Last updated: August 2, 2023

Article

Savannah, Georgia: The Lasting Legacy of Colonial City Planning (Teaching with Historic Places)

Few places in America possess the breadth of natural and designed scenic beauty, the magical and eerie charm, and the immediate presence of the past as the historic district of the city of Savannah, Georgia. Strolling through the old city's rigid, grid pattern streets, down its linear brick walkways, past over 1,100 residential and public buildings of unparalleled architectural richness and diversity, visitors and residents come to appreciate the original plan which has existed intact since Savannah's founding in 1733. Twenty-four tree-shaded, park-like open spaces called "squares" are the essence of the city. One of the few surviving colonial city plans in the United States, Savannah is a testament to the ingenuity of Georgia's founders.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file for "Savannah Historic District" (with photographs). It was produced in collaboration with the National Park Service Historic Landscape Initiative. Judson Kratzer, Senior Archeologist at the Cultural Resource Consulting Group in Highland Park, New Jersey, wrote Savannah, Georgia: The Lasting Legacy of Colonial City Planning. Jean West, education consultant, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff edited the lesson. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson plan can be used to teach colonial history, the antebellum era and the cotton economy, and the rise of cities in the United States.

Time period: 18th to 20th centuries

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Savannah, Georgia: The Lasting Legacy of Colonial City Planning

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 2: Colonization and Settlement (1585-1763)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands how diverse immigrants affected the formation of European colonies.

-

Standard 1B- The student understands the European struggle for control of North America.

-

Standard 2A- The student understands the roots of representative government and how political rights were defined.

-

Standard 3A- The student understands colonial economic life and labor systems in the Americas.

-

Standard 3B- The student understands economic life and the development of labor systems in the English colonies.Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 2D- The student understands the rapid growth of "the peculiar institution" after 1800 and the varied experiences of African Americans under slavery.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Savannah, Georgia: The Lasting Legacy of Colonial City Planning

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard A - The student compares similarities and differences in the ways groups, societies, and cultures meet human needs and concerns.

- Standard C - The student explains and gives examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

- Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

- Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard B - The student analyzes groups and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

- Standard D - The student identifies and analyzes examples of tensions between expressions of individuality and group or institutional efforts to promote social conformity.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict and establish order and security.

- Standard I - The student uses economic concepts to help explain historical and current developments and issues in local, national, or global contexts.

Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationships to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants and security.

- Standard C - The student describes examples in which values, beliefs, and attitudes have been influenced by new scientific and technological knowledge, such as the invention of the printing press, conceptions of the universe, applications of atomic energy, and genetic discoveries.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard C - The student describes and analyzes the effects of changing technologies on the global community.

-

Standard E - The student describes and explains the relationships and tensions between national sovereignty and global interests in such matters as territory, natural resources, trade, use of technology, and welfare of people.

Objectives for students

1) To explain why the Trustees established the colony of Georgia and the significance of Gen. James Oglethorpe's role in its founding.

2) To distinguish the egalitarian design elements of Oglethorpe's original city plan and evaluate how commercial success affected them in the 19th century.

3) To demonstrate understanding of a utopian/egalitarian design or concept and to formulate reasons why such idealized concepts may fail to fit in with political, economic, social, and cultural reality in daily life.

4) To analyze, compare, and contrast their own urban/town area with the design elements and features apparent in Savannah's city plan.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps of the Atlantic Southeast coastline;

2) three readings about Savannah's founding and development;

3) four drawings of historic Savannah;

4) one painting of 19th-century Savannah.

Visiting the site

From I-95, exit onto I-16 east and proceed 10 miles to downtown Savannah. Information is available at the Savannah Visitors Center, in the restored Central Railroad of Georgia station at 301 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard, at the end of I-16. The visitors center is open Monday through Friday 8:30 a.m.-5:00 p.m. and weekends 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What patterns do you see in the way this town is being built?

Setting the Stage

Today's state of Georgia was the last American colony established by the English crown, and the city of Savannah was its first town. The seeds for both were planted in 1732, when a group of Englishmen came together and formed The Trustees for Establishing the Colony of Georgia in America. Their leader was General James Oglethorpe, a member of the House of Commons since 1722. While in the House, one of Oglethorpe's friends was jailed for debt and died of smallpox. Oglethorpe asked Parliament to appoint a committee which investigated the suffering of debtors in London jails. They formed the committee in 1728, naming Oglethorpe as chairman. This experience persuaded Oglethorpe and his fellow committee members that an American colony should be established for relief of the needy and those of modest means.

In 1733, Oglethorpe and his original band of 114 settlers arrived on the southeast Atlantic coast. He selected a site on a high bluff overlooking the Savannah River for the site of his new town. Oglethorpe directed the design and construction of the settlement, basing it on English city planning principles. The grid pattern of streets, wards, and "trustee lots" was interspersed regularly with park-like squares. As the city grew, the plan was repeated. Although architectural styles and building materials changed over the 18th and 19th centuries, the Oglethorpe plan continued to be the city's framework.

