The author of more than 100 scientific publications in the fields of paleobotany, forest history, restoration ecology, and environmental quality, Leopold pioneered the use of fossilized pollen and spores to understand how plants and ecosystems...

Article

Restoring the Balance

An Interview with Conservationist Estella Leopold

Estella B. Leopold is a botanist and a conservationist. She is a University of Washington professor emeritus of botany, forest resources, and Quaternary research, and has been teaching and conducting research for more than 60 years. The author of more than 100 scientific publications in the fields of paleobotany, forest history, restoration ecology, and environmental quality, Leopold pioneered the use of fossilized pollen and spores to understand how plants and ecosystems respond over eons to things like climate change.

Her work with the U.S. Geological Survey and at the University of Washington has aided our understanding of past vegetation and climate in Alaska, the Pacific Basin, and the Rocky Mountains. Leopold’s engagement as a conservationist includes protecting fossil locations in Colorado, fighting pollution, and protecting wildlands. She is the daughter of Aldo Leopold.

Leopold was born in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1927. She graduated with a degree in botany from the University of Wisconsin in 1948, attained her Master’s in Botany from the University of California at Berkeley in 1950, and completed a PhD in Botany from Yale University in 1955. At Yale, Leopold began to specialize in studying pollen on a dare from an advisor. Out of her PhD program, Leopold took a job with the U.S. Geological Survey. Her work studying drill cores containing pollen from the Miocene Epoch revealed evidence of a tropical rainforest sunken 1,500 feet below sea level under Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. By studying the Rocky Mountains and Alaska, Leopold helped recreate the temperate paleoenvironments of the Tertiary Period. Her research in Washington State revealed the role of Native Americans in shaping past fire regimes.

Her work at the Florissant Fossil Beds in Colorado made the case for the necessity of their preservation, an achievement which contributed to Leopold’s receipt of the prestigious International Cosmos Prize in 2010. The area was threatened by real estate development until she and several others filed suit. In 1969, the 6,000-acre Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument was established by Congress.

Other conservation actions taken by Leopold include opposing oil shale development in western Colorado, stopping dams from being built in the Grand Canyon, and ending the burial of high-level nuclear waste in eastern Washington. In 1969, Leopold received the Conservationist of the Year Award from the Colorado Wildlife Federation. She was elected as a member of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences in 1974, and two years later she was awarded the Keep Colorado Beautiful annual award.

NPS / Neal Herbert

Yellowstone Science (YS): I know quite a bit about your family just because I have read things that your father has written, and I’ve worked for the Park Service my whole life, so of course, your brother Starker is well known to me. But I was very interested in your career, and in particular I read in several places that even though conservation seemed to be sort of a predestination for a lot of people in your family, you stumbled into paleoecology, and I wondered how that happened, how it was that that became your primary focus.

Estella Leopold (EL): It was kind of a stumbling-in story. I was a new applicant at Yale University Graduate School, and my major professor was the great Paul Sears, and he was, of course, a palynologist. I told him I wanted to work in physiological ecology, with plants, and he said, “Fine, but why not palynology?” and I said, “Well, I don’t think you could answer a lot of ecological problems with fossil pollen.” He said, “You mean it can’t be done?” I said, “Well, it would take a lot of work.” Sears said: “Are you afraid of a challenge?” So I began to try some work on pollen from the river terraces where Luna Leopold was working out of Wyoming, and got started there. It was a lot of fun. And I finally realized, this is great stuff, so I did a PhD thesis on postglacial pollen in Connecticut. And I was recording some of the early forests following glacial retreat and climate change.

YS: Well, that’s a pretty timely topic for now. So your primary interest was in plant ecology. But also it seems to reveal a little bit about your character that you couldn’t resist a dare. So your PhD was at Yale, and then when you finished your graduate work at Yale, did you immediately go into teaching?

EL: Well, it turned out there was an opening in the U.S. Geological Survey in Denver. They were opening an interdisciplinary paleo lab with people working with different kinds of algae and snails, and they wanted a pollen analyst. And I was one of two candidates–I managed to get it. I was very happy.

YS: Well, I bet paly–how do you say that word again, paly...?

EL: Well, Paul Sears invented this word. He said, “How do we express in a word the study of pollen and looking to reconstruct vegetation of the past?” And he reached into the dictionary and came up with paly, P-A-L-Y, which is Greek for “flour.” And pollen is about flour-sized, so he said, “Let’s just call it palynology.”

YS: Yeah, I don’t think there are probably that many of you now, are there?

