army of the Potomac engaged each other at the Battle of Antietam, on what remains the single bloodiest day in American history.

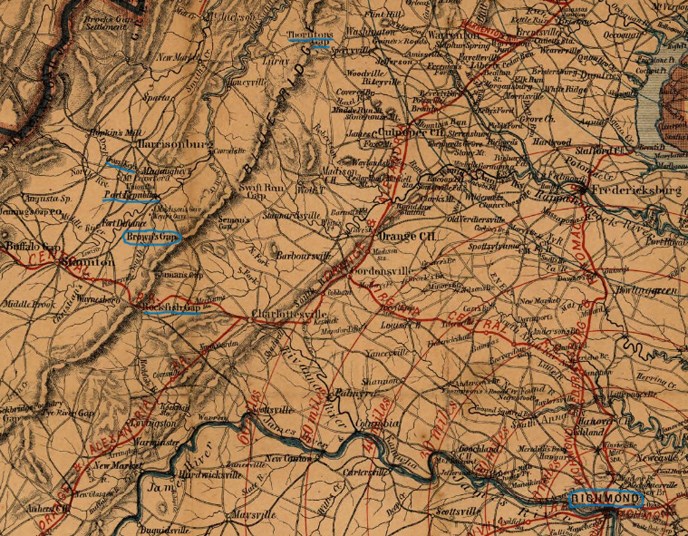

The following day Confederate commander Robert E. Lee decided to pull his army off the field of battle and retreat across the Potomac River into Virginia. He then decided to split the army in two, sending the newly designated II Corps under Jackson up the Shenandoah Valley while he and the remainder of the army moved south where they spent the next two months regrouping in the piedmont region between Culpeper and Fredericksburg.

While Jackson and his Corps rested unopposed in the valley, Lee kept eye on the Union Army of the Potomac. On November 17 the Right Grand Division of this army, a third of the total force now commanded by Ambrose Burnside, reached the ground just across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg, VA.

The next day, on November 18, Lee began moving the 40,000 men under his direct command to block Burnside's advance and sent this message to Jackson:

This simple message was all Jackson needed to take his corps on a route he had planned out in case the need arose. Whereas in June he had used Browns Gap southeast of Harrisonburg to move his forces to Richmond, now Jackson wished to pass through the mountains further north."I think it would be advisable to put some of your divisions in motion across the mountains."

Once Hill began to move the rest of Jackson's corps soon followed. Captain James Cooper Nisbet recorded that, "on November 21st we bade the valley…goodbye…and commenced our march down the valley. We proceeded through Winchester to New Market, where the head of the column turned toward the Blue Ridge."

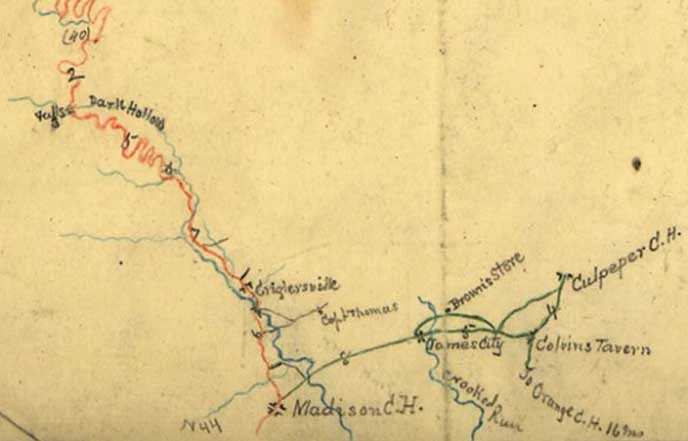

The Gordonsville New Market Turnpike

The route ordered by Jackson meant that Hill's division with the rest of Jackson's Corps behind it, would cross the mountains via Fishers Gap on the Gordonsville Newmarket Turnpike. This road had only been completed nine years earlier after the state chartered the Blue Ridge Turnpike Company for the purpose of constructing a road through the gap following the path of the Rose River.* Finished in the spring of 1853, the Turnpike offered a much more direct and better concealed passage for Jackson to reach Fredericksburg and assist Lee. Jackson knew of the route because of the devoted work of his chief cartographer, Jedediah Hotchkiss.

