Last updated: October 12, 2018

Article

Segregation and Desegregation at Shenandoah National Park

NPS Archives

Laboratory for Change

by Reed Engle, Cultural Resource Specialist, 1994-2008

This article first appeared in Resource Management Newsletter, January 1996.

On November 30, 1932, Arno B. Cammerer, Deputy Director of the National Park Service, hand-wrote “Provision for colored guests” on a typed memorandum about the development of concession facilities in the proposed Shenandoah National Park. Cammerer wrote this note to Horace Albright, Director of the National Park Service. Three years prior to Shenandoah’s official establishment, park managers were laying the groundwork for an official “separate, but equal” policy.

From 1933 to 1936 no concession facilities were developed on Skyline Drive since Congressional authority had not been given, although private enterprises were scattered around Shenandoah. These included Skyland Resort, operated by George Freeman Pollock, the Spotswood Tea Room at Swift Run Gap operated by Ralph Mims, and the Panorama Restaurant operated by Williams and Cheatham. An initial effort at facilities development by a consortium of businessmen known as Virginia Hosts, Inc. went through several evolutions only to wither. In October 1936, a Richmond group headed by Mason Manghum, Virginia Sky-Line Company, expressed interest in concessions operations. Virginia Sky-line Company’s concessionaire proposal rapidly was accepted by the government in bids opened on January 15, 1937.

By the following summer, Virginia Sky-Line Company had laid out preliminary plans for the development of facilities that included a new lodge at Dickey Ridge, two large public buildings at Skyland, a gas station, visitor cabins and a lodge at Big Meadows, and “a development for colored people” at Lewis Mountain, including a campground, smaller lodge, and cabins.

As these plans were being formulated, Harold L. Ickes, Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Secretary of the Interior, wrote in his diary:

... my stand on the Negro question is well known. I have been in the advance of every other member of the Cabinet, and the Negroes recognize this.... It begins to look as if real justice and opportunity for the Negro at long last might begin to come to him at the hands of the Democratic party, which Negroes have scorned... until they swung over to Roosevelt in large numbers in 1932...

Ickes' beliefs, however, were not reflected in the stated policies of the National Park Service in 1936 concerning segregation in Virginia’s parks:

The program of development of facilities... for the accommodation and convenience of the visiting public contemplates…separate facilities for white and colored people to the extent only as is necessary to conform with the generally accepted customs long established in Virginia…To render the most satisfactory service to white and colored visitors it is generally recognized that separate rest rooms, cabin colonies and picnic ground facilities should be provided.

Shenandoah's first Superintendent, J. Ralph Lassiter, former Chief Engineer for Park Development and a Virginia native, followed the Service policy, noting in early 1937 that a "proposed colored picnic grounds at Lewis Mountain" was in the park master plan. By mid-summer, however, he was prodded by the Washington office:

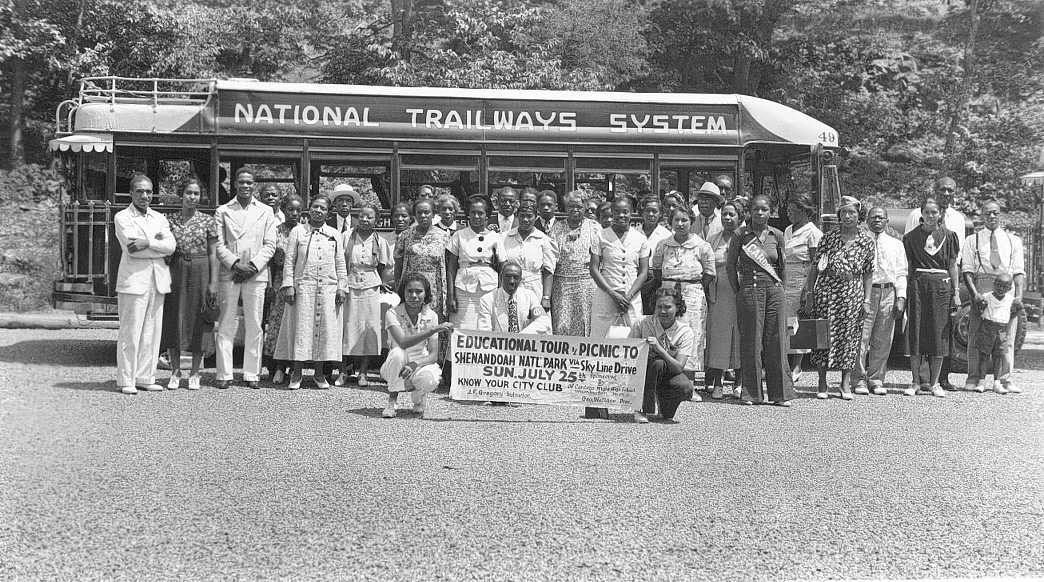

There is a growing demand for picnic areas for colored people…Two bus loads are going up tomorrow and they have to be fitted into camping places for white people. This is not a good condition…

It was soon decided that the concessionaire would develop the picnic area, campground, cabins, and restaurant at Lewis Mountain, a departure from precedent at other areas in which the CCC had constructed the picnic and campground facilities to be managed by the National Park Service.