Locating the Site

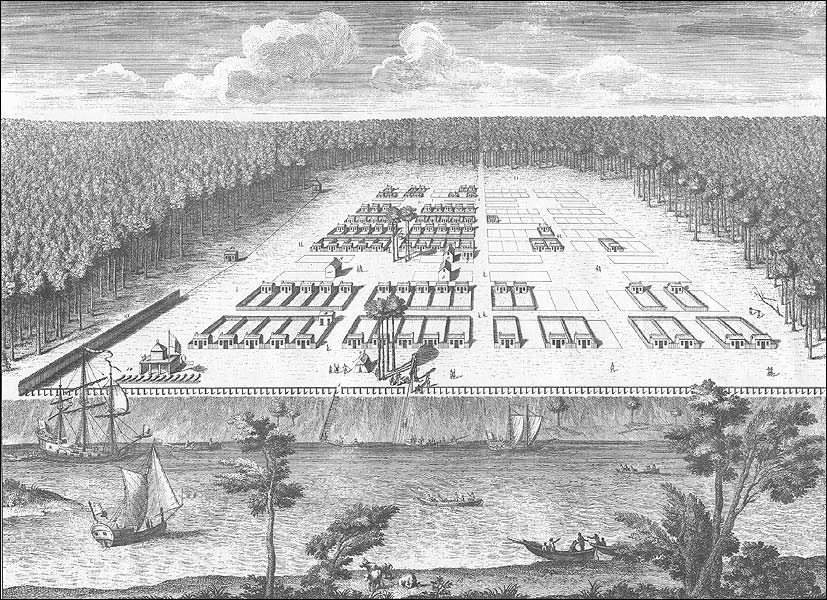

Map 1: British and Spanish claims in the Southeast.

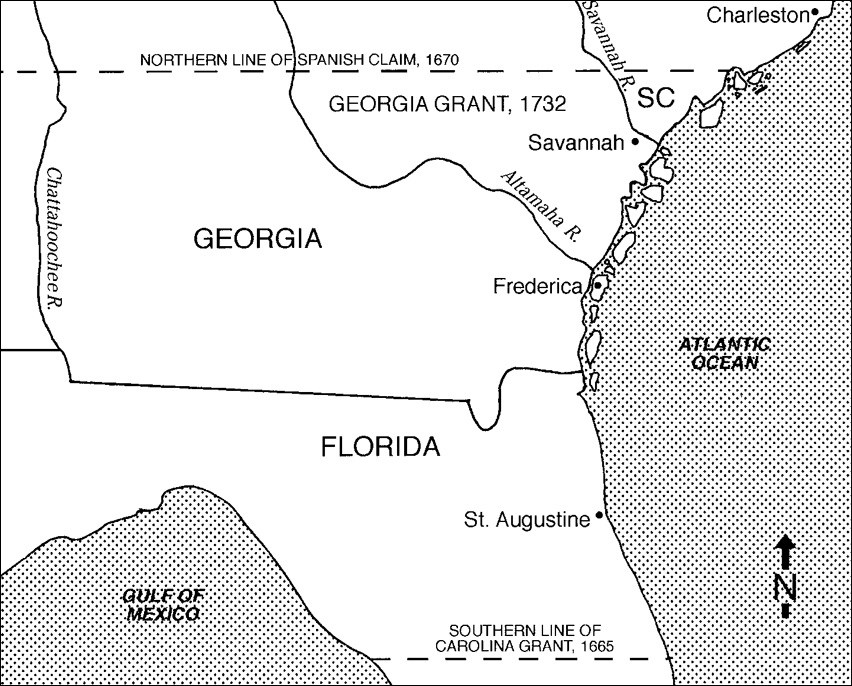

Map 2: Portion of the southeast Atlantic coastline.

(Fort Frederica Association)

The land claims of both England and Spain overlapped in what is now southern Georgia and northern Florida. One of Oglethorpe's missions was to establish a permanent settlement which would serve as a buffer between the Spanish fort at St. Augustine and the English city of Charleston, South Carolina.

Questions for Maps 1 & 2

1. Identify the three states represented in Map 1.

2. Why do you think it was possible for both Spain and England to claim the same land?

3. Locate Charleston and St. Augustine on Map 2. Use the scale to measure the distance between these two settlements. Why would it have been important for England to establish a colony between St. Augustine and Charleston?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Establishing Savannah

In 1732, most of what we know today as southern Georgia and northern Florida was considered a "no man's land" because this land area was claimed by both England and Spain and was home to many tribes of Indians. When the Trustees of Georgia applied in 1732 for a charter from King George II to settle this contested area, the monarch readily granted it to them. He believed the settlement would provide an important buffer between the Spanish stronghold of St. Augustine and the main English town of the Carolinas, Charleston.

With the blessings of the Trustees, Oglethorpe led a sea voyage from England to America aboard the ship Anne which landed in Charleston, South Carolina, in early February 1733. That voyage included 114 men, women, and children who hoped for a better opportunity to carve out an agricultural livelihood in Georgia. Although Oglethorpe had hoped to draw his colonists from those released from debtor's prison or struggling with dire poverty, the descriptions of Georgia as a "promised land" attracted a very different group. They included laborers, adventurers, and merchants, a group drawn from the middle class rather than former debtors.