*This river had originally been referred to as "Row's River" after George Row who owned property near its head, but had subsequently morphed into "Rose River."

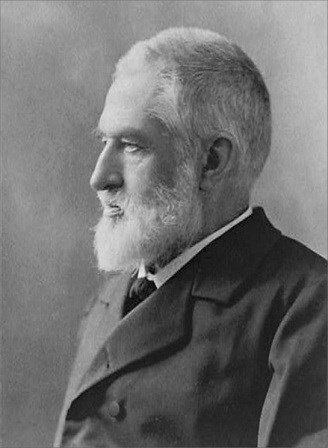

Jedediah Hotchkiss had requested service with General Jackson as a topographic engineer (map maker) when he responded to Virginia Governor Letcher's call for militia on March 10, 1862. Jackson had quickly taken advantage of Hotchkiss, telling him on March 26 that he wanted Hotchkiss to make him "a map of the Valley, from Harpers Ferry to Lexington, showing all the points of offense and defense in those places."

"It was the dedicated work of Hotchkiss that provided Jackson with the information he needed during the Valley Campaign and subsequent movements. In early November, anticipating the need for a movement to join Lee in the East, Jackson sent Hotchkiss out once again, this time to personally travel along the Gordonsville Newmarket Turnpike to survey it for use as a potential route for the movement of his corps. On November 12, 1862 Hotchkiss wrote to his wife Sara of the journey:

"Monday was a fine day, and I had a nice ride across the Blue Ridge, by the crookedest road I have ever seen -- 19 miles across -- but the road is a fine one."

In Jackson's order to Hill he refers to the pass through the mountains as "Fishers Gap," which is the same name by which the park designates the gap today. About three miles south of Fishers Gap visitors to the park will find "Milam Gap." Today these two names clearly refer to two different gaps on Skyline Drive, but this was not always the case.

Fishers Gap takes its name from Stephen Fisher who received a Northern Neck Land Grant for 216 acres in the region on August 4, 1778. His grant describes the land it includes as: "a certain Tract of Waste & ungranted land near Milam's Pass on the Blue Ridge in Culpeper and Shenandoah Counties." In the grant through which Fisher gained the land we see a reference to "Milam's Pass." When this same parcel of land was sold to Isaac N. Long, John E. Koontz and A. J. Huffman more than 200 years later, on July 25 1894, it was referred to in the same way: "The tract of 216 acres more or less of land lying in the counties of Madison & Page near what is known as Milam's pass or Milam's gap on the Blue Ridge Mountains."

Thus it appears that what we now know as Fishers Gap was earlier referred to as Milam's Pass and Milam's Gap in land grants and surveys. Even Hotchkiss, who referred to it as Fishers Gap when communicating with Jackson, labeled it as Milam's Gap on his maps.

All such confusion was sorted out when Isaac N. Long sold the land to the Virginia State Commission on Conservation on July 8, 1931, who then turned the land over to the National Park Service to be part of Shenandoah National Park.

Seeing the arrival of Burnside's entire army north of the Rappahannock River in the vicinity of Fredericksburg, Lee decided to send a second message to Jackson on November 23. In this message, Lee stated that he did not see "what military effect can be produced by the continuance of your corps in the valley. I wish you would move east of the Blue Ridge."

On November 28, 1862 Hill's division led the way in crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Staunton Spectator records that:

Roots in the Mountains"The army was marching by brigades, each brigade followed by its own artillery and wagon train; they stretching for miles and miles along the turnpike, up the mountain side, and far across the Page Valley to the Massanutten range. The troops and trains winding the turns of the grade up the mountain were at times all in sight and seemed moving in every possible direction, 'In wondering mazes lost'."

In addition to preserving the routes that Jackson used to move across the mountains in 1862, Shenandoah also preserves the land that many of Jackson's men called home. The "stonewall" brigade that Jackson originally commanded at the First Battle of Manassas, and which remained under his command until his death in 1863, was made up almost entirely of men from the Shenandoah Valley and surrounding mountains. Several other regiments in Jackson's corps contained men whose homes were located in the land now preserved by Shenandoah National Park.

Two such men, John Weakley and Layton Sisk, served in the 10th Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which was made up almost entirely of men from the Shenandoah Valley and Blue Ridge Mountains.