Last updated: July 28, 2023

Article

Saint Gaudens National Historic Site: Home of a Gilded Age Icon(Teaching with Historic Places)

Augustus Saint-Gaudens had been told that this region of western New Hampshire along the banks of the Connecticut River was the "land of Lincolnshaped men." That description drew him to Cornish, New Hampshire, in 1885 to find a place where he could model his latest commission, a statue of Abraham Lincoln. Seeking only a temporary residence and studio, Saint-Gaudens and his wife, Augusta, were directed to an old rundown tavern.

Saint-Gaudens was initially appalled by the place, but his wife saw possibilities. Before long the family established a summer home and studio there. Here in the shadow of nearby Mt. Ascutney, Saint-Gaudens conceived a host of projects. Here he became the leader of the art colony and community that grew around him. And it was here that he battled cancer and sought release and health through vigorous physical activity. In the end, after having operated at the height of his career four studios—one in Paris, two in New York City, and the Cornish site—he would choose to be buried here.

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site is a window into one aspect of the Gilded Age: the role of the artist. The house and grounds reflect what was important to "highbrow" Americans at the turn of the century. For example, the importance of leisure is evident in the gardens and grounds adjoining the Pan Pool and the remnants of the small golf course the artist had built. Not surprisingly, money was another important component of Gilded Age America. Saint-Gaudens was a man who enjoyed the finer things in life and was not necessarily modest in his habits. Although he is known primarily for his 35 public monuments erected across the United States between 1880 and 1907, the vast majority of Saint-Gaudens' works were bas-relief portraits commissioned by private clients.

About This Lesson

The lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site" (with photographs), The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. It was written by James A. Percoco, a social studies teacher at West Springfield High School in Virginia. The lesson was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson plan focuses on patron-commissioned bas-reliefs, the enigmatic Adams Memorial, and the gold coins created by Saint-Gaudens. It can be used to teach units on the Gilded Age or the role of art and artists in society.

Time period: Late 19th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site: Home of a Gilded Age Icon relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801 to 1861)

-

Standard 2C- The student understands how antebellum immigration changed American society.Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States

(1870 to 1900) -

Standard 1A- The student understands the connections among industrialization, the advent of the modern corporation, and material well-being.

-

Standard 1D- The student understands the effects of rapid industrialization on the environment and the emergence of the first conservation movement.

-

Standard 2C- The student understands how new cultural movements at different social levels affected American life.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site: Home of a Gilded Age Icon

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard B - The student describes personal connections to place - as associated with community, nation, and world.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

Theme X: Civic Ideals, and Practices

-

Standard A - The student examines the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

Objectives for students

1) To identify stages in Saint-Gaudens' training and career that established him as the leading American sculptor of the 19th century.

2) To examine how the life, home, and studio of an important American artist reflected traits and values of the Gilded Age in America.

3) To explain the difference between sculpture-in-the-round and bas-relief sculpture.

4) To describe how the growth of the Cornish Art Colony reflected the role of the arts in society.

5) To engage students in looking at their own community for evidence of the visual arts.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-quality version.