Oglethorpe explored further down the coast for a viable site, eventually deciding to establish his new settlement on a high bluff on the western bank of the Savannah River, approximately 10 miles from the Atlantic Ocean. Pleased with the geographical advantages of the site, Oglethorpe set about befriending the local Indian population. Oglethorpe and Tomachichi, the Yamacraw Indian chief (or Mico), became friends and a mutual respect developed between these two men. This friendship led to stable relations between Savannah's settlers and Tomachichi's Yamacraw tribe. Several years later, Oglethorpe took Mico Tomachichi and several of his tribesmen to England to visit London and the King and Queen. With security and friendship firmly established between settlers and local Indians, Oglthorpe felt comfortable sending this account to the Trustees:

I chose this Situation for the Town upon an high Ground, forty feet perpindicular above High Water Mark; The Soil dry and Sandy, the Water of the River Fresh, Springs comming out from the Sides of the Hills. I pitched upon this Place not only from the Pleasantness of the Situation, but because from the above mentioned and other Signs, I thought it healthy; For it is sheltered from the Western and southern Winds (the worst in this Country) by vast Woods of Pine Trees, many of which are an hundred, and few under seventy feet high. The last and fullest consideration of the Healthfulness of the place was that an Indian nation, who knew the Nature of this Country, chose it for their Habitation.¹

It was the Trustees' intention to develop an egalitarian settlement, that is a town divided in a way where all residents had equal amounts of land and, consequently, opportunity. They expected the settlers to be industrious, become self-sufficient food producers, and eventually to produce surplus goods that could be sent back to England. However, they also realized that developing a town in a land filled with danger needed defensive protection from possible attacks either by Indians or the Spanish.

The Trustees placed limits on the settlers to maintain equality and order, defensive readiness, and to prevent bad behavior:

1) Settlers were each allocated one town lot, a five acre garden plot for food production and a 45-acre farm outside the town limits. The equal land allotment promoted equality and limited land speculation. It was hoped it would inspire an industrious attitude among the settlers.

2) No slavery or negroes were permitted in the colony to ensure that the settlers led industrious lives and worked their own land.

3) Settlers had to trade fairly and equally with their Indian neighbors, to prevent Indian opposition to Georgia's growth and possible devastating attacks.

4) Rums, brandies, or distilled spirits were strictly prohibited in the colony, to ensure good behavior and industrious lives.

5) No paid lawyers were allowed to practice in the colony. All persons accused of a crime pled their own cases before the grand and petty juries; the Trustees believed this would maintain equality in civil and criminal matters.

The Trustees hoped these rules would insure the survival of the fledgling colony of Georgia by preventing from the outset the ills which had doomed other colonizers' efforts.

Questions for Reading 1

1. James Oglethorpe is believed to have given the city of Savannah its name based on the geographic features he found near the bluff where he landed. Look up the definition for savanna in a dictionary? Are there such natural landscapes in your area?

2. What are two reasons why the English wanted to develop the colony of Savannah?

3. Define and then discuss the similarities and differences between the terms "egalitarian" and "utopian." Decide which term best fits the type of development James Oglethorpe had in mind for Savannah. Explain.

4. Examine your textbook or a general U.S. history reference book about early relationships between English colonists and the Indians on whose land they were settling. Which of these relationships were pleasant and friendly? Which were not. If not, why? On the whole, was Oglethorpe's relationship with the Yamacraw typical of English-Indian relationships?

5. Why did the Trustees place restrictions on the settlers? What were they? Do you think the restrictions were reasonable or unreasonable? Explain.

Reading 1 was compiled from James E. Oglethorpe's correspondence in the Earl of Egmont Papers at the University of Georgia; Preston Russell and Barbara Hines, Savannah: A History of Her People Since 1733 (Savannah: Frederic C. Beil, 1993); and Phinizy Spalding and Edwin Jackson, James Edward Oglethorpe: A New Look at Georgia's Founder (Athens, Ga.: The University of Georgia Press, 1998).

¹James Oglethorpe to the Trustees, February 10 and 20, 1733, in John Percival, the Earl of Egmont Papers, Phillips collection, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries, 14200: 34-35.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The City Plan and How It Was Built.

Having found an ideal place to settle and having established good relations with the local Indian population, Oglethorpe set upon designing the city he would call Savannah. Taking into account the Trustees desire for a city promoting equality as well as protection, Oglethorpe came up with a simple, yet sophisticated, design that reflected both egalitarian principles and classical standards of fortress construction.

His basic module of design was a square-shaped unit called a "Ward." At the center of each ward was a large, open space called a "Square." The four corners of each ward contained a "Tything." A tything consisted of ten house lots each. These ten house lots were reserved for the private homes of the settlers. Each house lot measured the same, 60 feet in width and 90 feet in depth. The relationship between the position of the house lots and square insured that the residents of each ward had a natural meeting location. The squares drew both local inhabitants and visitors to the city and gave all a place to mingle. On the east and west flank of the square were positioned four larger lots called the "Trustees Lots." They were reserved for public structures, such as churches, banks, or government buildings. Little did Oglethorpe know that this design lavished more open space on Savannah than probably any town in American history.

Peter Gordon, who traveled with the original settlers to Georgia along with Oglethorpe on the Anne, described the effort required and the length of time needed to construct the first four wards of James Oglethorpe's design.

We arrived the 1st of February at Yamacraw Bluff, the place Mr. Oglethorpe had pitched upon for our settlement. As soon as we landed, we set about getting our tents fixed and our goods brought ashore and carried up the bluff, which is forty feet perpendicular in height. This, by reason of the loose sand and great height, would have been extremely troublesome had not Captain Scott and his party built stairs for us.About an hour after our landing, the Indians came with their king, queen, and Mr. Musgrove, the Indian trader and interpreter, to pay their compliments to Mr. Oglethorpe and to welcome us to Yamacraw. The king, queen and chiefs and other Indians advanced and before them walked one of their generals with his head adorned with white feathers with rattles in his hands, to which he danced, singing and, throwing his body into a thousand different and antic postures....