EL: Well, it’s still going strong in the United States. There’s a lot of work right now going on in climate change and with the postglacial/interglacials. So the work in the deeper time–there are fewer of us. It’s still pretty exciting.

YS: Has your field of study been a rewarding area of research in light of your conservation interests?

EL: That is an interesting question. One of the things that my Dad and Starker Leopold had in common was that they could integrate their work in wildlife research with their interest in conservation. And in pollen work, it was harder for me to find a way to use palynology as a tool in conservation. But now it appears that it’s a good tool because we can talk a lot about our current concern about climate change.

YS: Your research paints a broad picture of changing climates, mountain-building, and species evolution and extinction. What are your thoughts about the dominant drivers in shaping the Rocky Mountain ecosystem when you’re thinking about the distant geologic past?

EL: Of course, one of the drivers was topography. And in the ancient past, Rocky Mountain history goes back to the Eocene, a time when tropical forests still existed in Colorado and Wyoming, 40 million years ago. That’s the early part of the post-dinosaur interval. At this time the region was low lying, before serious Rocky Mountain uplift. We know that because some California-based conifers, like Sequoia and Monterey fir that depend on a moist coastal climate proliferated in Colorado and throughout the West. We know it too from most recent creative geological mapping. Back then, there were no Sierras or Rocky Mountains to block the westerlies –the flow of moist Pacific air into Colorado.

After the end of the Eocene, a huge volcanic field developed in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. I mean, these were some of the largest super volcanoes and craters in world history, called the La Garita Volcanic Field. This went on for several million years—and tons of volcanic dust cooled the region. But cooling was also brought on by sea currents around Antarctica. In Colorado we found pollen assemblages showing that a great cooling had occurred. And some of the air-borne pollen was actually charred, toasted by the heat of the volcanic ash. It was at that time that the regional climate changed from summer wet, lots of deciduous trees like walnut, hickory, elm, to summer-dry, lots of sagebrush and pine forest. This was actually the start of the modern Rocky Mountain climate and ecosystem.

Talk about mountains? Well then in the latest Miocene, about 10 million years ago, the Colorado Plateau began to rise—a time when the main Grand Canyon was carved. Much of the midcontinent area from New Mexico to Montana rose about 4,000 to 5,000 or more feet. Ta dah! We had Rocky Mountains! Well, it took a few million years. I might add that a famous Yellowstone geologist, J. David Love and I showed that the high Tetons next to Yellowstone are very young; they date back only 2 million years, at the beginning of the Ice Age.

YS: I’ve interviewed quite a few geologists, and they talk about time in a way that, for the normal person, is really hard to understand. We’re talking such huge amounts of time. But a lot of your conservation work seems to be applying things to a much shorter timeline. And I’m wondering how you make that transition?

EL: Maybe through an awareness of what we have today and how it’s being decimated by lumbering or mining processes, is pretty frightening. And it’s, if I must say, kind of a separate topic, isn’t it, from talking about how things were in Yellowstone Park in the Eocene.

