Abraham Lincoln was having a bad day on September 11, 1862. Confederates had crossed the Mason-Dixon Line in advance of a full-scale Southern invasion of Pennsylvania. Another Rebel army had pulled within five miles of Cincinnati, threatening Ohio's largest city and its biggest center of commerce. Newspapers across the North were announcing Confederate peace terms. The Confederate Congress had just adopted an aggressive war of invasion of U.S. soil as its new national policy. And a delegation of Chicago ministers arrived in Washington to demand immediate and unconditional emancipation of slaves. The governor of Pennsylvania thundered the loudest to President Lincoln. "Their destination is Harrisburg or Philadelphia," exploded Governor Andrew Curtin. "The time for decided action by the National Government has arrived. What may we expect?" Curtin then dispatched an urgent plea to the mayor of Philadelphia - the nation's second largest city. "We need every man immediately. Stir up your population tonight. . . . No time can be lost in massing a force along the Susquehanna [River] to defend the State, and your city. Arouse every man possible."

"Would my word free the slaves, when I cannot even enforce the Constitution in the Rebel States?" President Lincoln to the Chicago ministerial delegation

Tides Changing

Library of Congress

September had opened badly for President Lincoln. One of his armies had just been defeated in the Battle of Second Bull Run. It had been forced to retreat behind the defenses of Washington. Lincoln discovered his army demoralized, disorganized, and without solid leadership - creating a vacuum that permitted Confederate invasion of Northern territory for the first time. The Southern invasion, combined with a nearly disgraced U.S. military, weakened the president's opportunity for emancipation. "What good would a proclamation of emancipation from me do, especially as we are now situated?" President Lincoln asked the Chicago ministerial delegation. "I do not want to issue a document that the whole world will see must necessarily be inoperative . . . Would my word free the slaves, when I cannot even enforce the Constitution in the Rebel States?"

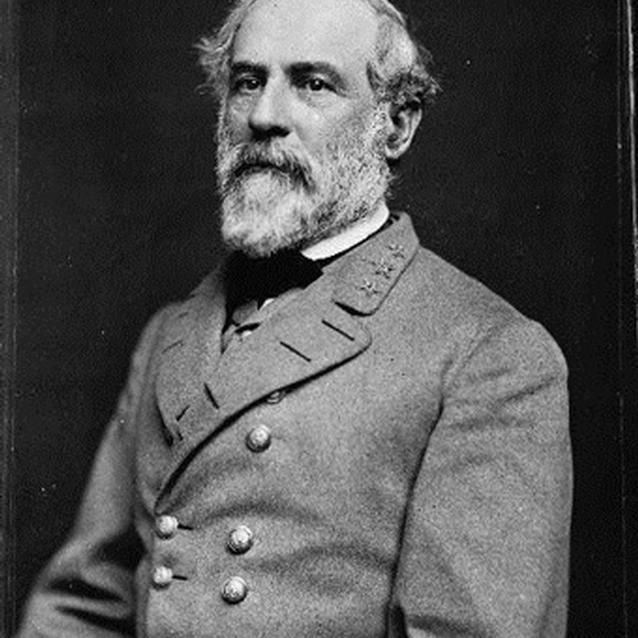

Robert E. Lee was having a good day on September 11. The Confederate commander of the Army of Northern Virginia had arrived in Hagerstown, less than six miles from the Pennsylvania border. Confederate Thanksgiving Day was one week away (September 18), and Lee expected that his army would be celebrating it somewhere in the Quaker State. General Lee sensed history was about to change. Three days earlier, from his temporary bivouac at Frederick, he informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis: "The present position of affairs, in my opinion, places it in the power of the Government of the Confederate States to propose with propriety to that of the United States the recognition of our independence."

Lee knew he was in a position to control the destiny of the Confederacy, and to influence the future of the United States. "The rejection of this offer would prove to the country that the responsibility of the continuance of the war does not rest upon us, but that the power in the United States elects to prosecute it for purposes of their own."

Lee in Control

Library of Congress

Lee was aware his actions could affect the 1862 Congressional elections - only weeks away. "The proposal of peace would enable the people of the United States to determine at their coming elections whether they will support those who favor a prolongation of the war, or those who wish to bring it to a termination." The future of the United States appeared, at this moment, in the hands of Robert E. Lee. The South dramatically had changed the course of the war during the summer of 1862. At the end of June, it appeared the Confederate capital at Richmond would be captured. Ten weeks later, following successful battles and skillful maneuvering by Rebel armies, Washington and Baltimore and Cincinnati became the threatened cities, and Pennsylvania and Ohio the panicked states.