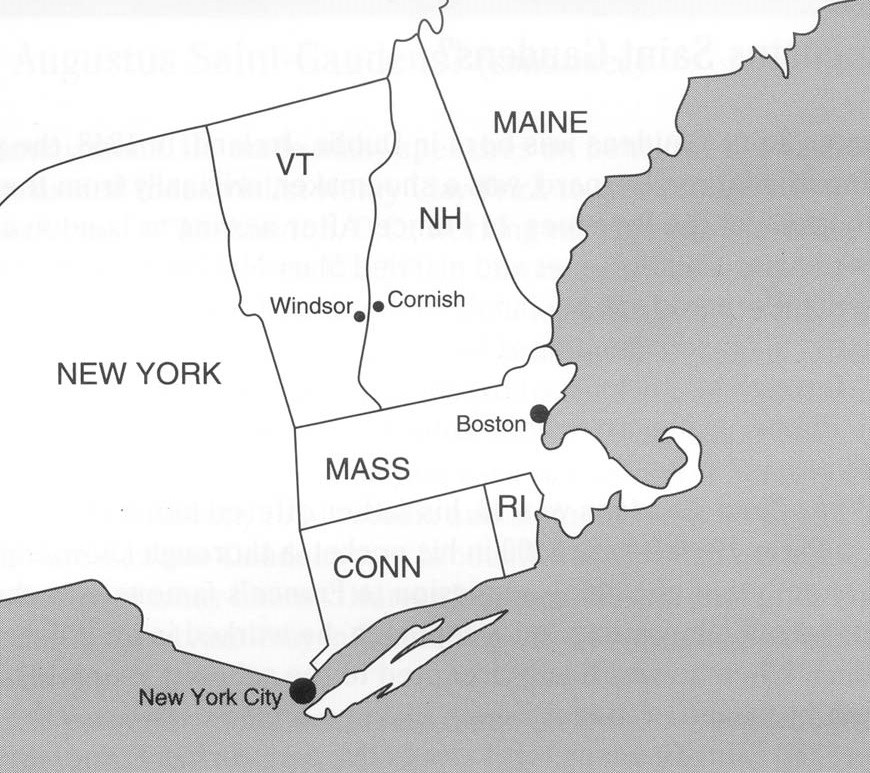

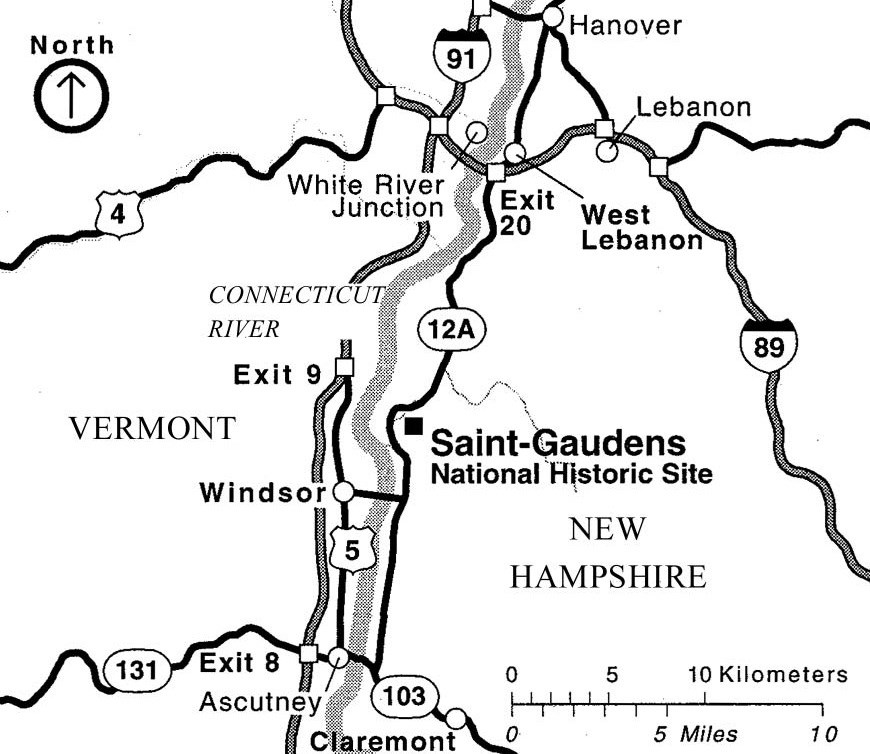

1) two maps of the site and surrounding region;

2) five readings on Saint-Gaudens' life and work;

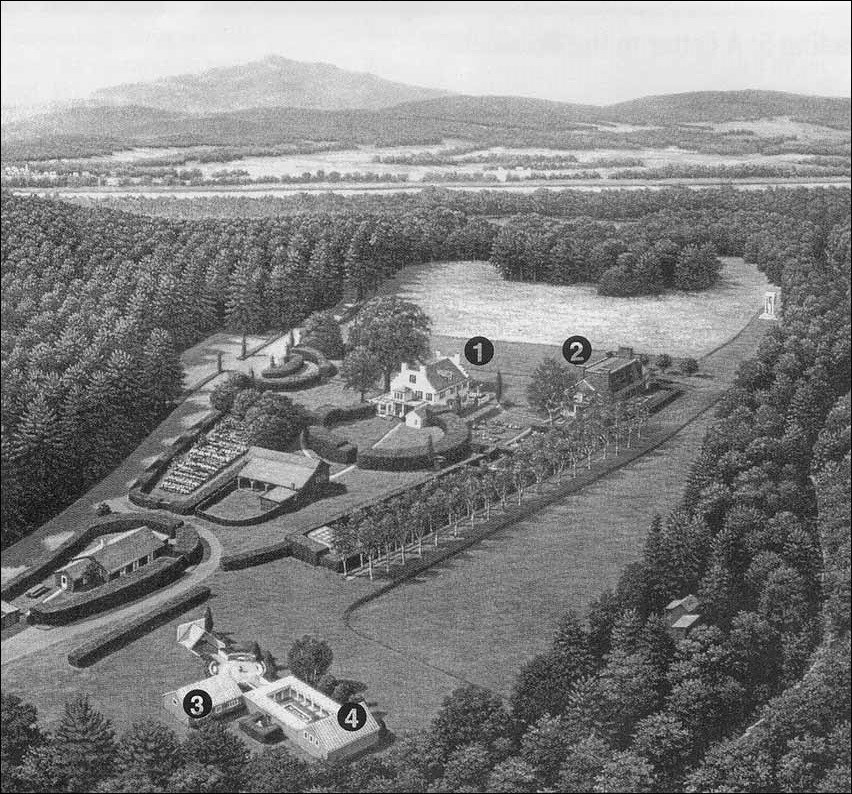

3) one drawing of Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site;

4) six photos of the site and some of Saint-Gaudens' works.