Friday the 2nd, we finished our tents and got some of our stores on shore. The 3rd we got the periaquas unloaded and all the goods brought up to the bluff. Sunday the 4th, we had divine service performed in Mr. Oglethorpe's tent.

Wednesday the 7th, we began to dig trenches for fixing palisades 'round the place of our intended settlement as a fence in case we should be attacked by the Indians, while others of us were employed in clearing the lines and cutting trees to the proper length for the palisades.

Thursday the 8th, each family had given out of the stores an iron pot, frying pan, and three wooden bowls, a bible, a common prayer book. this day we were taken off from the palisades and set about sawing and splitting boards eight feet long.

Friday our arms were delivered to us from the store, viz., a musket and bayonet, cartridge, box, and belt, to each person able to carry arms. Sunday, we were drawn up under our arms for the first time, being divided into four tythings, each tything consisting of ten men. I mounted the first guard at 8 o'clock at night, received orders from Mr. Oglethorpe to fix two sentinels at the extreme parts of the town to be relieved every two hours.

March, 1st, the first house in the square was framed and raised, Mr. Oglethorpe driving the first pin. Before this we had proceeded in a very unsettled manner, having been employed in several different things such as cutting down trees and cross-cutting them into proper lengths for clapboards and afterwards splitting them in order to build clapboard houses. That not answering the expectations we were now divided into different gangs and each gang had their proper labor assigned to them under the direction of one person. so we proceeded in our labor much more regular than before, there being four sets of carpenters who had each of them a quarter of the first ward allotted to them to build, a set of shingle-makers with proper people to cross-cut and split and a sufficient number of Negro sawyers hired from Carolina to be assisting us.

April, 6th, Mr. Oglethorpe ordered that Dr. Cox, the first that died, should be buried in a military manner. All our tythings were ordered to march under arms to the grave with the corpse. We gave the general discharges of our small arms, guns were fired from the guard house and the bell constantly tolling. This manner of burying was observed till the people began to die so fast, three or four in one day, that the frequent firing of the cannon and our small arms struck such terror in our sick people (who, knowing the cause, concluded they should be the next) that Mr. Oglethorpe ordered it should be discontinued.¹

In 1736, James Oglethorpe's attention was redirected to St. Simons Island, about 80 miles south of Savannah. He had found there a much stronger defensive position against possible Spanish attack from St. Augustine. On the island's western edge, he designed and built Fort Frederica. In July 1742, the anticipated Spanish attack was launched on Georgia. Spanish troops landing on St. Simons Island met Oglethorpe's defenders near Fort Frederica. The resulting Battle of Bloody Marsh, won by the British, led to the elimination of the Spanish threat from Florida. Having secured the British land claim down to the southern Georgia border, James Oglethorpe soon returned to England, satisfied that he had succeeded in creating two towns (Savannah and Augusta) based on egalitarian principles in a safe place where future immigrants could also seek a better life.

Questions for Reading 2

1. Savannah is divided into a series of design units, or modules. What term did Oglethorpe use for his basic module (unit) of planning? List the divisions within the module.

2. What did the colonists live in before they built their houses?

3. What is a palisade and why would the colonists need to build one? Can you use the reading context to figure out what a periaqua is?

4. What supplies and arms were issued to each colonial family?

5. Describe the materials the first settlers used to build their houses and fences. How did they acquire this material?

6. How did the Spanish and British colonists resolve their dispute over the boundaries of Florida?

Reading 2 was compiled from Mills Lane, Savannah Revisited: History and Architecture, 4th ed. (Savannah: Beehive Press, 1994); Preston Russell and Barbara Hines, Savannah: A History of Her People Since 1733 (Savannah: Frederic C. Beil, 1993); and Phinizy Spalding and Edwin Jackson, James Edward Oglethorpe: A New Look at Georgia's Founder (Athens, Ga.: The University of Georgia Press, 1998).

¹From the diary of Peter Gordon in the collection of the University of Georgia.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Good Intentions Don't Always Last

Without Oglethorpe's strong leadership, the Trustees' original restrictions began to erode as Georgians sought more personal freedom to engage in commerce. A number of individuals had invested in larger plats of land where they hoped to increase their production of high-demand crops such as cotton, rice, and indigo. Because of the greater quantity of land to be farmed and the labor-intensive character of these lucrative products, owners and their families could not do the work themselves, and there were not enough free laborers to fill the need. Thus, the large landholders wanted to use slaves in their fields and clamored for slavery to be permitted in the colony. The Trustees resisted lifting the ban but finally gave in to the colonists' demands in 1750. Eventually all the limitations imposed upon the first colonists were lifted by the Georgia government and, by the 1790s, slavery had become an integral, if abhorrent, element in the colonial economy.

The 1793 invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney at Mulberry Grove Plantation, about 10 miles north of Savannah, cemented Georgia's dependence on slave labor. Upland cotton, which could grow in mainland Georgia, was full of sticky seeds. Because it took a person a full day to pick a pound of cotton clean, the crop was not profitable. Whitney's gin (engine) combed through the cotton, removing the seeds. Fifty pounds of cotton could be cleaned by a hand-cranked gin by a single person in a day. With the sudden profitability of upland cotton, planters sought more land, displacing the Indian tribes with whom Oglethorpe had established such good relations, and planted more cotton, fueling demands for more and more slaves. Cotton was "King."

