Last updated: October 7, 2020

Article

Samuel Ashbow - A Forgotten Casualty of Bunker Hill

by Julia Mize, U.S. Park Ranger

Though the Battle of Bunker Hill was an American defeat, it provided the New England forces an opportunity to define themselves in a way that would remain unique for nearly 175 years. The British army was a professional military comprising mostly volunteers. The British army was also a rather homogeneous group, which stood in stark contrast with the American militias.

The origin of militias has many conjectures, but the militias of the colonial period comprised men and boys (generally 16 to 60 years in age) who were able to “bear arms” and who were organized to protect and defend their town or village. These local militias varied widely in experience, training, leadership and arms. Most importantly, the militias were local and comprised those men who lived in a community. In 1770’s New England, there were many diverse communities.

When the British colonized New England in the 17th century, indigenous people already inhabited the land that would become the colonies. The relationship between these two groups could well be described as “complicated”. Despite wars, broken treaties, diseases and complicated alliances, the Native People remained very much a part of colonial society.

The other non-English group in the colonies were the Africans, brought as slaves, with some remaining so and others winning or buying their freedom. When the Revolutionary War began, many of these bondsmen had the opportunity to win their freedom by bearing arms.

Following the fighting at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress orchestrated an effort to raise an army through its Committee of Safety, and directed all volunteers to Cambridge. Upwards of 16,000 men answered the call, including many members of the Mohegan tribe from Connecticut. Samuel Ashbow Jr. and his brother John were just two of the Patriots of Color who fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill in the first and last fully integrated American army until the Korean conflict.

So, who were these “embattled farmers” who stood against the professional British army? Traditional depictions show them as young, white, clothed in homespun, and carrying a musket and haversack. While many American soldiers did fit that description, many others did not. One case in point is the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, in which approximately 150 of the roughly 2,500 to 4,000 Americans engaged were “Patriots of Color,” or Native Americans and African Americans who fought for their country alongside their white brothers.

Samuel was one of these men. Samuel was a Mohegan Indian from Montville, Connecticut, and one of four brothers who fought and died in the American Revolution. Samuel and his brothers were the sons of Reverend Samuel Ashbow who, along with Samson Occum, were famous ministers in the Mohegan community. Samson’s brother, John Occum, also fought at Bunker Hill.

The Ashbow brothers enlisted in the American cause on May 10, 1775 and marched to Cambridge in Captain John Durkee’s Company with Colonel Israel Putman’s Regiment. They were a part of the some 16,000 militiamen responding to the call for the creation of an army to oppose the British Regulars after the confrontation at Lexington and Concord.

After crossing onto the Charlestown Peninsula on June 17, 1775, twenty-nine year old Samuel and twenty-two year old John were assigned to guard the Rail Fence located perpendicular to the Mystic River, and the site of the first two assaults by British troops attempting to flank the Americans and take the earthen fort on Breed’s Hill. The line at the fence held firm and drove back the Regulars, inflicting horrific casualties upon them. In the end, British Marines and infantrymen stormed the earthen fort, or redoubt, and drove the Americans out and swept over their lines, including the Rail Fence. It is believed Samuel died in this last assault. He was most likely buried in a mass grave by the British victors. The exact location is unknown.

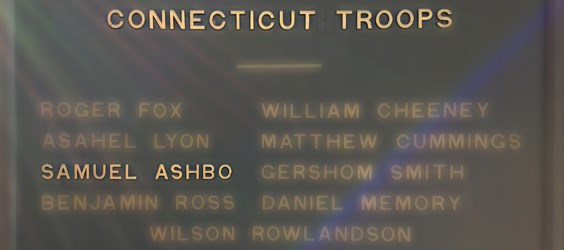

Today, along the Freedom Trail in Charlestown’s Training Field, a series of bronze tablets list the American dead from the Battle of Bunker Hill. Samuel’s name is found under the Connecticut Troops. Samuel, the first Native American to die in the American Revolution, left behind a wife and two year old son. Samuel gave his life to the American cause, but his name and his descendants have been lost in the wind while others have become household names. Why the difference?

Sources & Further Reading:

- Collin G. Calloway, First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011).

- Collin G. Calloway, The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- George Quintal, Jr., Patriots of Color: ‘A Peculiar Beauty and Merit’: African Americans and Native Americans at Battle Road & Bunker Hill (Boston: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, 2004), 53-54.

- John R. Elting, The Battle of Bunker's Hill (Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1975).

- Paul Grant-Costa and Tobias Glaza, eds., The New England Indian Papers Series, Yale University Library Digital Collections, http://findit.library.yale.edu/yipp.