Visiting the site

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, administered by the National Park Service, is located on New Hampshire State Route 12-A in Cornish, New Hampshire. It is 9 miles north of Claremont, New Hampshire, 18 miles south of Hanover, New Hampshire, and 2 miles north of Windsor, Vermont. The site may be reached via the West Lebanon, New Hampshire, exit on U.S. Interstate 89 or the Ascutney or Hartland, Vermont, exits on U.S. Interstate 91. The park is open May through October. For more information, contact the Superintendent, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, R.R. 2, Cornish, NH 03745, or visit the park's Web pages.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Setting the Stage

Some of the leading characteristics of the Gilded Age included growing industrialization, entrepreneurial optimism, Social Darwinism, and materialism. Importance was placed on personal wealth and the ability to live in high style. Patronage—the support of artists through major commissions and wealthy clients—while not new, was an important aspect of the Gilded Age.

The arts of the Gilded Age reflected a changing and emerging nation on the world scene. The creation of public monuments, great and lavish public spaces, and splendidly decorated homes that looked more like palaces demonstrated the growing belief among many Americans that the United States was the heir to the great cultural traditions of Europe. The cultural aspects of the Gilded Age sometimes are referred to as the "American Renaissance." According to architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson, "the artist played a leading role. He could provide a setting of leisured elegance bearing the patina of class and taste for people who were frequently one generation removed from overalls and shovel. Fittingly, the artist designed the currency of capitalism—Augustus Saint-Gaudens did the ten and twenty dollar gold pieces. The artist did not play the avant-garde role, rebelling against society and the inequalities of wealth. Rather he became part of the elite...."¹

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), renowned 19th-century American sculptor, was a member of this elite. His artistic training and talent ensured his place in Gilded Age society. He created nearly 150 sculptures during a career that spanned three decades. His commissions ranged from large public statues to U.S. gold coins to bas-reliefs for prominent private clients.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Cornish, New Hamphsire and the surrounding region.

Questions for Map 1

For a time, Saint-Gaudens maintained two studios in New York City, an apartment and studio in Paris, and a home and studio in rural Cornish, New Hampshire. He came to New Hampshire in 1885 to find a place to model his latest commission, a statue of Abraham Lincoln. He chose the area because he had been told by a friend that it was an area with "plenty of Lincoln-shaped men." He and his family spent summers here from 1885 to 1897.

1. How many studios did Saint-Gaudens operate? What do you think this reveals about his economic and professional status?

2. What would be some of the advantages and disadvantages of an artist maintaining a number of homes and studios?

3. How would you describe the location of Cornish, New Hampshire? Why did Saint-Gaudens choose to open a studio here? What do you think the quote regarding "Lincoln-shaped men" meant?

Locating the Site

Map 2: Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site.

Questions for Map 2

1. Calculate the distance between Windsor, Vermont, and the Cornish estate (now Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site). Note that Windsor is the closest town.

2. What do you think the location of the Cornish estate shows about Saint-Gaudens' life in this area?

3. What do you think were the advantages and disadvantages to living in this area?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Who Was Augustus Saint-Gaudens?

Augustus Saint-Gaudens was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1848, the year of the Potato Famine. His father, Bernard, was a shoemaker, originally from the little village of Aspet in the foothills of the Pyrenees, in France. After moving to London and then on to Dublin, Bernard Saint-Gaudens met and married Mary McGuinness. Six months after the birth of Augustus, Bernard took his family to the United States, settling in New York City. When Augustus finished schooling at 13, he was apprenticed to a French cameo-cutter in New York. (A cameo is a medallion with a profile cut in raised relief.) Through his teens the boy labored long days in his master's shop, and studied nights at the Cooper Union art school. Later he studied at the National Academy of Design near his home.

When Saint-Gaudens was 19, his father offered him a chance to see the Exposition of 1867 in Paris. International exhibitions were extremely popular in the late 19th century, the period of the Gilded Age. Some of these were limited to works of art. In others, such as the World's Columbian Exposition, displays of the latest in industry, commerce, science, and agriculture were the primary focus. The latter, especially, reflected the optimism and faith in human progress characteristic of the era. Competition to exhibit their works at either type of exposition was fierce among artists since inclusion added tremendously to their reputations and their ability to attract clients. Saint-Gaudens left for Paris with $100 in his pocket, a thorough knowledge of his craft, and the greater ambition of gaining admission to France's famous art school, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

While waiting for acceptance, he worked in an Italian cameo-cutter's atelier (studio). When he was finally accepted to the school a year later, he continued to support himself by cameo-cutting.

In 1870 Saint-Gaudens left Paris to live and work in Rome, where he spent the next five years. His outlook and skills matured during these years, and his warm personality attracted both foreign and American friends. His early patrons introduced his name to social circles that mattered. In Rome he also met Augusta F. Homer of Massachusetts, a cousin of painter Winslow Homer.