Eli Whitney's cotton gin also turned Savannah into one of the world's largest exporters of cotton, especially to Great Britain's recently industrialized textile manufacturers. Steam-powered spinning jennys and mechanical looms transformed Georgia's raw cotton into cloth sold around the world. Plantation owners, merchants, and cotton brokers dominated Savannah's economic, social, and cultural life. They exhibited their wealth by constructing homes in the latest styles. Although the plain, egalitarian wooden homes constructed during Oglethorpe's tenure were gradually replaced by brick and stucco mansions and the population expanded, the original city plan was never altered. As the city grew, new ward modules were laid out, replicating the first four in size and shape, and people built new homes within the same house lot sizes as the original settlers, as this 1833 observer recorded:

What constitutes its beauty is the manner in which the city is laid out. There is one immensely broad avenue, about half way across the city, called South Broad Street, and extending the full length of it from east to west. This is magnificently shaded by rows of China trees...full of small odorous blossoms in the spring of the year. Then in laying out the city every other square has been left as an open one, enclosed with a railing, laid out with walks and planted with shade trees and rustic seats arranged in them all about. These manifold grassy parks, or lungs of the city as I heard them called, are very picturesque and inviting, and highly suggestive of health and comfort.At this time in the year Savannah is swarming with wagons. As they come into the city with their heavy loads, sometimes as many as eight bales of cotton on a wagon, each driver appears to be trying to see who can make the most noise with his long whip. It is these whips, they say, which have given to the country people the sobriquet of 'cracker.' These cracker women wear long bonnets, projecting far over the face, made of coarse homespun.

The market here is managed mostly by Negroes--at least they do all the selling. Negro women preside over the stalls of vegetables, chickens and eggs. The tiers of carts around the market are unique in their appearance. Most of them are of domestic manufacture, all but the wheels. The bodies of them are made of boards rived out by hand from forest trees and, in the absence of nails, fastened together by pegs. Long withes of hickory or some other pliant wood forms an arch over the top.

Should one of these queerly dressed and bonneted women appear on Broadway I think there would be a mob around her in less than two minutes. But these fruit and vegetable venders are such a familiar sight here that they attract no attention.²

Ironically, Savannah had clung to the egalitarian framework of its city plan even as it had embraced the institution of slavery and fragmented into economic classes.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Why did the colonists want to introduce slavery into Georgia?

2. How did Eli Whitney's cotton gin change Georgia's economy? How did the cotton gin contribute to the growth of slavery in Georgia?

3. Why did the English buy cotton from their former colonies in America?

4. Who grew rich from the thriving cotton economy? Who suffered from the thriving cotton economy?

5. In what ways did the city of Savannah change because of the profits made from cotton? In what ways did it remain the same as Oglethorpe originally envisioned?

Reading 3 was compiled from Mills Lane, Savannah Revisited: A Pictorial History, 1st ed. (Savannah: University of Georgia Press, 1969) and Preston Russell and Barbara Hines, Savannah: A History of Her People Since 1733 (Savannah: Frederic C. Beil, 1993).

¹Sara Hathaway, Old Homestead, April, 1891; quoted in Mills Lane, Savannah Revisited: History and Architecture, 4th ed. (Savannah: Beehive Press, 1994), 46-47.

²Mills Lane, Savannah Revisited: A Pictorial History, 1st ed. (University of Georgia Press: Athens, 1969), 88.

