Last updated: April 9, 2020

Article

SEAC Zooarcheologists Combine Sciences to Study the Past

In as much as archeology stands alone as a professional and intellectual pursuit, it is privileged to also be a sort of axis discipline that relates data from other fields of study to the human past. Like any strong field of inquiry, archeology draws on multiple lines of evidence derived from the results of its own diverse suite of research methods and those of other disciplines.

In some cases, these other disciplines are tied directly to a subfield of archeology. Zooarcheology is a particular case in point. Zooarcheology combines anthropology and archeology with zoology, biology, ecology, and climatology to study the past relationships between people and animals.

SEAC Zooarcheologists Alex Parsons and Brian Worthington are practiced experts in highlighting not only how past peoples interacted with animals but also how different animals can teach us things about the nature of the past environments in which people lived.

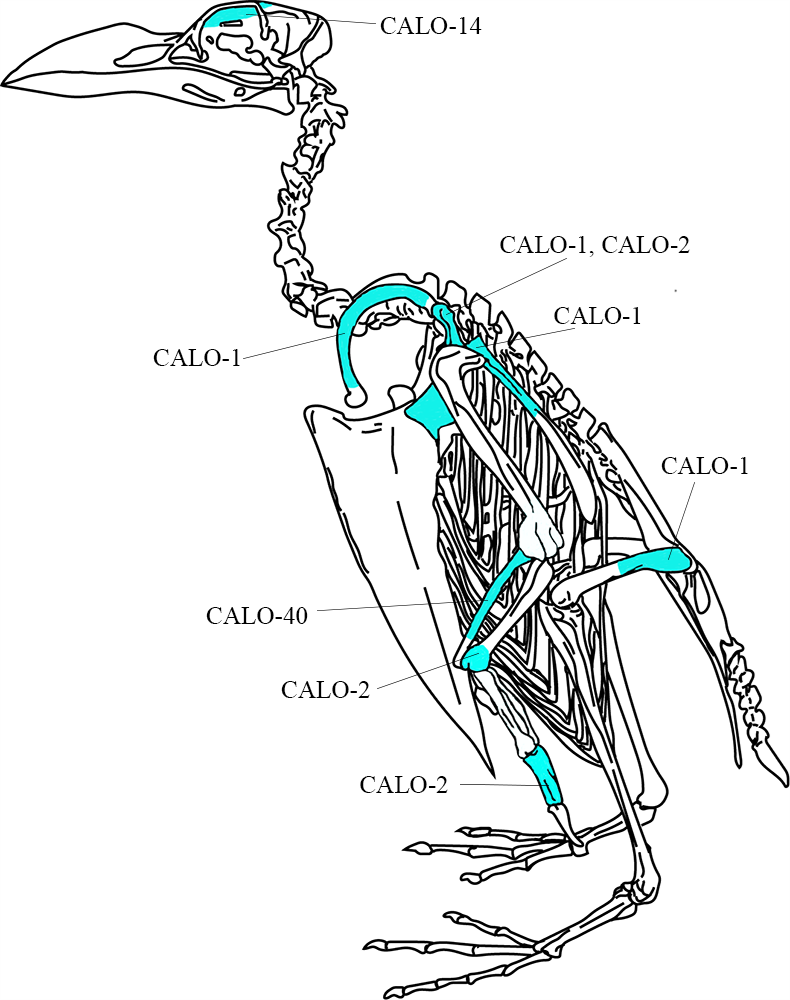

Brian works in the Regionwide Archeological Survey Program division at SEAC. Recently, he has been analyzing and describing the entire faunal collection from SEAC's investigations at Cape Lookout National Seashore CALO) in North Carolina. Some of the research questions guiding his studies include determining the different time periods during which people have lived on the Outer Banks, comparing historic and prehistoric adaptions to island life, determining the different environments prehistoric and historic populations exploited for food and raw materials, and exploring the different methods and technologies of hunting and gathering.

(NPS Photo by Brian Worthington)

Brian says it was particularly exciting to identify specimens of the extinct great auk (Pinguinus impennis) in historic and prehistoric contexts at Cape Lookout, and other very rare, related bird species like the little auk or dovekie (Alle alle) and razorbill (Alca torda).

The kinds of animals present in the collection offers clues about the possible over-exploitation of certain species or environments. For example, if more large grouper specimens show up early on but smaller grouper is more common later, this may suggests that people were forced to settle for smaller grouper after they over-fished the large grouper. Similarly, people may be forced to venture farther afield for food when the abundance of inshore species decreases from over-exploitation.