At age 27 Saint-Gaudens returned to America and began his career with an 1876 commission to design a statue of Civil War admiral David G. Farragut. This commission was a turning point in Saint-Gaudens' life. It brought him both recognition and enough security to marry Augusta Homer. The statue was exhibited in Paris in 1880 and then cast in bronze and placed in Madison Square in New York. According to noted art critic and scholar Lorado Taft, "when in 1881 the Admiral Farragut was unveiled in Madison Square, the work of a new leader was discovered; the foreign and unfamiliar name was henceforth to head the list."¹

After the Farragut statue Saint-Gaudens no longer had to struggle to obtain commissions. These included many of his most famous works, such as the Randall, the Puritan, and the Standing Lincoln, as well as a series of relief portraits (a form of sculpture in which figures protrude from a flat background). The latter in particular revealed his mastery of delicate line and sensitive modeling. In three decades, Saint-Gaudens produced nearly 150 works. These included monumental public sculptures, such as the Shaw Memorial in Boston, the Sherman statue on Fifth Avenue in New York City, and the seated Lincoln in Chicago, as well as those mentioned above. He also completed sculptures-in-the round, such as the Adams Memorial, and numerous bas-reliefs (low reliefs) for private clients. President Theodore Roosevelt personally selected him to design new $10 and $20 gold pieces at the turn of the century.

Saint-Gaudens keenly felt his duties to those who would come after him. As he had benefited from his teachers, so he felt himself obliged to instruct. In numerous private ways he helped aspiring young sculptors. Through the classroom of the Arts Student League he reached many more, teaching steadily from 1888 to 1897. He undertook a new role as leader among his fellow artists by participating in a revolt against the traditions and rules of an older group of artists, and by helping to found the Society of American Artists. He also became a leader of the American group and helped choose American paintings for the 1878 Paris Exposition.

Saint-Gaudens gave generously of his time to other causes as well. He was an adviser to the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 and suggested his former pupil, Frederick MacMonnies, and his friend and contemporary, Daniel Chester French, for important commissions. He made many speeches on behalf of the American Academy in Rome and persuaded industrialist Henry Clay Frick to give $100,000 as an endowment. He later spent much time in Washington, D.C., working with his friends, architects Charles McKim and Daniel Burnham, on the MacMillan Commission for the preservation and development of the nation's capital. The commission's work resulted in the present design of the national Mall, its set-back museum buildings, and the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials.

At the turn of the century, Saint-Gaudens' statue of William Tecumseh Sherman won the Grand-Prix in the Paris Salon of 1900. It was while in Paris that Saint-Gaudens learned of the malignancy which sent him back to Boston for surgery and led to his decision to return permanently to his studio and summer home in Cornish, New Hampshire. Despite his illness, Saint-Gaudens was productive in Cornish between 1900 and 1907 and continued to earn many honors. Harvard, Princeton, and Yale granted him honorary degrees, and both the Royal Academy in London and the French Legion of Honor elected him as a member.

Treatments could not arrest Saint-Gaudens' illness and his health continued to decline. He also weathered other setbacks, such as the fire that destroyed his large studio in 1904. He rebuilt the studio the next year and employed a number of assistants, whom he personally supervised. His productivity never faltered, even though he required a special sedan to move around and the constant attention of a trained nurse. By early 1907 Saint-Gaudens was bedridden but still cheerful. A few days before his death on August 3, 1907, he lay watching the sun set behind Mount Ascutney. "It's very beautiful," he said, "but I want to go farther away."

Questions for Reading 1

1. How did Saint-Gaudens receive his first training in sculpture? How do you think this training might have affected his later work?

2. Where did Saint-Gaudens receive his academic training?

3. What are some of Saint-Gaudens' better known public monuments? How many sculptures did Saint-Gaudens produce during his life?

4. Why do you think President Theodore Roosevelt asked Saint-Gaudens to design coins for the United States?

5. Was Saint-Gaudens influential in the art world? How can you tell? Why do you think the expositions would have been important?

Reading 1 was compiled from the National Park Service's visitor's guide for Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site.

¹ Lorado Taft, Modern Tendencies in Sculpture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1921), 97.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Arrival at Cornish

In his autobiography Saint-Gaudens described his arrival in Cornish, New Hampshire:

Now let me turn to other pleasures, and among them to my coming in 1885 to Cornish, New Hampshire, or Windsor, Vermont, as it is often called since that is the town in which we obtain our mail. For this coming made the beginning of a new side of my existence. I had been a boy of the streets and sidewalks all my life. So, hitherto, although no one could have enjoyed the fields and woods more heartily than I when I was in them for a few days, I soon tired and longed for my four walls and work. But during the first summer in the country, I was 37 at the time, it dawned upon me seriously how much there was outside my little world. We hit upon Cornish because, while casting about for a summer residence, Mr. C.C. Beaman told me that if I would go up there with him, he had an old house which he would sell me for what he paid for it, five-hundred dollars. However, all this side of life was so secondary to my work at that time that I refused to assume any responsibility of the kind, insisting that I was not wealthy enough to spend that amount. Especially was this feeling active when I first caught sight of the building on a dark, rainy day in April, for then it appeared so forbidding and relentless that one might have imagined a skeleton half-hanging out of the window, shrieking and dangling in the gale, with the sound of clanking bones. I was for fleeing at once and returning to my beloved sidewalks of New York. But as Mrs. Saint-Gaudens saw the future of sunny days that would follow, she detained me until Mr. Beaman agreed to rent the house to me at a low price for as long as I wished.