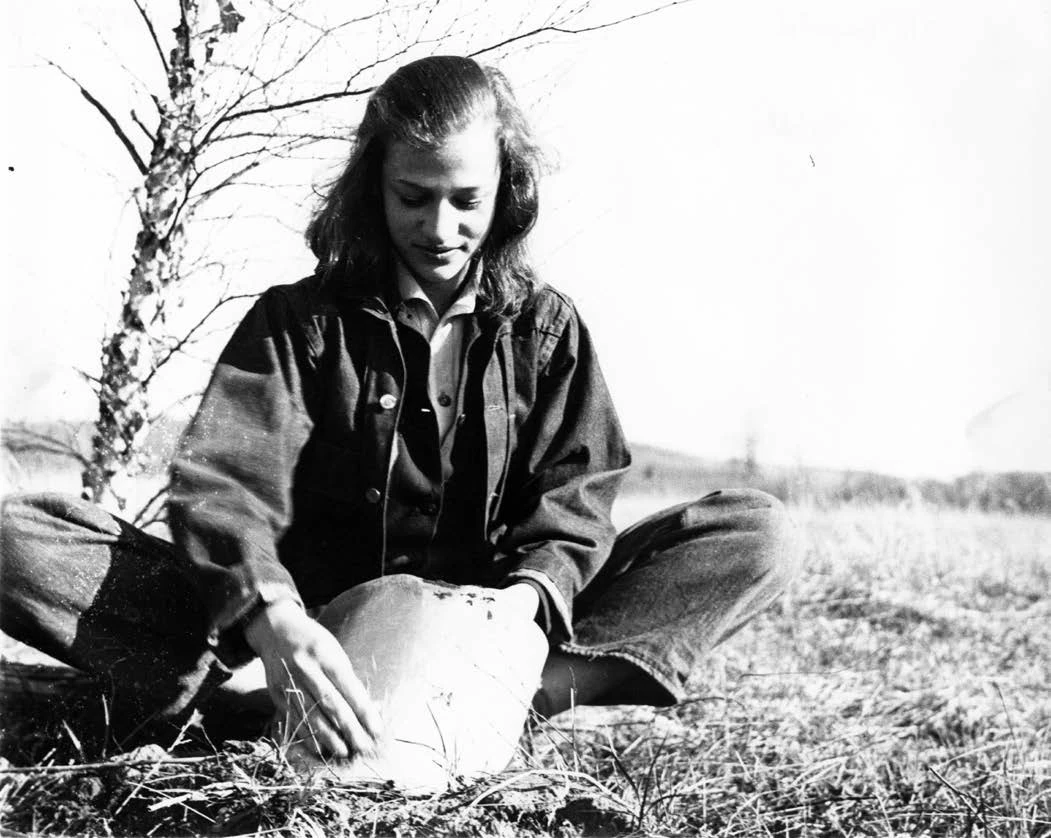

Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, www.aldoleopold.org

Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, www.aldoleopold.org

YS: Right. Well, you seem to make that transition a lot more smoothly than I can as a layperson. I mean, a lot of your academic work deals with the very, very distant past, but a lot of your recent writing is very contemporary, particularly in the climate change field, which is what a lot of these questions focus on.

EL: You can see, one of the things I’ve been interested in is the evolution of landscape, and that includes the fauna and the flora and the climate. So when you put all those together, you can summarize very nicely what’s happened in the last, say, 40 million years in Yellowstone, and that’s a fascinating story.

YS: I also read a little about your work with prehistoric fire, and that was interesting to me because that is a totally different kind of timescale than geology or paleontology. And one of the questions that was asked by one of our ecologists here is: Do you think the importance of deliberate burning by prehistoric peoples is beginning to get greater attention?

EL: Oh, yes, I think so, and of course, Starker, and a little bit Dad, started all this with their interest in the evolution of a theory on the natural role of fire in the west. The Southwest has a summer-dry climate, where periodic fire is a part of the system.

What Dad and Starker saw in Mexico in their trips to the Sierra Madre was an eye-opener. Looking at the landscape it was quite clear that people were burning regularly there and that it had a big impact on maintaining this particularly wonderful varied landscape. They came home from that trip with a completely new idea about natural fire in ecosystems. In California, Starker was looking around and was struck with how prevention of fire was creating great fire hazards with thick undergrowth. He said he began to wonder if this was the way to manage western forests.

So then when Starker had an opportunity to report to Secretary Udall about park management, he went for it, saying, “We really need to make decisions about management that includes natural fires.” And so, yes, I think that this is certainly catching on now. People are beginning to see, especially after the big Yellowstone fires, that this is a natural part of the landscape ecosystem and it’s good. The question is, what do we do with all the forests that we haven’t permitted to burn for 50 years? Which are very inflammable. So that’s the big management issue now for the Forest Service and perhaps for some of the parks.

YS: Did you in your work find evidence of these fires in the paleoecology record as well?

EL: Yes we have, but it isn’t really that long ago that the Sequoia/Kings Canyon area was described by John Muir as having regular summer ground fires. He used to be able to sit by the fire while it burned along under these huge Sequoias, and he thought that fire was a natural element in that country, because of its summer-dry climate. Then Starker got involved. Park rangers told Starker that Sequoias were not reproducing. He needed to know why. Once he got the ear of Udall, and the opportunity, he arranged with the scientists at Chico to experiment with fire in the Sequoia/Kings Canyon area. And by golly, they found that the reason Sequoias were not reproducing was the thick soil A-horizon, with all the needles and branches and stuff, where the tiny Sequoia seeds could not penetrate. But the white fir was doing fine, because it has big seeds that can grow down through all that duff into the mineral soil; therefore, fir was becoming an understory and was replacing baby Sequoias, there just weren’t any baby Sequoias. But once the Chico scientists started to burn, up came millions of baby sequoias. So this was a great, great feat, which Starker and then Bruce Kilgore wrote a lot about. The goal, as Starker said, is to follow what you construe to be a natural ecosystem. And you want to maintain the natural contributions of, say, fire to maintaining that system. That was a major accomplishment. Starker arranged for NPS to carry out thinning operations and then ran experimental burns upslope in Kings Canyon National Park. Very brave. These were remarkably successful. Apparently Sequoia stands need periodic ground fire.