By June, 1938, the Superintendent reported that the picnic area had been graded, fireplaces soon were to be built, and the comfort station was almost complete. Virginia Sky-Line Company was reviewing preliminary architectural drawings by Marcellus Wright for the new lodge and cabins.

As Superintendent Lassiter attempted to satisfy and expedite the existing Service policy, the Department of the Interior solicitor suggested to the Secretary of the Interior that "segregation of the races as now practiced" at Shenandoah is an "infringement of constitutional principles" because it was not equal, although separate.

Superintendent Lassiter defended the evolving Lewis Mountain development, and after a review of facilities at Shenandoah requested by Director Cammerer, with input by Senator Harry Byrd, it was decided by the Secretary that state laws and local segregationist policies would be “generally” followed, but that one large picnic area in Shenandoah would be integrated. Pinnacles Picnic Ground was selected for the Park's initial integration effort in 1939.

Portions of the Lewis Mountain facilities opened in the summer season of 1939 and the first cabins and lodge were in service in the summer of 1940. However, Virginia Sky-Line Company remained unsupportive of the development and wrote Superintendent Lassiter that the Lewis Mountain operation would probably operate at a loss causing the other white facilities to "bear an unreasonable [financial] burden."

Arno Cammerer, now Director of the National Park Service, and his staff supported the Virginia Sky-Line Company position, stating:

I myself have felt right along that there was not sufficient demand for negroes for this particular type of accommodations to make it pay, but I understand that the Secretary [of the Interior] has insisted on the installation and that this is why they are progressing. Next year if it does not pay, we can take up the question of closing it or making it available for white occupancy. I think…[staff] had better advertise this, sending copies to Howard University.

This widely circulated memorandum may well have been the final nail in Cammerer's coffin. On February 11, 1939, National Park Service Associate Director Arthur E. Demary drafted this memorandum (292kb pdf) to Cammerer concerning segregated facilities in Shenandoah, emphasizing that the Secretary of the Interior insisted on having facilities for blacks equal to those for whites. In June, Secretary Ickes quietly offered the Directorship to Newton Drury, who accepted, shortly before Cammerer officially resigned as National Park Service Director and became a Regional Director at Richmond.

Superintendent Lassiter suffered a heart attack on December 26, 1939 and was not back at work until late spring of 1940. He possibly did not comprehend the significance of the directive from Washington that was received in the Park during his absence, stating that "no mention will be made of segregation on the map or in the park literature." In August he unguardedly wrote to the Director:

“I think the best policy to pursue is definite segregation, either by separate areas or by setting aside a portion of each area for Negroes. Of course, neither of these suggestions will meet with the approval of that group of Negroes...who...must have their millennium [sic] at once…”

In September 1940, Lassiter was called to Washington to explain why Park Rangers continued to give out maps and brochures identifying Lewis Mountain as the campground and lodge "for colored visitors." Soon thereafter, Lassiter received orders to transfer to the Superintendency at Great Smoky Mountains Park, a transfer that was indefinitely postponed due to political pressure. But within a year Lassiter had been exiled to Santa Fe, New Mexico, as Regional Engineer with a cut in grade and a 10 percent loss in salary.

During World War II, gasoline was rationed, visitation plummeted, and park concession facilities closed. Virginia Sky-Line Company did not begin to reopen facilities until September 1945. In December, a general bulletin to all National Park Service concessionaires was issued by Washington calling attention to Federal Register, December 8, 1945, page 14866, mandating full desegregation of all facilities in national parks. Virginia Sky-Line Company's manager protested to Superintendent Freeland:

In March 1939, a few days after the present officers acquired controlling stock [of Virginia Sky-Line Co.]…a conference was held…at which there was present the majority of the [NPS] Director's Staff…In return for the expenditure of funds necessary to carry out these plans [for facilities development], this company was assured that the facilities at Dickey Ridge, Elkwallow, Skyland and Big Meadows would be reserved for the exclusive use of White people…and as evidence of the Park Service's intentions…the Lewis Mountain development has always carried the designation, ‘for the exclusive use of negroes.’…Instead of improving racial relations, [it] would be a distinct dis-service to the negroes desiring to visit the park.

Washington accepted the reality of Virginia Sky-Line Company's threat to give up its contract with the National Park Service if the proposed regulation was imposed, and an internal National Park Service memorandum noted that

General Manager [of Virginia Sky-Line]…has been, or soon will be, given assurance, through Senator Byrd, that the Company may continue its operations this summer without any change in its plans with respect to taking care of Negro visitors.

Frazier, the general manager of Virginia Sky-Line Company, resigned the following year and in October 1947, Lewis Mountain and the main dining room at Panorama were integrated by the new manager. Gradually, the concessionaire and the Superintendent worked to assure fully integrated facilities, a task accomplished in the summer of 1950, more than a decade before similar results elsewhere in the Commonwealth.