To persuade me to come, Mr. Beaman had said that there were "plenty of Lincoln-shaped men up there." He was right. So much for the first summer. But as the experiment had proved so successful, I had done a lot of work, and I was so enchanted with the life and scenery, I told Mr. Beaman that, if his offer was still open, I would purchase the place under the conditions he originally stated. He replied that he preferred not, as it had developed in a way far beyond his expectations, and as he thought it his duty to reserve it for his children. Instead he proposed that I rent it for as long as I wished on the conditions first named, which were most liberal. But the house and the life attracted me until I soon found that I expended on this place, which was not mine, every dollar I earned, and many I had not yet earned, whereas all of my friends who had followed had bought their homes and surrounding land. So I explained to Mr. Beaman that I could not continue in this way, and that he must sell to me, or I should look elsewhere for green fields and pastures new. The result was that for a certain amount and a bronze portrait of Mr. Beaman, the property came to me.

As I have said, despite its reputation, my dwelling first looked more as if it had been abandoned for the murders and other crimes therein committed than as a home wherein to live, move, and have one's being. For it stood out bleak, gaunt, austere, and forbidding, without a trace of charm. And the longer I stayed in it, the more its puritanical austerity irritated me, until at last I begged my friend Mr. George Fletcher Babb, the architect: "For mercy's sake, make this house smile, or I shall clear out and go elsewhere!" This he did beautifully, to my great delight. Inside he held the ornament of one or two modest mantels, which seemed pathetic in their subdued and gentle attempt at beauty in the grim surroundings, while outside, as our idea was to lower and spread the building, holding it down to the ground, so to speak, I devised the wide terrace that I know was a serious help for, before its construction, you stepped straight from the barren field into the house. As it is now, my friend, Mr. Edward Simmons, of multitudinous and witty speeches declares that it "looks like an austere, upright New England farmer with a new set of false teeth...."

Questions for Reading 2

1. Why did Saint-Gaudens agree to rent and then buy this property if he was initially appalled at the place?

2. What was unusual or different about the terms of sale that Saint-Gaudens made with Mr. Beaman? Do you think a sale such as this could be enacted in American society today? Why or why not?

3. What was it about the house that Saint-Gaudens did not like at first? How did he ask the architect to change it?

Reading 2 was excerpted from Homer Saint-Gaudens, ed. The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, vol. 1 (New York: The Century Company, 1913).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Cornish Colony

The arrival of Saint-Gaudens to Cornish, New Hampshire, in the summer of 1885 marked the beginning of the Cornish Colony. He brought three assistants to work with him in the barn studio: his brother, Louis Saint-Gaudens, Frederick MacMonnies, and Philip Martiny. They were the first in a long series of helpers, many of whom went on to important careers of their own.

That first summer, a friend and painter, George de Forest Brush, also came to Cornish and camped with his wife near the ravine just below the house. Brush had lived out west among American Indians for many years, and the tepee he built for a summer dwelling greatly amused Saint-Gaudens and his neighbors. The next spring Thomas W. Dewing, another painter, rented a house nearby. As the scenic attractions of Cornish became more widely known, that small group began to grow. Other artists found Cornish a delightful spot in which to spend a rural summer working among congenial spirits.

This circle of talented individuals drew others from moneyed and social circles. Italianate villas rose on hillsides and in abandoned pastures. Embellished with sunken gardens, marble fountains, and artfully developed villas, a farm community turned into what local people sometimes called "Little New York." The swirl of this upper-class Bohemia was lively and elegant, but Thomas Dewing said there were "too many picture hats" and tennis rackets, and left to seek a more secluded spot in the backwoods of Maine.

In 1905 the Cornish Colony celebrated the 20th anniversary of the sculptor’s coming to Cornish by holding a masque (a play based on early Greek drama) at the foot of the field below the house. Seventy members of the colony worked together to provide the music, settings, costumes, scripts, and acting for an audience of more than twice that number. A small Greek temple was erected in the grove of large pines that once stood there. Originally made of plaster, it was later reproduced in marble and became the family burial place.

Today the artists who made up the Cornish Colony are gone, and with them a colorful era has passed. But at Saint-Gaudens’ home, now preserved as Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, the well-kept house, carefully designed gardens, and studios still conjure up images of a bygone age--an age that nurtured and enchanted a singular company of artists at Cornish.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Who was the most important member of the Cornish Colony?

2. What type of people made up the Cornish Colony over the years? What attracted them to this New England town?

3. Why do you think all of these artists and writers chose to spend their summers living and working in the same place?

4. How did the presence of the Cornish Colony change the community? What did local residents call the colony? Why?

5. What was the 1905 masque? Why was it held?

Reading 3 was compiled from the National Park Service’s visitor’s guide for Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site.