Comparative collections are one of the most important tools in zooarcheology. These collections are made up of the shells and complete skeletons of animals about which much is known; for example, when, where, and how the animals lived and died. By comparing these modern specimens with archeological specimens, zooarcheologists can go beyond simply identifying what species are present to answering questions about whether a particular specimen is from a male or female, what kind of environment the animal lived in, how old it was when it died, and much more.

Dr. Alex Parsons is a zooarcheologist in the NAGPRA and Applied Science division at SEAC. She has recently been spending much of her time developing a comparative collection of a kind of clam called a quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria) from the brackish sound on the east side of Cape Lookout. Once complete, the comparative collection will be used to study the shells which make up the middens (piles of prehistoric garbage) at CALO.

(NPS Photo)

Follow this link to a short video by Dr. Parsons explaining how to tell time with shells!

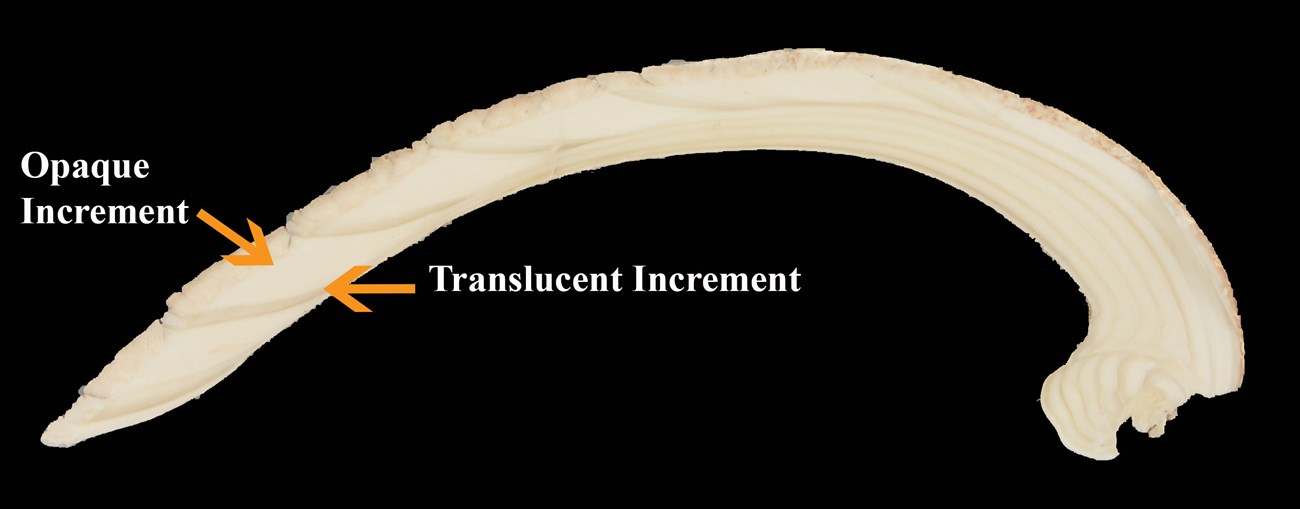

One of Alex's research objectives is to determine whether prehistoric Native Americans at CALO were creating the shell middens year round or during specific seasons. Throughout their lives, clams grow rings much like trees. To determine the season in which a group of clams died, a zooarcheologist must know what the rings that form during different seasons look like. Each year, a clam grows a set of two rings, one translucent and one opaque. The translucent ring is a response to seasonal stress. In warmer, southern climates, this stress is induced by hot summer temperatures. In the cooler, northern climates, cold winter temperatures cause the clams to grow their translucent ring. CALO is located near threshold between these different seasonal growth patterns so determining what season a group of clams died becomes extra tricky.

(NPS Photo)

That's why a larger than usual comparative (or "baseline") collection from the local area is necessary. To build the CALO quahog comparative collection, 40-50 clams were collected each month for two years. That's between 960 to 1200 clams! Once these are cut and measured, Alex will move on to cutting and measuring the hundreds of archeological clams collected from the CALO middens.

Archeology has the potential to fill in gaps in written histories and to tell the story of peoples whose histories have been lost or have gone unrecorded. Zooarcheologists, by studying archeological remains through the lens of anthropology in conjunction with zoology, biology, ecology, and climatology, flesh out the contexts of past human life and how people and other animals experienced the world in which they lived.

You can listen to Alex Parsons' and Brian Worthington's 15 Questions With an Archeologist