This turnabout was remarkable. The military prowess of the Confederacy, in fact, earned European attention. "The Federal Government is brought to the verge of ruin," observed The London Times. "That word may be used when the Executive Government of the North is no longer safe in its capital." Since the war's inception, the Confederacy had sought diplomatic recognition or European intervention. The invasion of the North, coupled with continued Confederate battlefield victories, made this dream more plausible. Maryland offered a tempting prize as a launch pad for the South's invasion. In Maryland Lee could threaten Washington or Baltimore, the country's fourth largest city. The Confederates also came to "liberate" the state from what they considered the oppression and despotism of the Lincoln government. Maryland was a slave state, and it was the first Southern state occupied by U. S. forces. Maryland's legislators were placed under house arrest to ensure they could not vote for secession, and various sections of the Bill of Rights had been suspended.

Lee's Army

Library of Congress

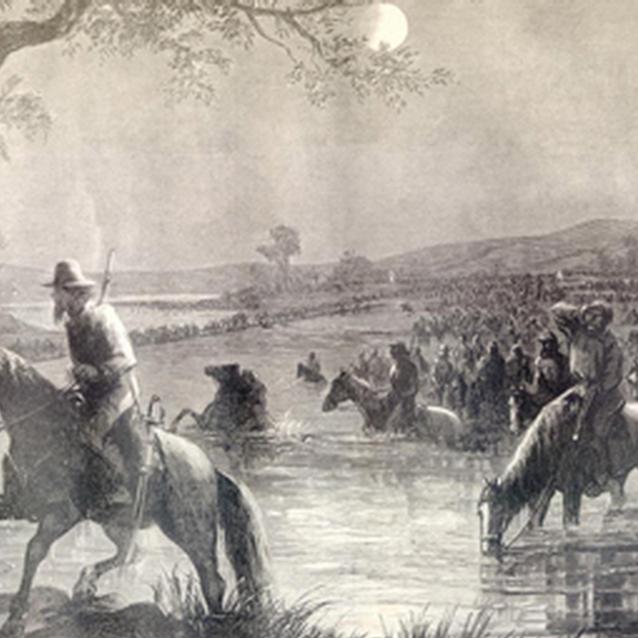

When General Lee and his army arrived at Frederick at the end of September's first week, the guessing began almost immediately. Where were the Confederates going? What was the Rebel target? How far into the United States would the Rebels advance? No one in the North knew his intentions. Lee magnified the mystery with an extended halt at Frederick. Here he rested his men and he purchased food, supplies, and clothing. "The army is not properly equipped for an invasion," Lee informed President Davis. "It lacks much of the material of war, is feeble in transportation, the animals much reduced, and the men are poorly provided with clothes, and in thousands of instances are destitute of shoes."

The Baltimore reporter encountered six young men who came to Frederick to enlist, "but after seeing and smelling" the Confederate army, concluded to return home. "I have never seen a mass of such filthy strong-smelling men. Three of them in a room would make it unbearable, and when marching in column along the street the smell from them was most offensive."

While at Frederick, Lee had one eye on the Union army about Washington, and the other starring at Harpers Ferry. Almost 14,000 U. S. soldiers occupied the Shenandoah Valley, menacing Lee's line of supply from Virginia. To rid this problem, Lee issued Special Orders 191 on September 9, ordering Stonewall Jackson to march two-thirds of the army toward Harpers Ferry to eliminate the Yankees pestering the Confederate rear.

The operation commenced the next day, and the army split into four columns. Three advanced toward the Ferry to seize the three mountains surrounding the town. Lee led the fourth column to Hagerstown, where he awaited news on Stonewall's mission.