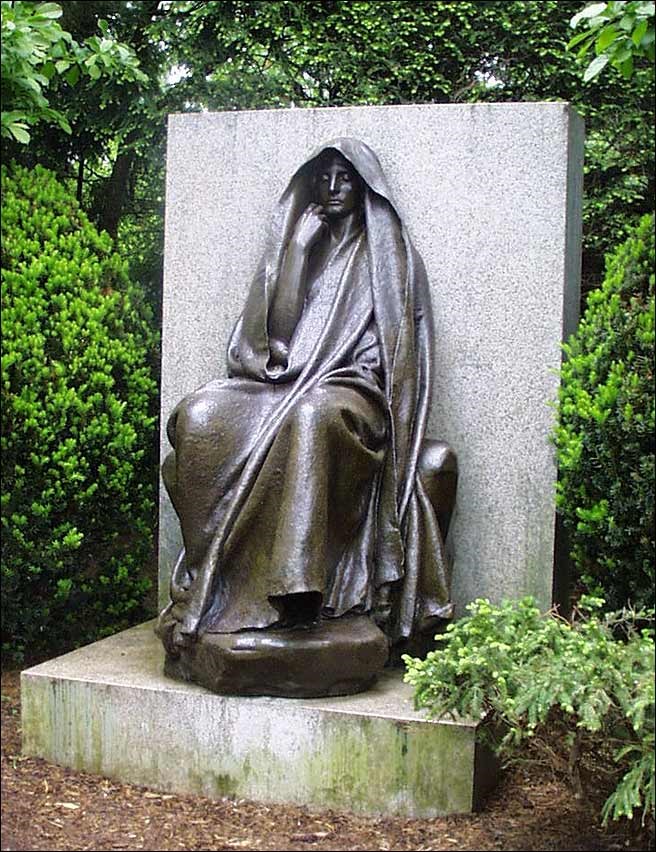

Reading 4: Henry Adams' Reflection on the

Adams Memorial

Writing in the third person, Henry Adams described his reaction to the statue he had commissioned in 1891 as a memorial to his wife, who had committed suicide:

...His first step, upon returning to Washington, took him out to the cemetery known as Rock Creek, to see the bronze figure which St. Gaudens had made for him in his absence. Naturally every detail interested him, every line, every touch of the artist, every change of light and shade, every point of relation, every possible doubt of St. Gaudens’ correctness of taste or feeling; so that, as the Spring approached, he was apt to stop there often to see what the figure had to

tell him that was new, but in all that it had to say, he never once thought of questioning what it meant. He supposed its meaning to be the one commonplace about it—the oldest idea to human thought....The interest of the figure was not in its meaning but in the response of the observer. As Adams sat there, numbers of people came, for the figure seemed to have become a tourist fashion, and all wanted to know its meaning. Most took it for a portrait-statue, and the remnant were vacant in the absence of a personal guide. ...The only exceptions were the clergy, who taught a lesson even deeper. One after another brought companions there, and, apparently fascinated by their own reflection, broke out passionately against the expression they felt in the figure of despair, of atheism, of denial. Like the others the priest saw only what he brought. Like all great artists, St. Gaudens held up the mirror and no more.

Questions for Reading 4

1. Who wrote this reflection?

2. As a client, was Adams satisfied with the work of Saint-Gaudens as embodied in the Adams Memorial? How can you tell?

3. What did Adams say about the meaning of the work?

4. What did Adams mean by saying that Saint-Gaudens held up a mirror? Do you agree with Adams that that is the role of "great artists"?

Reading 4 was excerpted from Homer Saint-Gaudens, ed. The Reminiscences of Augustus-Saint Gaudens, vol.1 (New York: The Century Company, 1913).

Determining the Facts

Reading 5: A Letter to the President

President Theodore Roosevelt, a friend of Saint-Gaudens, personally selected the artist to design $10 and $20 gold coins for the U.S. currency. Saint-Gaudens and the president differed as to the design image. In the end, Saint-Gaudens won, but he never lived to see what numismatists argue are the most exquisite coins minted in U.S. history.

November 11, 1905

Dear Mr. President:

You have hit the nail on the head with regard to the coinage. Of course the great coins (and you might almost say the only coins) are the Greek ones you speak of, just as the great medals are those of the fifteenth century by Pisanello and Sperandio. Nothing would please me more than to make the attempt in the direction of the head of Alexander....

Up to the present I have done no work on the actual models for the coins, but have made sketches, and the matter is constantly in mind. I have about determined on the composition of one side, which would contain an eagle very much like the one I placed on your [inaugural] medal, with an advantageous modification. On the other side would be some kind of a (possibly winged) figure of Liberty striding energetically forward as if on a mountain top, holding aloft on one arm a shield bearing the stars and stripes with the word "Liberty" marked across the field, in the other hand perhaps a flaming torch; the drapery would be flowing in the breeze. My idea is to make it a living thing and typical of progress....

