Last updated: January 23, 2024

Article

Robert A. Bell Post, 134, G.A.R.

The following article was originally published on Smith Court Stories, a digital classroom for teachers and students. Please visit the digital classroom for more articles about the Community of Smith Court.

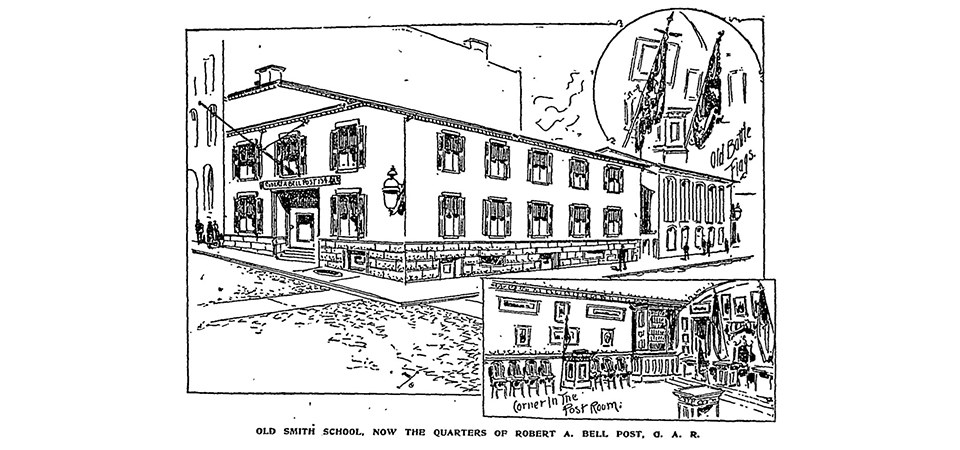

In addition to the African Meeting House serving as a recruitment center for the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment, Smith Court had another connection to the Civil War. In 1877, Boston’s Committee on Public Buildings recommended that the city lease the Smith School at 46 Joy Street to the Robert A. Bell Post, 134, of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). Once approved, the former schoolhouse became the headquarters for this G.A.R. unit of African American veterans at the cost of $1 a year.[1]

Daily Boston Globe, October 9, 1900.

Posts of the Grand Army of the Republic formed across the country to foster community among veterans of the Union Army. Newspapers from the time widely regarded the Robert A. Bell Post, 134, chartered June 29, 1870, as the first all-Black G.A.R. post in the country.[2] Veterans of this post served with the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, the 55th Regiment, and the Massachusetts 5th Cavalry. This post’s notable members included abolitionist Lewis Hayden, who recruited men for the 54th, and Medal of Honor recipient Sergeant William Carney.[3]

African American veterans formed over 200 all-Black posts across 24 states; many of the posts located in cities had over one hundred members.[4] While some historians suggest the distinction between all-White and all-Black posts demonstrated segregation in the G.A.R., historian Barbara Gannon contends that these posts served a similar role as Black churches, functioning as crucial centers of African American communities. She further argues that they formed out of a desire “to serve their local community and as part of a broader agenda: to challenge the notion of an all-white Civil War.”[5] The history and work of the Robert A. Bell Post, headquartered on Smith Court, support her claim.

Women frequently created auxiliary posts to support the veterans.[6] Some all-Black posts had Ladies of the G.A.R. (L.G.A.R.) formed by women related or married to veterans. Other posts, such as the Robert A. Bell Post, 134, had a Woman’s Relief Corps (W.R.C.), whose members had to demonstrate their loyalty and devotion to the veterans and their cause.[7] At an 1890 event, President of the Woman’s Relief Corps, 67, Mary L. Hammond expressed this relationship:

We have always felt it our duty to aid Robert A. Bell Post. It is the woman’s duty to stand by the defenders of the country. When our country was in peril, although we could not shoulder the musket and march to the front to give our lives for the dear old flag, at home we plied our needs, thought and worked to cheer the boys in blue, who were fighting to preserve the Union. But some of us did go to the front, and in the hospitals we gave encouragement to the wounded, sick and dying.[8]

The Robert A. Bell Post, aided by its Woman’s Relief Corps, played a significant role in supporting African American Civil War veterans, their families, and the local Black community. Members of this post held true to the G.A.R.’s three principles: fraternity, charity, and loyalty.[9] These principles guided the Post as it sponsored events at its Smith School headquarters.