YS: Many of the questions that I was given have to do with the Leopold Report, which of course is something that has really shaped the management of national parks for many years. Why do you think that’s had such an enormous impact?

EL: I think that Starker’s talks and publications were the first trigger that captured a lot of interest. You should know that there was a period when Starker gave early reports to the Sierra Club so that he could get their interest and support in these new ideas about the natural role of fire and management. The board of the Sierra Club was absolutely horrified that “a son of Aldo Leopold” was promoting the use of fire in park management! They gave him a really hard time. It definitely took a while! The Sierra Club eventually allowed him to publish an article about fire ecology in the Sierra Club magazine in 1957 or so. Yes, that took a while.

After his experiences in Mexico, the Sierra Madre, he began to write things like “Wilderness and Culture.” He laid it all out in terms of wilderness and parks. Because of 50 years of fire suppression, management of the ecosystem now requires new kinds of actions.

Well, then when he had the chance to talk about [these things] in the Leopold Report, he said something like, “I could say anything I wanted,” and he did, talking with his committee, and developing the various ideas which are so critical. But he laid the groundwork first, and I think then his committee and then Udall himself were very happy with his suggestions.

He certainly moved forward with that report. I think he was saying that he accepted the premises of that first World Conservation conference on national parks—it was in the 1960s—that active manipulation was probably needed to preserve ecosystems and parks. The parks had to be big enough to house the fauna. And then went on to say something like, “Well, we don’t have to manage areas of tundra or rainforest, but we do down here at mid-latitudes need to manage because most of these areas are under constant change. And when they get out of balance, well, we have to actively manipulate.”

YS: I guess you probably have seen the new report, the “Revisiting Leopold” report?

EL: Yes, of course, and I was delighted to read it. It was very complimentary to Starker. We should be happy with it because the report says that now we need to pay very serious attention to monitoring—to measure the effect of the fauna on the vegetation. Boy, I certainly agree with that!

YS: Was Starker a mentor for you?

EL: Oh, very much so. When I graduated from University of Wisconsin, it was the year Dad died, and I didn’t know what I was going to do… Then Starker said to Mother, “If you send Estella out here to Berkeley, I’m sure she can get into graduate school, and we’ll take care of her.” So I went there, and for two years he was just marvelous, helping me out, guiding my research, and just being a good brother.

YS: I am curious to know what you think the emerging challenges are ahead for places like Yellowstone and the national parks.

EL: It’s a loaded question. I’m sure that part of the challenge is the need for careful monitoring of the wildlife populations as well as the vegetation on which they depend. The parks management should use top flight ecologists for this monitoring job; they need to maintain the balance between the ungulates, the stream-side birds, the streams, the small mammals, the aspens and willows, and the obvious need for the top predator, the wolf. Those food chains need to be balanced, and not get out of whack as they did in the Lamar Valley in the 1980s and 90s. Instead of giving the wolf his role, we were killing thousands of elk and bison with paid staff. We were not paying attention to balance in the ecosystem, or we did not even see it.

The huge overpopulations of elk in the Lamar Valley were obviously damaging the entire ecosystem. The new “Revisiting Leopold” report sets rules and calls for detailed monitoring, so that we do not get these huge overpopulations. We very much need the wolf to maintain that balance.

YS: I know that climate change is a big topic for you, and one that certainly was covered heavily during the 11th Biennial Science Conference. What do you see the Park Service’s role in that particular issue being? Or do you have any thoughts on that?

EL: Yes, I have thoughts on it. I’m scared to death. It just seems to me it’s so daunting. If we have trouble managing Yellowstone and other Western parks under the present climate—which is tricky enough—just what do we do when the climate is changing? Some habitats are moving up slope, and the fauna shifts with it. Some habitats lower down may become desiccated, like winter range. What is most alarming to me was when I visited the National Academy computer models at the Aldo Leopold Nature Center in Monona, Wisconsin. The models based on the CO2 increase were trying to estimate what the temperatures will be across the United States in the future. It’s absolutely frightening. It appears that between now and 2030 we will probably lose our capacity to raise crops in the Great Plains because of drought. We would lose the corn belt.

So what will be happening in the western parks? I am sure it is an incredibly complicated issue. By monitoring what these climate sensitive organisms are doing, and what are the changes we observe, still we have to think what we can actually do to help. Establishing archipelagos of habitat is one possibility. These could help migrants move northward. The most important thing is to convince the Congress that we now need to really try and stop CO2 increases. Congress talks about it now, but I am not sure they will act in time.