Questions for Reading 5

1. Why do you think Saint-Gaudens wrote this letter to President Roosevelt?

2. What was Saint-Gaudens' vision for the design of these coins?

3. If you were an artist, would you want to design coins? What would be the advantages?

4. Do you agree that it was fitting for Saint-Gaudens to design coins used during the Gilded Age? Why or why not?

Reading 5 was excerpted from Homer Saint-Gaudens, ed. The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, vol.2 (New York: The Century Company, 1913).

Visual Evidence

Drawing 1: Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site.

(1) Aspet, (2) Little Studio, (3) Picture Gallery, (4) New Gallery and Atrium.

Saint-Gaudens made extensive changes to both the house, which was in a dilapidated condition when he first moved in, and the landscape.

Questions for Drawing 1

1. What are your first impressions of the site?

2. Describe the landscape of the grounds and the surrounding region.

3. Locate the main house. Why do you think Saint-Gaudens named the house "Aspet"? (You may need to refer back to Reading 1.)

4. Locate the Little Studio that Saint-Gaudens converted from an old barn. By 1902 he had constructed a larger studio that no longer stands, but was located near the site of the present day New Gallery. Why might Saint-Gaudens have needed more than one studio?

5. Does this look like a summer home? What do you think the site reveals about the lifestyle of the Saint-Gaudenses?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Huggins' Folly.

Photo 2: Aspet today.

Photo 1 depicts the house prior to occupancy by the Saint-Gaudenses, when it was called "Huggins' Folly." Photo 2 shows the house after it restoration by the National Park Service in 1980.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Does the first photo look the way you thought it would based on the description in Reading 2? Why or why not?

2. Do you agree with Saint-Gaudens that the house as it appears in Photo 1 looks "bleak, gaunt, austere and forbidding"? Why or why not? What does Saint-Gaudens' opinion tell you about expectations for the lifestyle of successful people during the Gilded Age?

3. What are the major changes that have taken place with the structure between Photos 1 and 2? Why would a friend of Saint-Gaudens have said that the house looked like it had false teeth?

4. Do you think these changes accomplished what Saint-Gaudens wanted? What can these photos tell you about the taste of the Saint-Gaudenses?

5. Does Photo 2 look like the home of an important artist? What would have been your reaction as a client driving up to this house?

Visual Evidence

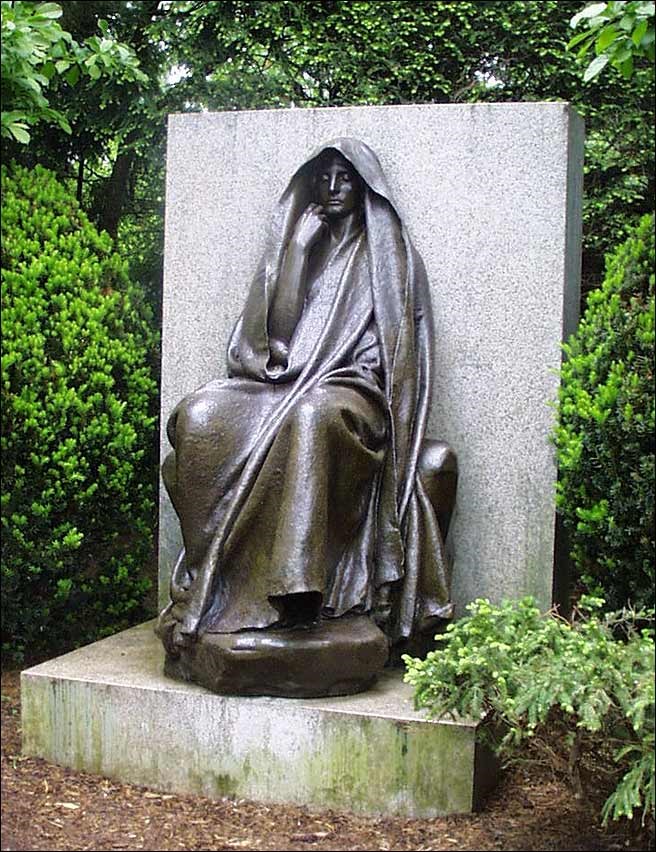

Photo 3: Adams Memorial, 1891, by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), Bronze (cast 1969).

Questions for Photo 3

1. Describe what you see. Is this figure male or female? What activity does the figure seem to be engaged in?

2. What feeling does this piece evoke in you? What idea or concept might this piece represent?

3. What is your opinion of the work?

4. What would you name this sculpture?

5. Viewers and critics never have been able to agree on the meaning of this work. Unlike many clients, Henry Adams gave Saint-Gaudens only general suggestions on how to design this memorial. Adams wanted a figure that reflected compassion, contemplation, and acceptance of the inevitable. Do you think Saint-Gaudens' figure succeeds in conveying those qualities?