Visual Evidence

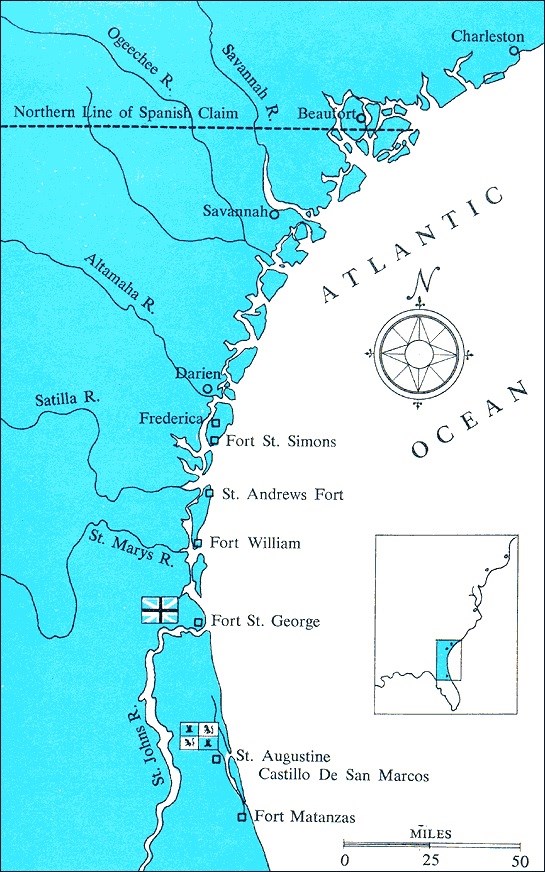

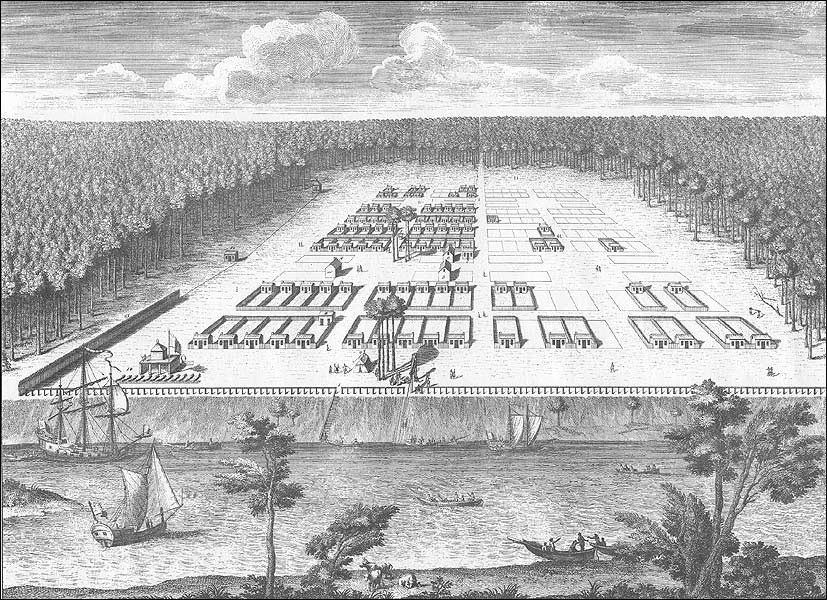

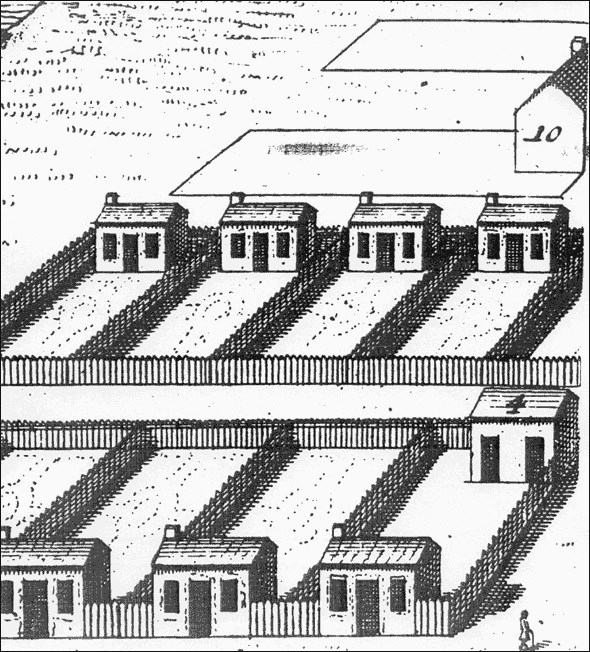

Drawing 1: View of Savannah, 1734.

Drawing 2: Enlarged detail from View of Savannah, 1734.

(Courtesy of the Georgia Historical Society)

This view of Savannah was prepared by London engraver P. Fourdrinier in 1734, based on a sketch generally attributed to Georgia colonist Peter Gordon. The picture details the progress made in building the town of Savannah and displays many of the features that Peter Gordon wrote about (see Reading 2).

Questions for Drawings 1 & 2

1. Four wards are represented in Drawing 1, although some have not yet been fully completed. Since you are looking south, which ward is most nearly complete, with all the lots filled with buildings?

2. Drawing 2 is an enlarged detail of the View of Savannah, Drawing 1. Using clues in the enlargement, identify from which portion of the original drawing the enlargement was taken. Does looking at a detail help you to see new things or confuse you? Explain.

3. Compare Drawing 1 with the account given by Peter Gordon in Reading 2. List the landscape and built or constructed features in Drawing 1 that were also described by Peter Gordon in his account.

4. What details does the picture provide that the written account does not? What details does the written account supply that the picture does not? Is Drawing 1 an accurate representation of the account given by Peter Gordon? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