YS: Do you have any advice for your students or young people that are going into this sort of a career, as far as how they may meld science and advocacy, in particular when it comes to climate change?

EL: I think they all need to be advocates. I think they need to be expressing themselves. I mean, that’s what is certainly needed. And a lot of folks are not doing it. It’s hard, especially when you realize what the young professors have to do. They have to bring money in for their students, they have to write papers...and grade papers and go to committee meetings. And it’s hard for them to find time to be an active political advocate, and yet, that’s what’s needed. We need more advocates, don’t we?

YS: I was just looking at the little list I have of things that you’ve worked on: oil shale development opposition in western Colorado; helping stop dams from being built in the Grand Canyon; helping stop the burial of high-level nuclear materials in eastern Washington. These projects that you’ve worked on, do they continue to be your passion, or do you have new ones you’re working on?

EL: At the Leopold Foundation in Wisconsin, our office is working hard on trying to extend and foster the extension of my dad’s Land Ethic. We’ve been holding workshops across the United States with the aim of developing land ethic leaders—ambassadors—among the different age groups, encouraging nonprofit groups to focus on selling these ideas. We are holding one in Seattle in September, 2014. Part of our focus is on teachers.

I think that climate change is an issue that we really need to jump into as scientists. We need to be talking to our brethren about it. There is to be a large gathering, a hearing, in about a week at the Convention Center, because it’s the biggest building in downtown Seattle, about the coal trains bringing coal from Wyoming to ship it off to China. We are all very eager to fight this because it’s just going to ruin the coastal area of Washington. These trains will be two miles long, and there’ll be dust. Possible spills. Why are we doing this? Several of my friends are going–they’re really important administrators, and mothers, and all kinds of people. We are all going down there to stand up and testify that we that we need to stop this, opening up our ports on the West Coast for coal shipments to China. That is one aspect of climate change we could avoid. I think it’s really neat that we can get some of our administrators pretty interested in it. I mean, our senators are. They’re hearing from us.

YS: You obviously have this huge timeline with your scientific work, and then you have projects that are going on now. What kind of things do you still feel like you want to accomplish? What kind of dreams do you still have about your work and the advocacy efforts that you’re making?

EL: That’s a good question. With the time I’ve got left, one of my big concerns is to straighten up my fossil collections so that I can leave some to the Burke Museum in good order, and return some to the U.S. Geological Survey in Denver. That takes a lot of work. I have two young people in the lab helping me with this. I will let my guard down on high-level activism, but I think working towards awareness of climate change and its impacts is something I’ll continue to spend time on. Climate has always been a driving force, hasn’t it? It can change our world.

YS: It was lovely to talk to you. I consider it an honor.

EL: My pleasure indeed.

The Leopold Lecture

A Legacy of Ecosystem-Scale Thinking

The “Leopold Lecture” is a centerpiece keynote at the Biennial Scientific Conferences. Past speakers have included Richard Leakey, African paleontologist and conservationist. Speakers usually address important science and management questions on the larger scale of ecosystems and nations. Named for A. Starker Leopold (1913-1983), an ecologist, conservationist, and educator, as well as a primary force in the shaping of modern National Park Service policy, this lecture highlights critical work in the field of conservation biology. As a scientist, Leopold produced more than 100 papers and five books, including classic studies of the wildlife of Mexico and Alaska. As a teacher, he inspired generations of students in numerous ecological disciplines. As an adviser to several Secretaries of the Interior, Directors of the National Park Service, and as chairman of an Advisory Board on Wildlife Management in 1963, Starker led the parks into an era of greater concern for scientifically-based management decisions and a greater respect for the ecological processes that create and influence wildlands. Starker was the oldest son of Aldo and Estella Bergere Leopold, and brother to Estella.

Tags

- yellowstone national park

- yellowstone

- yellowstone center for resources

- yellowstone science

- ys-22-1

- conservation

- estella leopold

- starker leopold

- aldo leopold

- botany

- quaternary research

- paleobotany

- forest history

- restoration ecology

- environmental quality

- climate change

- fossilized pollen

- u.s. geological survey

- university of washington

- alaska

- pacific basin

- rocky mountains

- florissant fossil beds national monument

- conservationist of the year award

- colorado wildlife federation

- national academy of sciences

- yale university

- wildfire

- j. david love

- stewart udall

- sequoia kings canyon national parks

- sierra club

- leopold report

- revisiting leopold report

- 11th biennial scientific conference

- leopold nature center

- miocene

- richard leakey

- colorado

- women

- ak1

Last updated: April 21, 2025