6. After the statue's completion, Adams called it The Peace of God, but it also has become well known as Grief, a name attributed to it by Gilded Age author Mark Twain. Do you think either of these names is appropriate? Is one better than the other? How similar or different are their names for the memorial?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Samuel G. Ward, by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

(Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site)

Questions for Photos 4

1. How would you define "bas-relief" based on this image? How is this form of sculpture different from the Adams Memorial?

2. Who is the person in the bas-relief? What might the bas-relief indicate about the nature of this person?

3. What inscriptions or markings can you read on the bas-relief?

4. Does this image look realistic? What is your opinion of the work?

5. How does a bas-relief differ from a photograph? a painting?

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Saint-Gaudens' preliminary model for

$20 gold piece.

Photo 6: Saint-Gaudens' $20 gold piece.

(Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site)

Questions for Photos 5 & 6

1. What observations can you make about the early model?

2. What changes were made between the model and the finished product? What might account for these changes?

3. Does the finished coin appear to satisfy the criteria Saint-Gaudens outlined in his letter to President Roosevelt?

4. How would you describe the finished coin?

5. How are a bas-relief sculpture and a coin similar?

6. Take out a coin and compare the images of today's coins to the coins designed by Saint-Gaudens. How are they alike? How are they different? Do you recognize any of the people on the coins? What symbolic images do you notice?

Putting It All Together

The following activities engage students in a number of ways that let them discover how the sculptor or sculpture relates to the world around them.

Activity 1: Artist and Client

Have students pair up, with one student representing a client and the other student playing the role of artist. Give each pair one pound of modeling clay, which the artist will use to design and create a sculpture that will meet the needs of the patron (client). In consultation with the artist, the client should select a subject for the work. This could be a portrait of the client, a friend, family member, pet, admired hero, or celebrity. Or the sculpture might be symbolic of a concept such as liberty, freedom, justice, valor, good sportsmanship, citizenship, etc. The client may establish criteria for the work (a bas-relief, bust, or full figure; whether the person is holding anything; whether the sculpture is figurative or abstract; etc.), or may leave the design entirely to the artist. If the sculptor is to create a portrait of someone he or she does not know, then the client should bring a photograph.

Once the patron and sculptor have agreed upon a subject, then the artist should withdraw to create the work. Once the sculpture is finished, have the artist and client get back together to discuss the completed work. Is this what the client had in mind? Why or why not? Did the artist feel the client's guidance was clear? Are they both pleased with the results; both displeased; one satisfied and one not? Have the pairs share their works with the rest of the class.

Finally, hold a full class discussion about the pros and cons of the artist-client relationship. What effect does that relationship have on the type of art produced? How does that art illustrate the values of society? What other options are there to financially support artists? What impact does each of those options have on artistic freedom of expression?

Activity 2: Coins, Coins, Coins

Have students examine again the images of the $20 gold piece designed by Saint-Gaudens. Remind them that coins usually depict individuals or symbols that are important to the identity, accomplishments, goals, or ideals of the country that created them. Ask them to sketch a coin that they would like to see circulated around the United States. Remember that they must sketch two sides. Have the students share their sketches with the class and explain why they chose the images and symbolism they used.

Activity 3: Meet the Cornish Colony

Provide students with the following list of names of people who came to live at the Cornish Colony. In order to help the class more fully understand the influence of the Cornish Colony on the world of arts and letters, ask students to pick one of the names, conduct research on that person, and write a short biography. Select some of the biographies and ask the authors to read them aloud to the class.

|

Herbert Adams |

|

Charles A. Platt |

Activity 4: Exploring the Artist's World

Have students conduct further research on the life of Saint-Gaudens, the Cornish Colony, or American sculpture in general, and prepare an oral report for the class. Possible sources include: Burke Wilkinson, Uncommon Clay: The Life and Works of Augustus Saint Gaudens (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985); Louisa Hall Tharp, Saint-Gaudens and The Gilded Age (Boston: Little, Brown, 1969); John H. Dryfhout, The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1982); and A Circle of Friends (Durham: University of New Hampshire, 1985).

Activity 5: Local Wonders

Have students identify and complete research on monuments in their own community. A good place to start looking for information might be a local historical society or public library. As part of their investigation students should conduct research on the origin and purpose of the sculpture, as well as learn about the artist. If possible, students should visit and photograph the monument. As part of the classroom follow-up to their research students should compare the imagery, style, and power to evoke emotion, realism, or symbolism with the type employed by Saint-Gaudens.

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site: Home of a Gilded Age Icon--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site: Home of a Gilded Age Icon, students will learn about a famous artist and his life during the Gilded Age. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Saint-Gaudens Resources:

Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site

Saint-Gaudens National Historic site is a unit of the National Park System. The park's Web pages are an excellent resource for information about Saint-Gaudens' life and works.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress's "American Memory" collection is an excellent source for documents and images. Students can search Touring Turn-of-the-Century America: Photographs from the Detroit Publishing Company, 1880-1920 for images of Saint-Gaudens' works.

Gilded Age Resources:

Ohio State University

The Ohio State University's History Department maintains a web page featuring Cartoons of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Students can use this resource to understand some of the political and social issues of the Gilded Age.