Last updated: October 28, 2024

Article

Restoring the Landscape at Fort Necessity

The historic tree line is important to the battle at Fort Necessity. The French soldiers fired on the fort from behind trees instead of coming out into the open. George Washington reported that during the battle the French used “every little rising – tree – Stump –Stone – and bush kept up a constant galding [sic] fire upon us.” By sunset on July 3rd, 1754, one-quarter of the British soldiers were killed or wounded. It was clear that the French were able to get close enough to deliver effective musket fire on their enemy.

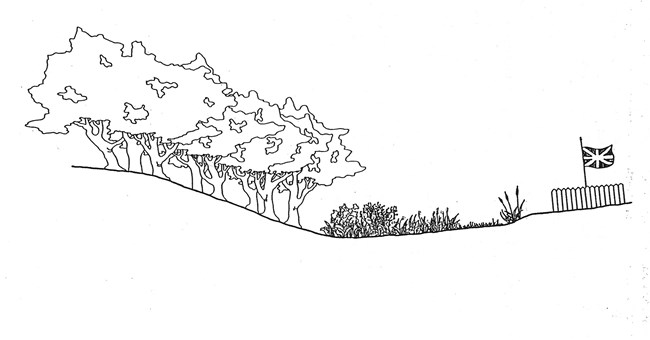

The fort was located in a level, grassy bottom known as the Great Meadows. An old growth forest bordered the meadows, with meandering streams that flowed through the center. Due to the high water table, the marshy low-land prevented trees from growing and filling in the meadow.

Over time settlement occurred and the landscape changed. The trees were cut and the stream was channelized. By the 1900s all evidence of the historic forest and meadow were gone. A postcard from 1904, (figure 1), shows the remains of Fort Necessity’s earthworks in the center as a white diamond. Though most of the scene shows fields and pastures, the historic meadows would have only taken up a small portion of the postcard’s view. The picture documents that the historic landscape had vanished.

In 1932, The U.S. Government established Fort Necessity National Battlefield Site. It included the two-acres around the remnants of the fort and was surrounded by a Pennsylvania state park over 300 acres in size. That same year the first reconstruction of the fort was built and the site was open as a tourist attraction. The landscape around the fort changed from farm fields to park-style mowed grass (figure 2).

In the 1980s, the management at Fort Necessity National Battlefield wanted to restore the historic landscape, in order to help the public understand the battle. The staff stopped mowing the grass outside of the immediate fort area and waited for the forest to grow. Unfortunately, the hillsides became covered in Japanese Honeysuckle, an invasive shrub. Aside from the invasion of the Japanese Honeysuckle, the meadow grew into a solid expanse of goldenrod, crowding out the native grasses that would have originally occupied the meadow.

It became clear that more aggressive intervention was needed to re-establish the forest/meadow interface.

Searching the Historical Record

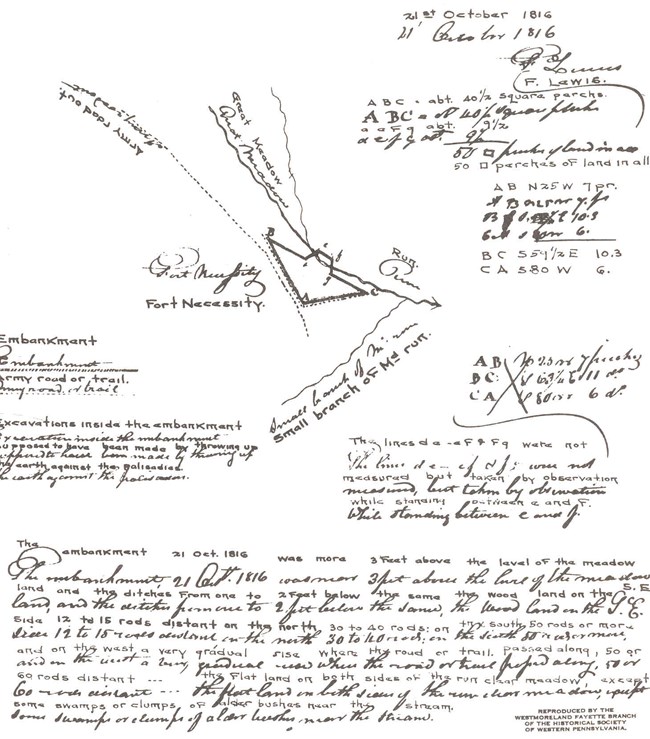

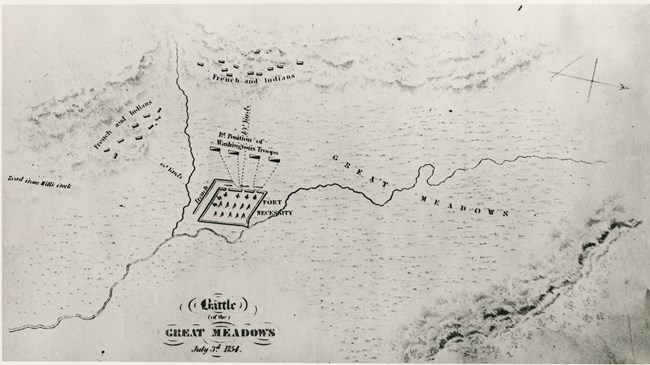

The historical accounts describing the battle at Fort Necessity agree that the French firing upon the fort from the woods. Unfortunately, none of the original authors gave a detailed description of the landscape, or recorded from which direction the French attacked. Likewise, there were no known maps of Fort Necessity from the time of the battle. However, important information might be gleaned from early maps of the battlefield.

