That morning that I woke up and...it was very misty and the Alabama National Guard had been federalized to protect us on this walk....This was my 15th birthday. I have never in my life been as frightened as I was on that day. Lynda Lowery

Pettus, Peter, photographer; Library of Congress: LC-DIG-ppmsca-08102

Until 1965, counties in Alabama used preventive measures in order to prevent African-Americans from registering to vote. Because of this, only 2% percent of the African-American population of Dallas County at that time was able to vote and 0% in Lowndes County. However, civil rights activists began to protest in Selma in order to bring attention to this injustice. These protests were often met by violence from the local sheriff's department, leaving many wondering what was going to happen next.

The First March: Bloody Sunday

nps

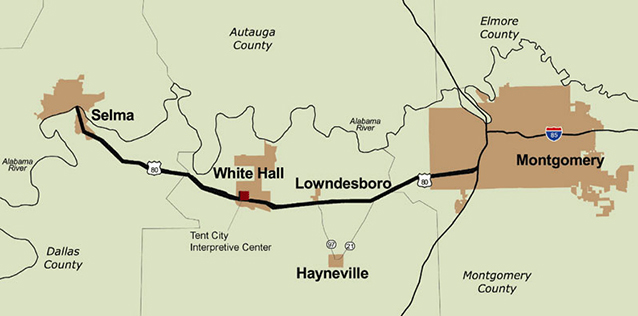

On March 7, approximately 600 non-violent protestors, the vast majority being African-American, departed from Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in Selma with the intent on marching 54-miles to Montgomery, as a memorial to Jimmy Lee Jackson and to protest for voter's rights. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, they were met by a column of State Troopers and local volunteer officers of the local sheriff's department who blocked their path.

The non-violent protesters were told by Maj. John Cloud that they had two minutes to return back to their church and homes. In less than the time allotted, they were attacked by the Law Enforcement Officers with nightsticks and teargas. According to several reports, at least 50 protestors required hospital treatment. The brutality that was displayed on this day was captured by the media; however, the media was held back as the protesters retreated, where the violence continued for some time.

The attack caused outrage around the country, and March 7 became known as "Bloody Sunday".

The Second March: Turnaround Tuesday

Two days later on March 9, Martin Luther King, Jr., led a "symbolic" march to the bridge. This time they decided to turn back and not risk a violent confrontation. The Reverend Jim MacDonell remembered the day in his oral history:

And it took about an hour to get everybody lined up and start the march out of town because the Edmund Pettus Bridge is about a half mile out of town. And, of course, we walked across the bridge and over the top of the bridge and down the other side. As we came down the highway, we looked across the highway, and there as far as we could see were flashing lights and police cars and helmeted troopers carrying shotguns blocking the way. It was very ominus. Dr. King got on a bullhorn, which he borrowed from Major Lingo of the Alabama police, and he said, “Folks, we’re going to have to stop. And we have been assured that we can kneel for a moment of prayer, which will be led by the right Reverend John Wesley Lord, the Methodist bishop of Washington D.C. And so we all, 2000 people going back up over the bridge, all knelt down on the pavement. I was up only about 10 feet from the front. And as I was kneeling there, all of a sudden I heard, “Oh Lord our God…” And it was not John Welsley Lord, it was my Presbyterian friend, the New York Abner Presbyterian Church. And he prayed. That was dear Dr. Docherty. He was a great man. He prayed for the people of Selma. He prayed for the governor of Alabama. He prayed for the troopers. He prayed for peace and reconciliation. It was very moving. We were very emotional. But they were the right, the right words were said."

That evening, three Unitarian ministers who had traveled to Selma in order to join the protest were attacked by a group of white hooligans. On March 11, Rev. James Reeb, died from his injuries.

Then civil rights leaders sought court protection for a third, full-scale march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery. Federal District Court Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., weighed the right of mobility against the right to march and ruled in favor of the demonstrators. "The law is clear that the right to petition one's government for the redress of grievances may be exercised in large groups...," said Judge Johnson, "and these rights may be exercised by marching, even along public highways."

The Third March

nps

The civil rights protestors sought and received an injunction for a third march, which was granted by Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. on March 17. On Sunday, March 21, about 3,200 marchers set out for Montgomery, walking 12 miles a day and sleeping in fields. By the time they reached the capitol on Thursday, March 25, they were 25,000-strong. Only this third march, which began on March 21, reached the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery.

Less than five months after the last of the three marches, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965--the best possible redress of grievances.

Last updated: April 4, 2016