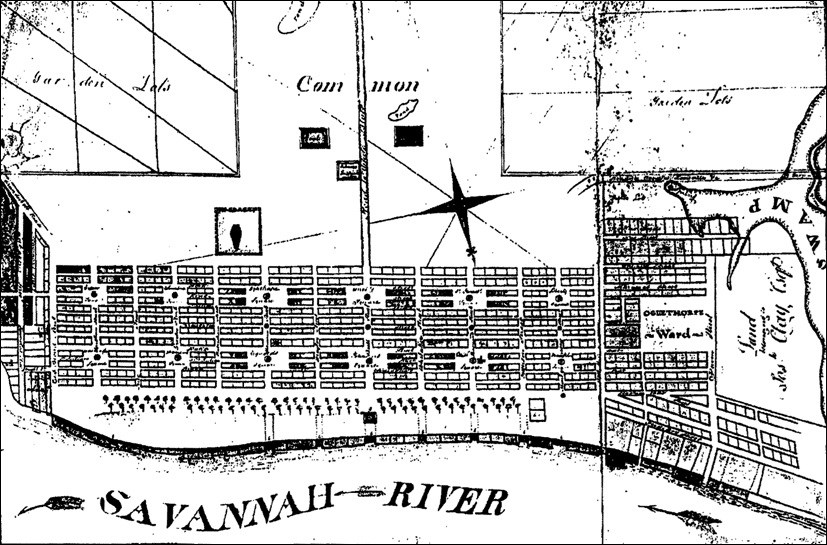

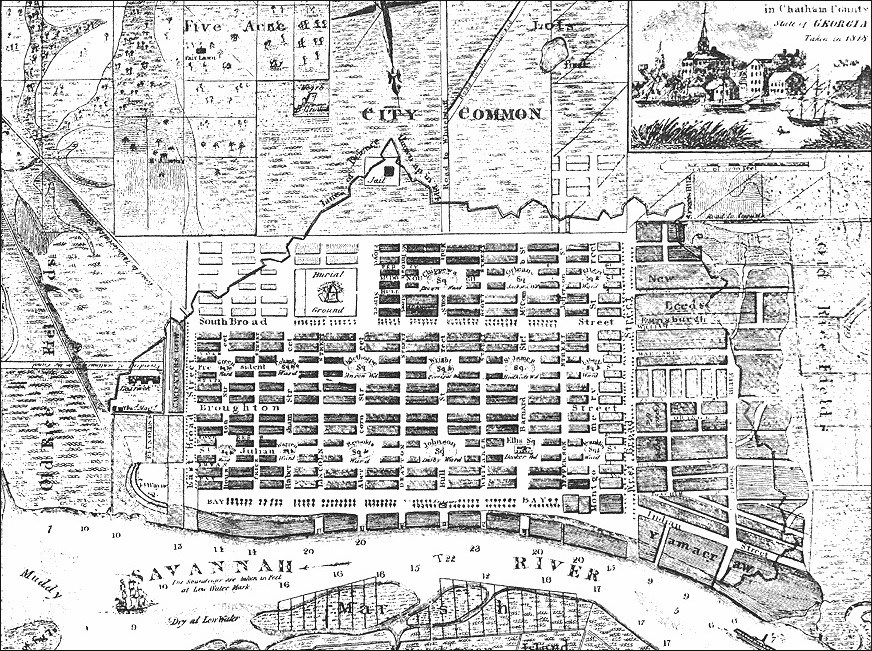

Drawing 3: Savannah, 1800.

Drawing 4: Savannah, 1818.

(Courtesy of the Georgia Historical Society)

By 1800, when Drawing 3 was created, four more wards had been laid out on the eastern side of the town and two more on the western side.

Questions Drawings 3 & 4

1. Use Drawing 1 as a guide to help you locate the original settlement (the first four wards) on Drawings 3 and 4. Has the original ward design changed with the addition of the new wards?

2. Using Drawing 3, find the location of the garden plots. How does the layout of the plots differ from the ward plan of Savannah?

3. Using Drawing 4, find the burial ground. Does this same feature appear on Drawing 3? Why do you think it was located where it was?

4. Locate the compass for Drawing 3 and Drawing 4. Examine the flow markers on the Savannah River in each one. In which direction is the Savannah river flowing?

Visual Evidence

Painting 1: Panorama of Savannah by Fermin Cerveau, 1837.

Questions for Painting 1

1. What are your impressions of Savannah based on this painting? If you did not know when it was painted, what clues might help you narrow down the time period?

2. How does the painting enhance your understanding of Savannah at this time period? Describe why it provides more information than a basic plan.

3. Slightly more than one hundred years separate Drawing 1, made in 1734, and this painting, created in 1837. What are some of the major changes that have occurred in Savannah, as recorded by these two images?

Putting It All Together

The following activities engage students in a number of ways that let them discover how city planning, past and present, relates to their lives.

Activity 1: Draw the City Plan of Savannah

Have students create the basic module of Savannah's town plan--the ward--with all its divisions. Refer them back to Reading 2 and the visual evidence for more information about the makeup of the ward.

There are two sets of instructions depending on level of difficulty desired: first set uses approximate measurements and the second set uses measurements scaled down from the original ward size. Choose I or II. Version II likely will be easier to complete with grid paper or a drawing board and t-square tool.

I. First version of Activity 1, Approximation instructions:

Using the information provided, draw a ward with a pencil and ruler. Start by drawing the geometric square that will be the outline of your ward and then mark divisions along the edges of the square.

Use the following measurements:

A. North and South edges of the ward:

Measure 7 inches wide

Include, in this order from side to side (west to east) along the edge:

-

5 house lots, each ½ inch wide

-

1 Avenue, 2 inches wide

-

5 house lots, each ½ inch wide

B. East and West edges of the ward:

Measure 7 inches wide

Include, in this order from top to bottom (north to south) along the edge:

-

House lot, ¾ inch

-

Street, ¼ inch

-

House lot, ¾ inch

-

Street, ¼ inch

-

Trust lot, ½ inch

-

Avenue, 2 inches

-

Trust lot, ½ inch

-

Street, ¼ inch

-

House lot, ¾ inch

-

Street, ¼ inch

-

House lot, ¾ inch

Note that the first house lot on the north edge and the first lot on the west edge are the same lot. The same is true for the lots in the other three corners – these corner lots each have borders on two of the edges.

After marking the divisions along the edges, students will finish drawing the lots as boxes. Ask students to notice that the avenues divide the ward into quadrants. How many house lots are in each quadrant? How many house lots are there in the entire ward? Students have learned that the house lots are each 60x90 ft, which means each row of house lots in a ward is a 300x90 ft rectangle. The four trustee lots are rectangles each 180x60 ft. Where is the open Square located? Ask students to label the following areas on their maps: Square, Tything, Trust Lot, street, and avenue.