On Oct 21, 1816, Freeman Lewis, a surveyor, was the first known person to map the remains of Fort Necessity. It was feasible that the meadow and the tree line had not changed significantly in the 62 years since the battle. He found the remnants of the fort clearly visible and reported the embankments were “3 feet above the level of the meadow and the ditches from one to 2 feet below.” His drawn map concentrated on the fort and did not show the trees (figure 3). However, he listed the distances saying, “The woodland on the SE side 12 to 15 rods distance [66-82 yards,] on the north 30 to 40 rods [165-220 yards,] on the south 50 rods or more [275 yards] and on the west …. 50 or 60 rods distance [275-330 yards].” It seemed obvious, since he uses such a wide range of figures, that either the distances were estimated or the tree line varied. Either way an accurate tree line could not be established.

Lewis also describes the landscape of the meadow saying, “the flat land on both sides of the run [is] clear meadow, except some swamps or clumps of alder bushes near the stream.”

Sparks wrote the fort was built “in a bottom or glade surrounded by hills. This bottom is entirely level and about two hundred and fifty yards wide where the fort was placed… Within this space there were no trees; but the ground was covered with a course kind of grass and short bushes.” He also noted, “the intrenchments [sic] are still distinctly visible.”

Although these maps gave the staff a general idea where the forest/meadow interface may have been, more information was needed.

The scientific field of palynology studies the pollen grains found in the soil. In the 1990s improved optics and computers allowed the field to advance rapidly. The staff at Fort Necessity began a study to see if they could identify the tree line using palynology.

A pilot project proved that historic pollen could be identified and a full scale study commenced.

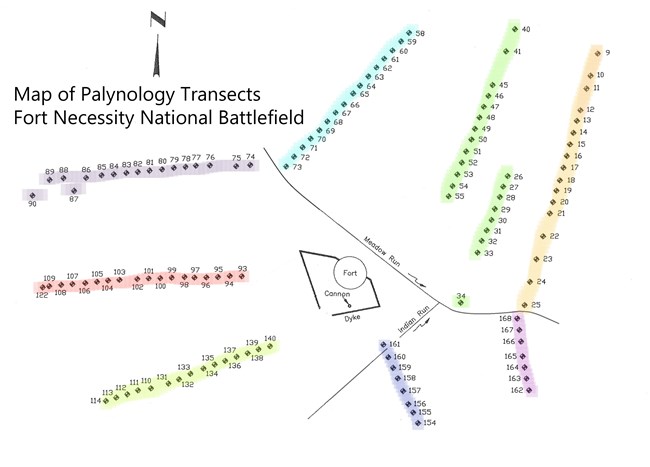

Eight transects were laid out, radiating out from the fort, with five on the south side of the stream and three on the north side (figure 5). Each transect had between seven and 18 cores. The study ended with just over 100 usable cores. Cores were generally located at 20 foot intervals along the transect. Each core was collected by hammering a 2” PVC pipe into the soil to a depth of 4.5 feet. The pipe was removed along with the soil it contained.

In the lab multiple samples were taken from each core, and the pollen was identified at 400x magnification. The top centimeters of the cores were dominated by grass pollen, indicating the mowed lawn grasses of the park landscape. The pollen from the middle of the core was dominated by ragweed, which is a plant adapted to living in North American cultivated fields. Ragweed and other weed pollen were indicative of the agricultural period. Tree and meadow plant pollen dominated the lower sections of the cores. This pollen was from before the forest was cleared and this was the pollen that was studied.

Although the pollen did drift, the author was able to determine where the amount of oak pollen from the dense forest decreased and the grass pollen from the meadow increased. This was where the primordial forest/meadow interface was located.This point was determined for each of the eight transects and historic tree line signs were erected at each of these locations.

The palynology report also gave the staff a clear picture of the type of trees and plants growing on the battlefield. The mature forest was dominated by oaks, with hickory and chestnut being the next most prominent trees. This data concurs with what historic travelers recorded. For instance, in 1784 George Washington wrote that the land in the mountains was “chiefly white oak. It also agrees with the native forest type scientist have attributed to this region, the Appalachian Oak forest. The pollen showed the dry meadow was dominated by plants such as ironweed and goldenrod. The wet meadow was mostly grass, with other plants such as sedges and cattails.

Using all this information the management at Fort Necessity was confident they could restore the historic landscape. In 2018 the remnants of an old parking lot were removed and replanted with grass. That same year 50 trees were planted along the historic tree line.

The signs and the newly planted trees help today’s visitors visualize the historic scene. Many more trees are needed to restore the view to that of the battle. It will take awhile for the oaks to grow and mature, but it is a start. In the future, visitors will be able to view a landscape that much more closely resembled the one George Washington saw during the battle in 1754.