Fraternity

To uphold fraternity, the Robert A. Bell Post, 134 held meetings, anniversary celebrations, and entertainment activities to encourage community among their comrades. At these events, Post members sang songs, gave speeches, played instruments, and read poems to commemorate their experiences in the war.[10] The strong sense of community within the Post led to the headquarters serving as the setting for major life events, such as weddings, anniversary celebrations, and funerals.[11]

The Bell Post also hosted gatherings known as "campfires," which proved popular among G.A.R. posts across the country as well as for members of the Bell Post. Historian Barbara Gannon described how these events, “rarely held around campfires or even outdoors, involved storytelling, songs, speeches – both serious and humorous – and other reminiscences of the joys and anguish of military life.”[12] Boston newspapers shared the activities of these campfires during which members gave speeches “amid the smoke of clay pipes.”[13] These events generally lasted well into the evening as the veterans reminisced about their wartime experiences.

Northeast Museum Services Center, National Park Service

Charity

Across the G.A.R., Woman’s Relief Corps and Ladies of the G.A.R. focused mostly on this pillar, especially African American groups who recognized the poverty and social needs of their communities.[14] Commander of the Bell Post Joseph H. Smith expressed his gratitude to the W.R.C. for playing this role at an event in 1890:

We thank God that Post 134 has a Woman’s Relief corps. You have, during the past year, nobly assisted us in many ways. Notably with money. And you are still at work thinking and planning how to assist us in raising money to entertain our comrades.[15]

To raise money for its charity fund, the Bell Post and the W.R.C. hosted fairs, musicals, "literary entertainments," and picnics at the hall at the Smith School and other nearby locations.[16] These events, filled with songs, dancing, games, and food, helped the Bell Post support the needs of its members, their families, and the local community.

Loyalty

Arguably the most important principle of the G.A.R., loyalty encouraged members to demonstrate their patriotism to their country and allegiance to the memory of the Civil War.[17] They achieved these goals through participation in Memorial Day exercises and actively fighting against racial injustices. They also saw themselves as challenging the myth of the "Lost Cause," the distorted belief that slavery and race did not play a central role in the Civil War and that romanticized the South and the Confederate war effort.[18]

For decades, the Robert A. Bell Post recognized their comrades through ritualistic Memorial Day (formerly Decoration Day) exercises. A May 31, 1906 Boston Daily Globe article described one such commemoration. The day began with the Post organizing for breakfast at its Smith School headquarters.[19] Then members of the Bell Post walked down to City Wharf to take a ferry to Rainsford Island. At the island, the veterans “placed floral tributes on the graves of 110 comrades.”[20] On the ferry ride back to the city, the Woman’s Relief Corps threw flowers into the harbor to honor unknown soldiers.[21] Before returning to their headquarters, the members of the Bell Post participated in Memorial Day exercises at the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Memorial.[22]

Other veterans’ groups joined the Bell Post in these exercises throughout the years. The Shaw Guards and the Sergeant William H. Carney Camp, 82, Sons of Veterans, sometimes escorted the Robert Bell Post as they marched to City Wharf.[23] In the 20th century, newspapers also noted the involvement of the William H. Carney Circle, Ladies of the G.A.R., and the William E. Carter Post, American Legion, in these events.

The 1930s marked the last years of the Bell Post’s participation in Memorial Day exercises. In 1933, the Post made its last trip to Rainsford Island Cemetery on Memorial Day.[24] The following year, William Jackson, commander of the Bell Post and one of the last three remaining members of the Post, participated in the exercises at the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Memorial “attired in his brass-buttoned blue uniform and his black campaign hat of other days.”[25]

Reverend Dr. E. George Biddle (94), the last remaining member of the Robert A. Bell Post, 134, served as "the guest of honor at impressive exercises in honor of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry" at the 1939 Memorial Day exercises, becoming the last member to do so.[26]

These Memorial Day commemorations not only honored the sacrifices of Black soldiers in the Civil War, but they also inspired social action to combat the lingering effects of slavery and racism throughout the country. Historian Lois Brown described how African Americans at the end of the 19th century used Memorial Day events to shed light on racial discrimination. She stated:

Fueled by African American patriotism, chapters like the Robert A. Bell Post 134 used Memorial Day events to protest Southern lynchings and to prepare a collective black urban response to Southern mob violence.[27]

For example, at the 1936 Memorial Day event, the Bell Post joined other Black veterans in speaking out against the Ku Klux Klan’s militant and violent offshoot the "Black Legion" "for what they considered the misuse of the word ‘black’ and for its aims."[28]

46 Joy Street played a central role in the Black community as the headquarters of the Robert A. Bell Post throughout the Post's years of activity. The building served as the gathering and event space for the Post’s various events aimed at fulfilling the pillars of the G.A.R.: fraternity, charity, and loyalty.

