Part of a series of articles titled Creative Teaching with Historic Places: Selections from CRM Vol 23 no 8 (2000).

Article

Seeing is Believing: Teaching with Historic Places Field Studies

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GA_Savannah_Owens-Thomas_House08.jpg

Published by the National Park Service, Cultural Resources

by Marilyn Harper

Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) has demonstrated that historic places help students learn even when visits are impossible. Nevertheless, visiting historic places in person gives a special sense of being “in history.” Eleven of TwHP’s workshops have used walking tours that investigate local historic places to demonstrate how field studies can enrich learning of both content and thinking skills.[1] These studies also have provided exciting confirmation that careful observers can learn much from historic places simply by looking. While our methodology is still evolving, we hope that the seven-step process we follow will help both historic preservationists and teachers create field studies using historic places in their own communities. Each step is outlined below, with an illustration of how it worked for a recent workshop in Savannah, Georgia.

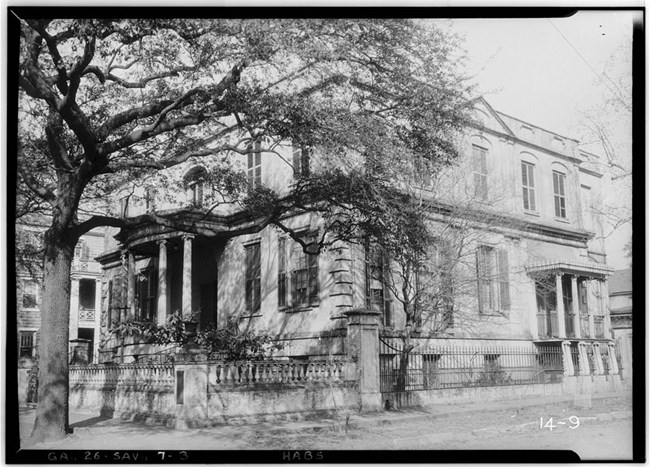

1. Picking the Place. The first step is deciding where the field study will go. Ideally the place will be well-documented, visually interesting, and able to tell an important story. Because the TwHP program was created, in part, to demonstrate the richness of the National Register archives, our field studies use only listed properties. We picked the 1819 Owen-Thomas House and the city’s distinctive Colonial plan for the Savannah study.[2]

2. Doing the Research. Using National Register documentation simplifies this critical phase of planning. Learning about some places may involve doing further research or finding a knowledgeable expert. In Savannah, Register documentation was supplemented by scholarly work on the city plan and by the knowledge of the Owens-Thomas House curator. Research also uncovers documents that help participants test tentative conclusions during the follow-up discussion (see Step 7). In Savannah, these materials included historic maps and views, travelers’ descriptions, biographical information on the original owner, floor plans, and photographs.

3. Select a Focus. Most historic places have many stories to tell. The best way to determine which story should be the focus for the field study is to identify ties between the place and the content and skills required in local curricula. In Savannah, the focus was on the relationship between the antebellum city and the institution of slavery. Objectives included comparing (skill) early-19th-century Savannah with its appearance in 1734 (content), evaluating (skill) the effect of the introduction of slavery on what was planned as an egalitarian society (content), and analyzing (skill) the Owens-Thomas House for evidence of the role of slavery (content).

4. Planning the Tour. The field study must provide the physical evidence participants need to attain the objectives. The planning must be done on site. In Savannah, we mapped the route from the workshop orientation to the Owens-Thomas House to show how the house fit into the city’s well-defined plan.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.ga0091.photos/?sp=3

6. Introducing the Field Study. In addition to establishing work groups, selecting spokespeople, handing out maps and worksheets, etc., introductions sometimes include background information. Providing a historical context before the field study establishes a conceptual framework for subsequent observations. In Savannah, we reduced the amount of background to a minimum, which also has advantages. Observation is not directed by expectations – people look around them as children do, without editing what they see. Also, historical information that answers questions raised by observation is likely to be remembered. Finally, when participants find answers for themselves, they experience some of the excitement of real historical inquiry.

7. Follow-up Discussion. This is the most exciting part of our field studies, but also the one where much work still needs to be done. Groups invariably come back excited at what they have seen – detectives who have unearthed important evidence, even though they do not yet know where that evidence leads. It is a challenge to preserve that excitement while still guiding the discussion to meaningful conclusions, to validate observations and let generalizations grow naturally while ensuring that these generalizations fit curriculum needs. It is also difficult to both demonstrate content – what a specific places teaches about history – and also model a process that progresses from looking at places to understanding them.

Effective discussions advance from specific observations to higher-level generalizations. Teaching strategies developed for classroom teachers provide useful models. [4] Our recent discussions have stressed observation – “what did you see?” In Savannah, participants noticed first that the houses facing the squares were larger than those facing the streets, that the Owens-Thomas House featured sophisticated architectural details and advanced technology, and that the slave quarters/carriage house differed greatly from the main house. Putting these observations together, they hypothesized that Savannah had a skilled labor force; that the builder of the house valued social life, prestige, and status; that trade and European connections were important; and that the city was divided into distinct classes. Historic maps, visual materials, and descriptions helped confirm these conclusions.

In addition to developing the above 7-step planning process, which we think will work in a variety of situations, we also have learned two general principles. First, timing is critical. It is difficult to complete an effective field study in less than one day. Secondly, teamwork can both improve the quality of field studies and simplify the process of creating and conducting them. Historians and people knowledgeable about places can locate the places for field studies and find appropriate source materials. Teachers can see where the places and the skills involved in learning from them fit into the curriculum. Teachers also know the teaching strategies and questioning techniques that make for good discussions. We believe these groups can work together to create field studies that are exciting learning experiences for participants of all ages.

Notes

[1] We prefer the term “field study” to the more common “field trip” because it emphasizes learning over entertainment.

[2] All types of places lend themselves to field studies. Other places TwHP has selected for these workshops include Union Station in St. Louis; downtown Fort Worth, Texas; Chicago’s Grant Park; Santa Fe (NM) Plaza; and Antietam Battlefield.

[3] “Walk Around the Block: Old East Dallas Architivities Packet.” (Prairie Village, KS: Center for Understanding the Built Environment, 1992), 32.

[4] See Charles S. White and Kathleen A. Hunter, Teaching with Historic Places: A Curriculum Framework for Professional Training and Development of Teachers, Preservationists, and Museum and Site Interpreters (Washington, DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1995), 46-50.

At the time of writing, Marilyn Harper was a historian with the National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service.

Last updated: April 27, 2023