Last updated: February 3, 2020

Article

Researchers Look to Better Understand and Explain Blob-related Common Murre Die-off

Piatt JF, Parrish JK, Renner HM, et al. (2020) Extreme mortality and reproductive failure of common murres resulting from the northeast Pacific marine heatwave of 2014-2016. PLoS ONE 15(1): e0226087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226087

January 2020 - The most powerful marine heatwave on record, known as “the Blob,” wrought a lot of havoc from 2014 to 2016, from harmful algae blooms to baleen whale die-offs. A recent study focuses specifically on how it impacted common murres. Common murres are dominant, fish-eating seabirds in the northeast Pacific, capable of flying faster than any other northern seabird and diving to depths of more than 150 feet in search of prey. Occasionally, they suffer die-offs, but none compare to the die-off that occurred during the Blob. The researchers estimate that while around 62,000 murres washed ashore dead or dying from California north to the Gulf of Alaska, as many as 1 million birds likely perished. Most were adults, and the die-offs were accompanied by at least 22 complete breeding failures throughout the region. The proximate cause was starvation, but the researchers wanted to know more. How, precisely, did the Blob cause these birds to starve?

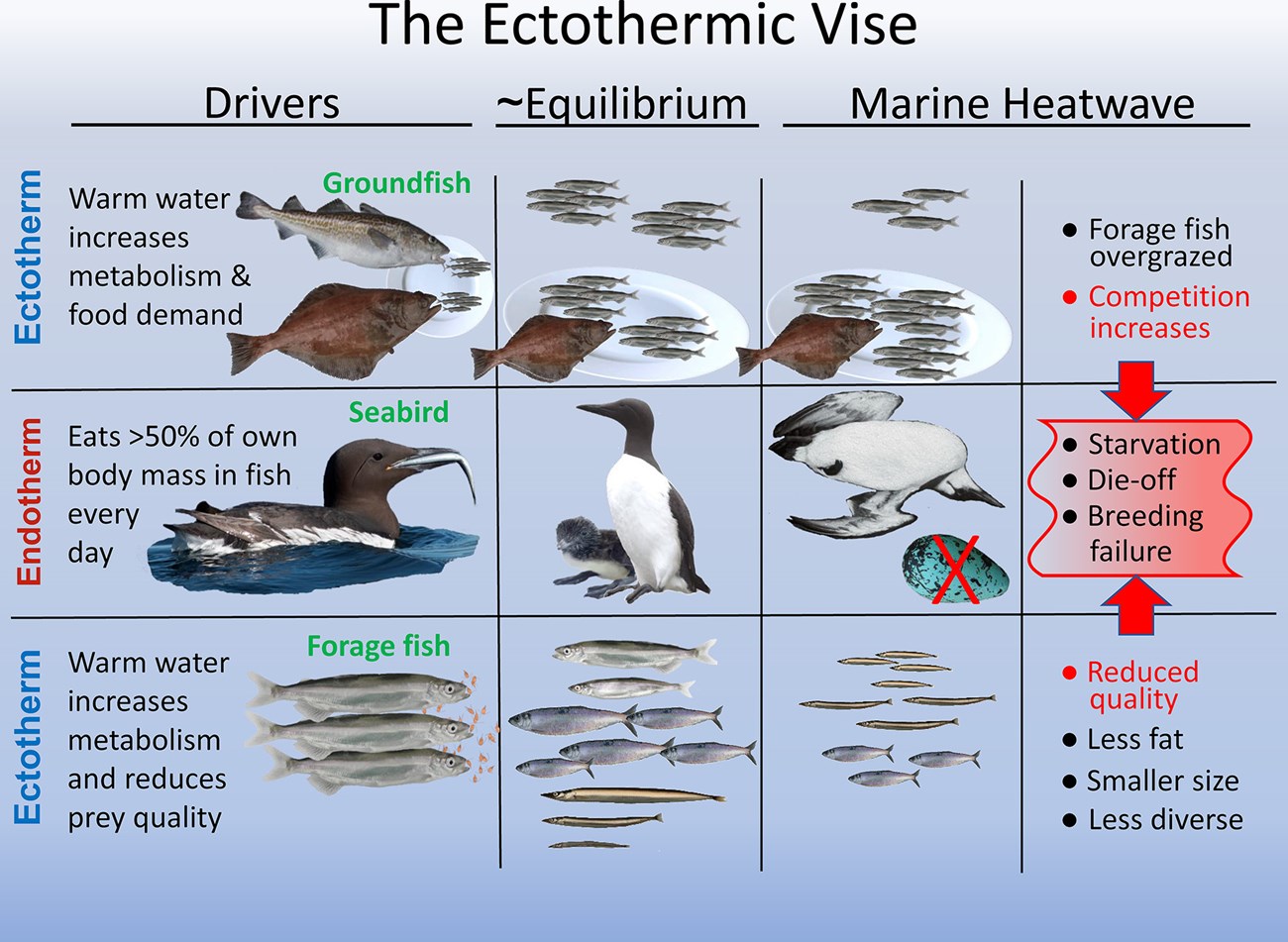

Examining the birds’ ecology and that of their prey base, the researchers came up with a hypothesis to explain the common murre die off. They call it the “ectothermic vise” hypothesis. Ectotherms are creatures that don’t need to control their body temperatures. Some groups of ectothermic fish are common murre prey species, while others are murre competitors. Other studies have shown that fish metabolism increases in warmer conditions, increasing their need for food, and that warmer conditions reduce the amount of food available for the smaller fish species. Thus those smaller common murre fish prey species may have been starving themselves during the heatwave. And the murre’s fish competitors, also hungrier, would be trying to eat more of those smaller prey species themselves. In other words, a marine heatwave might cause there to be both less prey and more competition for common morres. Since murres are endothermic, or warm-blooded, they need significantly more food to survive than their ectothermic competitors, and can starve within just a few days if they can’t find it.

Check out the full article published in PLOS ONE for more on the researchers’ findings and hypotheses.