Footnotes

[1] “Leasing the Smith School,” Boston Globe, Sept. 7, 1877.; “Acted On in Concurrence,” Boston Globe, Oct. 8, 1886.; “Passed in Concurrence,” Boston Globe, Sept. 9, 1887.

[2] "National GAR Records Program - Historical Summary of Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Posts by State - Massachusetts," Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, http://www.suvcw.org/garrecords/garposts/ma.pdf; “Deeds of Colored Heroes Retold,” Boston Globe, June 30, 1936.; “Smoke Talk of Robert A. Bell Post,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1895.; “Oldest Colored Post,” Boston Globe, June 30, 1892.

[3] Lois Brown, Pauline Hopkins: Black Daughter of the Revolution (United States: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 164; William A. McEvoy Jr. & Robin Hazard Ray, “Rainsford Island: A Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect and Private Activism,” https://mountauburn.org/wp-content/uploads/Rainsford-Island-5-16-2020-pdf-1.pdf, 102.

[4] Barbara A. Gannon, The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic (United States: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 39.

[5] Gannon, The Won Cause, 37, 40.

[6] Gannon, The Won Cause, 47.

[7] Gannon, The Won Cause, 48.

[8] “Relics for the Bell Post,” Boston Daily Globe, July 11, 1890.

[9] Gannon, The Won Cause, 35.; "Introduction," The Grand Army of the Republic and Kindred Societies, Main Reading Room, Library of Congress, accessed June 2020, https://www.loc.gov/rr/main/gar/garintro.html

[10] Gannon, The Won Cause, 35.; "Introduction," The Grand Army of the Republic and Kindred Societies, Library of Congress.

[11] “Young-Howard,” Boston Globe, Sept. 29, 1893.; “Wedded Twenty-five Years Ago,” Boston Globe, Sept. 17, 1889.; “Funeral of Private Officer,” Boston Globe, Apr. 1, 1892.; “Funeral of Justin Granby,” Boston Globe, Aug. 21, 1893, 6.

[12] Gannon, The Won Cause, 35.; "Introduction," The Grand Army of the Republic and Kindred Societies, Library of Congress.

[13] “Bell Post Veterans Imitate War-Time Festivities,” Boston Globe, Apr. 2, 1889.

[14] Gannon, The Won Cause, 48.; "Introduction," The Grand Army of the Republic and Kindred Societies, Library of Congress.

[15] “Relics for the Bell Post,” Boston Daily Globe, July 11, 1890.

[16] “In Aid of Charity Fund,” Boston Daily Globe, Apr. 17, 1900.; “R.A. Bell Post Entertainment,” Boston Globe, May 17, 1887.

[17] Gannon, The Won Cause, 36.; "Introduction," The Grand Army of the Republic and Kindred Societies, Library of Congress.

[18] Matthew Wills, "Origins of the Confederate Lost Cause," JSTOR Daily, July 15, 2015, https://daily.jstor.org/origins-confederate-lost-cause/.

[19] “Exercises at the Shaw Memorial,” Boston Daily Globe, May 31, 1906.; “Trip to Rainsford Island,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1896.

[20] “Exercises at the Shaw Memorial,” Boston Daily Globe, May 31, 1906.

[21] “Exercises at the Shaw Memorial,” Boston Daily Globe, May 31, 1906.

[22] “Exercises at the Shaw Memorial,” Boston Daily Globe, May 31, 1906.

[23] “May Concert on Joy Street,” Boston Globe, May 23, 1889.

[24] McEvoy and Ray, “Rainsford Island,” 114.

[25] "Whilrling Hub," Baltimore Afro-American, June 9, 1934.; “Only One of Bell Post is Able to Join Shaw Memorial Rites,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1934.

[26] Quote from Boston Globe, May 31, 1939 as stated in McEvoy Jr. and Ray, “Rainsford Island,” 114.

[27] Brown, Pauline Hopkins, 165.

[28] “Negro Veterans Hit ‘Black Legion,’” Boston Herald, May 31, 1936.