Battle Underway

Library of Congress

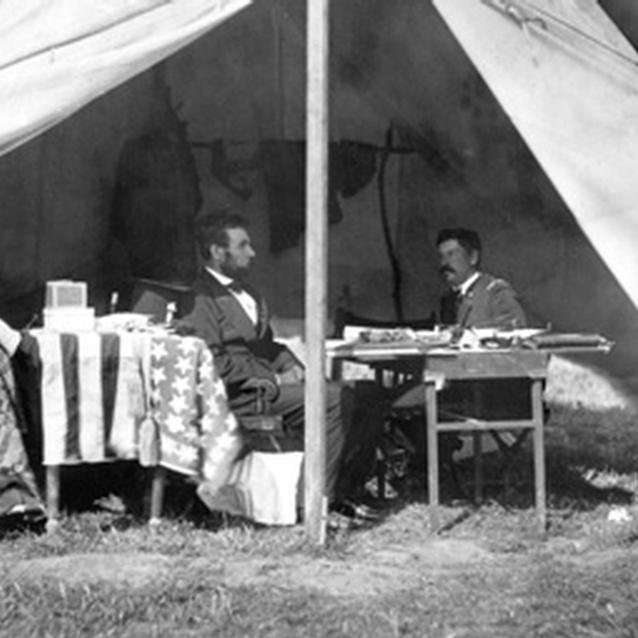

Lee established a time table for Jackson, instructing him to have the Harpers Ferry operation underway by September 12. But Jackson was late. The investment did not commence until the 13th, and this delay proved disastrous for Lee's invasion. Meanwhile, the Union Army of the Potomac had moved from Washington and reached Frederick. Here its leader, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, was presented with one of the greatest gifts in military history - a lost copy of Lee's Special Orders 191 came into his hands on September 13. "I have all the plans of the Rebels," he notified President Lincoln, "and will catch them in their own trap."

McClellan then devised a plan "to cut the enemy in two and beat him in detail." He would send a rescue column to Harpers Ferry to relieve the besieged garrison. At the same time, he would rush another portion of his army over South Mountain and toward the Potomac River to cut off Lee's line of retreat from Hagerstown.

General Lee knew something was wrong. From his position at Hagerstown, he received alarming reports of the Union army moving aggressively toward South Mountain. Lee could not permit the Yankees to cross that mountain. The enemy could endanger the Harpers Ferry operation, and with his army divided and scattered, McClellan could threaten the very existence of the Confederate army. Lee turned away from Pennsylvania - at least for the moment, and he hurried back toward South Mountain. Combat raged on South Mountain on Sunday, September 14, as the Confederates desperately battled to plug the passes. That night, with Jackson still not successful at Harpers Ferry despite a tightening noose and a day of heavy bombardment, Lee determined to retreat. "The day has gone against us. This army will go by way of Sharpsburg and cross the river."

But while halted near the Antietam Creek, Lee finally received some good news from Jackson. "Through God's blessing, I believe Harpers Ferry and its garrison will surrender on the morrow [the 15th]." Bolstered by this hopeful information, Lee decided to halt at Sharpsburg and await Stonewall's results. When he learned that Jackson, indeed, had forced the capitulation of Harpers Ferry, the Confederate general determined to reunite the army along the banks of the Antietam

Lee's Fight

Library of Congress

As Lee waited, Pennsylvania continued to beckon. The Quaker State was only one day's march from Sharpsburg. If Jackson and two-thirds of his army could join him quickly, Lee could continue the invasion. General McClellan, however, had other plans. On September 16, he moved a portion of his army across the Antietam, seizing Lee's only route of advance northward. With this option removed, Lee could either retreat back home into Virginia or stand and fight.

Lee chose to fight. Too much was riding on the Confederate invasion to return home without a victory on Northern soil. Lee's decision brought great risk to his army, as he was outnumbered, and not all of his men had rejoined him from Harpers Ferry. Could he withstand attack without collapsing? The Battle of Antietam raged for more than 12 hours on September 17. Unknown places like the Dunker Church, The Cornfield, The West Woods, Bloody Lane, and Burnside Bridge soon became branded into military history forever. Lee's lines buckled and bent, but they never completely broke; and at the end of American's bloodiest single day battle, the Confederates remained in Maryland.

Not for long, however. Lee dared McClellan to attack him on Confederate Thanksgiving Day (September 18), but that night, he withdrew into Virginia. He intended to continue the invasion, however, by re-crossing the Potomac at Williamsport, but McClellan foiled this plan when he seized that position. Lee also became concerned when the Yankees crossed the river in his rear, resulting in the Battle of Shepherdstown on September 20, where Stonewall Jackson's men swatted the Federals back across the Potomac. This action concluded the invasion.

Safety

Library of Congress

Washington was safe. Baltimore was secure. Pennsylvania no longer was quaking. Cincinnati was saved. Ohio was relieved. The Union trumpeted its victories at South Mountain and Antietam. The invasions had ended. Lincoln had triumphed. The turnabout had been remarkable - this time in favor of the United States. Never again would the Confederacy have a better opportunity for independence. Never again would the South have better prospects for peace on its terms. Never again would the European powers offer legitimacy to the Confederacy. Even the elections failed to turn against Northern proponents of the war.

And for Abraham Lincoln, the moment had arrived. Armed with recent battlefield victories and the termination of Rebel invasion, the president issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation only five days after Antietam.

The war, and the nation, had changed forever.

Last updated: July 11, 2019