Once students have completed their ward maps, engage them in thinking critically about the advantages and disadvantages of this design. Ask them to write 2-3 paragraphs describing how the ward plan would limit and/or benefit the city's residents in the short and long terms. Would they want to live in a ward? Why or why not? If they were to design a city plan to foster equality among residents, how would their plan be similar to and how would it differ from Savannah’s?

II. Second version of Activity 1, Scaled instructions:

Using the information provided, draw a ward with a pencil and ruler. Start by drawing the geometric square that will be the outline of your ward and then mark divisions along the edges of the square.

The suggested scale for this activity is: 1/8 inch equals 10 feet.

Use the following measurements:

A. North and South edges of the ward:

Measure 675 feet wide

Include, in this order from side to side (west to east) along the edge:

-

5 house lots, each 60 feet wide

-

1 Avenue, 75 feet wide

-

5 house lots, each 60 feet wide

B. East and West edges of the ward:

Measure 675 feet wide

Include, in this order from top to bottom (north to south) along the edge:

-

House lot, 90 feet wide

-

Street, 37 1/2 feet wide

-

House lot, 90 feet wide

-

Street, 22 1/2 feet wide

-

Trust lot, 60 feet wide

-

Avenue, 75 feet wide

-

Trust lot, 60 feet wide

-

Street, 22 1/2 feet wide

-

House lot, 90 feet wide

-

Street, 37 1/2 feet wide

-

House lot, 90 feet wide

Note that the first house lot on the north edge and the first lot on the west edge are the same lot. The same is true for the lots in the other three corners – these corner lots each have borders on two of the edges.

After marking the divisions along the edges, students will finish drawing the lots as boxes. Ask students to notice that the avenues divide the ward into quadrants. How many house lots are in each quadrant? How many house lots are there in the entire ward? Students have learned that the house lots are each 60x90 ft, which means each row of house lots in a ward is a 300x90 ft rectangle. The four trustee lots are rectangles each 180x60 ft. Where is the open Square located?

Ask students to label the following areas on their maps: Square, Tything, Trust Lot, street, and avenue.

Once students have completed their ward maps, engage them in thinking critically about the advantages and disadvantages of this design. Ask them to write 2-3 paragraphs describing how the ward plan would limit and/or benefit the city's residents in the short and long terms. Would they want to live in a ward? Why or why not? If they were to design a city plan to foster equality among residents, how would their plan be similar to and how would it differ from Savannah’s?

Activity 2: Then and Now in Your Town

Few cities in America retain their original design like Savannah. Remind students that their generation will be the next stewards, or guardians, of your town's history. Instruct students to analyze the development of the town in which they live or of one nearby through maps. You may decide to divide them into teams or pairs and coordinate with the local library, historical society, or land records office so that the research facilities are prepared for the students.

1. Each team should locate two maps of the town, one which is current and one that dates to an earlier time period, preferably at least 50 years before the current map.

2. Once the teams have copies of the two maps, ask them to compare the differences in the town as shown in the earlier and later map. Things to consider include:

-

Have open spaces, such as parks, remained constant or have previously natural or open spaces been developed?

-

Has the central area of the town changed?

-

Has the business district changed?

-

Which map has more roads? Explain why.

-

Are there areas where little or no change has taken place?

-

Is the town more developed in the current map than in the historic map?

3. Ask team members to compare the maps as documents, not just for their geographical content. They should compare the style and presentation of information on the two maps, including differences in wording, scale, and compass rose/north indicator.

4. After the teams have shared their findings, ask the class to discuss which areas have changed the most and which have changed the least. Ask them to analyze the pattern of change in their community. What conditions accounted for these changes? What is the present condition of the unchanged areas? Do these areas represent an important part of the town's history and, if so, should they be reserved for future generations? Debate whether the town's historic area could be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places.

Savannah, Georgia: The Lasting Legacy of Colonial City Planning--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Savannah, Georgia: The Lasting Legacy of Colonial City Planning, students will learn about James Oglethorpe and his enduring city plan from the colonial era. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

The Cultural Landscape Foundation is the only not-for-profit foundation in America dedicated to increasing the public’s awareness of the importance and irreplaceable legacy of cultural landscapes. Visit their website for more information on what cultural landscapes are and what they represent. Also learn about endangered landscapes and grassroots efforts to preserve them.

Fort Frederica National Monument

Fort Frederica National Monument is a unit of the National Park System. Visit the park's web pages to better understand this 18th-century planned colonial community in Georgia. Included on the site is an interesting feature about children's lives in colonial times. Students will gain a better understanding of day-to-day life by reading a girl's 1775 journal.

Library of Congress: Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS)/ Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Collection

Search the HABS/HAER collection for detailed drawings, photographs, and documentation from their architectural survey of the Savannah Historic District and the Savannah Victorian Historic District. HABS/HAER is a division of the National Park Service.

Georgia Stories: History Online

Sponsored by Georgia Public Broadcasting, Georgia Stories: History Online provides primary sources such as letters, personal journals, and manuscripts by early settlers, as well as contemporary newspaper and magazine articles, depicting daily life in early Georgia.

Images of Oglethorpe

Armstrong Atlantic State University compiled Images of Oglethorpe from a private collection of a Savannah, Georgia resident. Included on the site are numerous historic images, biographical information on Oglethorpe, and a time line of his life.